The global hunt to unlock the healing powers of … poop

Scientists have discovered that gut-born bacteria may hold the secret for treatments of everything from IBD to Parkinson’s disease. Now they just need samples from the people living in the most isolated, nonindustrialized places on Earth. It’s a messy process, for many reasons.

The first Bajau volunteers pulled up in canoes around 11 a.m. and gathered on a rickety wooden balcony surrounded by the turquoise expanse of the Sulu Sea. They were the intrepid ones. Over the previous week, word had spread through the settlement of roughly 200 adults and children living in houseboats and wooden huts perched above the ocean just off Mabul, a tiny island northeast of Borneo: A team of outsiders was coming to visit with an unusual offer.

For centuries, the Bajau Laut, a mostly stateless Indigenous group sometimes referred to as sea nomads, had lived an itinerant life on the water, hunting tuna with spears, diving for spider conchs, abalone, and sea cucumbers, and dusting their faces with cooling powders made from rice and pandan leaves. In recent years, they had drawn the interest of scientists for their exceptionally large spleens, which allowed them to hold their breath underwater for as long as 13 minutes, a unique adaptation to the abundant ocean ecosystem that had sustained them for generations.

But the research team that arrived this past October from Germany’s Kiel University and Malaysia’s Universiti Malaya had come to gather information about an entirely different kind of ecosystem. They were there to learn about the vast community of unseen organisms living on the skin and inside the digestive tracts of the Bajau themselves. The team would compensate volunteers for their time—but, as a translator conveyed to the roughly 20 villagers gathered on the balcony that morning, that offer came with an unconventional request: The researchers had come to collect feces, and they’d take as much of it as each volunteer could muster. Plastic bowls would be handed out shortly.

The request was met with giggles and jokes that belied the stakes of the mission. Scientists finally have the tools to study the trillions of invisible organisms that reside within us—the microscopic world known collectively as the microbiome. And in recent years they’ve made some alarming discoveries. The industrialized world has reshaped the human microbiome to be far less diverse and resilient than that found in the guts of individuals living more traditional lifestyles, like the Bajau people.

That insight, along with a growing number of studies suggesting changes in the composition of the gut microbiome often accompany many chronic maladies, has raised a series of urgent questions.

“The question is whether the diseases that we have now that are skyrocketing in prevalence—like obesity, like diabetes, like liver disease, some forms of cancer, even some neurological diseases like multiple sclerosis and Parkinson’s—are in part due to deficiencies of microbes that we can resupply,” says Rob Knight, a computational microbiologist and microbiome pioneer who directs the Center for Microbiome Innovation at the University of California, San Diego.

That last part—resupplying—is critical. If remote cultures across the globe have stronger, healthier, more diverse microbiomes, could they help us cure diseases? Would collecting, and then using, their microbes even work? And what are the ethics of taking someone’s poop, even if the intentions are good?

Eager to answer those questions (and more like them) is the Global Microbiome Conservancy (GMbC), an international consortium of scientists building a biobank of fecal samples from the world’s most remote populations and a library comprised of tens of thousands of individual bacterial strains derived from each stool specimen. The GMbC has been at it for almost a decade, collecting gut bacterial samples from nonindustrialized populations in Europe, America, Africa, and Asia—from Tanzanian tribespeople to Inuit in the Arctic Circle—while hoping to document the evolution of human microbiomes across the globe. In the process, it aims to better understand the impact of industrialization, processed diets, and antibiotic use on human health.

The stakes couldn’t be higher. Globally, more than 10 million people suffer from inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), chronic inflammation in the gut that manifests as ulcerative colitis or Crohn’s disease. In recent years, evidence linking the onset of those two conditions to abnormalities in the gut microbiome has steadily grown. Differences in gut microbiome composition have also been found in those suffering from a wide array of other conditions, from autism and type 2 diabetes to heart failure, cancer, anxiety, arthritis, and more. Long believed to be expendable microbial hitchhikers picked up at random, much of the bacteria living inside us, particularly our guts, are now understood to be critical players in the complex, holistic systems that govern human health. Many coevolved with us over millions of years and operate like microscopic chemical factories essential for healthy development and the efficient functioning of the human body. And yet, there’s still so much to learn, including one key mystery: whether or not microbial changes are the cause—or the result—of a wide array of connected diseases.

The possibilities that could be unlocked by the GMbC’s work are tantalizing. But first, it needs to find more poop.

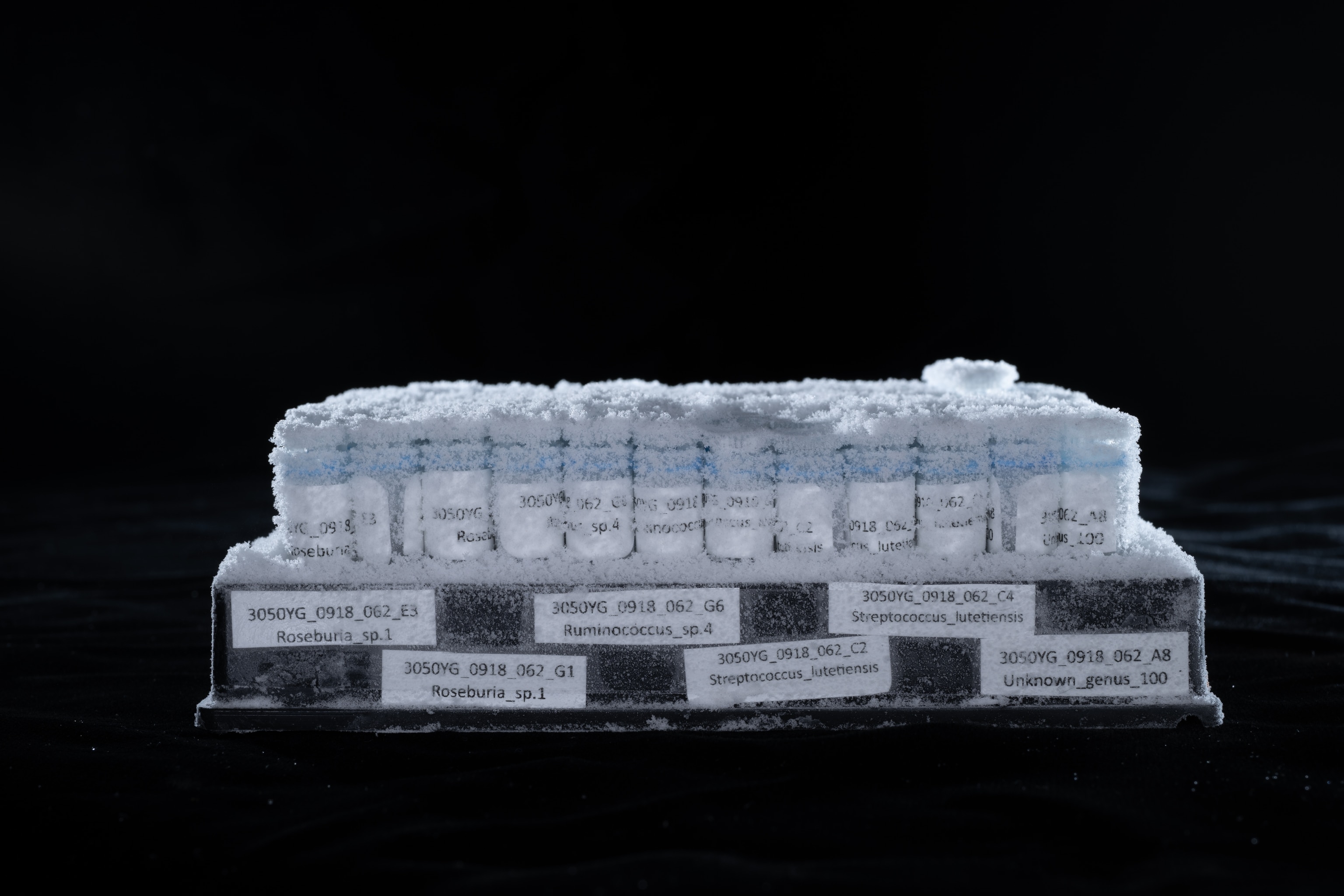

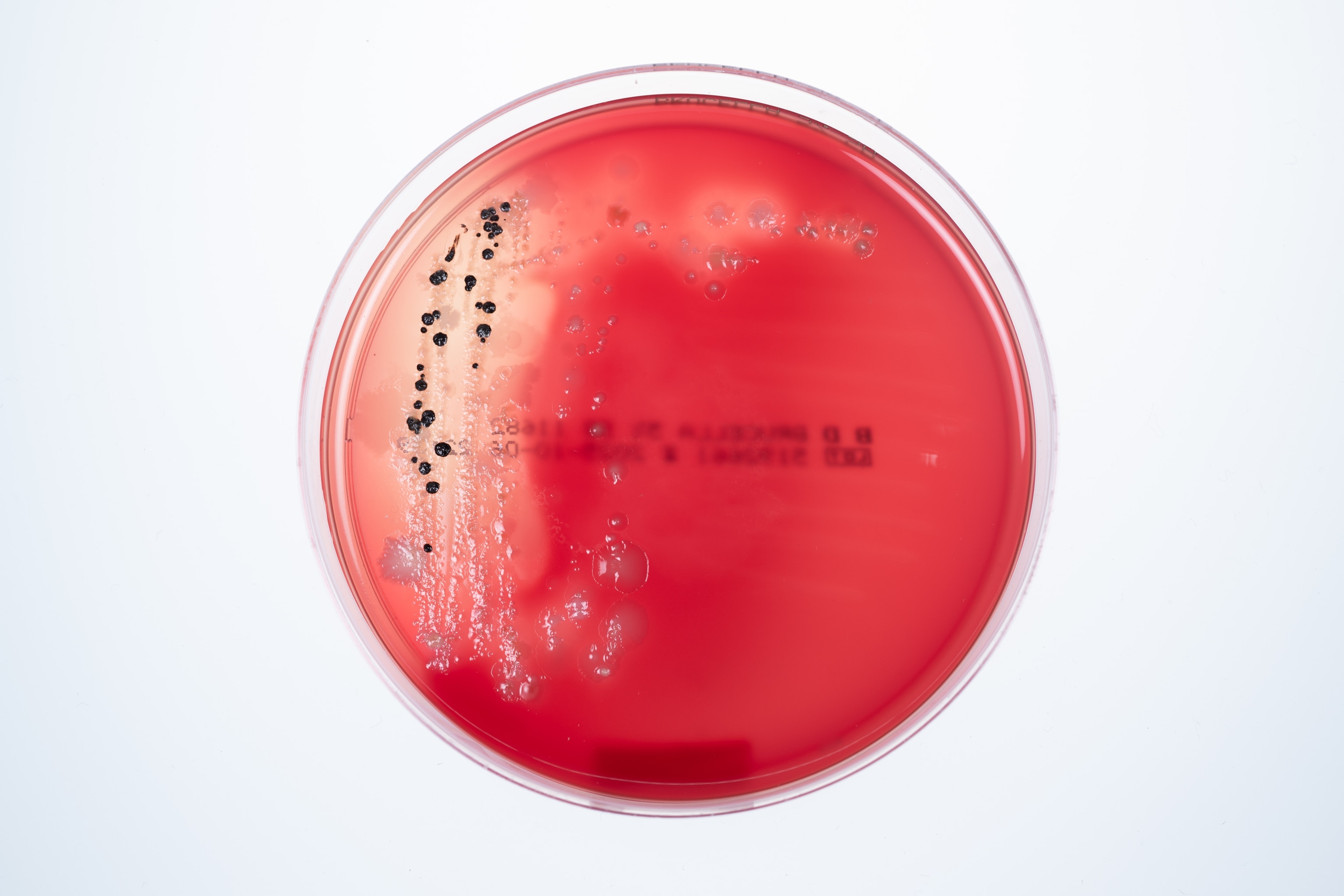

The GMbC’s growing fecal archive, housed in a series of freezers in the recently established Kiel Microbiome Center in Germany, currently contains close to 2,000 stool samples from some 50 human communities worldwide, ranging from urban centers in industrialized countries to remote villages. Each stool sample has been genetically sequenced, revealing the presence of thousands of bacterial species never before seen, studied, or named. From this biobank, nearly 10,000 bacterial strains representing roughly 600 species groups have been cultured, isolated, sequenced, and made available to scientists around the world.

Overseeing this burgeoning Alexandria Library of poop are Mathieu Groussin and Mathilde Poyet, the French husband-and-wife team who first conceived of the GMbC. Their goal is to increase inclusion of underrepresented human populations in microbiome science and to characterize the full biodiversity of the human gut microbiome as it exists across the globe.

Groussin and Poyet were still postdocs at MIT when they first got the idea to create the GMbC, after reading a high-profile 2014 scientific paper that detailed the lifestyle, diet, and microbiome of a remote tribe of Tanzanian hunter-gatherers known as the Hadza.

The Hadza were living a lifestyle similar to that of early humans—who lived at a time when, presumably, evolutionary forces shaping the human microbiome were strongest. To collect the fecal samples, a team led by researchers from the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, Germany, traveled to the shores of Lake Eyasi in northern Tanzania’s Rift Valley.

The 27 Hadza tribespeople who provided fecal samples had little exposure to modern antibiotics and soaps and lived on a diet of honey, berries, baobab fruit, tubers, antelope, monkeys, bushpigs, baboons, and any number of other targets of opportunity that could be foraged, scavenged, or hunted. As a reference, the researchers also surveyed the microbiomes of 16 Italians living in Bologna, along with samples from rural farming groups in Burkina Faso and Malawi.

The differences between their microbiomes were stark. The Hadza had far higher levels of microbial richness and biodiversity than both the Italian urban control group and the African farm dwellers. In comparison, the Western microbiome looked as depleted and diseased as that of an IBD patient. A difference, the researchers suggested, with potentially dire consequences for anyone living in a more modernized world.

Humans and their microbes have evolved in tandem over millions of years, with microbes influencing everything from digestion to our personalities. One microbe found in Japan allows its human host to extract complex carbohydrates from seaweed. Another found in Africa helps people access energy-providing compounds from tough, fibrous tubers. Some microbes send signals that can speed up or slow down metabolism. Others produce essential vitamins, influence appetite, regulate blood sugar, and help train and support our immune system. Newer evidence suggests our microbiomes can even alter our brains, promoting extroversion, influencing mood, and determining how we respond to stress.

But the widespread use of antibiotics and antimicrobial soaps, along with changes to our diet, has eliminated many of our allies. The loss of microbial diversity, the Max Planck researchers suggested, has “had a drastic effect on health and immune function of modern Westernized human groups.”

Groussin and Poyet were uniquely qualified to dig deeper into the focus of the paper. Groussin, a computational biologist, specialized in genomics and evolution. Poyet, an expert in experimental microbiology and ecology, focused on more practical matters. She had built one of the world’s first microbiome biobanks from 11 healthy fecal microbiota transplant donors, to treat people in hospitals suffering from Clostridium difficile infections.

But to tackle the questions raised by the Hadza research, they’d need more data. Specifically, a lot more poop, from a lot more places. They pitched their mentor Eric Alm, MIT professor of biological engineering, on the idea in 2016, and he agreed to provide the funding. The Global Microbiome Conservancy was official.

A few months later, Poyet and Groussin boarded a plane headed for Yaoundé, Cameroon. They visited rural villages without electricity and documented the daily struggles locals faced finding sources of healthy food. It was an abrupt and sobering introduction to reality for the two French scientists, who’d rarely ventured outside the lab. In the months that followed, they climbed the mountains of Nepal to get samples from Himalaya villagers, distributed those telltale plastic bowls to Inuit communities in the Arctic Circle, and trekked deep into the jungles of northern Thailand to collect poop from remote hill tribes.

They encountered soldiers manning machine guns mounted on pickup trucks in the Central African Republic and dangerous elephants in Tanzania. They gingerly removed a poisonous scorpion when it jumped onto Groussin’s shirt. A massive snake consumed several chickens outside their tent. In Rwanda, their presence attracted a crowd of curious locals that grew so large, the researchers’ security team peeled out while Poyet was still sitting in the back of their vehicle, attempting to process the fecal samples they’d just received. She held on tight and tried not to spill the stool soup all over herself. Slowly, the GMbC’s collection grew. Today, in every country Groussin and Poyet visit, they sample both rural and city dwellers to capture the influence of industrialization in each region. Already, they have identified some promising, potentially transformative, microbes.

Among nonindustrialized communities, Poyet has isolated one microbe capable of transforming cholesterol into coprostanol, a metabolite the body harmlessly excretes in stool. In some of the communities where the microbe is found in high concentrations—like the Hadza—cardiovascular disease barely exists.

Because the GMbC’s library is available to the scientific community, collaborators are using its vast collection of samples to drive further discoveries. For example, previous studies have shown that children who meet the clinical definition for obesity often have different microbiomes. But it’s unclear whether the differences in their microbiomes are a cause of the obesity, or if the changes come afterward. To find out, Yanjia Jason Zhang, a pediatric gastroenterologist at Boston Children’s Hospital, obtained stool samples from 200 children in Washington, D.C., none of whom were classified as obese. He looked for a risk factor strongly associated with the later onset of obesity, zeroing in on those who had reported episodes of what’s known as loss of control eating. Genetic sequencing of their microbiomes revealed they had deficiencies in a single key microbe—which Zhang then pulled from the GMbC’s strain library and grew into colonies in the lab to study. The missing microbe, he discovered and will soon publish, was excreting a lipid previous studies suggested could stimulate GLP-1 cells in mice, lowering their blood sugar and promoting a feeling of satiety. Think Ozempic, but all-natural.

These findings have profound implications for the treatment of diseases—potentially saving lives in the microbiome-depleted West and the rest of the world. The path forward, though, is anything but clear.

Poyet’s discovery of a cholesterol-reducing microbe and Zhang’s isolation of bacteria that may protect against obesity suggest an obvious next step: introducing those microbes, or combinations of beneficial microbes, into the guts of anyone who might benefit. Or, as UC San Diego’s Knight suggests, treating any number of diseases by resupplying microbes that we have somehow lost, possibly improving our industrialized and beleaguered microbiomes into healthier, more resilient states.

That’s where the artificial human guts come in.

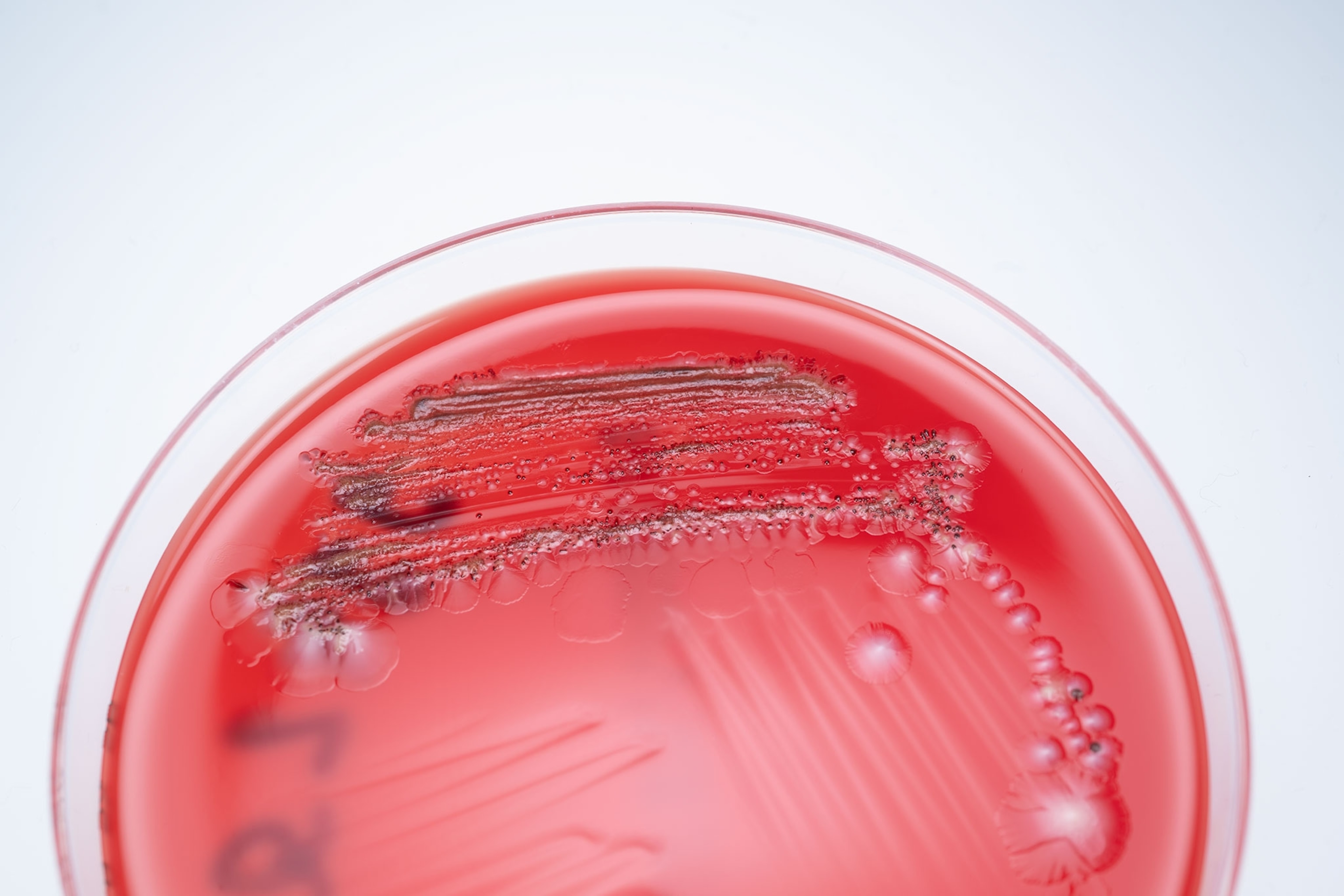

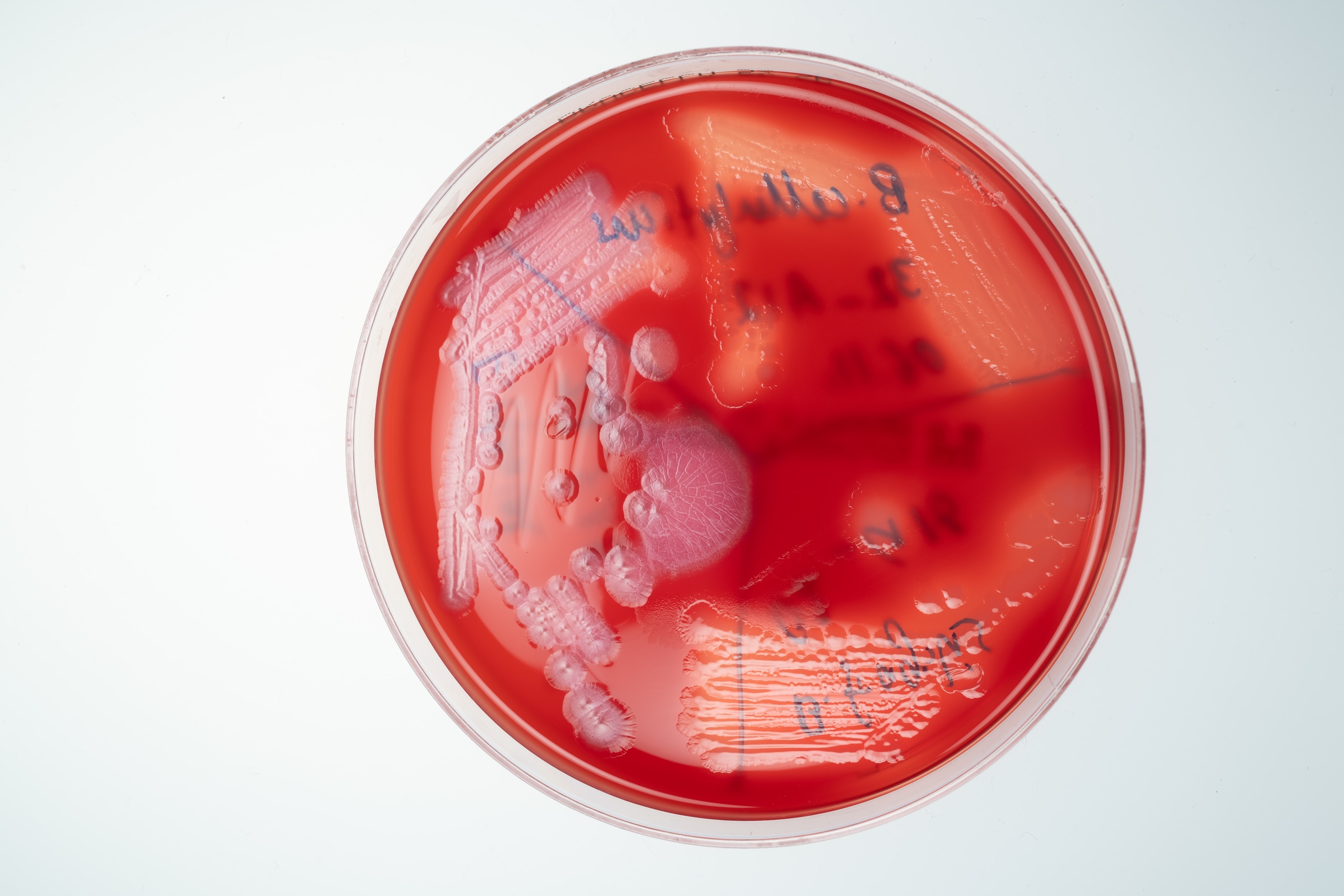

One warm morning last fall, Poyet headed down a long corridor in the Kiel University life sciences building, where the GMbC’s collection resides. She had moved there from MIT in 2023. Poyet strode into a fluorescent-lit wet lab with graduate students hunched over dishes. She stopped in front of two Rube Goldberg-like contraptions, each consisting of a large white console with a monitor above a pair of clear cylindrical glass containers buried beneath a jumble of white plastic tubing.

“Here,” she announced, “we have a bioreactor that is actually set up to mimic the human gut.”

In each of the lab’s four artificial human guts, Poyet can manipulate the environment to imitate the dynamic mix of gases, nutrients, liquids, and microbial composition present in a real human colon. The jumble of tubing allows Poyet to deliver a continuous flow of new nutrients—and for the artificial guts to “excrete” waste at a pace representative of real-world conditions. In the process, she can perform a wide array of experiments on individual microbiomes.

In one experiment, she re-created the gut of an IBD patient by seeding one of the glass receptacles with a bacterial community grown from stool samples provided by IBD patients treated at a local gastroenterology clinic. In the other three artificial guts, she used microbiomes derived from healthy individuals living in various stages of industrialization. Then she introduced oxygen into the normally anaerobic gut environment, followed by hydrogen peroxide, which is often released by colon cells in response to stress. Both gases are elevated in the guts of IBD patients and believed to drive chronic inflammation.

In all four artificial guts, the compounds caused damage. But the more diverse microbiomes collected from nonindustrialized communities returned to normal faster than those from more developed settings. The IBD patients’ microbiome recovery was the most sluggish of all.

How best to resupply the diseased microbiome in that glass container to improve its resilience is a conundrum that hangs over the heads of everyone in the field. Much of the basic science needed to understand the process by which individual microbes are able to successfully engraft in the human gut remains to be worked out. MIT’s Alm, for one, cautions that the ability to develop effective new drugs won’t be immediate. We’re far from simply swallowing a microbe-laced pill and fixing our industrialized, depleted systems.

“There’s this idea of, we want to make these as drugs and just take a probiotic, and it’s going to be the same as taking a regular small molecule drug,” says Alm. “But nobody’s done that. There’s just a lot of basic research that people need to do before they try to make a drug to cure a disease.”

It’s a lesson that Alm has learned through experience. In 2021 Finch Therapeutics, a microbiome start-up he helped found, went public and raised $128 million to fund a clinical trial for a therapy designed to treat C. diff, a deadly, opportunistic bacterial infection. Finch also set to work developing treatments for ulcerative colitis, Crohn’s disease, and autism spectrum disorder. Two years later, Finch discontinued Phase III trials and laid off 95 percent of its staff.

Finch’s failure was due, in part, to difficult biotech market conditions and the monumental costs of clinical trials. Alm suggests it was also brought down by a long list of unanswered questions surrounding appropriate dosing, which markers could be used to show therapies work in trials, and questions about how the resulting product might be manufactured. But there were also gaps in the foundational science, including an incomplete understanding of which nutrients and microbial neighbors might increase the chances of success for patients.

Research has made clear that the microbial context of any given microbiome can vary widely across populations and individuals depending on lifestyle, environment, and a wide array of other factors, notes Groussin. Microbe applications are not one-size-fits-all, in the same way that human microbiomes are products of myriad factors, from genetics to culture to location. And that context can have a profound effect on the way any one person’s microbiome and any specific microbe—particularly a newly introduced microbe—might interact. To better understand this context, Groussin and Poyet have been methodically screening each sample for markers associated with inflammation, which seems to be elevated in industrialized populations. They’re studying how microbiomes of nonindustrialized individuals transform when exposed to modern foods or medicines. And the GMbC maintains an active laboratory research program aimed at characterizing how different microbiomes behave under different conditions, including the introduction of new microbes.

Where Finch Therapeutics didn’t succeed Groussin and Poyet may yet make a critical breakthrough—one that unlocks the seemingly undeniable potential for life-improving, and possibly lifesaving, microbe-based therapies able to treat anything from Crohn’s to cardiovascular disease.

Of course, that would mean utilizing the microbes that the GMbC has collected from nonindustrialized peoples across the globe. And that puts Groussin and Poyet’s work in, well, a somewhat messy position.

One of science’s most glaring examples of exploitation was laid out in the best-selling 2010 book The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks, which told the story of how a Black woman—Lacks—had her cancer cells, taken during a biopsy in 1951, become the basis for decades of research and development for everything from mapping the human genome to developing polio and COVID-19 vaccines. Only in 2013, after years of legal battles, was her family granted control of the data stemming from her cells. In recent years, ethicists, scientists, and Indigenous groups have been engaged in a robust debate about how best to ensure the subjects of microbiome studies aren’t taken advantage of in the same way—and that fecal sampling isn’t just the latest chapter in a long history of medical exploitation. Many argue that Indigenous groups handing over samples deserve a say in research decisions, rights to their own data, and financial benefits that might come from the samples’ use. It’s a nuanced quandary that the GMbC finds itself navigating amid all the work it’s conducting on the ground and in the lab.

The issue was thrust into the spotlight in 2014, when an archaeology writer and Ph.D. candidate named Jeff Leach famously traveled to Tanzania, gave himself a rudimentary fecal transplant using a turkey baster filled with feces collected from the Hadza into his rectum, and posted about it on his blog. It gained momentum four years later, when Martin Blaser, a professor of the human microbiome at Rutgers University, argued in the journal Cell that humans should consider “rewilding” their microbiomes. Shortly after that, he and colleagues announced the formation of the Microbiota Vault, with a mission that sounds similar to the GMbC. Billed as a “Noah’s ark of beneficial germs,” the vault asks local researchers to share their collected fecal samples from communities that have been less exposed to antibiotics, processed diets, and bacteria-destroying soaps so that it can warehouse copies of the samples in a central repository.

Critics of the Microbiota Vault’s process argue that there is no mechanism in place to ensure donors benefit from research derived from the data.

Maria Gloria Dominguez-Bello, a Rutgers microbiologist and director of the vault (as well as Blaser’s wife), believes the critiques stem from a misunderstanding. She says that only donors who have provided a sample to the vault will have access to it, and they must give consent before their samples are sequenced and uploaded to an open-access database. Moreover, the Microbiota Vault—still in its early phases—has not yet stored any samples from Indigenous peoples (though it has 1,200 samples from urban populations) and won’t until it irons out the ethical issues.

The GMbC, for its part, says it will only provide access to its samples to noncommercial entities and only for research purposes—and that ownership of the samples and the microbes continues to reside with the donors. In addition, both Groussin and Poyet have insisted from the start that neither they nor their umbrella institutions—first MIT, now Kiel—will file patents for discoveries or claim ownership of the samples.

“The ownership of samples is left at the level of participants,” Groussin says. In short, the Hadza, the Bajau, and every other group who has contributed to the GMbC’s growing archive of poop remain the owners of all their unique gut organisms—not the scientists nor anyone else. (The GMbC says it only shares samples with scientists who forsake the right to patent any derivatives.)

Even so, some suggest their protections do not go far enough. Matthew Anderson, an associate professor in genetics at the University of Wisconsin–Madison of Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians descent, argues that both individual donors and their communities should be consulted each time their fecal sample is used for a new research project. (In 2023, Anderson published a framework spelling out how such a process would work, which he uses in his own microbiome research.)

Or, as National Geographic Explorer Keolu Fox, a genome scientist and associate professor at UC San Diego, puts it: “You can’t just be bioprospecting on people’s doo-doo,” he says. “Data is a resource.”

What is increasingly clear: Poop is powerful, and when it comes to microbiome medicine, feces—at least, the information inside it—is the future. Just as the rainforests of the world have yielded a voluminous list of medicines derived from plants and exotic animal toxins, the unexplored ecology of the gut microbiome seems certain to contain new compounds with powerful biochemical properties.

And much like efforts to protect those rainforests, the valuable debate over how to conduct fecal research is colliding with the urgency to act quickly. As globalization continues its relentless expansion into the farthest corners of the planet, traditional lifestyles like those of the Bajau are disappearing—and, along with them, untold thousands of microbial species whose importance to human health and well-being scientists are only beginning to understand.

“We’re just starting,” says Groussin. “We will find something.”