Syphilis DNA Pulled From Colonial-Era Bones

The 350-year-old genes may help researchers settle the debate about where the disease originated.

In 1494, just after Columbus' first voyage to the New World, historical accounts in Europe describe a debilitating epidemic of a previously unrecorded disease that we know now as syphilis. That timing has sparked a debate that remains unanswered in modern science: Was syphilis, a sexually transmitted disease currently on the rise in the U.S., brought back to Europe from the Americas with early explorers, or was it already present in populations east of the Atlantic?

Previous methods of finding the disease's origins have relied on historical accounts describing the disease, or by identifying lesions on skeletal remains. The problem, however, is that many described symptoms as well as visible lesions characteristic of syphilis can also be caused by yaws, a disease caused by a different subspecies of the same bacteria, Treponema pallidum. Unlike sexually-transmitted syphilis, yaws is a disease spread simply through skin-to-skin contact, and often causes lesions and ulcers.

Now, scientists have developed a way to genetically discern the difference between the subspecies of syphilis and yaws in human remains, and they say this advance can help reveal the disease's mysterious origins.

A Closer Look

Researchers first began by looking for skeletal human remains that had signs of bone lesions, indicating they once harbored the bacteria that causes syphilis. Five sets of human remains with visible bone deformations were selected from a cemetery at the Convent of Santa Isabel, a historic site in Mexico City run by nuns of the Franciscan order from 1681 to 1861. Of those five, three sets of infant remains had DNA that tested positive for Treponema pallidum.

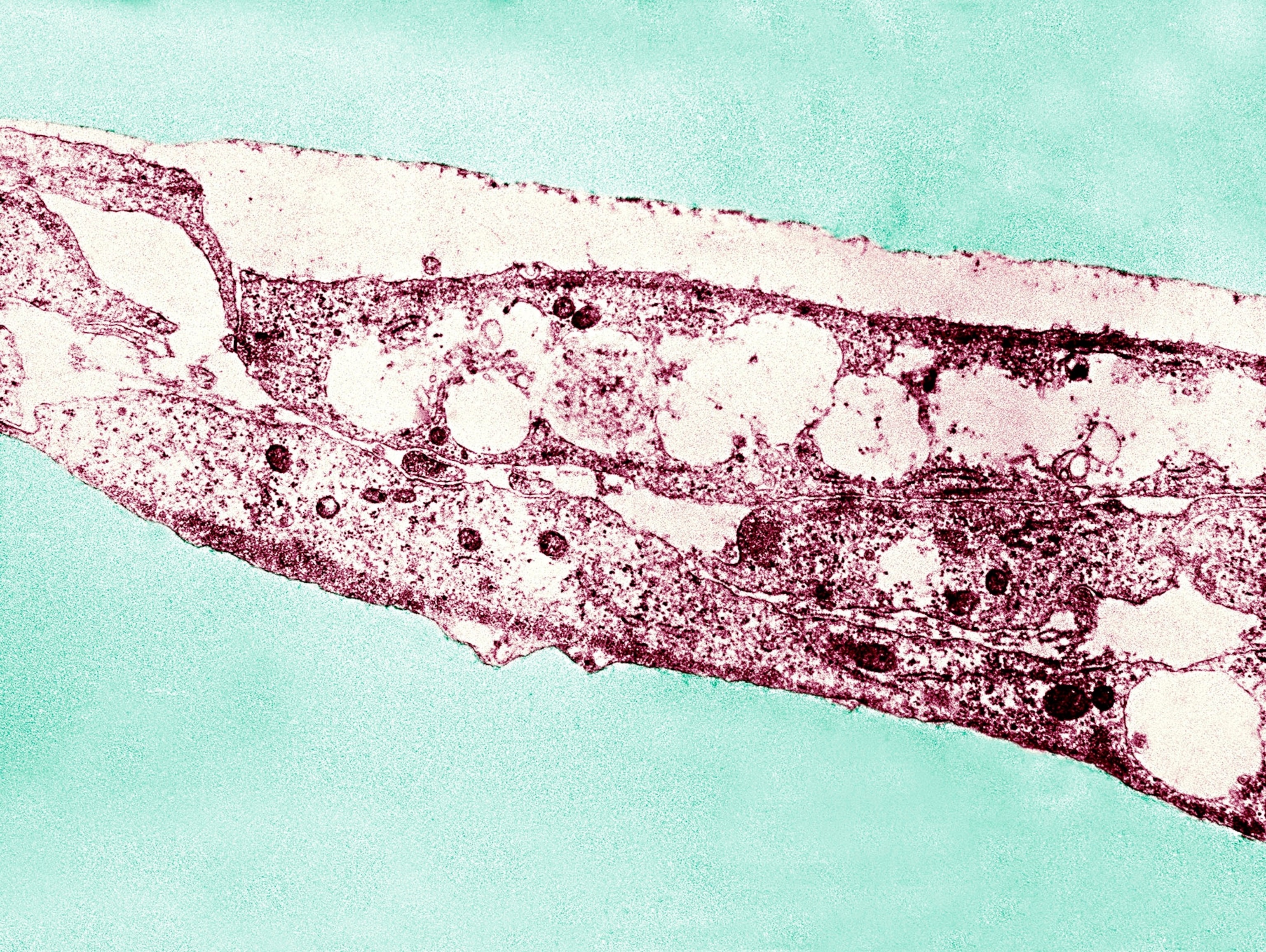

“Our strategy was to look at neonatal infants already infected with syphilis and therefore more likely to have a higher pathogen load,” says Verena Schuenemann, the first author on a paper detailing the find in the journal PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases. Infants contract syphilis from their mothers during gestation and, because their immune systems are still weak, harbor higher concentrations of the bacteria.

Geneticists then isolated the historic syphilis genomes for the first time and were able to identify subspecies of the syphilis-causing bacteria in two of the individuals, and a subspecies of the yaws-causing bacteria in the other individual.

“Now, with the methods used here , it's possible to go farther back in time and look at Pre-Columbian syphilis and see where it originated,” says Schuenemann.

It Takes Patients

While the genome sequencing technique on historic remains presents an exciting new tool to study the disease, Mississippi State University anthropologist Molly Zuckerman says finding sets of human remains to test will be the biggest hurdle.

That's because a number of diseases leave bone lesions—the visible marker researchers often look for to identify a skeleton with syphilis—and only the worst cases of syphilis will leave visible bone deformities.

To track down earlier diagnosable cases of syphilis, “the next step is to look at different samples,” says Schuenemann. “We have no idea if the strains found in colonial Mexico are the same found in Europe.”

One 2016 study published in the International Journal of Paleopathology looked at a 2,200-year-old adult male skeleton from northern Chile. The remains showed signs of a thoracic aortic aneurysm, which is sometimes seen in people with severe syphilis, and led the study's authors to suggest it was an early example of the disease. Without the technology now available to researchers, however, it was unclear if the man was actually suffering from yaws.

“You cannot distinguish [the disease] skeletally, but that we can do it genetically is exciting,” says Zuckerman, whose work focuses on the evolution of infectious diseases. Her own research has led her to suspect that the treponema bacteria originated in the New World, manifesting as yaws and spread through skin-to-skin contact exposed by a warm climate. When the pathogen then spread to Europe, more temperate weather meant skin-to-skin contact occurred more frequently through sexual contact, forcing the bacteria to evolve.

“In terms of skeletal evidence,” Zuckerman notes. “We did not find any cases from the Old World that predated Columbus.”

Diagnosing Syphilis, Earlier

Understanding the bacteria's evolution may also help medical researchers better understand how to diagnose the disease in its early stages.

“Getting insights into how virulence has changed in the past can inform better diagnosis [today],” notes Zuckerman. Current tests are more effective at diagnosing the disease in its later stages, but a better understanding of the bacteria's evolution could help medical experts diagnose syphilis in its early stages.

It's a treatment badly needed as syphilis continues to make a comeback. From 2014 to 2015, cases reported to the Centers for Disease Control rose by just over 17 percent, and it continues to surge around the world.