The world’s oldest rock art discovered in Indonesia

The 67,800-year-old hand stencil looks like a claw—and provides new clues about early human cognition and the migration to Australia.

On Muna, a tropical island off southeastern Sulawesi, Indonesia, lies a cave decorated with prehistoric paintings. Locals call it Liang Metanduno. They visit the archaic art gallery to marvel at depictions of flying human figures, boats filled with passengers, and mounted warriors drawn with red, brown, and sometimes black pigment.

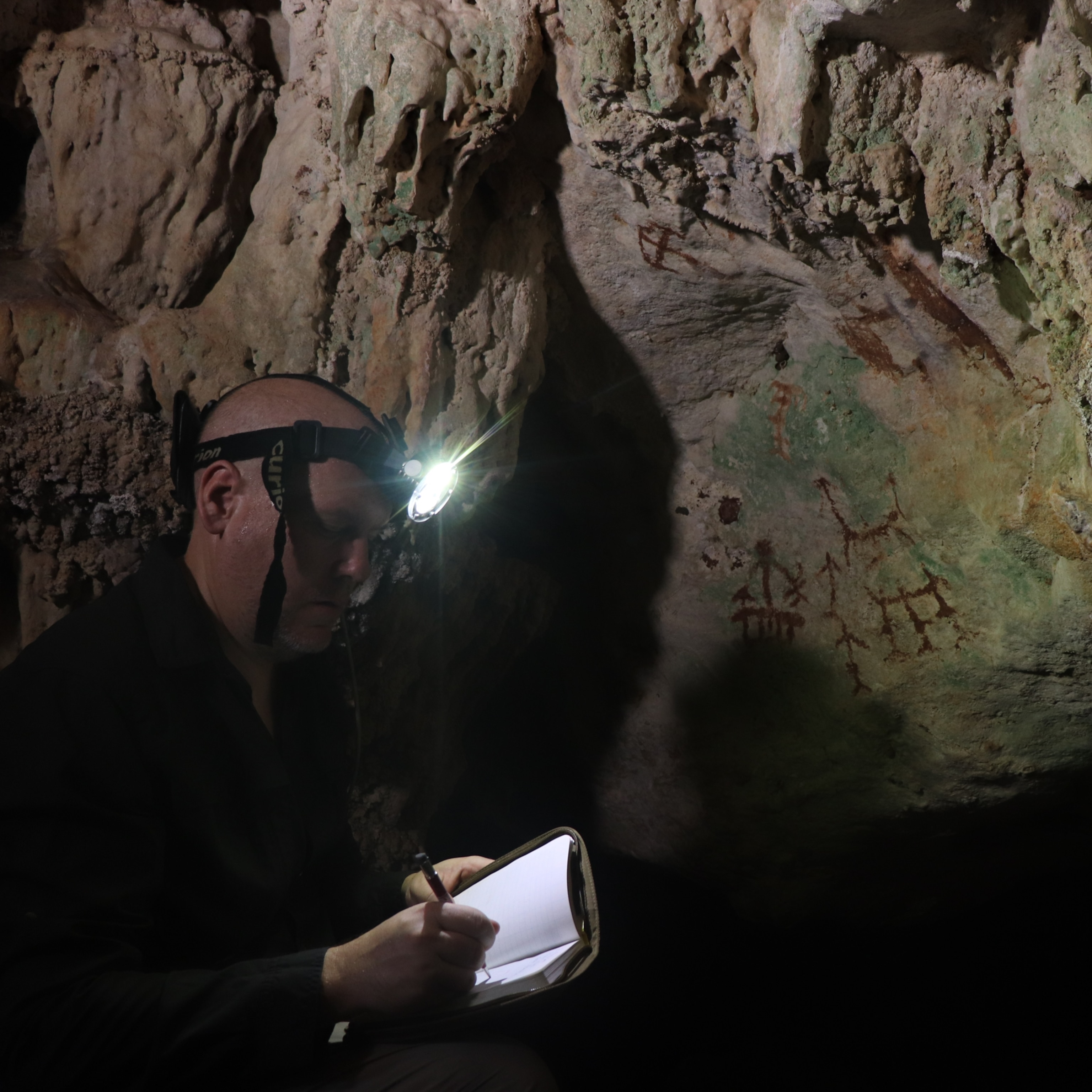

In 2015, Adhi Agus Oktaviana, an archaeologist at Indonesia’s National Agency for Research and Innovation (BRIN), travelled to Liang Metanduno in search of a much older form of human artistic expression, one that predated the birds, pigs, and horses painted on its walls only a few thousand years ago.

On the ceiling near a brown scribble of a chicken, Oktaviana found it: two hand stencils, one of which had a pointy finger like an animal claw.

Using a new dating technique, he and National Geographic Explorer Maxime Aubert, an archaeologist and geochemist at Griffith University in Australia, along with other colleagues, tried to determine the artwork's age. They discovered that the claw-like hand stencil is at least 67,800 years old—the oldest rock art attributed to modern humans found so far. They reported their findings Wednesday in Nature.

“The age of the hand stencil in Muna shows that early modern humans who inhabited Nusantara during the Late Pleistocene epoch already had sophisticated cognition,” says Oktaviana, referring to the area that is now the Indonesian archipelago.

The newly dated Muna art is about 16,600 years older than the rock art the researchers previously documented in the Maros-Pangkep caves in Sulawesi, and about 1,100 years older than hand stencils found in Spain believed to have been drawn by Neanderthals.

(Ancient cave art may depict the world's oldest hunting scene)

“This is the strongest piece of evidence that our species was present in [the] Indonesian archipelago at that time and they playfully and imaginatively transformed a human hand mark into something else,” Adam Brumm, an archaeologist also at Griffith University and a coauthor of the paper, said during a press conference.

The researchers also dated hand stencils found in two other caves on the surrounding islands. Their analysis shows the stencils were created between 44,500 and 20,400 years ago. That suggests the ancient inhabitants of Indonesia continued making rock art for tens of thousands of years until the peak of the last ice age, when sea levels were lower, and a chunk of Southeast Asia was part of an exposed landmass called Sundaland. The authors add that the findings may provide clues to better understand the population that crossed land bridges and hopped across islands to become the first inhabitants of Australia some 65,000 years ago.

Intelligence and imagination

To figure out how old the hand stencils are, the researchers used a technique developed by Aubert and others called laser-ablation uranium-series dating, which allows for the accurate dating of ocher-based rock art. This method uses a laser to collect and analyze a very tiny amount of calcium carbonate deposits that formed on the top of a pigmented layer.

At Southern Cross University in Australia, they used the technique and dated the claw-like hand stencil to between 75,400 and 67,800 years old, and the other hand stencil to around 60,900 years ago.

The Muna finding adds to recent discoveries of rock art in Indonesia that offer insight into early human intelligence. In 2019, Aubert and Oktaviana reported finding rock art depicting theriantropes—human figures with animal heads and tails—hunting warthogs and Sulawesi’s endemic dwarf buffalo, anoa. The narrative scenes, later found to be 51,200 years old, show that early humans living in Indonesia were capable of imagining non-existent beings. The newly dated hand stencils in Muna show signs that the artists who painted them also had this same cognitive ability, the researchers say.

As the team observed, one of the stencil fingers looks pointy like an animal claw, an art style that has only been found in Sulawesi, they say. Aubert says he can only speculate that it has something to do with human-animal relationships. But the fact that the artist modified the hand stencil—either by retouching the finger with a paint brush or by moving their hand so it creates a claw-like effect—shows “a complicated thought,” Aubert says.

“They are drawing something that doesn’t really exist,” he says.

R. Cecep Eka Permana, an ethnoarchaeologist at the University of Indonesia who was not involved in the research, says the hand stencils might have related to the practice of warding off misfortune, a ritual that can be found in some indigenous groups in Sulawesi.

Such evidence for a sophisticated mind, the researchers say, challenges Eurocentric views of ancient intelligence that once dominated archaeology.

“A lot of people believed that we became cognitively modern when they arrived in Western Europe,” says Aubert. This view, he says, stems from a lack of advanced dating technology for rock art at the time.

(40,000-year-old cave art may be world's oldest animal drawing)

Most rock art dated in Europe was made with charcoal, allowing scientists to conduct carbon dating, says Aubert. In the meantime, Southeast Asian rock art is mostly made with ochre, an inorganic red-brown pigment derived from iron oxide, which is difficult to carbon date. The new dating technique helps to show that intelligent humans lived in the region, far before modern humans set foot in Europe, the authors say.

It is also evidence, they say, that early people in this region may have also had the intelligence necessary to perform a seafaring journey to Australia.

Clues to ancient Australian migration

Research suggests that some modern humans left Africa 60,000-90,000 years ago, walking through the Middle East and South Asia before finally reaching Sundaland, which now comprises Sumatra, Java, and Borneo.

There, they had to sail across the sea, hopping from one island to another, to finally reach Sahul, the landmass that covered Papua and Australia at the time. Sulawesi and other tropical islands in between the two regions—known as the Wallacea region for its unique geological history and flora and fauna—hold important clues to the story of this epic human migration.

Because Pleistocene-era human remains in Sulawesi are rare, rock art is among the few sources of evidence for human presence at the time.

“It’s an intimate window to look into the past,” says Aubert.

Oktaviyana says Aboriginal rock art in Madjebebe, northern Australia, was most likely inherited from their ancestors in Nusantara, the same people who put their hand stencil in Muna 67,800 years ago. Excavations of human remains might take a long time, “but archaeological science could fill this gap of knowledge,” he says.

Helen Farr, a maritime archaeologist at the University of Southampton in England, not involved in the work, says the finding in Muna is interesting.

“It’s great to see the art preserved and dated, providing a small window to a wide range of activities that’s often missing in the [archaeology] of this time depth,” she says.

(Rock art in Venezuela may be the sign of a lost ancient culture)

She adds that the new finding supports her genetic research on the peopling of Sahul, which showed that “people had seafaring technology and were capable of open water crossings between Wallacea and Australia by 65,000 years ago.”

But which route did these people take to reach Australia?

The finding in Muna suggests they could have taken the northern route, hopping from the Indonesian islands of Sulawesi, Maluku, and Papua. But Oktaviana says it’s possible they could have taken the southern route, too.

During an interview with National Geographic, he opened Google Maps and zoomed in on a very small, isolated island farther south, between Sulawesi and Flores, which may have been a possible early stepping stone to Australia.

“Look at this,” he says. “There’s a cave here, and there might be another rock art.” He says he will need to seek funding to visit the island and find out. But for Oktaviana, it’s worth trying if there’s a chance he can make another discovery about ancient human artwork and migration there, as he did in Muna.