Scientists find oldest direct evidence of whaling in a place they never suspected

Once dismissed as sticks and forgotten in a museum, the 5,000-year-old tools show prehistoric people hunted whales far from the Arctic.

Ancient "sticks" nearly forgotten in a Brazilian museum may actually be 5,000-year-old harpoons used to hunt whales, seals, and sharks, researchers reported last week. If confirmed, the discovery may be the oldest direct evidence of whale hunting yet found, pushing back the timeline for direct evidence of whaling by more than 1,000 years.

The finding, published in Nature Communications, suggests that the marine hunting practice was not limited to just the cold waters of the near-Arctic but also occurred off the warm coasts of South America during prehistoric times. The harpoons, which were fashioned from whale bones, demonstrate the dangers early hunters in present-day Brazil braved to bring home a hearty meal.

Hunting a whale with a bone harpoon from a hollowed-out log canoe "would have been risky, but it's a lot of food," says Krista McGrath, a biomolecular archaeologist at the Autonomous University of Barcelona and lead author of the study. Local people likely gathered to devour as much meat as possible from a single whale kill, McGrath says, while much of the rest would have been preserved using oil from the carcass or by drying it.

"You can imagine a big feast where everyone eats a lot of meat and blubber, and at the same time they collect oil," says co-author André Carlo Colonese, a biomolecular and environmental archaeologist at the same university. "You can store the oil for a very long time, you can use it as fuel, and then you have all the bones… a whale is very valuable."

Hidden harpoons

A few years ago, Colonese was at the Museu Arqueológico de Sambaqui de Joinville in Babitonga Bay on the coast of southern Brazil, when he saw the harpoons.

At the time, they were described only as sticks recovered from an ancient pile of shells called a sambaqui. These massive mounds dot this coastal region and were created by prehistoric people from the shells of shellfish they ate. Roadbuilders in the 1940's and 1950's dug into the sambaquis for lime to create concrete and uncovered thousands of artifacts hidden inside. The bounty, which included the sticks and many sambaqui figurines, was eventually brought to the museum. For decades, the sticks were left in the collections until Colonese identified them as harpoons.

(A shaman’s fight to save Indonesia’s last subsistence whale hunters)

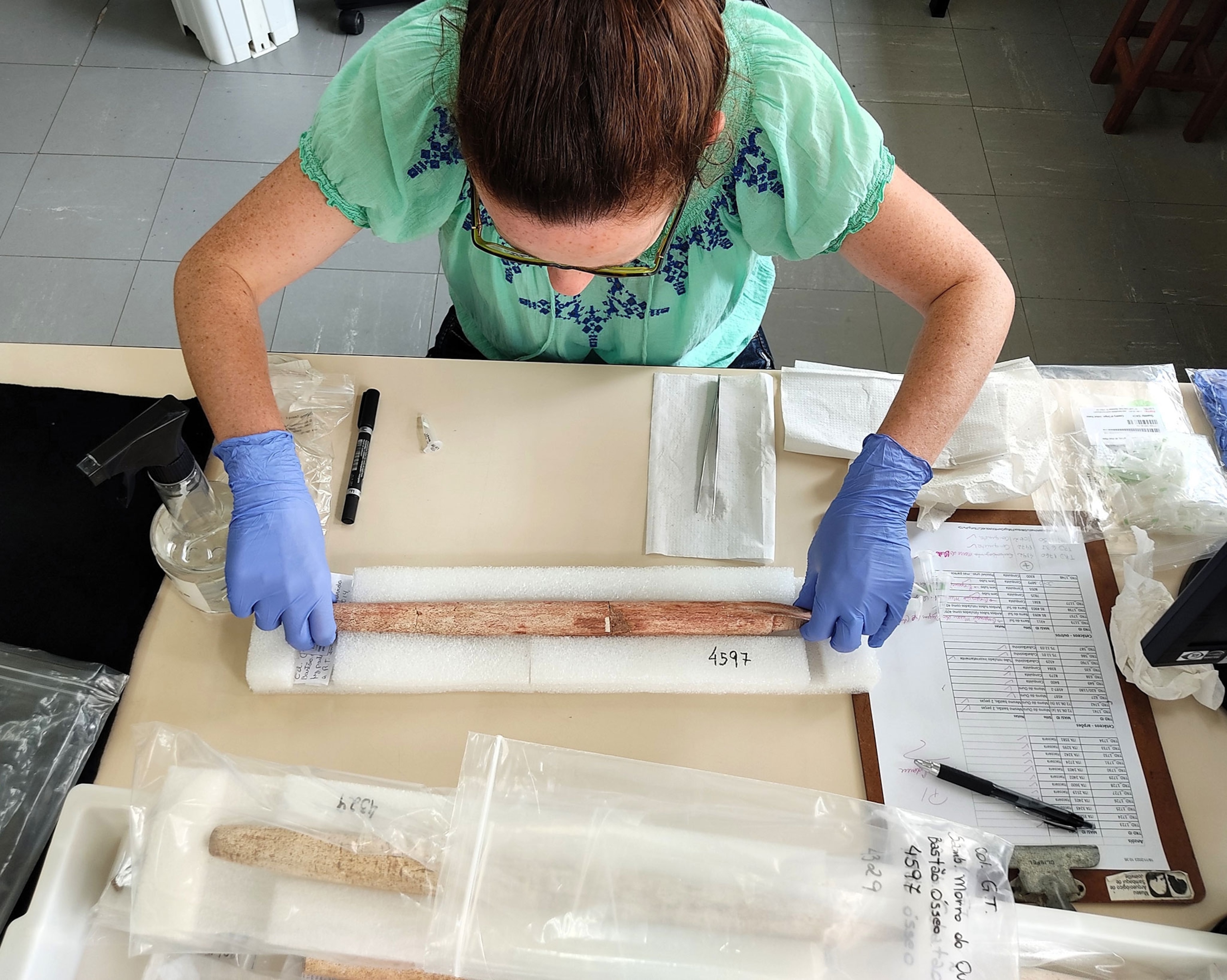

The harpoons were originally made of both wood and bone. But the wood rotted away long ago, and only the bone foreshafts remain. The researchers suggest the foreshafts would have been barbed and connected by a cord to an inflated bladder or a buoyant piece of wood.

The barbed point would then be fitted into a loose whale bone or wooden socket on a shaft so that it separated after harpooning the whale. The wood or bladder would have prevented the whale from diving, allowing the hunters to spear it on the surface. Later whale hunters also used similar tactics to take down the leviathans.

The researchers also identified which whales the bone harpoons were from. They found they were carved from two different species—southern right whales and humpback whales. The bones were then radiocarbon dated to between 4,710 and 4,970 years ago.

Warm water whaling

Some older spears called "harpoons" have been found in parts of Europe and the far south of South America, but it's thought they were not used for whale hunting. Whale bones and bone tools have also been found in South America before, but scientists thought ancient people scavenged them from stranded whales.

The harpoons from Babitonga Bay, however, are exceptionally large—some are almost two feet long—and they seem designed for taking down large sea animals, especially whales that would have sheltered in the region's many coastal inlets to calve, McGrath says.

(This digital graphic novel takes you on an Indonesian whale hunt)

Babitonga Bay is far from the frigid waters where prehistoric whalers were thought to hunt. The finds suggest that prehistoric people were actively hunting whales along the subtropical and temperate coasts of Brazil, according to Colonese.

"We need to have an open mind and to look at these regions of the world for evidence of whaling,” he says, “not just in the colder waters of the northern hemisphere."