Will U.S. schools follow the big leagues and leave behind Native American mascots?

Even as professional teams shed “Indian” themed mascots or names, more than 1,000 K-12 schools continue to use Native “themed” logos.

Often, the most die-hard supporters of Native American appropriation in team names and mascots argue that the names, mascots, and caricatures are meant to be an honor. They argue that names such as Major League Baseball’s Atlanta Braves, the National Football League’s Kansas City Chiefs, or the college football powerhouse Florida State Seminoles are all intended to extol the bravery, fighting spirits, or prowess of the American Indian. They further argue that efforts to cancel the names and images are nothing more than political correctness masquerading as morality.

However, Native American activists reject this notion on its face, arguing that all stereotypes are inevitably steeped in bias and are harmful—even those that attempt to romanticize an image or appear to be steeped in good intentions.

So even as professional sports teams have begun to shed “Indian” themed mascots or team names—such as the NFL’s Washington Redskins that changed its name to the Washington Football Team in 2020, or the Cleveland Indians, which starting next baseball season will be called the Cleveland Guardians—the fight of Native American elders and social justice advocates remains far from finished.

As millions of American school children returned to classrooms or virtual learning this month, many returned to schools that use “Indian” names. More than 1,000 K-12 schools continue to use Native “themed” mascots or names, including Redskins, Indians, or Chiefs.

Clyde Bellecourt, a noted Native American activist and the last surviving co-founder of the American Indian Movement (AIM), was recently visiting with his grandchildren when he offered his opinion on the decision of Cleveland’s professional baseball team to change its name from the Cleveland Indians to the Cleveland Guardians.

“No, I’m not celebrating the business decision of the Cleveland team to change that derogatory name,” Bellecourt, 85, said from his home near Minneapolis, Minnesota.

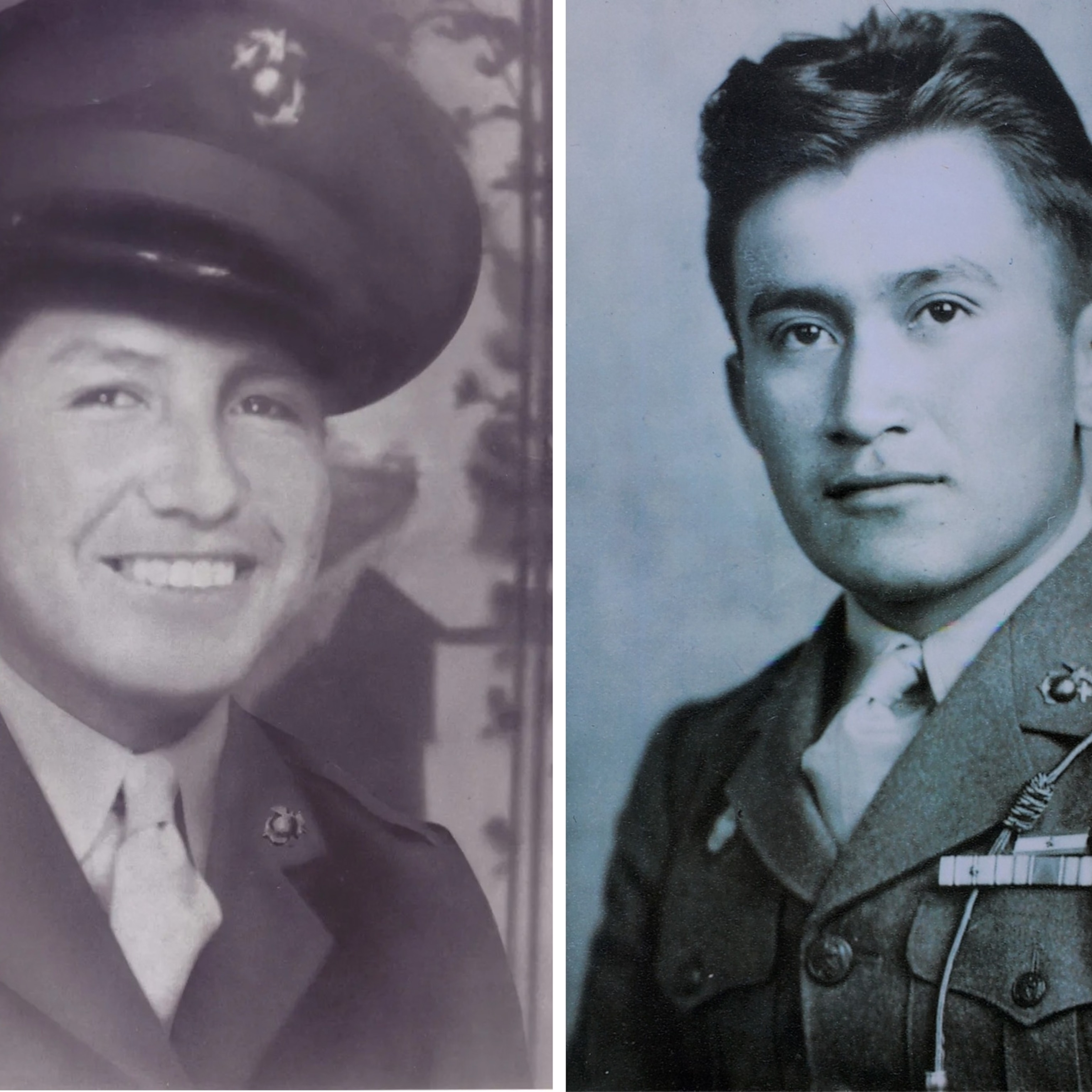

AIM was founded in 1968 by Bellecourt, his older brother, Vernon Bellecourt, Dennis Banks, and Russell Means. The organization was created to fight Native American racism and advance social justice issues. AIM deployed bold tactics to bring attention to the historical mistreatment and misrepresentation of American Indians, including the casual use of slurs and stereotypes built into American culture and social institutions such as schools. The group famously radicalized the Native American protest movement, notably with an armed occupation of Wounded Knee, South Dakota, in 1973, and a seven-day sit-in at the Bureau of Indian Affairs a year earlier. The group also vigorously challenged the way American Indians were portrayed in film and in the nation’s sporting landscape.

Cleveland’s major league baseball team had long been on AIM’s radar—especially the Bellecourt brothers. The two were often among the scores of local and national Native American activists who for years descended on Cleveland, Ohio, each Opening Day to stage demonstrations at the downtown stadium where the team played. Vernon Bellecourt was arrested in Cleveland during the 1997 World Series and again in 1998 during protests focused on the Cleveland mascot, Chief Wahoo, which the team dropped in 2018.

The long-running protests against the team’s name appeared to bear fruit last summer when Cleveland Indians owner, Paul Dolan, asked his leadership team to earnestly explore the idea of changing the name.

“It was the right thing to do,” Dolan said at a press conference in July announcing the name change. He also acknowledged that the change would not go well with some. “I’m 63 years old. They’ve been the Indians since I was aware of them, probably four or five years old. We’re not asking anybody to give up their memories or the history of the franchise,” Dolan said.

For Bellecourt, Dolan’s explanation for the name change was a missed opportunity. The aging activist said the apparent social awakening that the nation is currently experiencing continues to lack an honest conversation about the historical mistreatment of Native Americans and the damaging misappropriation of their imagery.

“It would have been enlightened if the Cleveland team had fully explained why they changed the name. If the team had explained how the history of the Indigenous people has largely been erased, ignored, misused, or distorted. It could have been an educational moment for the nation, which continues to misappropriate the culture and dignity of Indigenous people,” said Bellecourt.

David Glass, an enrolled member of the White Earth Nation and president of the National Coalition on Racism in Sports and Media (NCRSM), which is comprised of academics and Native American activists, including Bellecourt, was more charitable. Glass told me that he was happy that the Cleveland baseball team had decided to change its name. While there has been movement in recent years for some teams and schools to examine and, in some cases, to change offensive names, Glass said such change generally doesn’t come easy.

“We routinely get requests from communities to explain why the imagery and names are bad or harmful,” said Glass. “We welcome those opportunities. We try to work behind the scenes. It’s not about tearing communities apart. When we explain how racism and bigotry is often based in ignorance, people are more open for a conversation.”

Deb Haaland, who in March 2021 became the first Native American to serve as a cabinet secretary when the United States Senate confirmed her appointment as Secretary of the Interior, has long railed against the stereotyping of Indigenous people in sporting imagery and organizational names. She has occasionally taken to Twitter to voice her concerns on this issue.

“The sooner we recognize the damage that Native American mascots do to perpetuate harmful stereotypes, the sooner we can address longstanding misunderstanding and racism toward Native communities,” Haaland tweeted in May 2019, while then serving as a U.S. Representative from New Mexico.

Perhaps no sporting team in the nation’s history better exemplifies the resistance to change than the team formerly known as the Washington Redskins. In 1937, the team was formed after the Boston Redskins decided to relocate to the nation’s capital.

Some 35 years later, the Washington football team changed its fight song to remove the words “scalp ‘um” after Native American leaders protested the song’s lyrics and the team’s name.

In 1992 a petition to revoke Redskins trademarks for disparaging Native Americans was filed with the United States Patent and Trademark Office. The petition lingered for 17 years before ultimately being denied.

In 2013 Daniel Snyder, the team’s owner, said in an interview with USA Today: “We’ll never change the name. It’s that simple. NEVER—you can use caps,” he told the newspaper.

Fast-forward to May 2020 when George Floyd was killed while in police custody in Minneapolis. The protests following the murder almost instantly changed the way America looked at itself and how corporate leaders viewed their brands. Less than six weeks after Floyd’s murder, investors reportedly worth over $620 billion sent letters to Nike, Pepsi, and FedEx demanding that they end their sponsorship of the Redskins. That same week FedEx, which holds naming rights to the team’s stadium, asked the Redskins to change the name.

Ten days later Snyder’s team announced that it was immediately changing its name and logo. The Redskins would henceforth go by the moniker Washington Football Team until a permanent name was created.

“When Washington changed its name, it wasn’t because Dan Snyder heard our voice,” said Glass with the NCRSM. “It was the sponsors who finally got it and put pressure on that ownership to make a change.”

“The world has taken a dramatic turn in recent days. Many young people are starting to question what they’ve been taught and the historical images that they have inherited. That represents social progress. Just as important, sponsors are now more concerned with how their money is spent and with whom,” Glass added.

Much work lies ahead in the effort for social justice. A little over a year after the Washington football team changed its name, the National Congress of American Indians (NCAI) issued a statement in July raising awareness about the continuing use of Native “themed” mascots or names at schools across America. In August, NCAI announced that it launched a state tracker to monitor and share updates on the movement to end Native themed school mascots. At least one school district has taken action. Last month, Ohio’s Cuyahoga Heights School Board voted unanimously to remove “Redskins” as a mascot and logo.

“Once this country makes a concerted effort to start teaching the true history of who we are,” said Glass, “is when this country will further evolve into true greatness.”