These women unlocked the mysteries of the deep sea

On a record-breaking expedition in the 1930s, one group of women—a scientist, an artist, and a researcher—helped define the science of the sea.

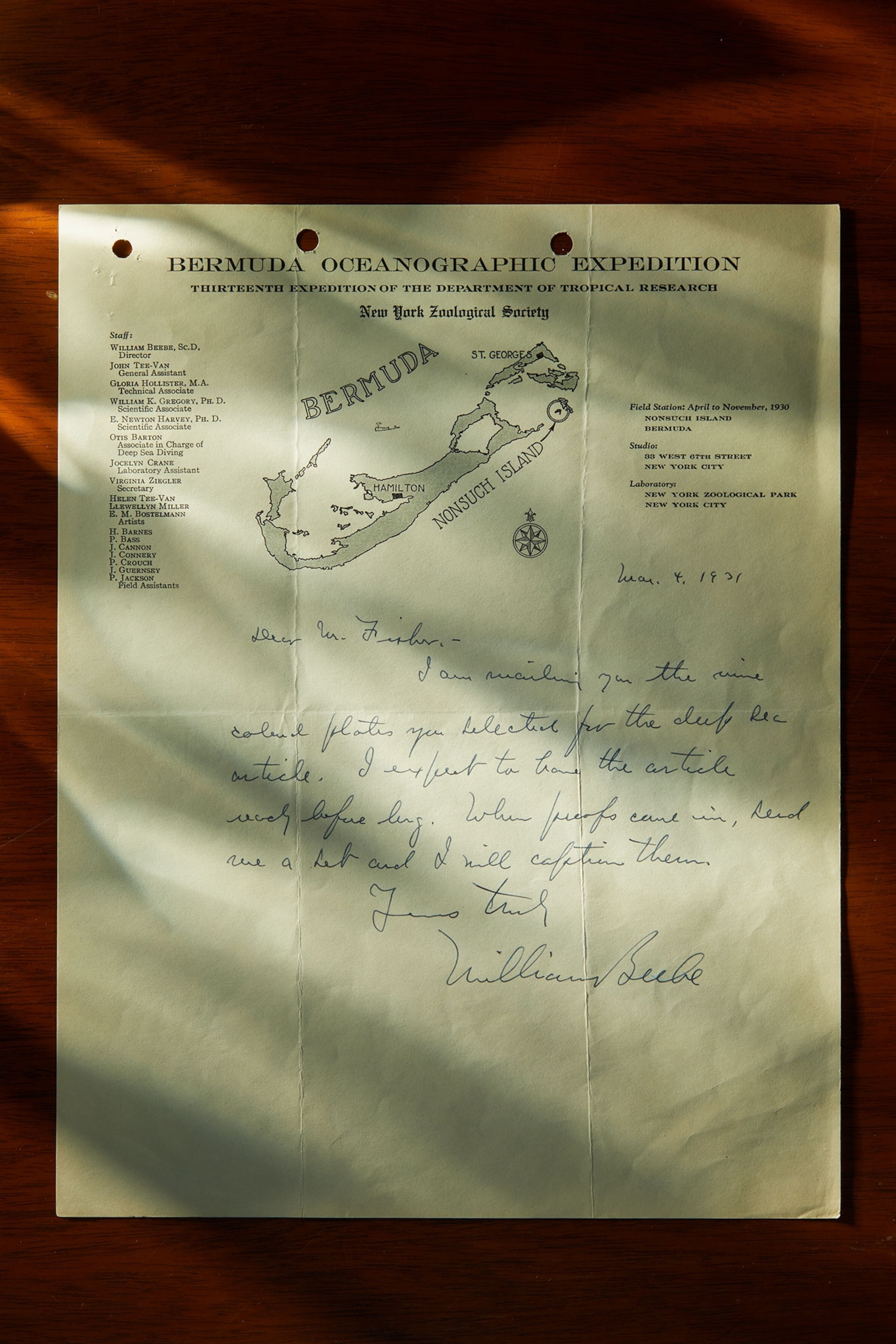

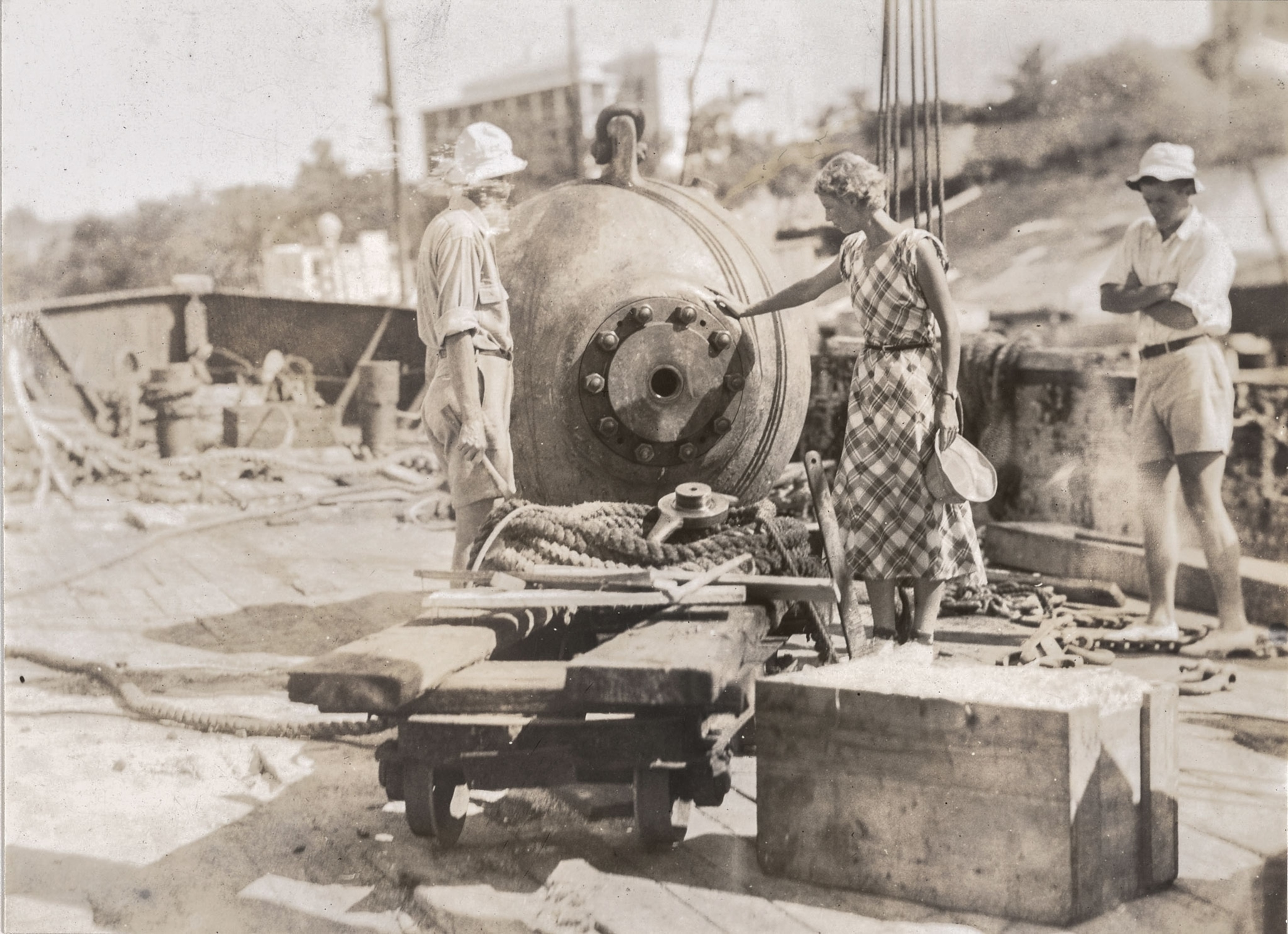

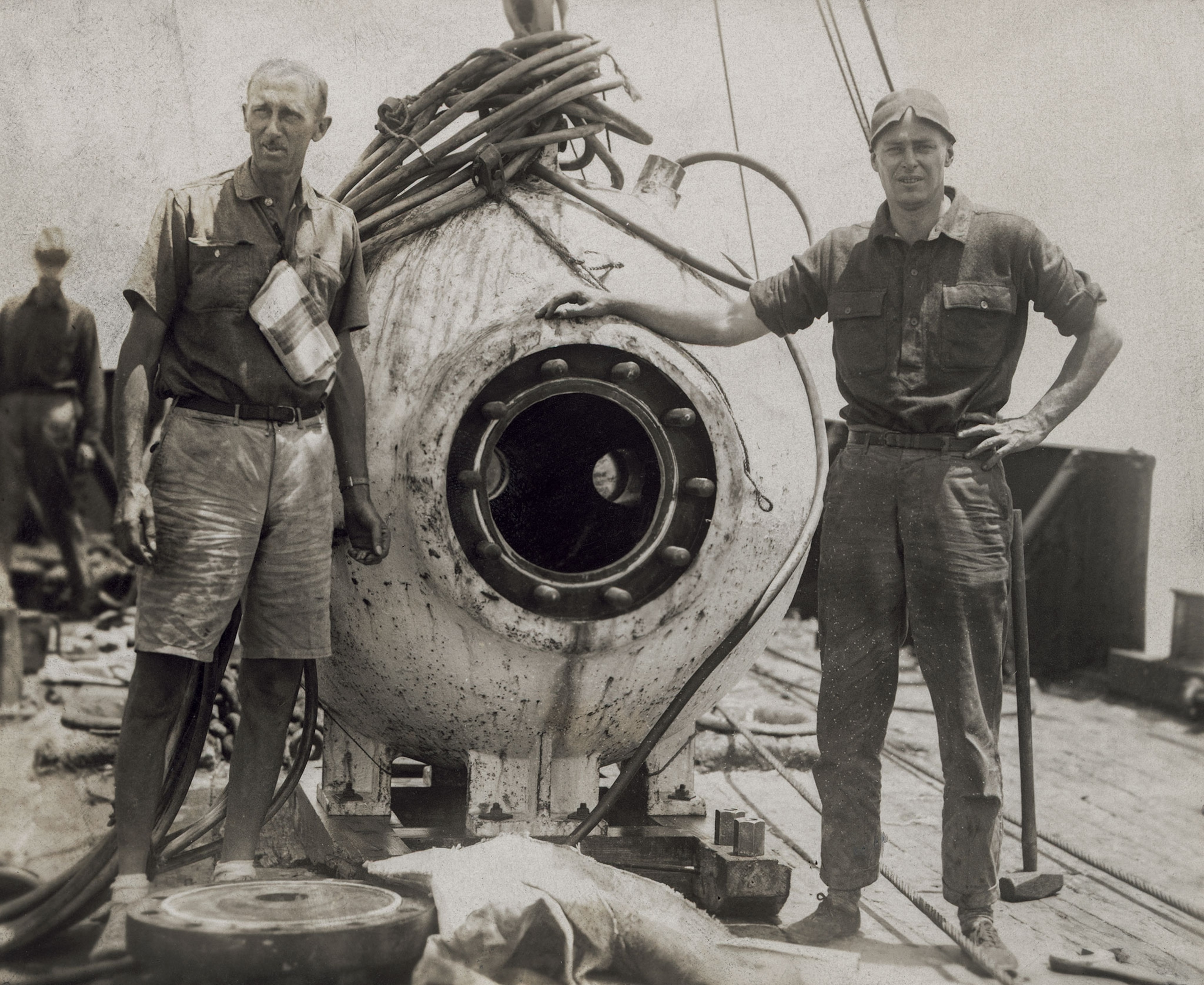

In 1930 underwater explorers William Beebe and Otis Barton were lowered into the Atlantic Ocean near Bermuda in a tiny steel orb called a bathysphere. It was the first serious foray into crewed deep-sea exploration, and soon it would be international news.

The world of life they saw, wrote Beebe in a 1931 National Geographic story, was “almost as unknown as that of Mars or Venus.” Modern oceanography, he added, knew as much about the deep sea as if a student of African animals was studying rodents but didn’t yet know there were elephants and lions roaming the wild.

Above the water, a group of female scientists ensured that this bold new contraption operated without a hitch. From the boat deck, laboratory assistant Jocelyn Crane Griffin helped identify the marine life. At the phone was Gloria Hollister Anable, the chief technical associate for the Department of Tropical Research at what is now the Wildlife Conservation Society, which supported the mission. This phone connection, via a cable that ran from the vessel to the ship, was Beebe’s only lifeline to the outside world, and it was never supposed to go silent. (In one picture she’s perched on a wooden crate with headphones wrapped around her head and the caption notes, “When communication was interrupted she had no means of knowing whether it was from static or a fatal accident.”)

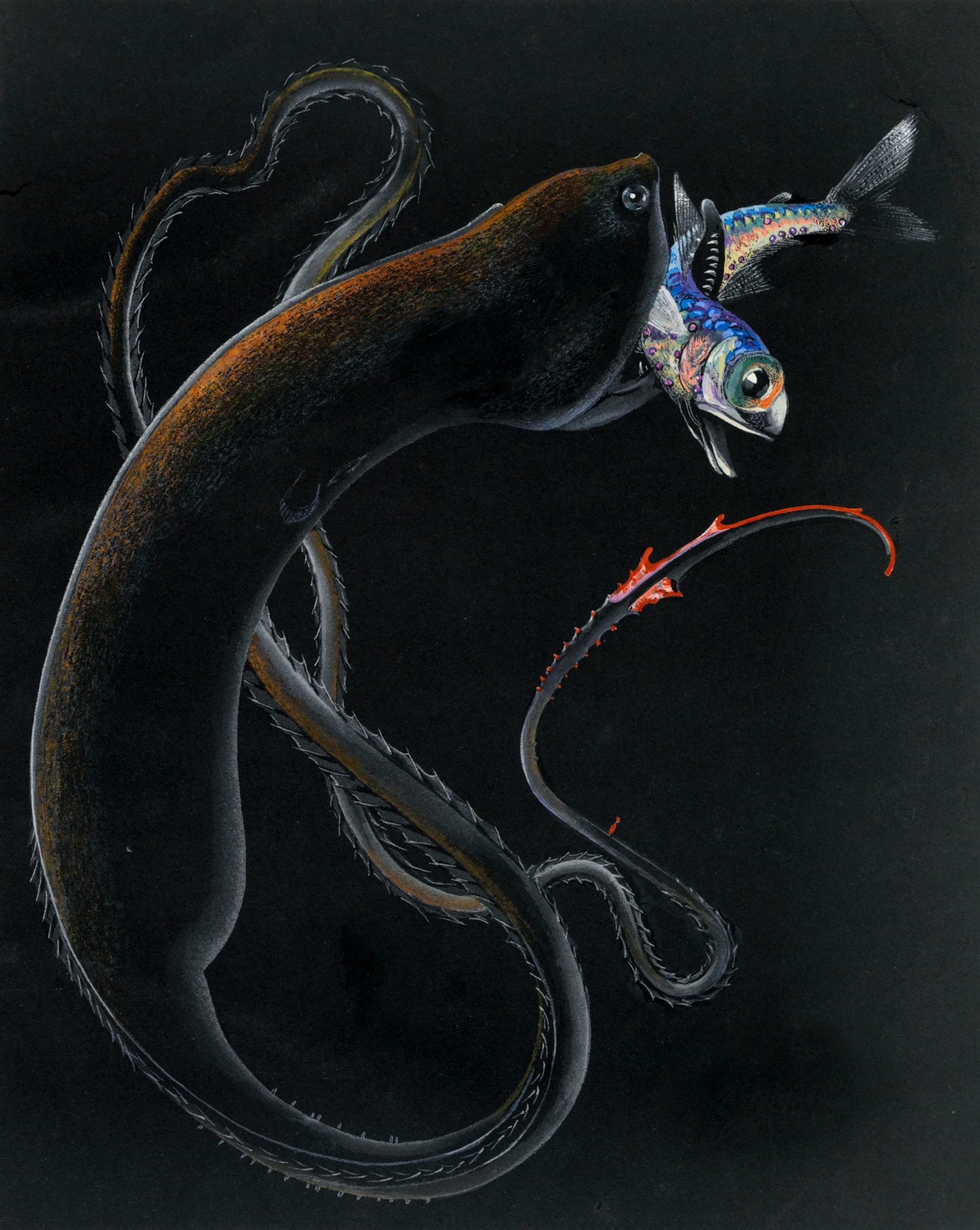

Anable and Beebe bantered throughout and she transcribed Beebe’s observations as he watched the deep-sea life swim by. On the afternoon of June 19, 1930, she transcribed Beebe’s report from a depth of 800 feet: “Little twinkling lights in the distance all the time, pale greenish in color. Eels, 1 dark and 1 light. Big Argyropelecus coming; looks like a worm head on.” She also relayed information to him on depth, time, and weather.

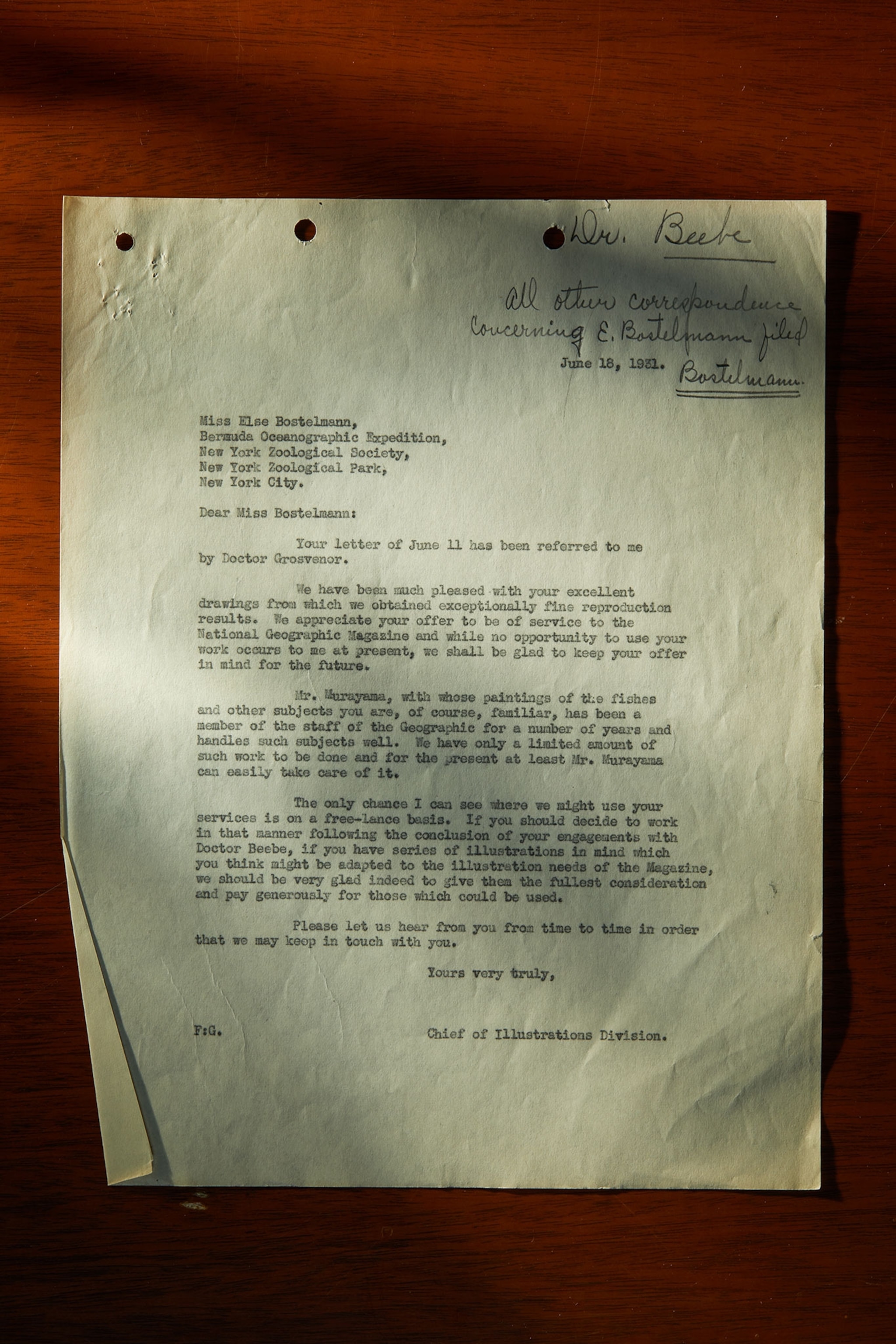

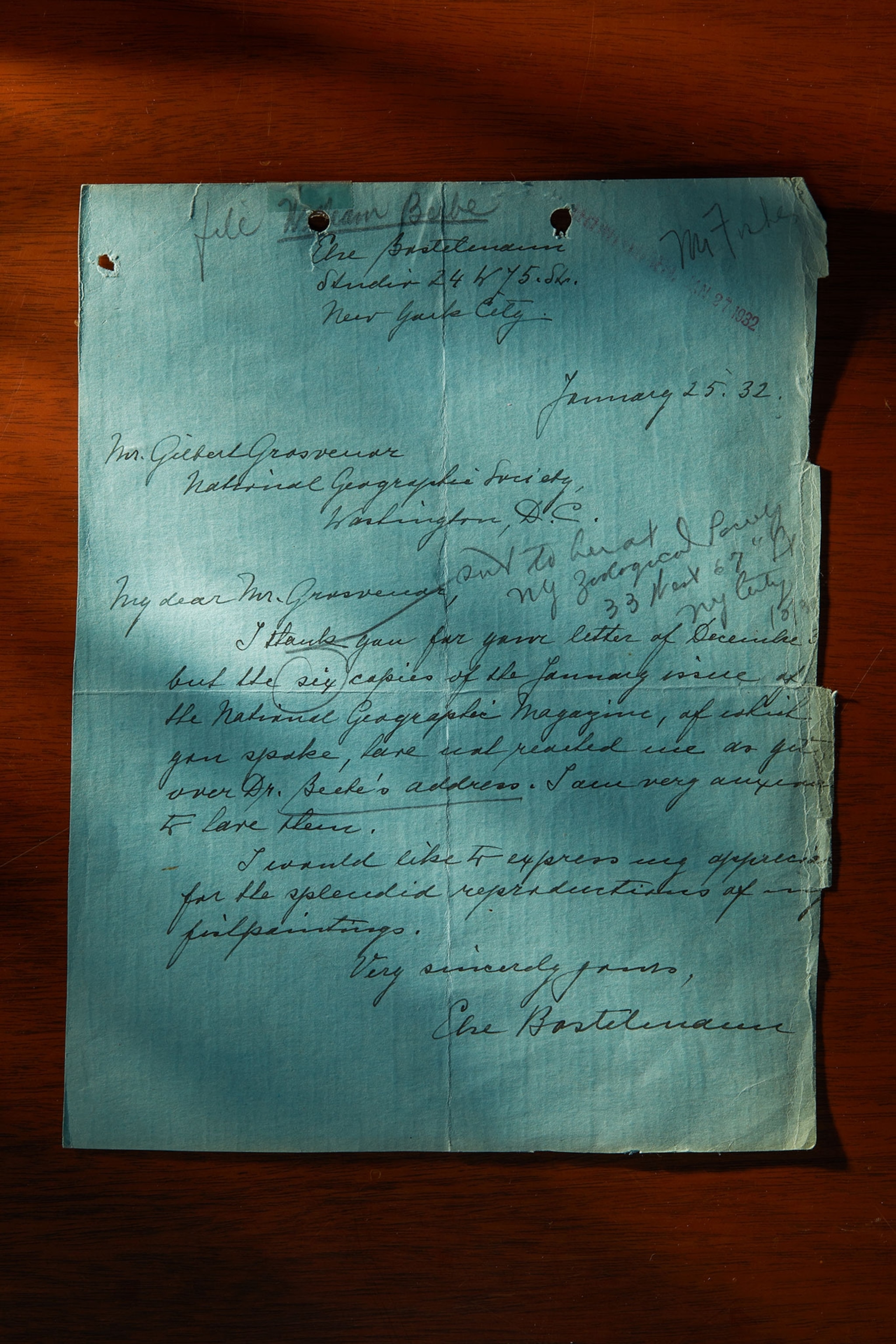

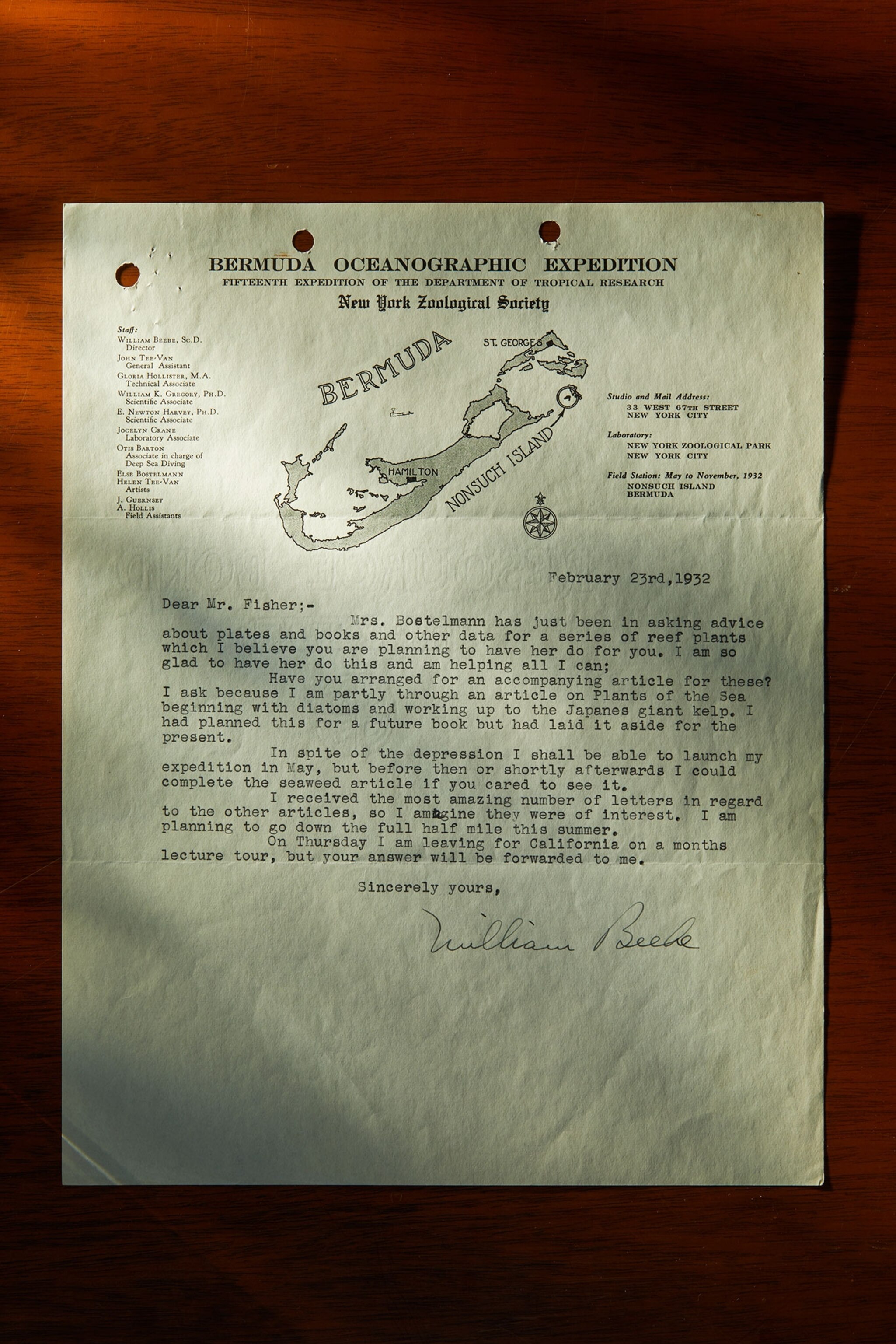

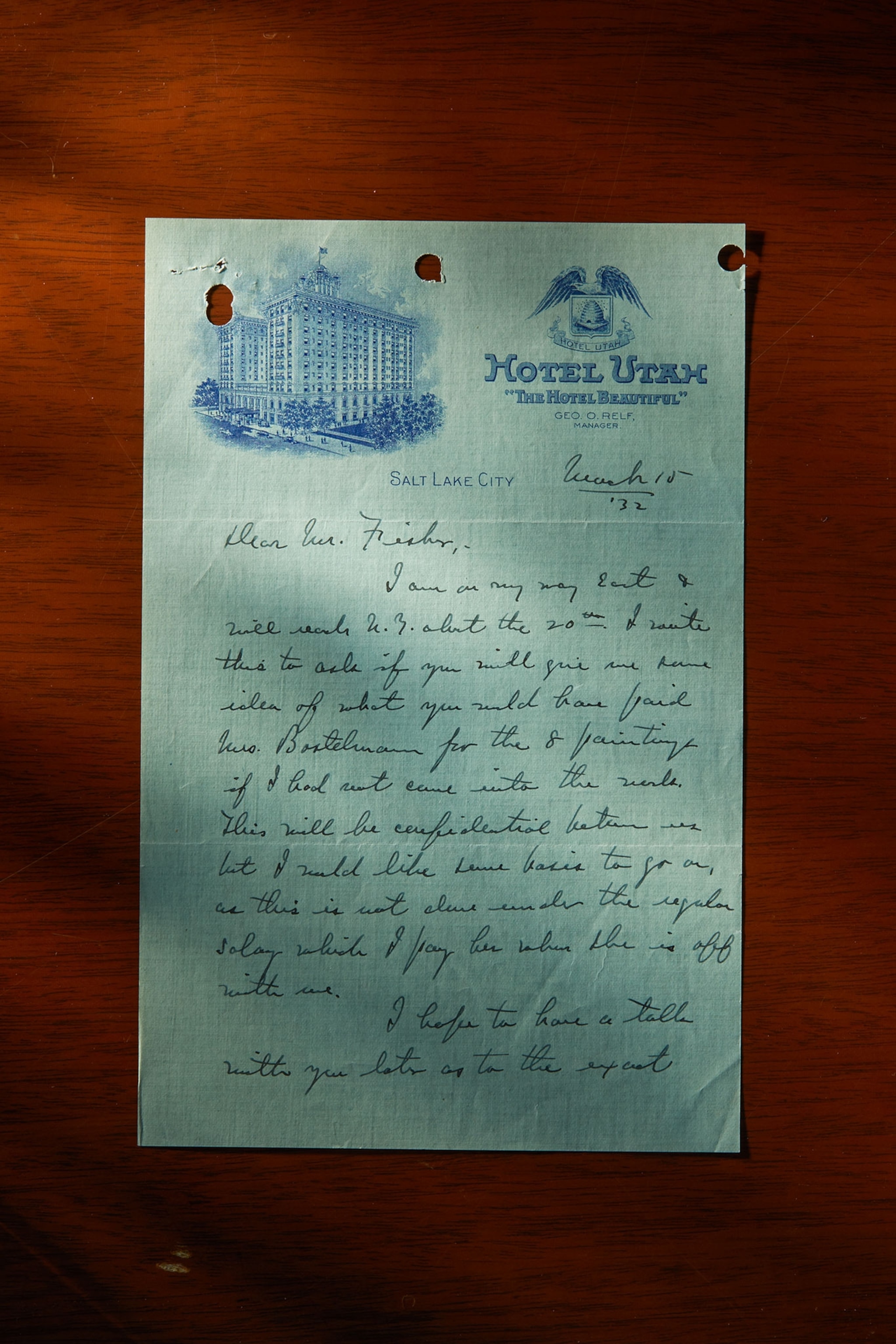

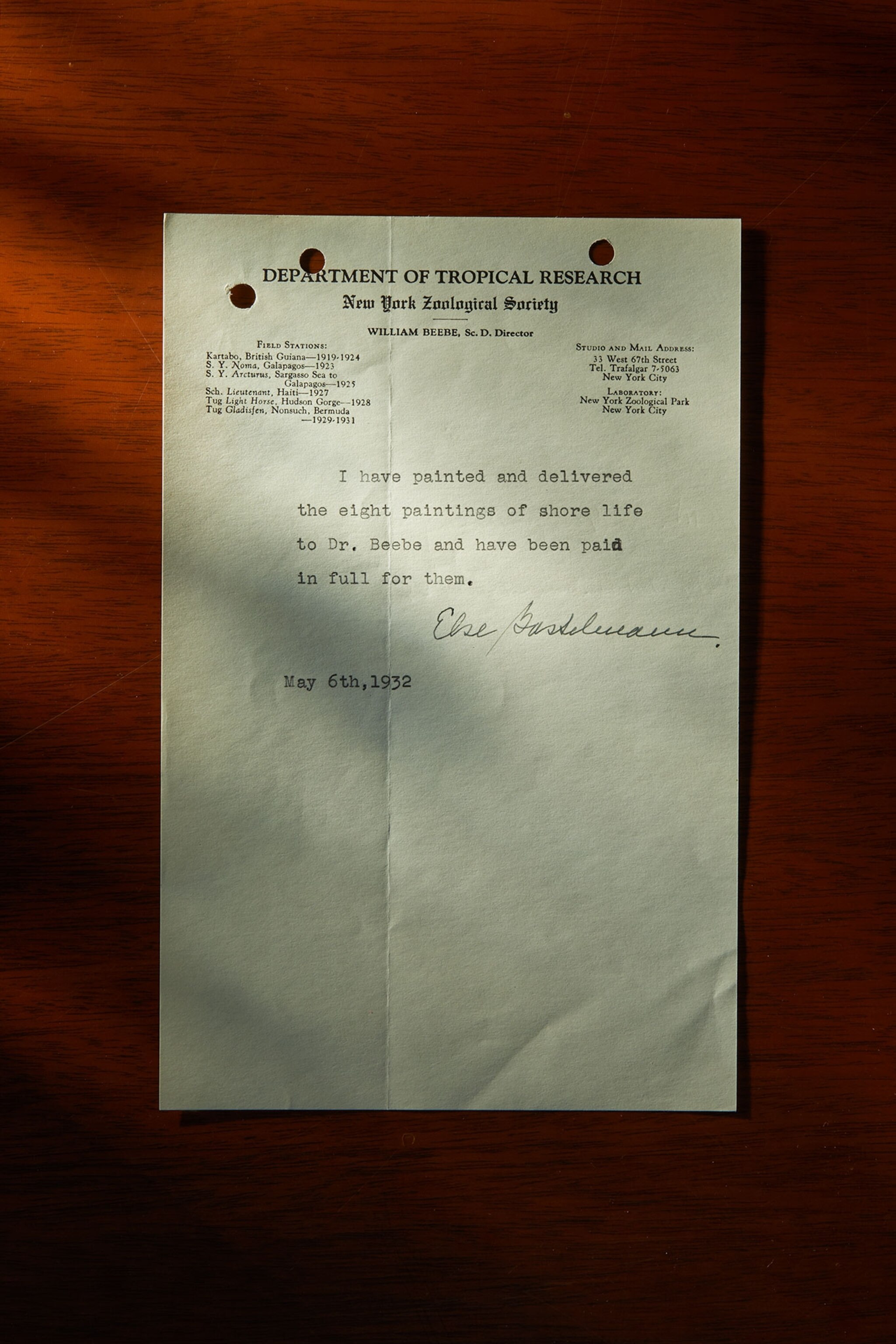

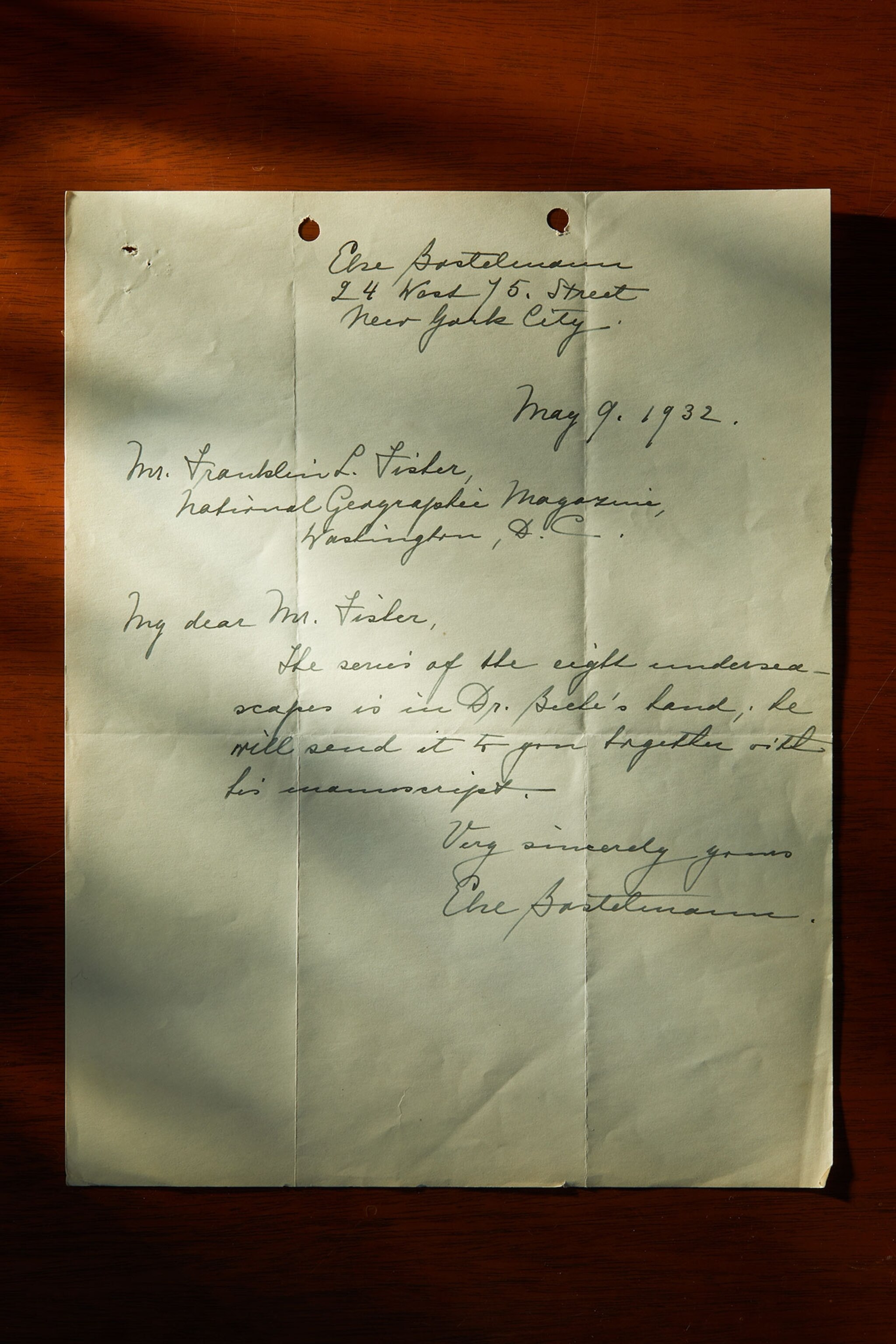

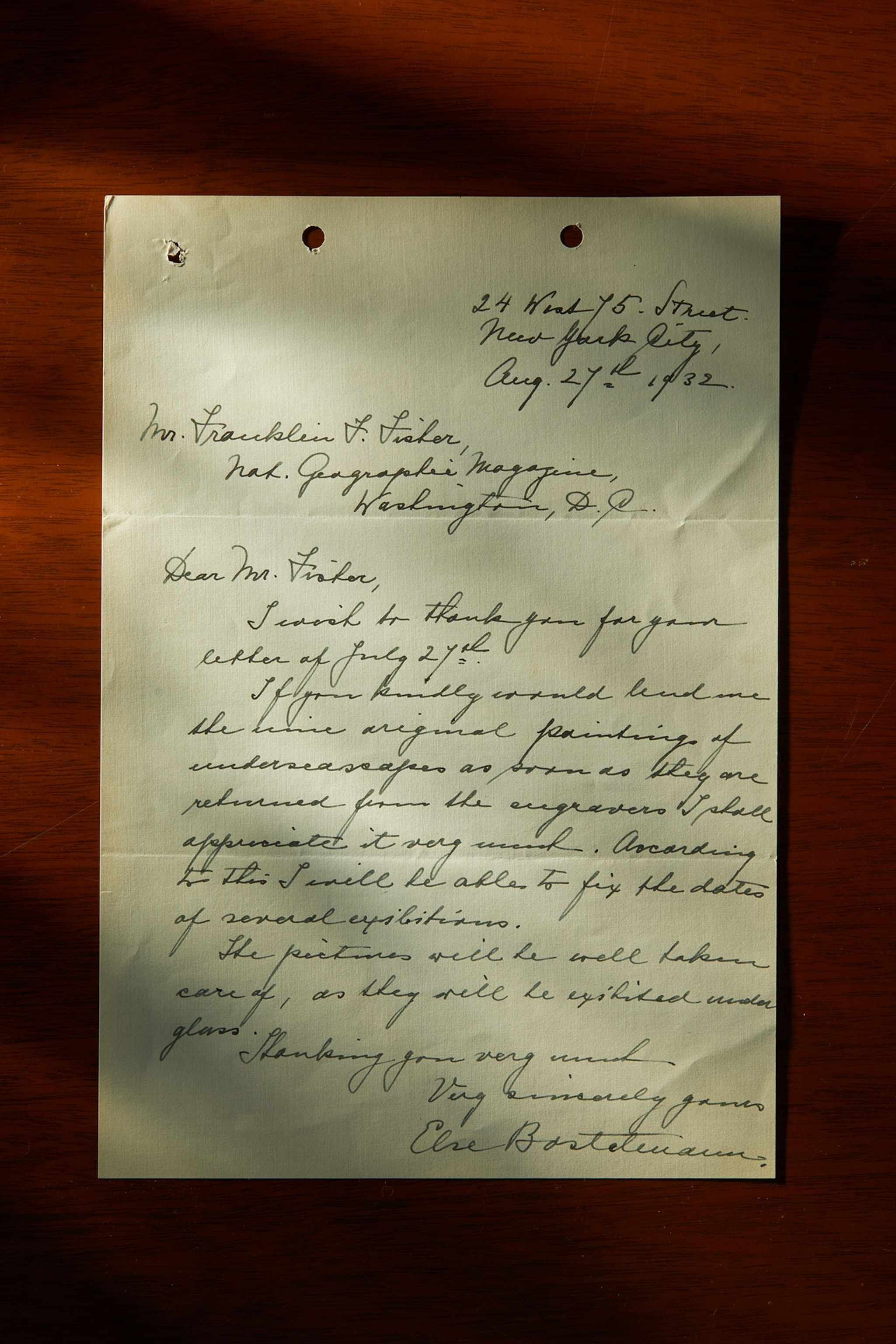

After each dive, Beebe’s sketches and transcribed descriptions would be delivered to Else Bostelmann back at the lab in Bermuda, where she transformed them into dramatic paintings. Though she didn’t watch from inside the bathysphere, she often would put on a diving helmet, tie her brushes to a palette of oil paints, and drag her canvas underwater to paint and find inspiration. The view was a “fairyland,” she wrote later, and the subjects she encountered in the shallows—blue angelfish, red squirrelfish, and others—would “chase or play across my paper, singly or in schools.” Her drawings of fantastical marine life—fish with giant fangs, psychedelic crustaceans, a never-before-seen black-skinned fish—made the expedition come alive in National Geographic.

The Bermudians, wrote Anable, had nicknamed her lab “The House of Magic.” In it, the team dissected and recorded an endless catch of specimens from the deep sea. Many had never before been seen by scientists. “Before us on the laboratory table is an array of transparent, ghost-like forms of what, a short time before, were strange black beings from a mile down,” she wrote in the New York Zoological Society Bulletin newsletter in 1930. By experimenting with dyes, X-rays, and chemical solutions, Anable hoped to learn how these creatures functioned and how they’d adapted to survive in such inhospitable depths.

Beebe was mocked for hiring women, but he stuck by his team. "They really ridiculed him," environmental historian and anthropologist Katherine McLeod told the Smithsonian after helping to curate a 2017 museum exhibit about the expedition. "They called his inclusion of women in these spaces a de-professionalization of the field." His response? That he’d hired his team for their “sound ideas and scientific research.”

Anable and Griffin took turns in the bathysphere as well. Descending 1,208 feet on one of those dives, Anable set a record for the greatest depth reached by a woman.

After the mission ended, Bostelmann continued to illustrate for National Geographic, and Anable led a scientific expedition to what is now Guyana. During World War II she was awarded a medal by the Red Cross for 8,000 hours of volunteer work.

In 1950, Beebe purchased an old house in the jungle on Trinidad and started a butterfly research station—or hotel, as they called it. Griffin joined the team to document and study the “private lives” of butterflies, she wrote in a 1957 story for National Geographic. “We have to furnish not only the comforts of home and excellent food for our insects, but suitable companionship and nursery space as well.” Griffin went on to manage field stations in the Caribbean and conduct a global study on fiddler crabs. When Beebe died in 1962, she replaced him as director of the Department of Tropical Research.

Today, a replica of the bathysphere sits in the lobby of National Geographic’s headquarters in Washington, D.C. More than 90 years since the original was first constructed, it continues to feed the imaginations of explorers.

In an interview in 1991, underwater pioneer Sylvia Earle was asked what inspired her to get into oceanography. She cited Beebe’s tales. “The aquariums of the world, as wonderful and diverse as they are … do not have the sort of creatures that Beebe described from his exploration back in the 1930s,” she said. “And that certainly I found utterly inspiring.”