The Vikings who vanished

New archaeological clues are shedding light on the fate of isolated Norse colonies in Greenland that disappeared during the Middle Ages.

The first time I met Michael Nielsen he had just returned from a summer spent excavating a Viking site in southern Greenland, not far from where he’d lived as a child. Most sites on the island seem to be swiftly disintegrating, their buried artifacts melting into a kind of brown sludge, but this particular wet, marshy site had created what archaeologists call “good preservation conditions.” With a wide grin, he retrieved a small plastic bag containing a tiny wooden horse that fit easily in his massive palm. It was dark and damp, the grain gleaming after many centuries hidden in the earth.

“So cool,” Nielsen said, turning the horse to catch the light in the basement of the Greenland National Museum in the capital, Nuuk. Whoever carved it had gone to great trouble to shape knots into the mane—tiny nubs along a graceful neck. They lent the animal a stunning kind of life.

Many similar horses have been found at sites in Greenland, and as far as anyone can guess, they were children’s toys. Like many other elements of the Viking story, the horses are hazy and hard to place. Were they amulets as well as toys? Did they have some spiritual power? Did the Vikings really knot horses’ manes that way? The horse was still in good shape, and yet it’d been found in a midden, or trash heap. Why?

Nielsen, an archaeologist and a curator at the museum, had no idea. Greenland’s Viking settlers had arrived on the enormous island more than a thousand years before. They’d fared well, then floundered, then vanished, leaving few clues to the utter collapse of their culture here.

“There’s just so much we don’t know about them,” he told me, a smile spreading over his face. “It’s a huge mystery. It’s just super exciting.”

Here is what we do know: Around the year A.D. 1000, a band of Vikings, or Norse as they’re often called, sailed west from Iceland in search of new land and fresh opportunity. They were led by an outlaw named Erik Thorvaldsson, better known to us as Erik the Red, whom the historian Eleanor Barraclough describes as a “hot-tempered serial killer.” Thorvaldsson had “discovered” the island while serving a sentence of exile for murder, and according to medieval records, he’d named the ice-blanketed new territory Grænland, an early experiment in branding. It worked, and slowly the colonies spread through the serpentine fjords of southwestern Greenland, where settlers clung to narrow meadows between the sea and the great ice sheet that dominates the interior. They survived, perhaps even thrived, for half a millennium, carving out large farms, building immense byres and barns, and even raising churches with walls several feet thick.

Then, sometime in the mid-1400s, the Norse colonies in Greenland went dark and their citizens disappeared. Records from the Middle Ages, filled with details on the beginnings of the colonies and stories from their middle years, were silent on the ending. If the Greenlanders all died in some apocalypse—plague, say, or warfare—their cousins in Europe apparently failed to notice. And if they all fled the enormous island, there’s no mention of why or where they went.

(Inside the elaborate world of Viking funerals.)

“The whole thing here is that well-informed people in Europe had no idea what happened to the Greenlanders,” said National Geographic Explorer Thomas McGovern, a professor of archaeology at Hunter College in New York City who’s worked on the so-called Norse problem for more than 40 years. “What this suggests is that they didn’t get out. And the subtext is, they all went extinct.”

Greenland’s Norse have long occupied a special place among history’s list of disappeared peoples, as mysterious as the collapse of the ancestral Puebloans (formerly called the Anasazi) in the American Southwest and the much later disappearance of the first English colonists at Roanoke, in what is now North Carolina. McGovern told me the Norse story looms today in part because it “doesn’t fit with our modern sense of who Vikings were.” It isn’t a made-for-TV tale flush with warriors, raiders, gold, and victory.

Instead, most Norse were simple farmers. Slowly, though, archaeologists including McGovern and Nielsen are assembling a compelling new theory that explains their fate—one that links the end of their world with ours.

When Nielsen was growing up among the fjords of southern Greenland, he didn’t think much of the ruins that lay scattered along the shorelines and hillsides. He understood vaguely that they were ancient barns and houses and churches and that the Norse had built them long ago, probably using horses and sledges to drag the huge stones across the rugged landscape. For Nielsen and most Greenlandic kids he knew, the ruins had little to say. They were just old rock piles, skinned in lichen, feathered with grass, maybe a little haunted. If anything, the lesson they offered was one of failure: They were the relics of people who hadn’t survived in the hard, cold fjords.

Contrary to the violent pop-culture Vikings of our time, the Norse who settled Greenland were the last in a great wave of westbound European settlers who’d carried their culture from the fjords and heathlands of Norway, Denmark, and Sweden to a series of cold and remote outposts: the Orkney Islands, the Faroes, Iceland. In all these settlements, they outlasted centuries of disease and famine, bad weather and bad kings, and today you can find not only their fields and farmhouses but also their modern descendants. A genetic study in 2020, for example, showed that as much as 6 percent of the population of England carries Viking DNA. An earlier study revealed that in northern Britain the number might be several times higher. In Greenland, there is no such legacy. In fact, Viking DNA is found only in old bones.

Some of the oldest of them were discovered in an ancient cemetery circling the remains of what might be the very first church in North America. On a gray day last September I boarded a small boat and headed there, across a broad blue fjord. South of the ruins lies a tiny town called Qassiarsuk—a modern name, given by the Inuit, the inhabitants considered Indigenous to Greenland. The Norse, though, called the place Brattahlið. The view hadn’t changed much since their time. It was late autumn in the fjords. No other boats on the water, no wind or seals or whales. Farmhouses at the far shore were so small and low that it was easy to lose them against the treeless hills and the great gray mountains rising all around. Farther south I could see a small fleet of icebergs gathering, as though to block our escape.

Brattahlið sat at the center of what the Norse called Eystribyggð, the Eastern Settlement, where archaeologists have found the remains of some 500 farms. According to the Sagas of the Icelanders, a compendium of stories written down in the Middle Ages, Brattahlið belonged to Erik the Red, and excavations here have unearthed European skeletons dating back to the turn of the first millennium. This means they were likely among the original settlers, possibly companions of Erik Thorvaldsson himself. The farm eventually grew into one of the largest and most important in Eystribyggð. Here you get a sense of what the settlers accomplished and also what they were up against.

In Old Norse, Brattahlið means “steep slope,” no doubt for the way the hills pour down into the sea. Qassiarsuk, now home to a few dozen shepherds and their families, occupies a flattish shoulder above the water, and farther north lie dozens of ruins. Above the ruins are tundra meadows rising into rock-studded ridges, and beyond these are the mountains, and beyond them is the inland ice: the otherworldly ice sheet nearly two miles thick that covers most of Greenland. Standing at the shore I noticed a sense of pressure, of being trapped between water and ice. I wondered if the Norse felt it too.

Thorvaldsson and his fellow settlers sailed from Iceland to Greenland in what’s known as the Medieval Climate Anomaly (MCA), or Medieval Warm Period. During this time, which began about A.D. 900, temperatures in the North Atlantic region rose higher than they had been in previous decades. While it wasn’t as warm as the world we know today, according to McGovern, the MCA probably decreased sea ice cover and mitigated the violence and frequency of ocean storms. This was all good for the Norse, who loaded their open ships with livestock and lumber, children, wool, and slaves and headed west. Better weather didn’t necessarily make the days-long passage safe: The sagas report that Thorvaldsson led a fleet of 25 ships and only 14 survived the crossing. But the MCA is often credited with easing their migration, helping the settlers find footing in their new world, perhaps giving them a false sense of security.

The Norse raised sheep and cattle, goats and horses, and, in the early years, barley. During the winter, the fjords froze, halting ship traffic, and pastures were buried in snow. Farmers crammed their cattle into byres to protect them from the cold and kept them there until spring. The method appears to have worked, barely. By winter’s end, the animals were often so weak they had to be carried out into the meadows. Farm life was marginal, in other words, despite the relative warmth delivered by the MCA.

(Experience Greenland’s Inuit and Viking sheep farms on this stunning trail.)

The Norse kept at it, though, and in Qassiarsuk you can walk along the foundations of their barns and sheep pens and almost feel the sweat that had gone into their monumental building. The corners of many structures are still almost square, and today’s shepherds use the same pastures. I spent hours hiking through the ruins, shivering under several layers. And yet the landscape never looked cold. Instead, it held a deep summer sheen, and over this lingered the scent of lanolin and fresh-cut hay. You could see why Thorvaldsson named it Greenland, even if he knew summer’s color would never last.

At one point I climbed up through meadows, past dozing sheep, to a hilltop overlooking the fjord. The clouds parted, sunlight peeked through. I unzipped my jacket. In the distance a cruise ship appeared, and inflatable rafts full of tourists in bright red jackets began racing toward shore. In an hour they would temporarily double or triple the population of Qassiarsuk—all coming, as I had, to be haunted among the ruins. I sat back and tried to enjoy a few more minutes of bright solitude. But then the clouds closed again and the warmth ran out, just as it had long ago for the Norse.

Cold was among the first culprits to be blamed for the Viking colonies’ collapse. In the early 1700s, a Norwegian missionary named Hans Egede sailed to Greenland hoping to find Vikings and, if necessary, convert them to Lutheranism. By that point, no one in Europe had heard anything from the Greenlanders for some 300 years. They had missed most of the Renaissance, the Enlightenment, and the Protestant Reformation, and Egede may have worried that during the long silence they had fallen back on their ancient pagan ways. When he reached Greenland’s southern fjords in 1721, Egede fully expected to meet Norse. But there were none, not a single savable soul.

Egede visited their ruins, possibly including Brattahlið, and he somehow managed to communicate with the Inuit, who had moved down from northern latitudes into spaces once occupied by the Norse. Egede later speculated that either the Inuit killed off the Norse (though he might have had trouble believing that people he described as “savage” could do such a thing) or the cold did them in.

Egede was exploring and writing during what we now call the Little Ice Age (LIA), a period of dramatic cooling that followed the Medieval Climate Anomaly. It began in the early 1300s and lasted about 500 years, and in Europe the LIA ushered in colder, wetter weather that has been blamed for widespread destruction and hardship. Famines, economic ruin, political upheaval, and possibly even the onset of the witch-burning hysteria that surged across the continent have all been linked to dropping temperatures and the follow-on effects of an unready world.

For the Greenlanders, the climate seems to have changed quickly, with the cold deepening toward the end of their era. Jette Arneborg, who was for many years senior researcher at the National Museum of Denmark in Copenhagen, told me that in the 1970s scholars began braiding together data on the LIA with notions of overexploitation. Their theory: The Norse had exhausted the natural resources around them. They’d overgrazed their livestock, felled the fjords’ meager trees, and otherwise undermined their own farming efforts. They also seemed to ignore local foods such as fish and marine mammals. All of this made Norse life fragile. And when the cold came, it shoved many of them over the edge into starvation.

McGovern summarized it this way: “The old story was, ‘These poor, dumb Norsemen go up there and they’re all maladapted, and they all died when it got cold.’ ”

But slowly, Arneborg explained, climate determinism has yielded to a more nuanced view, as more data, paired with newly applied scientific disciplines—including genetics, climatology, and even economics—have been brought to bear on the Norse problem.

“It’s interesting to see how the theories have changed,” Arneborg said. “Now we know the climate changed very rapidly, but it wasn’t just that.”

Arneborg herself helped discover one illuminating detail. In 2012, she and colleagues published the results of an isotopic analysis of Norse skeletons, including some unearthed at Brattahlið, that showed a profound shift in diet across decades from terrestrial mammals to marine ones. It meant that while early colonists depended heavily on their own livestock, later generations consumed far more seals. Her finding indicated not just a growing dependence on the sea but also a discernible shift in which Norse farmers turned more toward hunting and fishing.

Christian E.K. Madsen, an archaeologist and researcher at the National Museum of Denmark, said that Arneborg and her colleagues had helped reverse long-held assumptions about the Norse. “They are essentially hunters that farm a bit,” he said. “As opposed to farmers who hunt a little.”

The shift in diet also loosely paralleled the change in climate as the LIA began. Taken together, these threads of evidence effectively scuttled old notions that the Norse committed some kind of ecological suicide or that they simply couldn’t handle the cold. Instead, scientists now believe the Norse were very resilient and flexible, handling every new problem the changing world could throw at them—for a while.

“I think the development over the last decade is how complex that transition from MCA to Little Ice Age is,” Madsen told me. “Generally speaking, we can see now that the brunt of the Little Ice Age didn’t occur until after the Norse were gone. What seems to be fairly certain is this change to a more unstable environment, kind of like we have now.”

The old story was, “These poor, dumb Norsemen go up there and they’re all maladapted, and they all died when it got cold.”Thomas McGovern, professor of archaeology, Hunter College

When I arrived in Nuuk in September to meet Michael Nielsen at the national museum, warships could be seen cruising up the fjord to the north: a Danish-led military exercise that international media described as a show of force aimed partly at Russia, and partly at the United States after President Donald Trump’s remarks about buying Greenland or somehow pulling it further under American influence.

Greenland is a self-governing part of the Kingdom of Denmark, with a population composed mostly of Inuit—descendants of the people who survived here after the Norse vanished. Nielsen, a Greenlander of mixed Inuit and Danish heritage, told me he wasn’t too bothered by Trump’s talk or Denmark’s nervous response. “It’s serious for us,” he said. “But it’s actually good because it forced the Danes to pay attention.”

In an attic at the back of the museum, Nielsen moved slowly as we pored over the artifacts we’d gathered from the display cases. He’d broken his left arm several weeks earlier while searching for old grave sites in a boulder field down south.

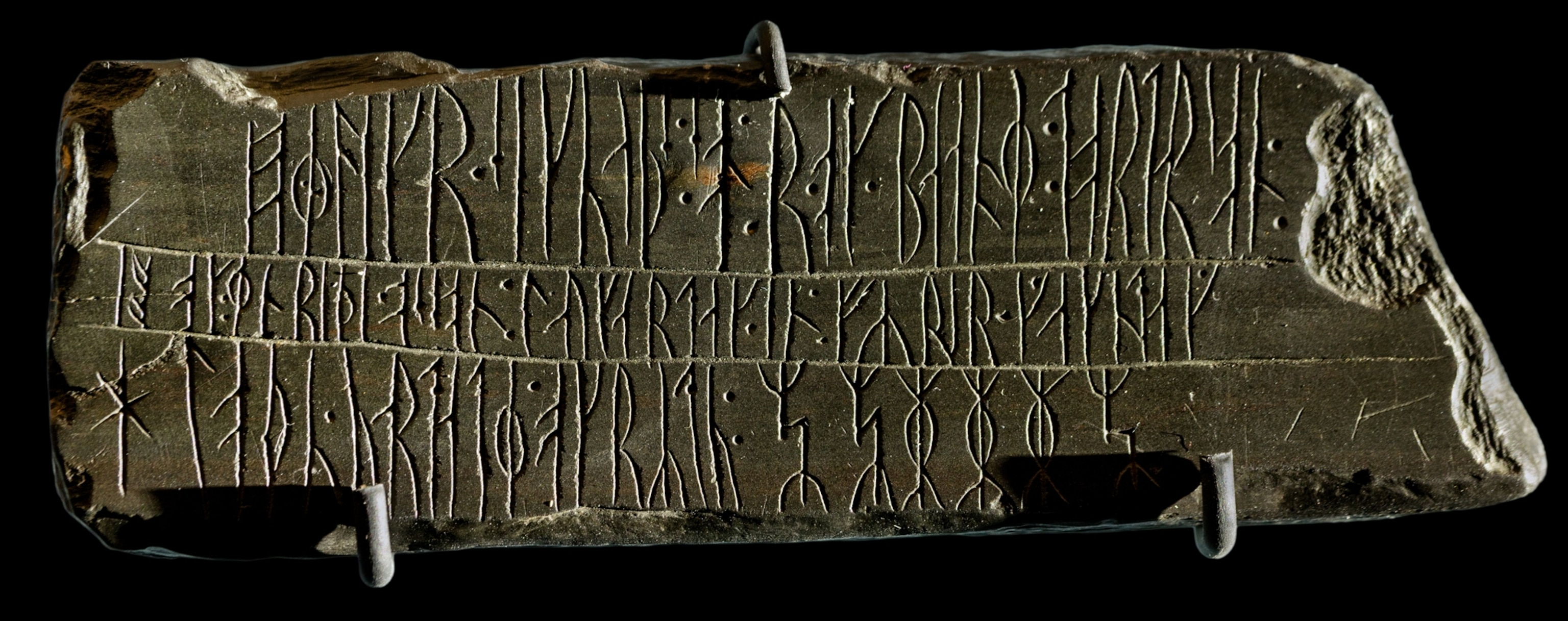

Among wooden horses that might have been children’s toys, rune sticks with apocryphal inscriptions, and a soft lock of braided hair was a piece of a walrus skull. Most of it was missing: no eye sockets, no jaws, just a wedgelike chunk of the face. A large hole showed where the animal’s airway had once been, and to the right of this was a cavity where one of the enormous tusks had grown. Looking closely, we could see chisel marks in the bone, evidence that the tusk had been painstakingly removed by a Norse hunter.

Nielsen pressed a finger into the socket and said, “White gold.”

Recent research into the Norse enigma now focuses on walruses and the importance of their tusks—the white gold. In this latest theory, the Norse migrated to Greenland not to farm the fjords so much as to monopolize the North Atlantic trade in ivory. At the time, tusks were used for making ornate chess pieces, crucifixes, knife handles, and other luxury objects coveted by rich Europeans. Walrus populations around Iceland had, by the time of Erik the Red’s voyage, been nearly hunted out, and so Greenland’s animals became highly prized. Tusks were shipped east toward the continent, in exchange for European lumber, iron, and other goods. For a while it seems to have made some Greenlanders relatively wealthy. According to James Barrett, an archaeologist at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology, Greenlanders were even able to use tusks to pay tithes that would eventually reach the church in Rome.

“We see the walrus tusk is crucial,” Madsen said. “Otherwise no one would care about this outback population at the end of the world.”

Walruses, though, did not live near the Eastern Settlement or even the much smaller Western Settlement, Vestribyggð, which existed in the area around present-day Nuuk. To find the animals, the Norse needed to travel farther north, beyond the Arctic Circle. The journeys were dangerous, made in open boats into waters clotted with pack ice. The walruses themselves were dangerous too—3,000 pounds of bone-cracking, boat-crushing beast. But the dangers, the distance, and even the onset of the Little Ice Age did not deter the Norse.

A study published in 2024 used DNA to trace walrus tusk artifacts back to the areas where the animals had originally lived. It showed that the Norse probably traveled deeper into the north than previously thought, perhaps all the way into the high Arctic and even into parts of Arctic Canada—journeys of hundreds or even thousands of miles. Such trips, the paper noted, would have put many lives at stake. They also would have consumed precious resources and possibly threatened the stability of the entire society. And yet the hunts went on because tusks were the Greenlanders’ cash crop, their lifeline to Europe, the commodity that kept ships coming.

Sometime in the 1200s, the Greenlanders’ “white gold” monopoly began to crumble. Elephant tusks imported from Africa were entering Europe’s luxury market, putting pressure on the Norse economy. But Arneborg told me that the world had also moved on, leaving the Norse adrift at the fringes.

“When they settled, it was in the last part of the Viking age, when trade systems depended on valuable objects,” Arneborg said. “But by the medieval period, the whole economic system of Europe had changed. Suddenly you have another system where you trade foodstuff, so all of your valuables aren’t that valuable anymore.”

Still the Norse kept pushing into the Arctic, even as the cooling climate made travel riskier and the sea less predictable. In the later phase of the Norse period, walrus tusks were getting smaller and smaller, and were being taken from animals that lived ever farther away, according to a study by researchers in the United Kingdom, Ireland, and Norway. While the Norse surely recognized what was happening, they likely felt trapped.

If they couldn’t trade tusks, what else did they have? No forests, no iron, no wheat or vegetables. Their resources seem to have been limited to seal skins and seal oil, as well as the hides of other animals. When the tusk trade bottomed out, Arneborg said, European ships probably visited Greenland less and less often, just as the changing climate made the voyage more dangerous. By the middle of the 14th century, things looked pretty grim for the Greenlanders, and they almost certainly saw the writing on the wall. Archaeologists believe that the Western Settlement had collapsed by the late 1300s. At about the same time, the bubonic plague burned through Europe, killing tens of millions. And in Norway—the main trading partner for the Greenland colonies—estimates suggest that more than half the population died. There’s no evidence yet that plague came to Greenland, but large-scale epidemics, possibly of plague, did ravage Iceland in the 1400s.

There is one more historical detail that archaeologists aren’t quite sure how to square. By the end of the colonial period, the Inuit had moved into southern Greenland. In some areas they were living very near to Norse settlements, virtually becoming their neighbors. No one knows how the two groups interacted. Some old European records—as well as some Inuit oral traditions—tell of fighting, though no archaeological evidence of conflict has ever been found. Still, researchers I spoke to said it was difficult to imagine relations weren’t tense. Medieval records tell how the Norse called the Inuit Skraelings, which may have meant something like “barbarians” or “weaklings.” In other words, it probably wasn’t said kindly.

What’s perhaps most interesting about their relations is that the Inuit offered a model for how to survive in a changing, unpredictable world. Researchers believe the Thule Inuit crossed over from what is now Canada into northern Greenland sometime around the year A.D. 1200, several generations after the Norse arrived on the southwestern shore. The Inuit were nomads, following seals, walruses, caribou, whales, and other creatures through the seasons and across the land and sea. They were descended from cultural traditions developed over several thousand years, in some of the coldest, harshest terrain on Earth. Yet while the Norse made some similar adaptations (eating more seals, for example), there was apparently a cultural point past which they would not go. In other words, the Norse refused to become more like the Inuit or adopt a more nomadic lifestyle, even if it might have saved them.

Many experts I interviewed believe the Norse probably never considered such a cultural transformation. They were too conservative, too tethered to their own sense of European identity. Perhaps their reluctance was rooted in racism or religion. It’s also possible that most of them simply escaped Greenland before such radical choices became necessary.

The last recorded voyage between Norway and Greenland occurred in 1410. Some of the last news out of the colonies described a witch burning around 1406 and a wedding in 1408. What these mundane dispatches don’t mention is any kind of world-ending calamity—no plague, no slaughter, no starvation.

After this, the Norse Greenlanders disappear from the historical record. Archaeologists believe that by 1450 Eystribyggð was empty, everyone dead or gone. How the Vikings may have gotten off the island is still an open question, like so much else about their story.

Madsen told me that in the waning days of the colonies young people probably jumped onto any ship they could and begged passage to somewhere, anywhere else. But, Arneborg noted, “we don’t have any clues at all.”

What we know is that their world was growing darker, colder, and more chaotic. The Inuit were pressing in at the edges of the colonies. The Viking population was almost certainly in decline.

“Perhaps you have some old people surviving on a few farms,” Arneborg said. “But what about everyone else? Imagine you’re sitting in Greenland, and you don’t have a ship yourself. You’re just waiting for the ships to come from Norway. And then, in the end, they don’t.”

(Facts vs. fiction: How the real Vikings compared to the brutal warriors of lore.)