These ancient Greek weapons were quite literally toxic

Whether laced with viper venom, poison gas, or deadly pathogens—these weapons of war relied on nature's armory to slay the enemy.

How ancient is biological and chemical warfare? When was the Pandora's box of weaponized nature first opened? The answer is surprising: Humanity’s genius for turning natural forces into weapons has deeper roots than one might imagine. Many historians assume that biological and chemical weapons are modern inventions. They believe that the ability to turn venoms, germs, toxins, and other dangerous natural agents into weapons requires a scientific understanding of toxicology, biology, epidemiology, and chemistry. To harness nature’s powers, one would surely need advanced technologies and sophisticated delivery systems.

(How do we know what ancient Greek warriors wore? It's in The Iliad.)

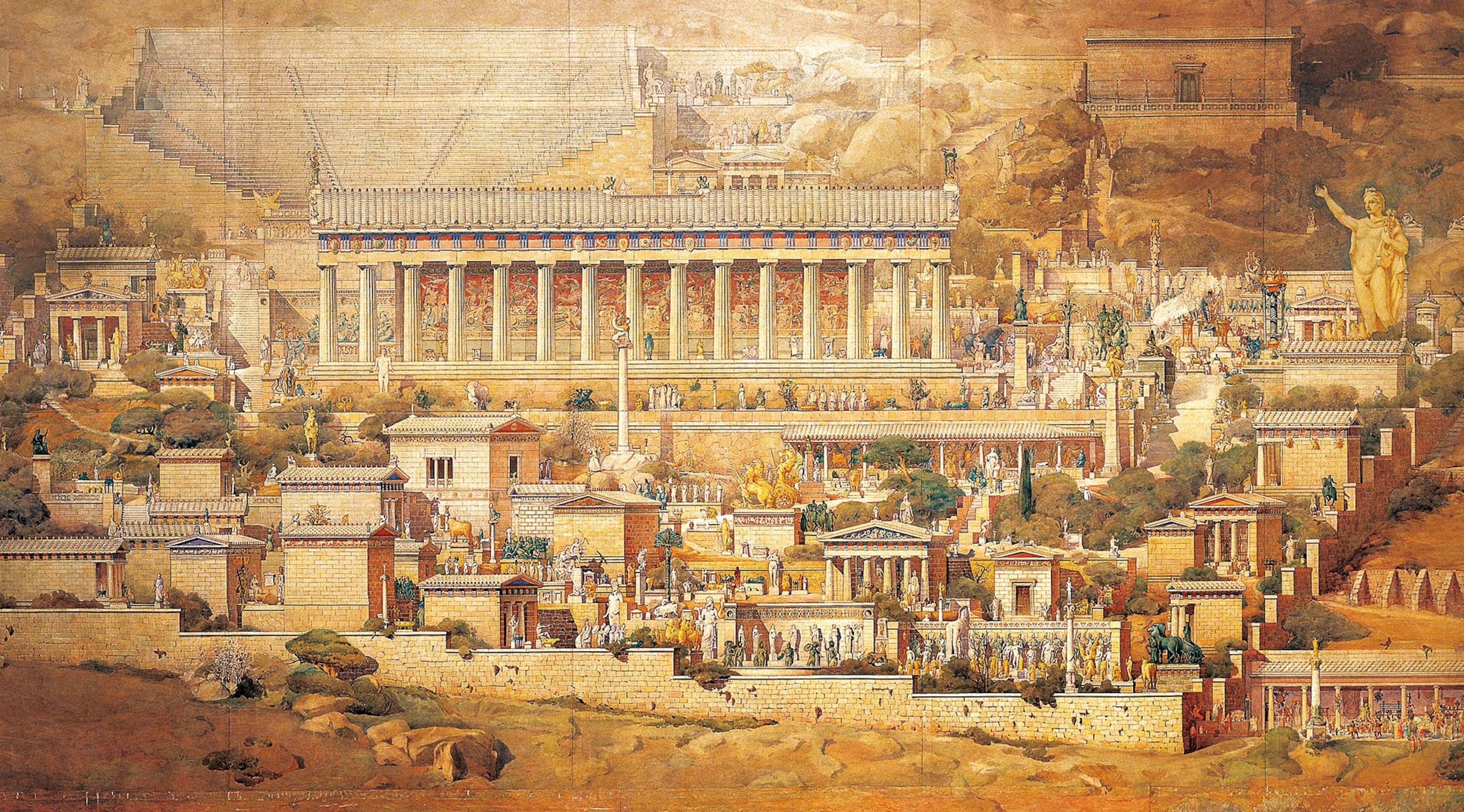

Greek myths are littered with biological warfare, from weapons tinged with poisonous Gorgons’ blood to the deadly arrows of Apollo and Artemis. Borrowing the destructive forces of nature was more than fantasy. Incidents of biological warfare have been documented in numerous ancient texts. More than 50 authors provide evidence that biological and chemical weapons saw action in historical battles around the Mediterranean, India, and China.

Many historians also assume that warfare in antiquity was grounded in honor, courage, and skill. They take for granted that poison weapons and unscrupulous, unfair tactics were forbidden by ancient “rules of war”—and that, with a few exceptions, those rules were followed in classical antiquity. Turning nature into military weapons was imagined and practiced much earlier and more extensively than was commonly assumed. There were no formal, agreed-upon “rules of war” that hindered their use. Attitudes about gaining unfair advantage with poisons and unconventional weapons were complex and ambivalent in antiquity. Underhanded, secret strategies to avoid close combat were not taboo, but they did entail practical and ethical problems.

Poisoning the well

The sheer variety of options was staggering. Besides shooting arrows steeped in snake venom, germs, toxic plants, and fiery materials, ancient armies also contaminated their enemies’ water.

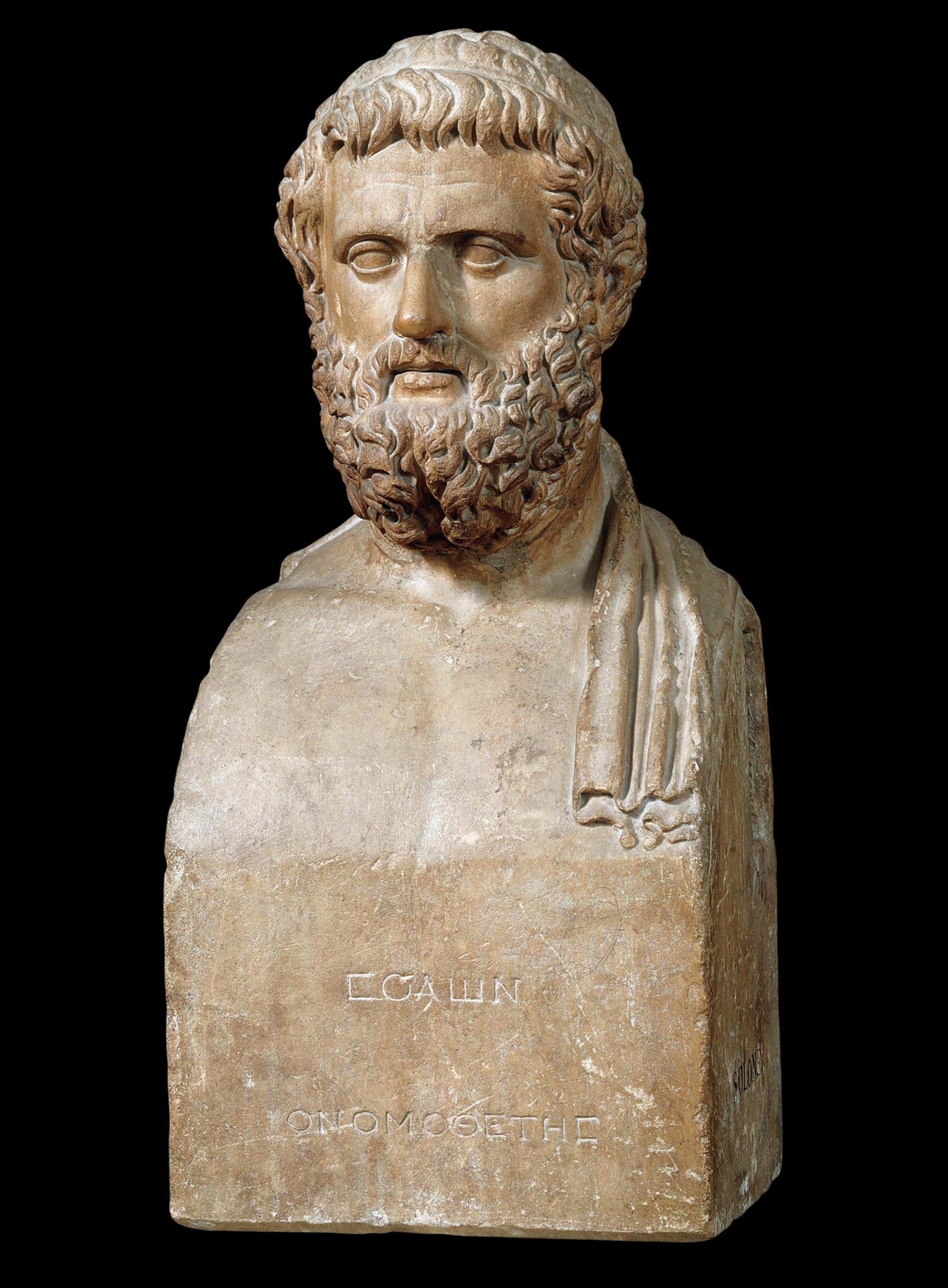

The earliest documented case of poisoning water occurred during the First Sacred War in Greece, about 590 B.C. The Athenians and their allies contaminated the water supply of the besieged city of Kirrha, using hellebore, a toxic plant that grows in abundance all around the Mediterranean. Notably, historical sources attribute the plot to four different men, one of them a doctor.

This demonstrates the collateral damage biological warfare inflicts. It harms not only soldiers but also noncombatants: The elderly, women, and children inside the walls of Kirrha were all killed. After the First Sacred War, the Athenians and their allies agreed never to poison the water of fellow members of their alliance.

(Is Troy True? The Evidence Behind Movie Myth)

Not all historical examples of “biochemical” tactics in antiquity fit modern scientific definitions, but they do represent the earliest evidence of the intentions, principles, and actual practices that would evolve into present-day biochemical weapons. Chemical weapons are defined as poison gases, choking and blinding clouds of smoke, and combustible incendiaries unquenched by normal means. Biological weapons are harvested from living organisms (such as animal venom and poisonous plants) or are full-fledged pathogens themselves that infect the human body. The use of animals was the precursor of entomological and zoological weapons research actively pursued today.

(How the Oracle at Delphi, a city fought over in the First Sacred War, was found.)

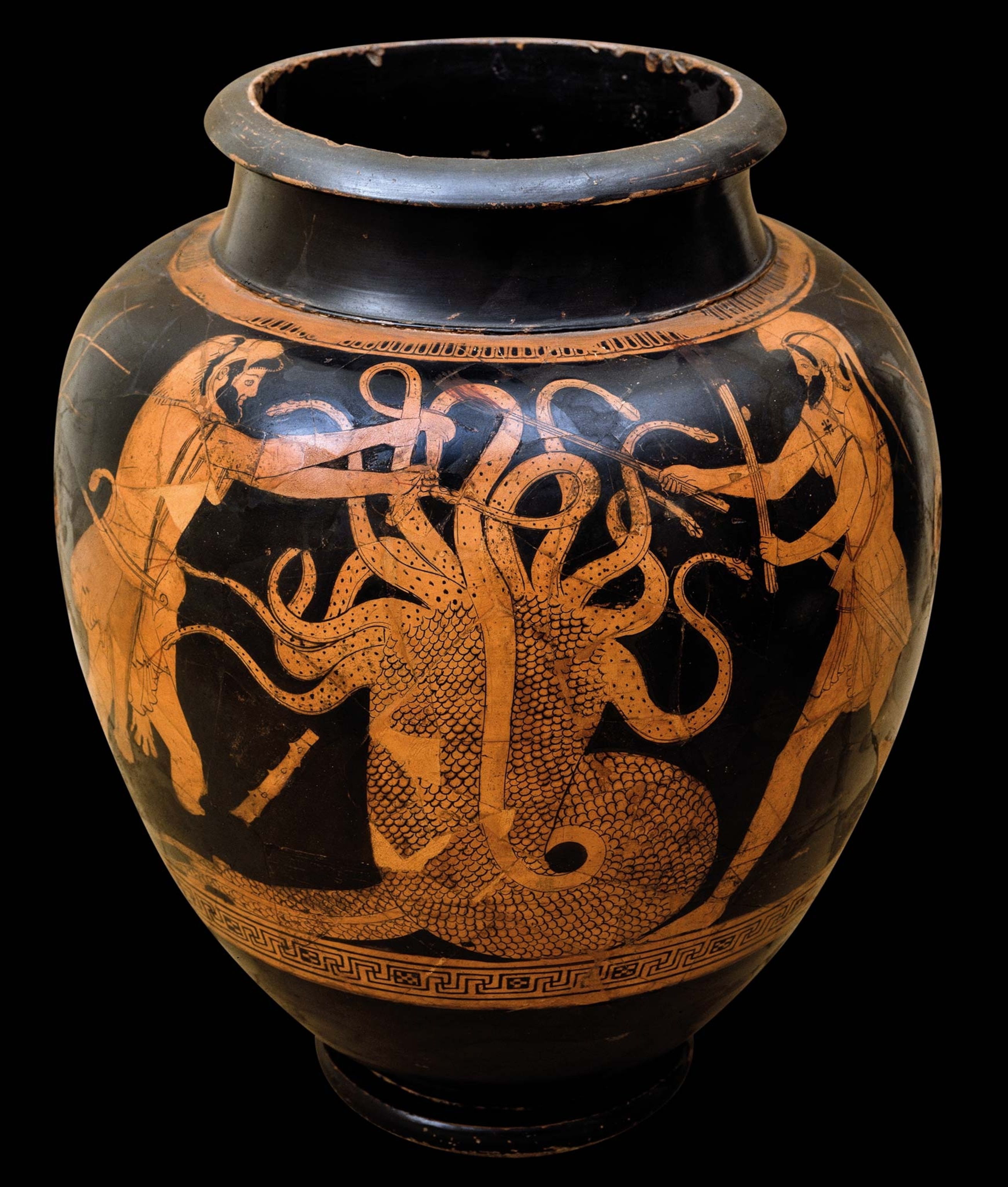

Hercules and the Hydra

The ancient Greeks understood that, by their very nature, biological and chemical weapons tend to be very difficult to control. Remarkably, ancient myths about the creation of biological weapons recognized the dilemmas that still surround such armaments today. In the myth of Hercules, the hero slays the many-headed Hydra and dips his arrows in the monster’s venomous blood, creating a biological weapon. A chain of unintended consequences is set in motion, and these arrows bring about a very painful death for Hercules himself.

Like the Hydra’s multiplying heads, real-life problems proliferate whenever one resorts to biological tactics. The weapons almost seem to take on a life of their own. The potential for blowback, collateral damage, and self-injury always looms. Poison and arrows were deeply intertwined in the ancient Greek language itself. The word for poison in ancient Greek, toxicon, derived from toxon, arrow. Poison arrows were by far the most popular bioweapons in antiquity. Avast variety of substances, from harmful plants and viper venom to stingray spines and toxic insect guts, have been used around the world to poison projectiles.

Blood of the hydra

Shoot that poison arrow

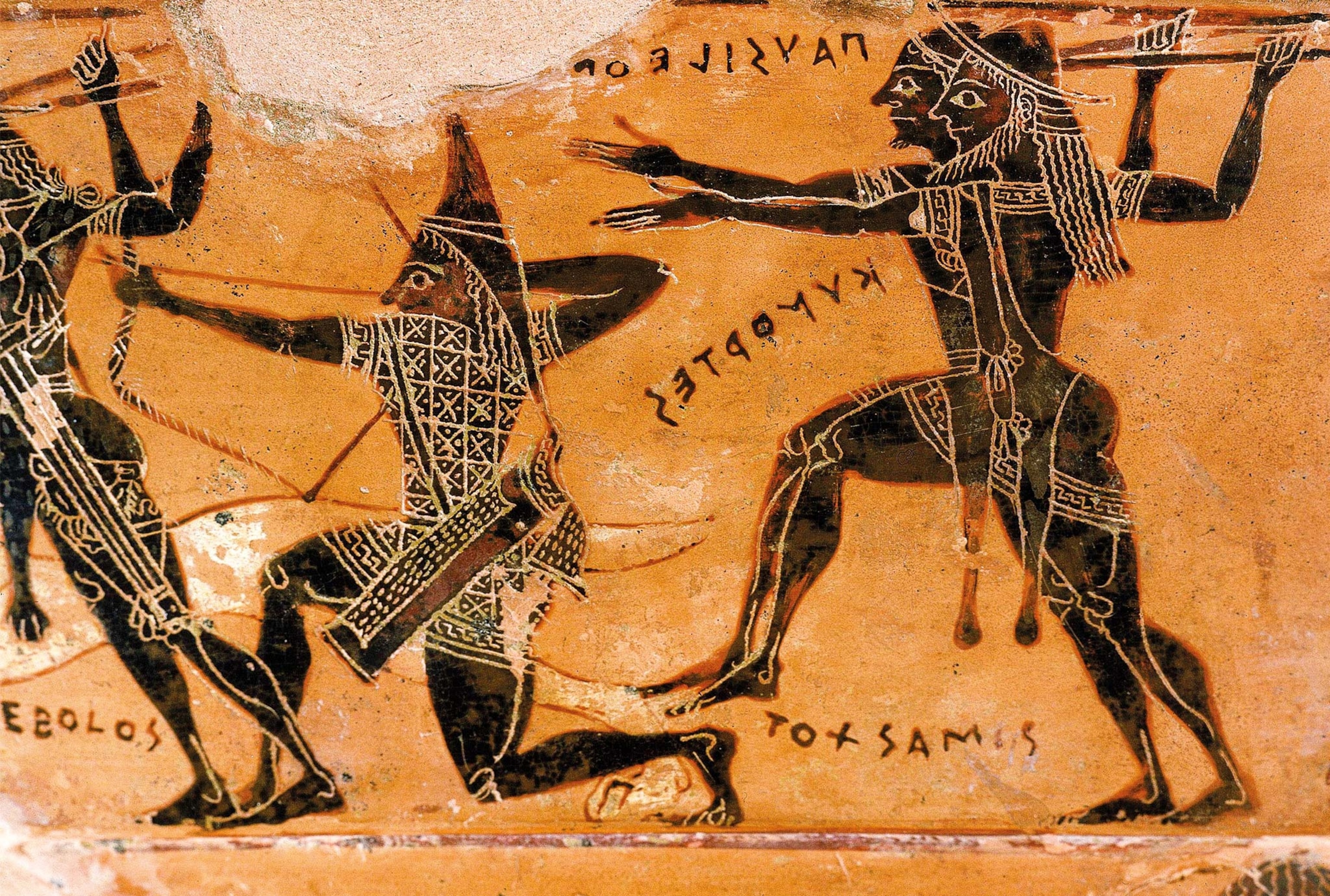

Some of the most dreaded biological warriors of antiquity were the Scythians, nomad archers of the Eurasian steppes whose members were the inspiration for the Amazons in Greek myths. Archaeological excavations of Scythian warriors buried with their quivers reveal that they used wickedly barbed arrows affixed to wooden shafts. The shafts were decorated with patterns to resemble venomous vipers.

Facing a hail of arrows painted to look like flying snakes with deadly fangs would have been daunting enough, but the experience was even more harrowing, for the Scythians dipped their arrowheads in a notorious poison called scythicon. Ancient Greek sources described it as a nasty concoction of snake venom, decomposed vipers’ bodies, human blood, and dung.

The ingredients were combined and then allowed to putrefy over several months. A slight scratch from one of these arrows brought a ghastly death or a slow torture from a wound infected with gangrene and tetanus. The fact that the Greeks knew the ingredients suggests that the Scythians advertised it widely, to spread fear. Indeed, a powerful feature of biological and chemical weapons of any time period is psychological.

Alexander the Great's natural arsenal

In 326 B.C., Diodorus of Sicily, Strabo, and Quintus Curtius reported that Alexander the Great and his Macedonian army encountered poison projectiles in Pakistan and India. The warriors defending the city of Harmatelia had tipped their weapons with a poison derived from dead snakes left to rot in the sun. As the animals’ flesh decomposed, their venom supposedly suffused the liquefying tissue.

Diodorus’s description of the agony of the wounded is vivid. Alexander’s soldiers first went numb, then suffered stabbing pains and wracking convulsions. Their skin became cold, and they vomited bile. Gangrene spread rapidly, and the men died a horrible death. Diodorus’s details allowed historians to determine that the venom came from the Russell’s viper. Its venom causes numbness and vomiting, then severe pain and gangrene before death, just as described in Diodorus’s accounts.

(Who was Alexander the Great?)

It is interesting that both the Scythians and the Harmatelians used the entire bodies of vipers to make arrow poisons. A modern herpetological discovery suggests a good reason: a snake’s stomach contains harmful bacteria. Moreover, scientists recently learned that vipers retain surprisingly large amounts of feces in their bodies. A dead viper’s excrement would add even more foul bacteria to the mixture.

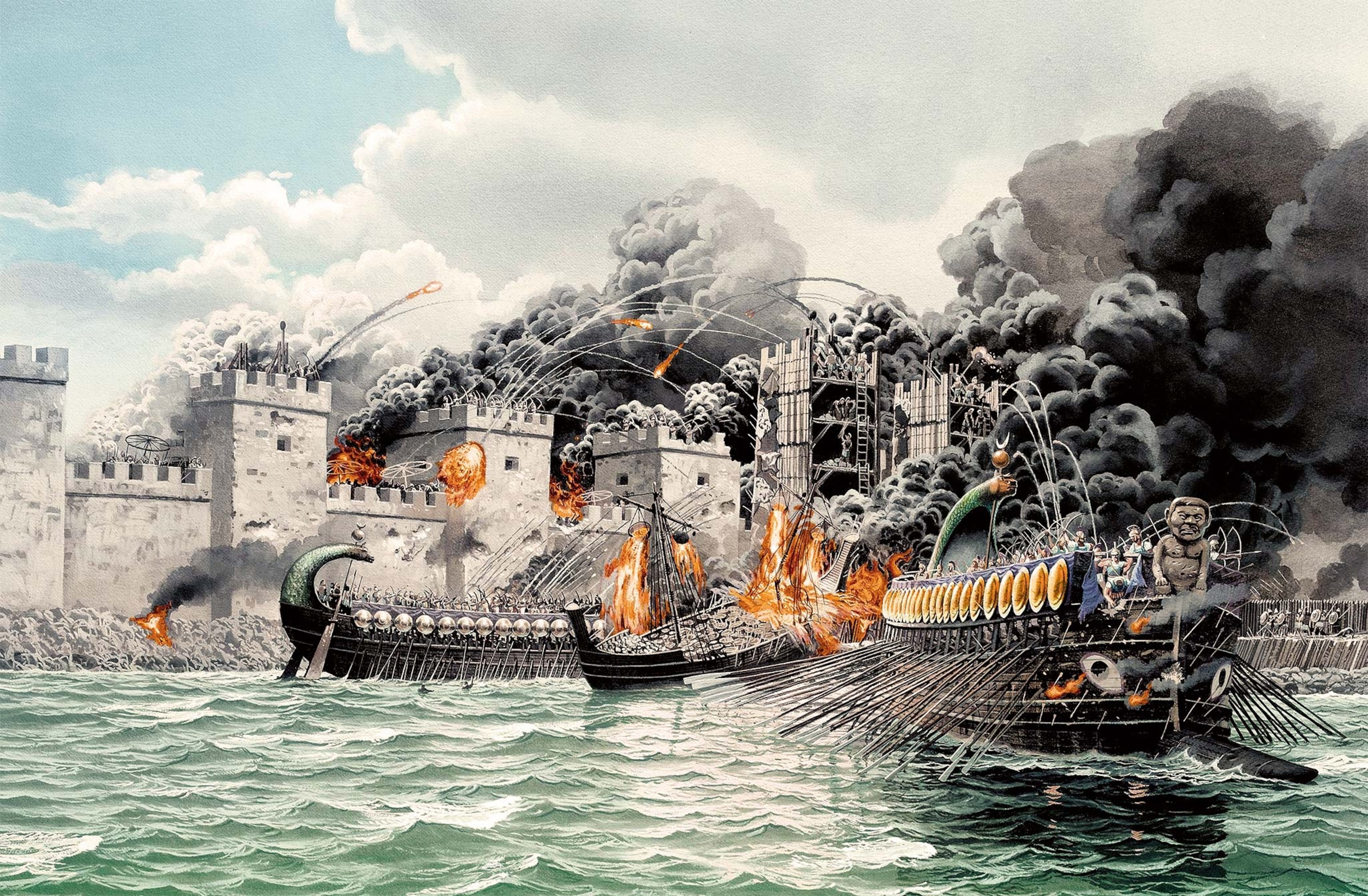

In 333 B.C., Alexander the Great’s army faced another devastating unconventional weapon. The Phoenicians defending Tyre (in Lebanon) ingeniously heated sand in shallow bronze bowls. Then they rained the red-hot sand down onto Alexander’s men. Ancient historians describe the ghastly scene as the hot grains sifted under the soldiers’ armor and burned deeply into their flesh, causing agonizing death. The burning shrapnel anticipated the fatal, deep burns inflicted by modern thermite or white phosphorus bombs, invented more than 2,000 years later and recently used in the same geographic region.

Toxic gas

Fire also led to one of the earliest historical instances of using poison gas against an enemy. In 429 B.C., during the Peloponnesian War, Spartan forces attacked the fortified city of Plataea. The historian Thucydides tells how the Spartans heaped a massive pile of firewood next to the city wall, then poured pine tree resin (pitch, the source of turpentine) on the logs.

In a bold innovation, the Spartans then added lumps of sulfur, found in acrid-smelling mineral deposits in volcanic areas and hot springs. The combination of pitch and sulfur accelerants “produced a conflagration that had never been seen before, greater than any fire produced by human agency,” declared Thucydides.

Indeed, the blue sulfur flames and foul stench must have been sensational. The fumes were deadly; burning sulfur creates toxic sulfur dioxide gas, lethal if inhaled in large quantities. The Plataeans abandoned their burning palisades, but then the wind reversed and a severe thunderstorm put out the fire. Plataea was saved.

Fire, smoke, and poison

Five years later, in 424 B.C., Sparta’s allies, the Boeotians, invented a “flamethrower” device to sidestep shifting winds. Thucydides described how the contraption destroyed the wooden fortifications at Delium, held by the Athenians. The Boeotians hollowed out a huge wooden log and plated it with iron. They suspended a large cauldron by a chain attached to one end of the hollow beam and inserted an iron tube, curving down into the cauldron.

The cauldron was filled with burning coals, pine resin, and sulfur—the same accelerants innovated by the Spartans at Plataea. Mounted on a cart, the apparatus was wheeled next to the walls. The Boeotians attached a very large blacksmith’s bellows to their end of the beam and pumped great blasts of air through the tube to direct the chemical fire and toxic gases at the walls. The walls were incinerated, as were defenders as they fled their posts, and Delium was captured.

(This ancient Greek warship ruled the Mediterranean.)

As noxious smoke was hard to control and direct, it was often easier to employ in confined spaces like tunnels. In western Greece in A.D. 189, during the long siege of Ambracia, the defenders invented a smoke machine to repel the Roman sappers tunneling under the city walls. Polyaenus says the Ambracians “prepared a large jar equal in size to the tunnel, bored holes into the bottom, and inserted an iron tube.” They packed the pot with layers of fine chicken feathers and smoldering charcoal and capped the jar with a perforated lid.

Then they aimed the perforated end of the jar of burning feathers at the tunnelers and fitted blacksmith’s bellows to the iron tube at the other end. With this device—which calls to mind the primitive flamethrower at Delium—the Ambracians filled the passage with clouds of acrid smoke, sending the choking Romans rushing to the surface. “They abandoned their subterranean siege,” was Polyaenus’s terse comment.

But why did the Ambracians burn chicken feathers? It turns out that feathers are composed of keratins containing cysteine, a sulfuric amino acid. Burning the feathers releases sulfur dioxide, the very same kind of gas used by the Spartans at Plataea and Boeotians at Delium. Of course, the Ambracians were not aware of the scientific explanation. They knew only that burning chicken feathers produced a notoriously toxic effect, especially in a tunnel.

Incendiary material

Nature's armory

Weaponizing nature in the ancient world required experience, observation, diabolical creativity, and a willingness to resort to fashioning weapons from whatever was at hand. Wielding weapons based on lethal poisons, volatile chemicals, windborne smoke, unquenchable flames, virulent pathogens, toxic creatures, and unpredictable animals posed dangers not only to the victims but also to the perpetrators themselves. Military training and bravery were useless against these kinds of weapons, which could be wielded secretly or from afar.

In cultures that valued valor and military proficiency, toxic weapons often were viewed as the equivalent of cowardly ambush. Despite a general sense that biological and chemical weapons were unfair, they could be rationalized in certain circumstances. The justifications sound familiar today: When one is outnumbered or facing troops superior in skill, courage, or technology, biological strategies give a real advantage.

Desperate cities under siege resorted to biological options to keep invaders at bay. Generals ordered biochemical attacks out of frustration with long sieges and stalemates or to avoid casualties and the uncertainties of a fair fight. Holy or sacred wars encouraged the ruthless killing of enemy civilians as well as soldiers. Whenever a population was identified as uncivilized, or less than human, there were few qualms about using inhumane weapons.

Contemplating the history of transforming so many destructive natural forces into insidious weaponry is a rather melancholy endeavor. Ancient myth and history shatter the notion that there was ever a time when biological and chemical warfare was unthinkable. But the evidence also shows that doubts about resorting to such weapons arose as soon as the first archer dipped his arrow in poison, and perhaps that is a reason for hope.