What was the Scopes Trial? How one teacher’s arrest sparked a national debate

In 1925, a small-town trial became a national spectacle, pitting faith against science. Here's what to know about the lasting legacy of the Scopes 'Monkey' Trial.

Was Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution scientific fact or dangerous, anti-Christian heresy? In 1925, one young teacher became a target of a law outlawing teaching evolution in schools—and a central figure in the fight to teach evidence-based science.

Twenty-four-year-old John T. Scopes didn’t remember if he’d actually taught evolution to his high school students in Rhea County, Tennessee—which would have been a violation of a 1925 Tennessee law. But that hadn’t kept him from volunteering to be accused of and ultimately arrested for it.

Remembered today as the stuff of legal legend, the so-called Scopes “Monkey” Trial pitted the scientific belief in evolution against Protestants’ belief that Earth and humanity were created by God—and raised questions about educational freedom, scientific inquiry, and evidence-based science that still resonate today. Here’s what to know about the explosive trial and its legacy.

How a Tennessee law strikes a national debate

Tennessee was just one of several states that tried to ban evolution from school curriculums during the 1920s. They were encouraged by a national anti-evolution movement that had gained steam in previous decades.

Religious resistance to science had risen as an avalanche of new discoveries in the 18th and 19th centuries threatened the authority of American Protestants. Many in the church questioned the new theory of natural selection; if humans had evolved instead of being created, then the Bible’s account of creation must be inaccurate. This clashed with a growing fundamentalist movement within the church that held the Bible to be literally true, and it worried opponents already grappling with the major societal changes wrought by modernity, urbanization, and the First World War.

By the 1920s, national figures like William Jennings Bryan, a popular orator and politician, and popular evangelical radio star Aimee Semple McPherson were speaking out against teaching evolution in schools.

In response , Tennessee passed the Butler Act in March 1925. Named after its sponsor, state representative John Washington Butler, the law prohibited teaching “the Evolution Theory” in all publicly funded educational institutions in Tennessee, making it unlawful “to teach any theory that denies the story of Divine Creation of man as taught in the Bible.” Violators would get a misdemeanor and be fined between $100 and $500 for each offense.

Who was John Scopes?

Though there was little opposition to the law before its passage, it caught the attention of civil rights activists looking to preserve the separation of church and state. As increasingly orthodox Protestants sought to extend religious teachings into public school classrooms, opponents tried to keep religion out of public, secular schools. Evolution was a stress test for public education, with scientific inquiry colliding with the fear that learning about evolution might destroy organized religion.

The new American Civil Liberties Union, first founded to resist wartime checks on free speech, was in search of a test case against anti-evolution statutes it considered to be an unconstitutional violation of religious liberties.

“We are looking for a Tennessee teacher who is willing to accept our services in testing this law in the courts,” wrote Clarence Skinner, one of the ACLU’s founding members, in a widely publicized advertisement in 1925. “Our lawyers think a friendly test can be arranged without costing a teacher his or her job.”

The ad, and the controversy surrounding evolution, sparked the interest of a group of civic boosters from Rhea County, Tennessee, an economically depressed area that had recently experienced a massive population decline. Convinced a controversial trial would boost the region’s profile, they met with John T. Scopes, a 24-year-old football coach and part-time high school teacher at Rhea Central High School in Dayton.

“Although not a trained scholar, I thought Darwin was right,” Scopes later wrote in his 1967 memoir. Although he was unsure whether he had taught evolution as a substitute biology teacher, he told these civic boosters that he believed he had helped students review for a final exam that involved the theory. One of them then arrested Scopes, and a trial was set for that summer.

Evolution and creationism on trial

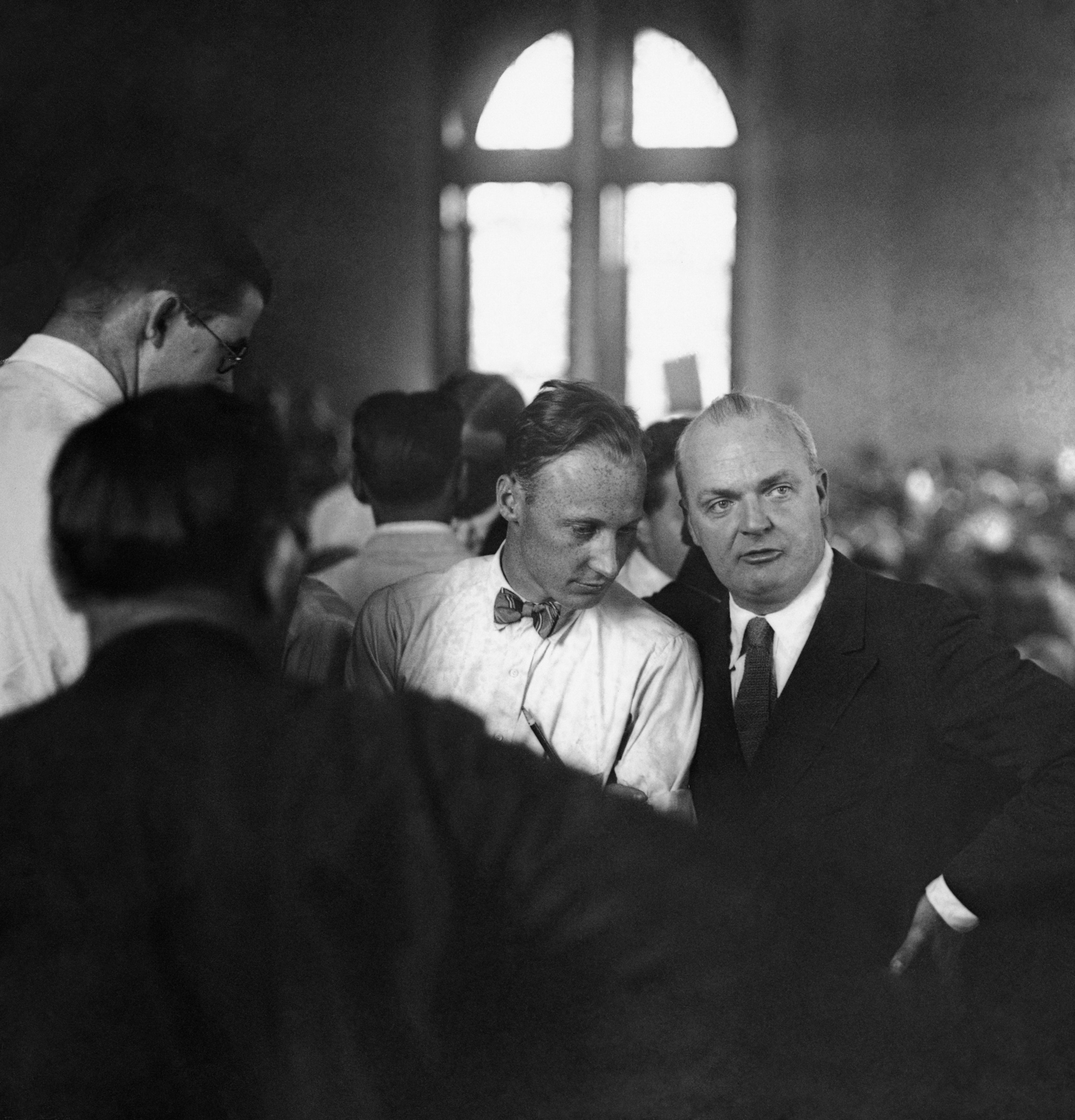

The trial pitted the theory of evolution against religion—and set the stage for one of the greatest battles in legal history. Clarence Darrow, a high-profile attorney known for his dramatic defenses and massive salary, was to represent Scopes and the ACLU, while Bryan agreed to assist the prosecution.

The presence of two of the world’s most famous men, and the explosive subject matter of the debate, turned sleepy Dayton into a destination. Reporters and spectators crowded into town, and the trial was covered in breathless detail. It was, in the words of historian Tom Arnold-Foster, “a fraught national circus” that “dramatized a series of interlocking cultural conflicts between science and religion, urban and rural, elite and popular, North and South.”

Every day, the trial began with a spoken prayer, and an all-male, all-white jury, most of them practicing Christians, listened to the verbal fireworks that accompanied Darrow and Bryan’s cases. Though a criminal case, much of the defense’s testimony revolved around the validity of the theory of evolution, with witnesses stating that evolution was commonly accepted among scientists. Meanwhile, the prosecution’s witnesses testified that Scopes had indeed taught evolution.

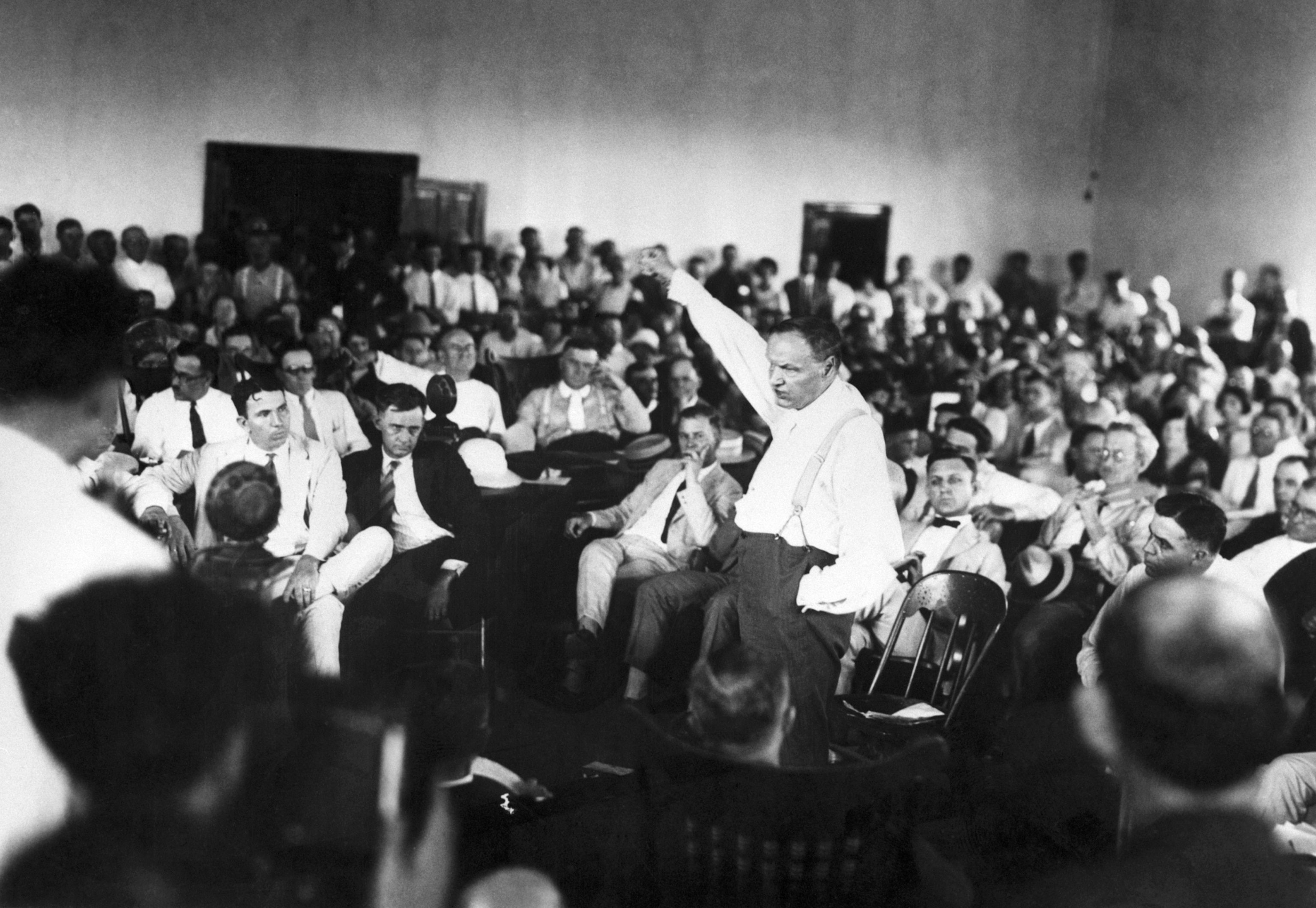

Finally, Darrow made the unusual move to call the prosecution’s own counsel as an expert witness on the Bible. Now, Darrow closely questioned Bryan himself on matters of theology and science. By then, the case had been moved outdoors in a nod to the stifling summer heat inside the courthouse and the thousands of spectators gathered to see the defense and prosecution tussle.

A turning point in the debate over evolution

Grilled on the ins and outs of Genesis, Bryan faltered and tripped over his own words, making it clear that he only believed some portions of the creation story were literally true. The examination climaxed with Bryan’s accusation that Darrow was only there to “slur at the Bible,” accusing him of atheism and of using the court to spread his anti-Christian ideas. Darrow replied that Bryan had “fool ideas that no intelligent Christian on Earth believes.” Bryan’s testimony was eventually struck from the record after the judge decided it was irrelevant. Bryan’s testimony was eventually struck from the record after the judge decided it was irrelevant.

Finally, Darrow requested that the case be directly sent to the jury, a move that prevented Bryan from making a convincing final case.

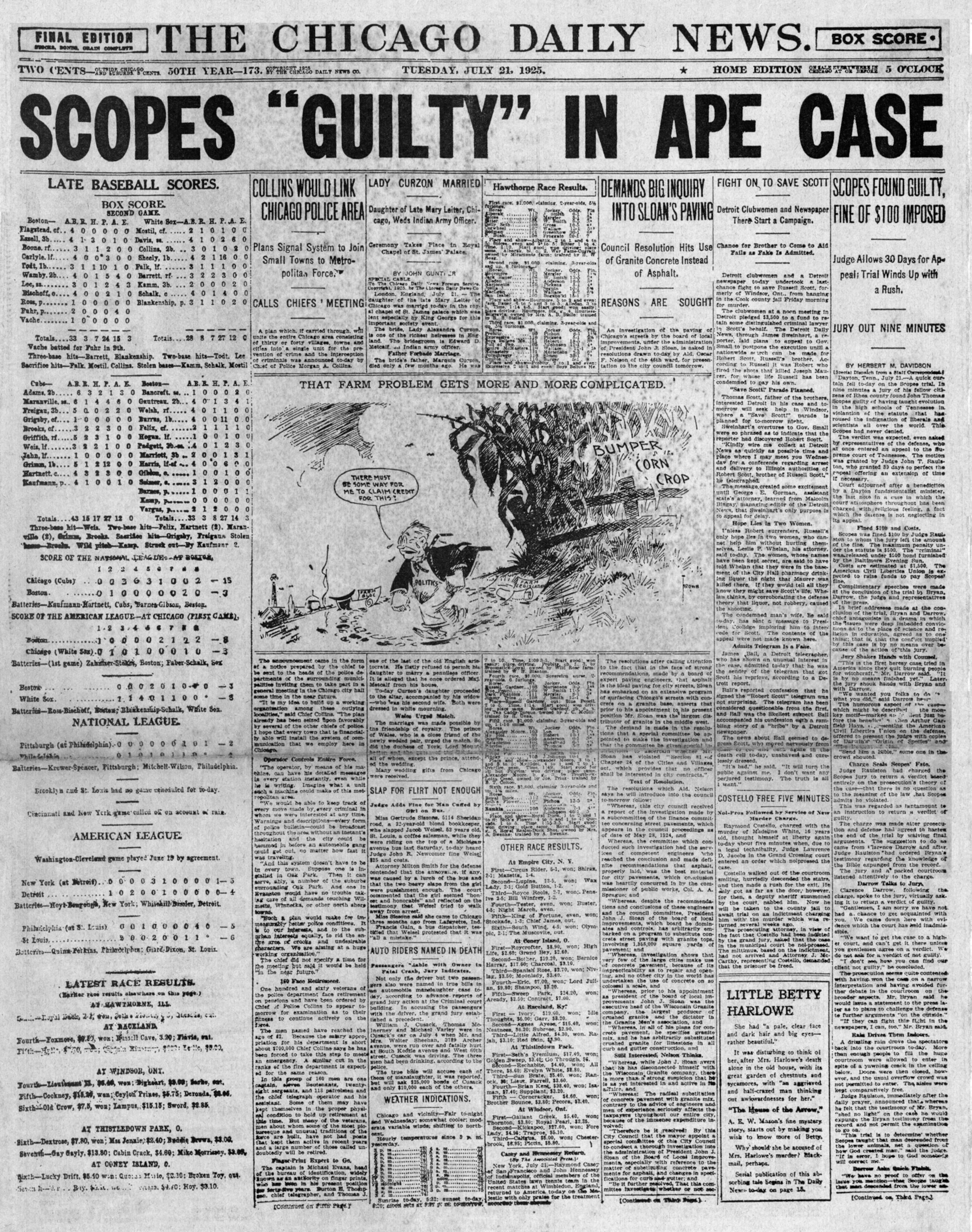

Still, Bryan’s side prevailed. In less than 10 minutes, the jury decided Scopes was guilty. He was fined $100.

Scopes made just one statement during the proceedings. “I feel that I have been convicted of violating an unjust statute,” he told the judge after the verdict was passed down. “I will continue in the future, as I have in the past, to oppose this law in any way I can.” To act otherwise would compromise his academic freedom, Scopes said.

Bryan had won the case, but had been publicly humiliated. Just five days later, he died of “sudden apoplexy.” Though Scopes appealed, the case was eventually dismissed on a technicality.

The test case had failed to protect Scopes for possibly having taught evolution, but it carried out its main purpose: to publicize the evolution and education issue and raise awareness of potential conflicts between church and state.

Why was it called the Scopes ‘Monkey’ Trial?

Given the massive media interest, the Scopes trial was the first case in American history to be broadcast live on the radio. The technical details of evolution also forced journalists to write more detailed scientific reports.

The trial’s contested subject matter was also an opportunity for intrepid journalists like the Baltimore Sun’s H.L. Mencken. A journalist and free-speech advocate, Mencken became the unofficial, often caustic voice of the trial. Dubbing the proceedings “The Monkey Trial,” a nod to the furor over whether humans had descended from monkeys or been created by God, Mencken took aim at Bryan and the prosecution, calling Bryan “out-generaled and outargued” by Darrow.

Laws prohibiting teaching evolution would stay on the books for decades more, with Tennessee’s law only being repealed in 1967. By then, the Scopes Monkey Trial had become a legal and scientific legend, thanks in part to the 1955 play Inherit the Wind, which portrayed the anti-evolution movement as analogous to McCarthyism.

The lasting impact of the Scopes Trial

Nor have questions about science’s potential to upend religious authority faded in the century since the trial. Today, a broad scientific consensus supports Darwin’s idea of evolution by natural selection, and everything from the fossil record to evidence contained in human red blood cells supports the idea that humans evolved from a common ancestor.

But the Scopes trial still serves as a symbol of an ongoing struggle between conservatism and progress, religion and secularism, evidence-based science and scientific misinformation.

Timeline of Tennessee v. Scopes

March 21, 1925: Tennessee legislature passes the Butler Act, which is signed into law by Tennessee governor Austin Peay.

May 1925: Civic boosters convince John Scopes to take on a test case and arrest him.

July 10, 1925: The State of Tennessee v. John Thomas Scopes convenes in Rhea County.

July 21, 1925: Jurors find Scopes guilty, and Judge John Tate Raulston fines him $100.