These lovely little statues enchanted ancient Greece

The elegant Tanagra figurines, so popular more than a thousand years ago, provide an intimate look into the lives of the everyday people who loved them.

In the 1860s peasants from the town of Bratsi, in the Greek region of Boeotia, north of Athens were plowing the soil when they unearthed an ancient grave, and then another and another. Although there were no lavish grave goods to be found, the burial sites did harbor a magnificent treasure of a different kind. As they dug, the peasants began to unearth beautifully made terracotta figurines. The fascinating little statues, mainly of female figures between three and nine inches tall, were everywhere. Eventually hundreds would be collected.

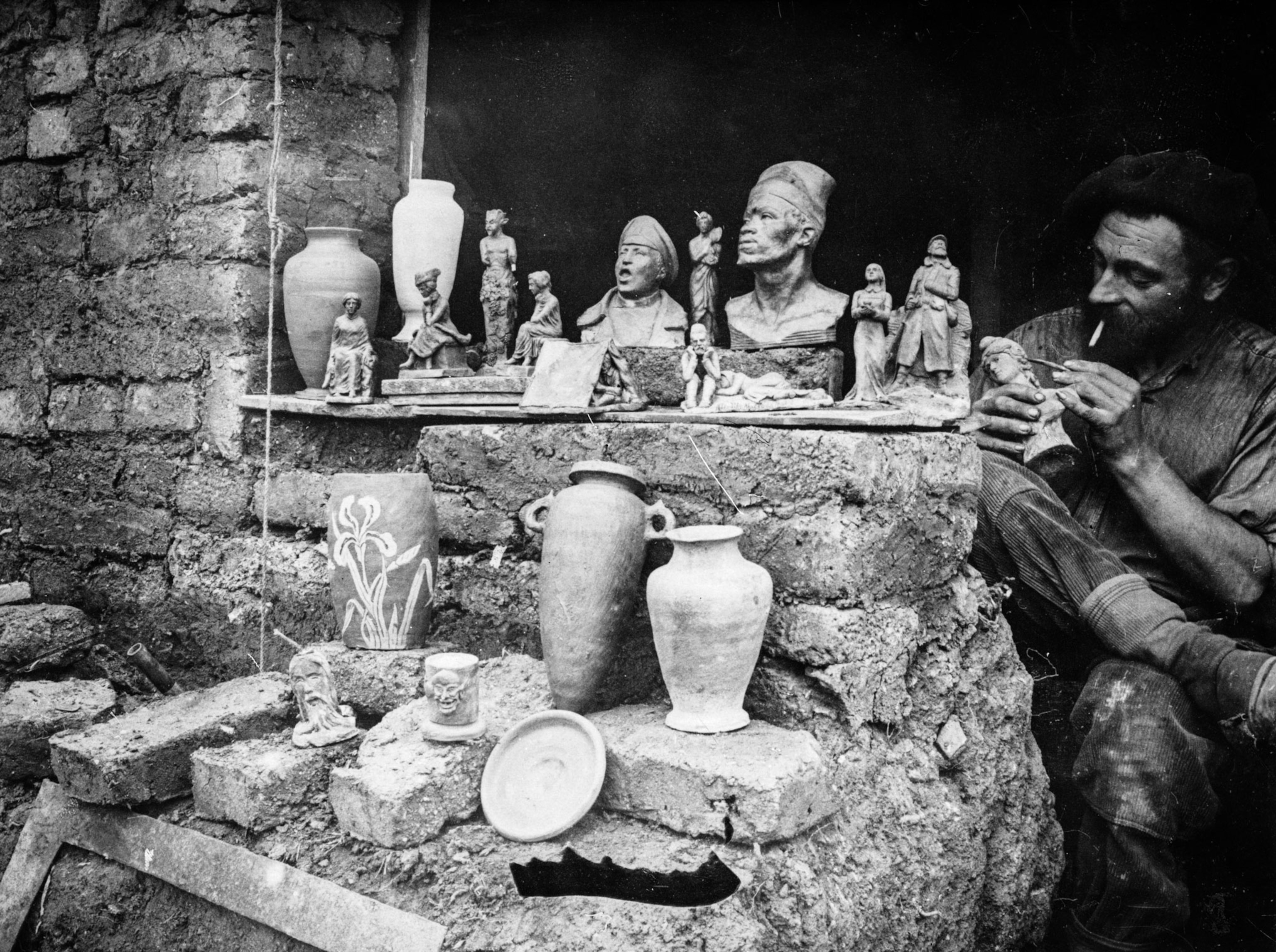

The accidental archaeologists offered the pieces for sale to anyone they met and news of the extraordinary find soon spread, attracting treasure hunters. Grimadha, near the location of the ancient city-state of Tanagra, was a popular target for looters. It is estimated that more than 8,000 graves were dug up as people hungrily searched for the figurines.

(This colossal Greek statue inspired art long after it was destroyed.)

The illegal excavation of the Tanagra necropolises became an open secret, and Greek authorities eventually decided to intervene, sending archaeologist Panayiotis Stamatakis to oversee the first official dig in 1874. The archaeologists’ attempt at imposing some order on the excavation was too little, too late. Their findings lacked the necessary detail to be of much academic use. In 1911 excavations began to be carried out more methodically, but it was not until the 1970s, more than a century after the first figurines came to light, that excavations were conducted with the proper rigor and care.

Popular girls

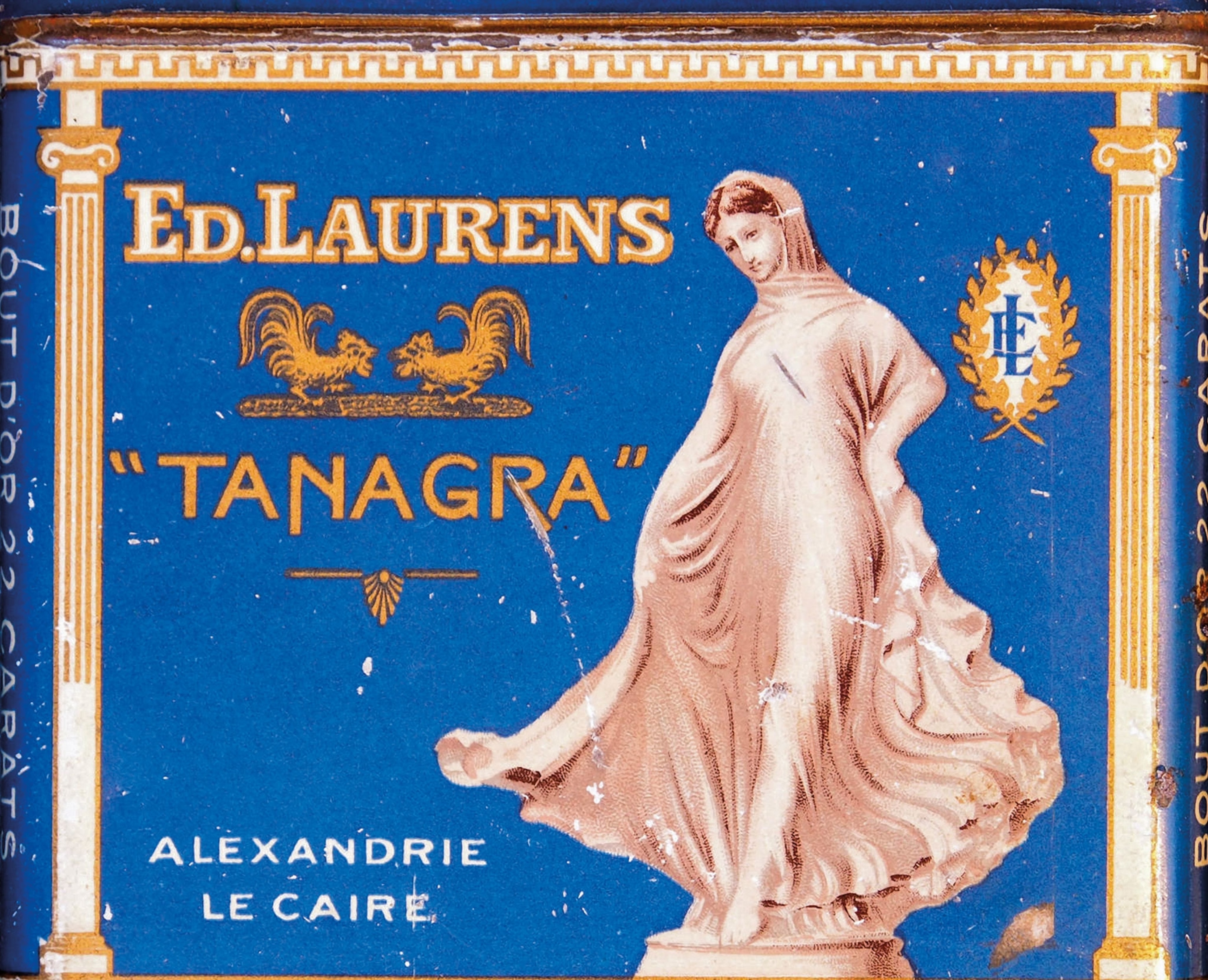

The demand for Tanagra figurines seemed to have no bounds in late 19th-century Europe. The statuettes, mainly of women, fit in with the ideals of feminine beauty and fashion of the Belle Epoque. The softness, grace, and modesty idealized in the diminutive figures, their robes, drapery, head coverings, and hairstyles contrasted with the austere depiction of male figures: classical Greek gods, statesmen and soldiers.

The presence of the government archaeologists at Tanagra did not stop the grave robbing. Insatiable demand for the figurines drove more clandestine removal from the necropolises. Fake figurines also began to enter the antiquities market. Some of the imitations were clumsy copies, but others were skilled forgeries and more difficult to detect. Local villagers would sell the figures–authentic and otherwise–to whomever would buy them, at increasingly exorbitant prices.

Many of these imposters fooled experts for years. They even made their way into prominent museum collections. Recent thermoluminescene analysis of Tangara figurines in the German State collections has revealed that as many as 20 percent of them are fakes.

(The history and excavation of UNESCO World Heritage Site Delphi.)

Custom models

The delicacy of the Tanagra figurines reveals how skilled the Greeks were in the art of coroplasty, or clay modeling. The body would be shaped from a two-part mold, and then the head and arms (also created from molds) would be attached. The figure would be customized through different poses and by adding different decorative elements, like crowns and flower hats.

Before firing, artisans applied a mixture called white slip, made of water and clay. After the clay had baked, water-based pigments were applied to a layer of fresh lime plaster. The figures were painted in naturalistic hues and soft colors. Rich shades of blue and gold leaf were used sparingly, as both were very expensive at the time. The figures were popular around the Mediterranean in the fourth century B.C. Figurines have been found in Corinth, Macedonia, Asia Minor, southern Italy, north Africa, and as far away as Kuwait.

Form and function

The figurines discovered at Tanagra demonstrate how the wide artistic range of this kind of Greek sculpture. The excavations unearthed hundreds of different female forms, ranging from demure matrons to nubile veiled dancers and girls at play. Rather than exalting the gods or statesmen, these quiet statues were an intimate look into the lives of everyday women and their children, an experience which is often not reflected in the literature of the time. Their clothing and their gestures reveal contemporary attitudes towards female roles in society.

Scholars hold differing opinions on the function of these small statues. It’s possible that they manufactured for different uses. Since the majority of figurines were grave goods, it is possible they played an official role in burial practices. It’s also possible that the original rationale behind burying the figurines was eventually forgotten, while the custom of depositing them remained. Many Tanagra figurines were found in domestic settings, which suggests that they could have been affordable, decorative art.

Some of the most famous figurines, such as the Lady in Blue and the Sophoclean, seem to have been inspired by large statues by master sculptors such as Praxiteles and Leochares. Some experts believe that the Tanagra figurines were produced purely for their aesthetic appeal, as mini replicas, a practice that would later be developed by Roman patricians when they decorated their residences.