‘I want to be part of the change’: Why thousands are demanding racial justice

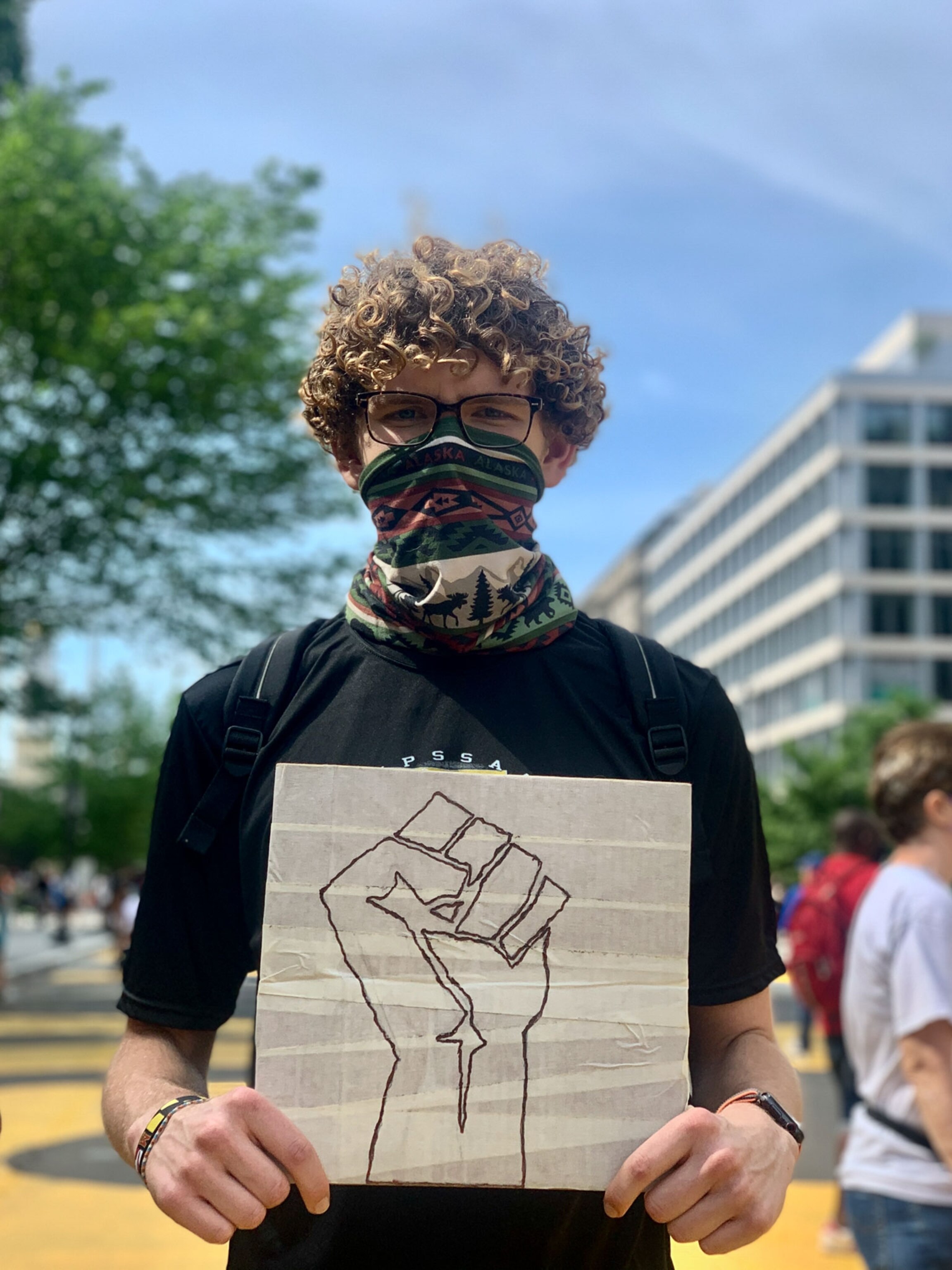

Protesters gathered in Washington, D.C., to call for an end to the "pandemic" of racism. These are some of their stories.

The week began with anguished shouts and chants, heavily armed police and fumes of tear gas in the area around Washington, D.C.’s Lafayette Square Park.

On Saturday, almost as many people pushing baby strollers as carrying signs streamed into that same area to protest the death of George Floyd, who died violently on Memorial Day as a Minneapolis police officer kneeled on his neck for nearly nine minutes.

Most major cities in the United States reported large demonstrations, and many were organized in small-town America as well. Around the world people joined in largely peaceful protests sparked by the death of Floyd, in a dramatic push to elevate the issue of police brutality and what has been characterized as a “pandemic” of racism and white supremacy. From London to Nairobi, Berlin to Tokyo, Melbourne to Beijing, people marched to major public venues where speeches, songs and silent demonstrations on bended knee were designed to send a message: Police brutality, racial violence and racism must stop.

I want the world to get better because I’m bringing a son into this world, and I don’t want my son getting shot by the police. Black lives do matter.Janiya Ware

The worldwide protests Saturday occurred one day after what would have been the 27th birthday of Breonna Taylor, the African American emergency medical technician who was killed in her Louisville, Kentucky, home in March by police officers who forcibly entered the wrong apartment while executing a warrant.

News of her death, along with other racially motivated killings in the U.S., such as that of jogger Ahmaud Arbery in Georgia in February, culminated in a spasm of violence, fires and lootings that erupted shortly after Floyd’s death. As America’s racial tensions were telegraphed around the world, conversations about the need to dismantle white supremacy, defund police departments and toughen laws about race-related crimes rose to the top of national discourse. (Related: Read about the long history of racial violence against black Americans.)

By June 6, it seemed the need to bear witness and register dissent was a motivating factor for protesters around the world. Thousands gathered in the 16th Street corridor, renamed Black Lives Matter Plaza by D.C. Mayor Muriel Bowser and adorned in gigantic yellow block letters, that ended right in front of the church where President Donald Trump hoisted a bible before flashing cameras.

In fact, Saturday was Messiah McKinley’s 12th birthday, and his parents Vondell and Yamica wanted to bring him and his 10-year-old brother Yeshua to Black Lives Matter Plaza because they face a parenting dilemma shared by many African American parents.

“I want them to be strong and independent, and know how to express themselves clearly,” Vondell McKinley says. “I want them to move through the world confident, and not have any fear about what they believe. But they also need to understand the reality of life, and how sometimes, they have to be aware that interacting with the police means they have to think twice about what they say.” (Related: "For Black Motorists, a Never-Ending Fear of Being Stopped.")

This has been in the making for centuries. It feels ancestral ... we’ve got ancestors behind us in this.Joi Donaldson

McKinley worries about what the future holds for his sons, but he also sees reason for optimism. “They learned a lot today. This was the first time they had ever been in a crowd that big, and I think the signs and the way people were interacting had an impact on them. They needed to be there.”

By noon, the crowd at the base of the Lincoln Memorial was chanting the names of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Ahmaud Arbery and many others through bullhorns. Verses of spirituals like “Wade in the Water” and “Lift Ev’ry Voice and Sing” echoed along the mall, in a steadily growing crowd near the reflecting pool. By evening, an estimated 10,000 people passed peacefully through major thoroughfares in D.C. leading to the Capitol and farther along 16th Street to Malcolm X Park.

For some, the events evoked strong memories of similar marches. Carol Williams, 61, moved back to D.C. from Gainesville, Florida, last December. She came out on Saturday, wearing a Malcolm X t-shirt, for her four children, 20 grandchildren and one great-grandchild. “I’ve been walking and fighting and praying since 1972.”

Williams says her older sister Faye Williams used to own the popular Sisterspace and Books store on U Street before gentrification made it too expensive to keep the doors open. “I’m still fighting this racism for the people. Sometimes it feels like nothing has changed, but we gon’ change it this year. I love the white people who care about us, but I don’t bite my tongue and the Lord knows my heart, and we gon’ stop this today.”

I am so happy to be alive at this time to be a part of this great movement. It’s 'we the people'. Not 'them the people'. Now it’s our turn.Maria Modlin aka "Yaya"

And as in many other cities in America, the crowds consisted of just as many white people as black and brown marchers.

Ben and Sarah Peisch came with son Avery, 5, and daughters Noelle, 3, Naomi, 2 and 8-month-old Audrey. The journey from their Columbia Heights neighborhood to the White House posed a different type of challenge.

Avery attends a diverse public school kindergarten, and the Peisches have many friends who are people of color. But it’s hard to explain the protests surrounding the death of George Floyd to a little boy looking for heroes.

“He’s very much into the concept of ‘good guys and bad guys,’” Ben Peisch says. “Trying to explain to him that sometimes people are treated badly, but it’s not because they did bad things, is hard. That’s what we’ve been working on.” (Related: Learn how to talk to your kids about race.)

But the Peisches have brought their children to several other marches and vigils since Floyd's death, and they intend to continue the tradition.

"We both have backgrounds in education, and we want to be sure to expose them to causes like social justice," Ben Peisch says. We want to 'bake' advocacy into their DNA.”

But for many older white Americans, their presence was the first step toward publicly acknowledging the severity of America’s racial crisis and lending their support.

As Trina Wolf sat on the curb in front of St. John’s Church near the White House, she held a sign bearing the phrase “I Will Never Understand, But I Stand.” Wolf also carried homemade face masks she’s been making since the COVID-19 outbreak began, and which she was giving away to fellow marchers.

The 58-year-old Michigan native has attended many marches for social justice in Washington, D.C., but says this one feels different. “I just think it’s terrible what’s going on in our country and what has gone on forever. I just think that as a white person, I need to be here.”

Wolf says she has several right-wing family members and friends who are good people, but who dismiss talk about marches and demonstrations and racial injustice.

“They frankly think that all the bad news is just fake. They haven’t felt it, they don’t understand it, and I don’t think people that are white can ever really understand how it feels. But we need to let the world know that we support people who do live these things every day.”