The end of the Afghanistan I knew

I chronicled jubilant homecomings after the fall of the Taliban. 20 years later, their return to power brings back painful memories and panic.

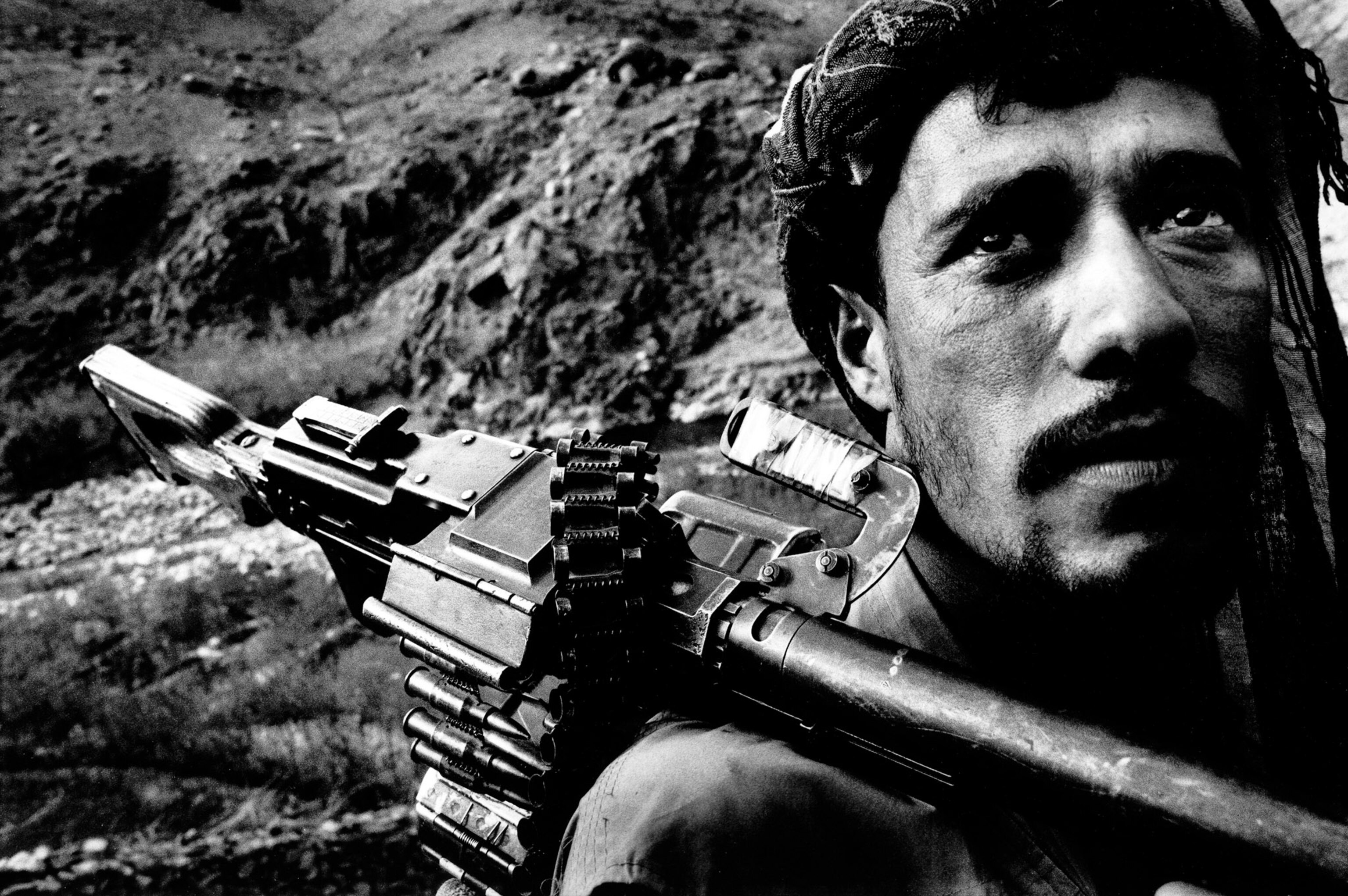

On a gray winter morning in 1999, I stood on a sidewalk in downtown Kabul. The city was deserted, emptied by war and fear. Occasionally, a pickup truck careened by, carrying turbaned men with rifles who shouted at stragglers late for afternoon prayers. Otherwise, the only sounds were the click of bicycle spokes and the clip-clop of horse-drawn carts, carrying piles of wilted cauliflower or scavenged cardboard.

In half-abandoned neighborhoods, old cement and mud-brick walls were crumbling and pocked with bullet holes. Ragged families had made camp in ruined houses, hanging sheets across doorways and setting up cookstoves amid rubble. Children peered out for an instant, then quickly drew back into the shadows. There were no women in sight.

As a journalist and foreign “guest” of the Taliban regime, I was escorted with stiff politeness to offices and historic sites. In one dank ministry, the only official sat cross-legged and barefoot in a chair. At the deserted national palace, the heads of marble fish had been knocked off a courtyard pool and the faces of pheasants scratched off tapestries, because the Taliban viewed depictions of animals or humans as blasphemous. The sight was chilling.

Fast-forward

Several weeks ago, I found myself at the same intersection. This time I was stuck in sweltering rush hour traffic—a daily ordeal in the noisy, crowded metropolis of five million. Overhead, blinding video screens advertised the latest smartphones and construction cranes swayed near half-built high-rises. On the sidewalks women haggled with fruit sellers, and beauty parlors featured posters of pouting geishas.

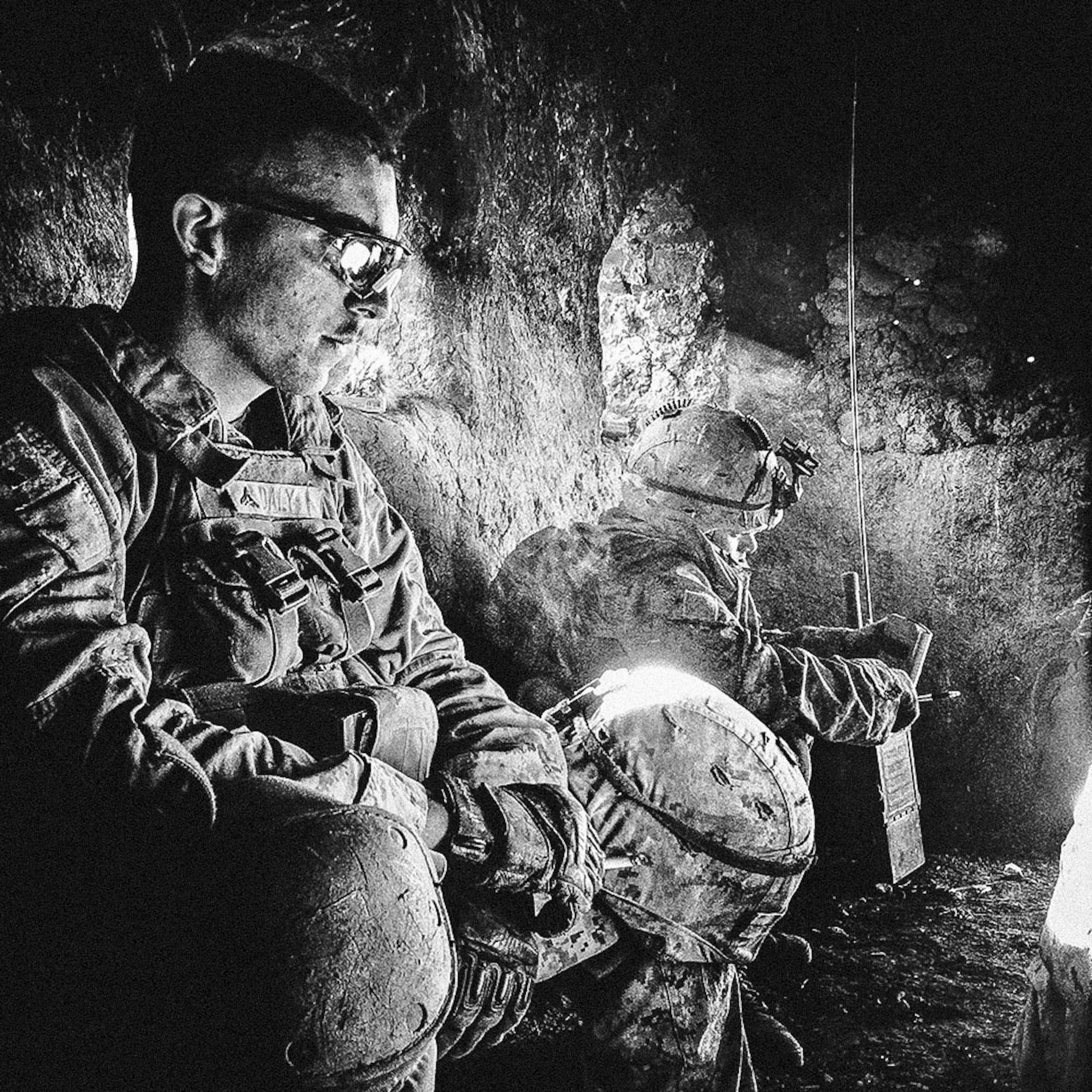

There were also blast walls across the city, and police checks had intensified following a spate of bombings and targeted killings in recent months by a resurgent Taliban and Islamic State. But two decades after the attacks of September 11, 2001, which prompted the United States to invade Afghanistan and topple the Taliban, Kabul looked like any fast-growing city in the developing world, moving up and into the 21st century.

So it felt like whiplash in mid-August, when I watched the news with horror as scenes of chaos unfolded in the Afghan capital from my home in northern Virginia. After a lightning-fast advance timed to coincide with the withdrawal of the last U.S. troops from America’s longest modern war, the Taliban had seized power once again. Thousands of panicked people were desperately trying to reach the same airport out of which I had flown a hundred times. For those who remained behind in Kabul, a blanket of fear was descending.

My mind immediately went to the fate of Afghan friends who had reason to fear the insurgents’ wrath—Nader Nadery, a longtime human rights activist I had met soon after the Taliban fell in 2001; Davood Moradian, a liberal academic whose institute was in a historic fort overlooking the city; Haroun Mir, a political scientist and aide to the senior vice president, Amrullah Saleh.

“I left with just the clothes I was wearing,” Mir, still in shock, told me from a relocation center in France. He recalled our many discussions of Afghan politics over tea, and the long-ago spring weekend when I had visited his late father’s farm north of the capital. Then he paused and sighed. “We’re lucky, at least we got out as a family.”

Post-Taliban spring

For long stretches of time over the past two decades, Kabul was my second home. It was run-down and war-scarred, but it offered a ringside seat to history: the ambitious effort to build a civilian democracy on the ashes of Soviet invasion, civil war, and religious repression, and to fashion a modern state in a poor, tribal society stunted by decades of strife.

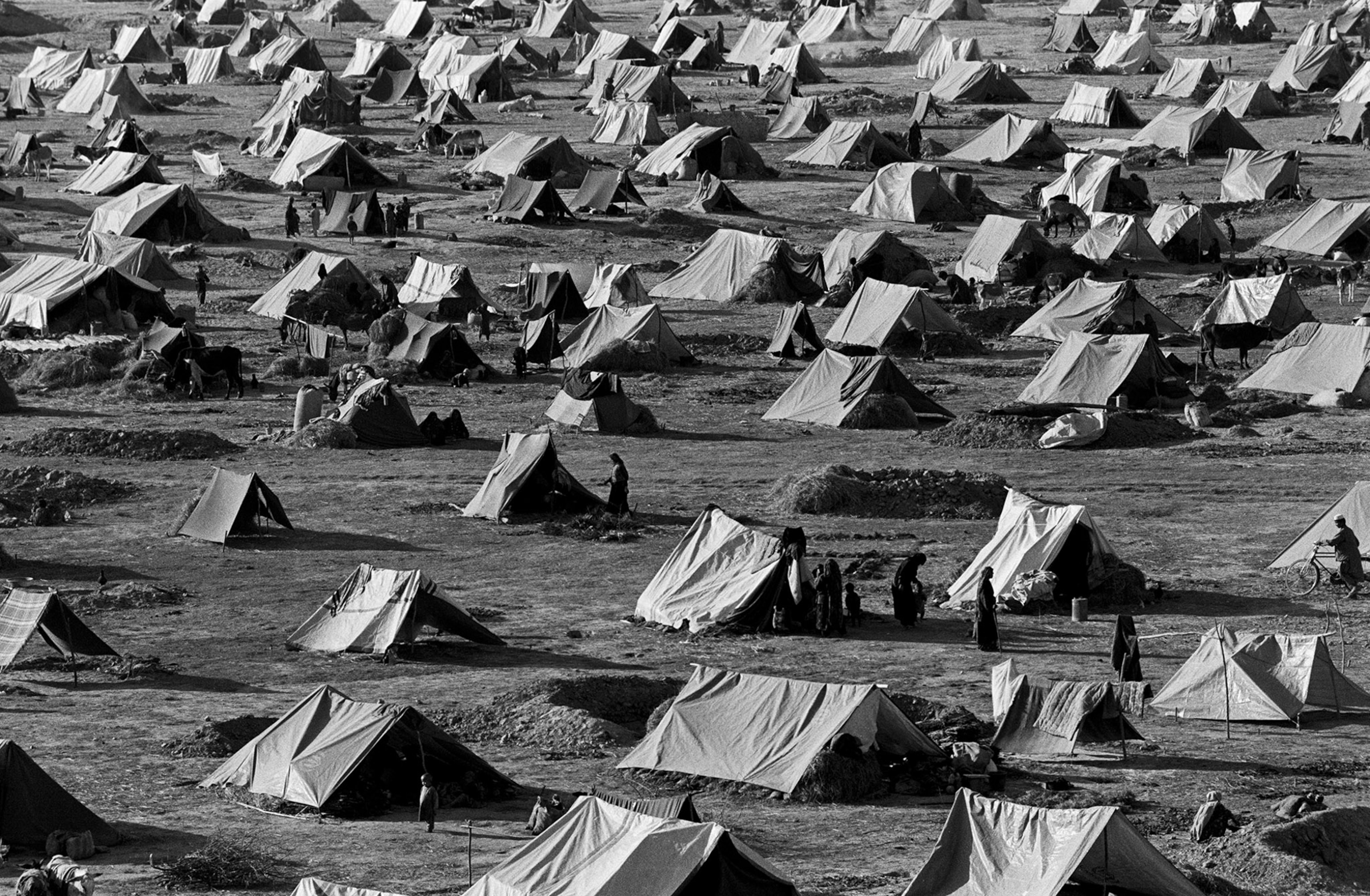

At first, being there was a grand adventure, with a story on every corner. Foreign experts and exiled politicians jetted in from Europe; refugees who had fled decades of war to Pakistan piled their belongings into dusty cargo trucks and chugged back home across the border.

Freed from the Taliban’s strictures, men were getting their beards trimmed for the first time in years and women were flinging off suffocating burkas with relief. I watched in awe as families eager to return to their homes in northern Afghanistan used pickaxes to chop their way through a frozen tunnel on the only major route connecting Kabul to the north.

Soon, enterprising Afghans were opening English-language academies, hair salons, and construction companies. Money poured in. A new constitution was written; elections were held; highways were repaved and irrigation systems repaired. Embassies held cocktail parties; NATO set up headquarters in an old mansion, and U.N. agencies gobbled up block after block.

It was easy to travel to other provinces then; the country was safe and the Taliban minders gone. Climbing into our driver’s 1963 Landcruiser, my colleagues and I would head south to interview opium poppy farmers or north to see the famous 500-year-old Buddha statues in Bamyan, half-destroyed by the Taliban as “un-Islamic.” Everywhere, villagers greeted us politely and swarms of excited children called out, “Haraji!! Haraji!!” to announce that foreigners had arrived.

If we were really lucky, a nomad caravan would appear in the distance. We would turn off the engine, listen to the camel bells jingling faintly, and watch the flocks and shepherds as they padded unhurriedly across the paved road, continuing on their invisible trail, and slowly vanishing into the desert haze.

Disillusionment

The largely warm welcome for Americans began to fade after the US invaded Iraq in 2003 and shifted its attention. Meanwhile, the Taliban, whose members had been hiding in the countryside and in next-door Pakistan, began to re-emerge. I first felt it in the spring of 2006, when an American Humvee hit a pedestrian in Kabul and an enraged mob swept through the city, looking for foreign targets and ransacking the offices of CARE International. Several rioters with guns commandeered my driver’s car, and one spotted a box of books I was sending to a high school teacher. Seeing the address in English, he stabbed the box with a bayonet.

After that, it seemed, some of the hopeful stories I had written rang less true. Many promising and eloquent Afghan leaders proved corrupt or venal, and others whom I came to trust or admire met violent ends.

One was Ghulam Haider Hamidi, a mild-mannered émigré in his 60s who had lived quietly in northern Virginia for years, working as an accountant. In 2007, he returned to his hometown to accept a post as the mayor of Kandahar, Afghanistan’s second-largest city.

I flew to Kandahar to meet him. Hamidi spoke enthusiastically about his vision for improving the old desert city, planting trees in vacant lots, and bulldozing squatters’ shops. But he made enemies in the process, and while on his way to a community meeting in 2011, he was assassinated by a suicide bomber.

Three years later, I lost my friend Kamel Hamade, the owner of a lively Lebanese bistro in Kabul where I often met friends for dinner. The war had become relentless, and the Taverna du Liban had become a haven, for a few hours, from the tensions swirling outside. Kamel was a genial host who served wine in china teacups, and a fellow animal lover who never let me pay for a meal, saying I should save my money to feed stray dogs and cats.

One day in 2014, I was back in Washington when I received an ominous phone message about an attack on the Taverna. Taliban commandos had bombed the front door and gunmen had burst into the dining room. Within two hours, the news was confirmed. Kamel had been shot dead, along with all 21 dinner guests. After that, I never really felt safe in the city again.

Other deaths followed; some that didn't count as casualties of war, but were outgrowths of the instability it created. I once spent a week following a gang of scavenger boys on their early morning rounds in my neighborhood, poking into gutters and dumpsters for bottles and cans, and stuffing them into dirty shoulder sacks.

It was winter, but none had hats or gloves, and some had no socks either. They went to school a few hours each day, and their meager income from trash-picking was vital to their families, many of whom had been displaced from their villages by fighting or were former refugees, struggling to make ends meet after returning from Pakistan.

One boy, an impish 11-year-old named Hamid, always waited outside my corner grocery store at dusk, hoping for handouts. I often gave him a candy bar, which he shared with his little brother. One night, after I had been away for some weeks, I noticed Hamid was missing. He had been struck and killed by a car while walking home after dark.

The next day, I found my way to his home. There were 27 people inside, crowded around a single wood stove. The boy’s father, Mohammed, told me they had fled their village during the Soviet invasion, and that he later lost his leg in a bombing. Of his nine children, Hamid had been the most industrious. “He wanted to study, but we counted on him,” the father said. “I don’t know what we will do now.”

Perseverance

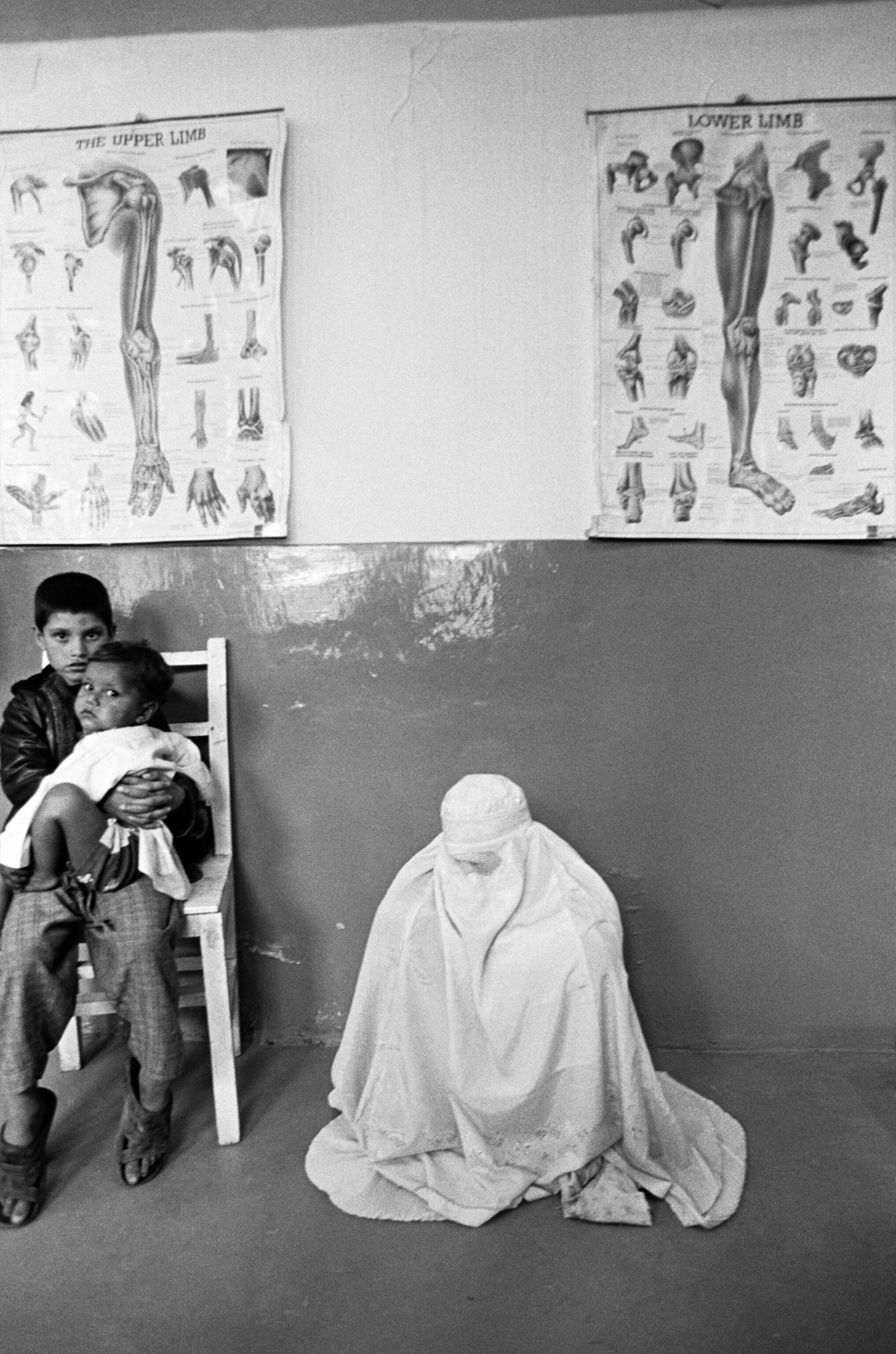

Sometimes I wrote about people who faced a living death, especially the Afghan soldiers and police who lost several limbs in the war. Since the 1980s, successive Afghan conflicts had produced new bombs and other weapons that didn’t always kill, but left ghastly damage. With their prospects for work and marriage diminished, some badly maimed victims lost their will to live.

But at an orthopedic rehabilitation hospital in 2016, I met a young soldier who was determined to go on. Jawad Mahmoodi, then 26, had lost both legs in a land mine explosion while on combat duty in Kunduz province.

In a training room, he was stone-faced as he bent over and struggled to fasten his new steel legs onto plastic waist supports. Half a dozen other young amputees, slumped in wheelchairs, watched him gloomily. Finally, with a triumphant grin, Mahmoodi heaved himself up between two exercise bars.

“I sacrificed for my country. Now I am trying to get strong,” he declared. “I want to stand on my own feet.” It was far from clear whether he would ever walk again. The fighting in Kunduz continued for years, but for a moment that day, as Mahmoodi lifted himself up, the mood in the room brightened.

There were also times when I wrote about the deaths of people I had never met, whose names I never knew, or who had been buried hastily with only jagged stones for a marker. Often, they were random victims of terrorist bombings who had been riding a bus, selling mangoes on the sidewalk, praying in a mosque, or walking home from school.

Early one morning in May 2017, I visited a nature preserve about 10 miles from Kabul. It was a beautiful day, and we were watching birds soar over a marsh, when the earth shook with a powerful boom. A garbage truck packed with explosives had detonated outside Kabul’s fortified diplomatic zone, incinerating vehicles and killing workers at their office desks. Eighty people died, and more than 400 were wounded.

I rushed back to the city and spent the next seven hours outside a hospital, where ambulances kept arriving with bags of corpses, many burned and dripping blood through the zippers. I had no translator with me, but there was no need for one. I watched and listened as clusters of men waited for news, fingering prayer beads.

One of them, a dignified man in his 50s, recognized the remains in one bag. He wiped his eyes with his woolen shawl and mumbled into a phone. I heard him say the words in Dari for “brother” and “martyr.” Like others who died that day, his brother was a random victim of an act intended to instill Afghans with a permanent sense of fear.

Assault

By the time Taliban forces were steaming across the country last month, most Afghan government troops had given up entirely. They had been trained and equipped by Americans, but they had never really felt comfortable fighting their fellow Muslims and countrymen in what the Taliban branded an invaders’ war. While the insurgents burned with religious conviction, disgruntled government troops often went without pay and ammunition.

Still, I was stunned last month that the Taliban toppled the U.S.-backed government so swiftly and decisively. And as I tracked their accelerating path toward victory, I recognized place after place that I had visited in earlier times. Some conjured pleasant, peacetime memories; others were grim glimpses of war’s cruelty and vertiginous fortunes.

When the Taliban captured Logar province, I remembered stopping there to buy honey from roadside beekeepers. When they overran Helmand, I thought of the elderly village teacher whose school had been destroyed by bombing, but who had covered his home library with delicate hand-drawn pictures of birds and flowers.

When the Taliban last month took Shibirghan, the northern stronghold of a notorious anti-Taliban warlord, Abdul Rashid Dostum, I remembered a haunting visit with other journalists to a prison where Dostum had kept captives. In 2001, he had reportedly suffocated hundreds of Taliban fighters in airless shipping containers and kept many more locked away in a private prison. When we arrived, not long after the Islamist regime had fallen, we beheld a derelict compound crammed with gaunt, filthy men, some of whom had been forcibly conscripted by the Taliban.

That day, in a show of benevolence, Dostum was to release some of them. Their families had traveled hundreds of miles to meet them. When the gate swung open, the young men filed out hesitantly, some limping. One recognized his father, who wrapped the emaciated boy inside his shawl and wept. It was one of the saddest scenes I had ever witnessed.

When the Taliban last month seized Herat, an ancient, cultured city near the border of Iran, I thought of Ismael Khan, another storied militia leader who became the region’s post-Taliban governor. Once, Khan invited a group of Western journalists there to showcase his popularity and prowess. First, he kept us up long past midnight while he held court with grateful petitioners, then sent for us the next morning to watch him gallop a strong white horse across a grassy plain.

Years later, on a very different visit to Herat, I sensed that the balance of power had shifted irrevocably. During a short-lived ceasefire in 2017, Taliban leaders were expected to mingle with local elders and politicians. Instead, the meeting collapsed when Taliban fighters insulted the government, brandished weapons, and shouted war slogans. I left feeling shaken and shocked.

And now, here was Khan on the news, the once-proud resistance leader, slumped glumly in a chair as he surrendered his forces, having succumbed to the relentless forward march of the Taliban.

At the gates

Finally, on August 15, when the Taliban marched up to the gates of Kabul, I thought back wistfully to the spring of 2002, when the men with guns and whips had fled, and thousands of refugees began streaming back from Pakistan.

One morning I had joined a caravan of families who had piled their bedding and cooking pots into rented trucks, with chickens and children perched on top. We chugged along, past sprouting fields and ancient eucalyptus groves, zig-zagging through mountain passes and tunnels before descending to the Kabul plain.

Soon after we entered the city, the convoy veered onto a dirt track, sending up clouds of dust. When we reached a deserted cluster of mud-walled houses, we stopped and everyone clambered out excitedly. An old man placed a Quran, wrapped in cloth, above the door frame. The family was now officially home.

A rug was rolled out on the dirt floor, and everyone sat down for lunch. After a prayer, a large bowl of meat sauce and a dish of yogurt were placed in the middle. Each person dipped bread into the sauce in turn, then sipped yogurt from a ladle and passed it on.

After years in exile, they were returning to a country finally at peace, and I realized what an honor it was to be included in their homecoming meal. I took a sip from the ladle and passed it on.

Full circle

Now, nearly two decades later, the Taliban are suddenly back in power, and that long-ago moment of grace seems like a distant dream. In Kabul, turbaned clerics have promised to treat civilians more kindly, but their scowling young Taliban enforcers have beaten panicked crowds trying to reach the airport and women protesting to preserve the rights they gained in the last 20 years. In rural areas, there have been reports of cruel retribution, and there’s no indication the militants’ harsh interpretation of Islamic law has softened. It’s not hard to imagine Kabul becoming the same cowed and deserted city I visited 22 years ago.

Two indelible scenes from that time have always stayed with me. One was outside the feared Taliban Ministry for the Promotion of Virtue and Prevention of Vice. As I waited for an interview with the minister, two officials hustled in a sobbing young man. I was told he was to be punished because his beard did not meet the required length. The specifications were crude but simple: some hair had to show beneath a clenched fist held under a man’s chin—or else.

The other was in a city park, where I watched a crowd of hungry people waiting for a food donation truck. Guards had forcibly separated them by gender, according to Taliban strictures. When pushing and jostling broke out, the turbaned security men descended on the crowd, wielding electrical cables, and beat everyone back into their rigid lines.

Pamela Constable, a former Afghanistan bureau chief for the Washington Post, has been reporting from South Asia for more than two decades.