Betrayal crushed Sparta's last stand at the Battle of Thermopylae

Outnumbered and undaunted, Spartan warriors and other Greek troops held firm in the face of Persia's might, until treachery brought King Xerxes' fury down upon them in 480 B.C.

In early June of 480 B.C., a mighty Persian army crossed the Dardanelles strait on two pontoon bridges to continue a brutal advance into Greece. Led by the great king Xerxes, the troops were bound for Thermopylae, a narrow mountain pass named for the area’s hot sulfur springs (Thermopylae means “hot gates”). Seated on the east coast of Greece, between the Malian Gulf and the Kallidromo massif, some 85 miles (136 km) northwest of Athens, it is a rugged, craggy landscape of thick brush, thorny shrubs, and steep hillsides, where severe weather—torrential downpours and scorching heat—is the norm.

The dramatically inhospitable four-mile-long pass—the quickest and easiest way to advance from the plains of Thessaly into central Greece—would soon be the site of a legendary battle, an epic, three-day episode that has been memorialized in literature and history as an iconic example of heroic resistance against insurmountable odds.

Facts and figures

Much of what is known about the Battle of Thermopylae (and about the Greco-Persian wars generally) comes from the Greek historian Herodotus, who wrote in the fifth century B.C. Other sources include the Sicilian historian Diodorus Siculus (whose first-century B.C. account was based in part on the earlier Greek historian Ephorus), the ancient Greeks Plutarch and Ctesias of Cnidus, the modern historian George Beardoe Grundy (who performed a topographical survey of the narrow pass at Thermopylae), and to a lesser extent, the Greek tragedian Aeschylus.

No Persian account of the epic battle has survived, and many statistics related to it remain hazy. The number of troops under Xerxes’ command, for instance, is the subject of endless debate. According to Herodotus, the Persian king’s military personnel numbered 2.6 million in all. His contemporary Simonides, a poet, put the number at four million. Ctesias, meanwhile, counted 800,000, while modern scholarly estimates—based on the Persians’ logistical capabilities and constraints during that era—fall between 120,000 and 300,000.

One thing most sources agree on is that the battle was born of both vengeance and ambition. Darius, the father of Xerxes, had been defeated by the Greeks on the plain of Marathon, near Athens, a decade prior—a battle that had conclusively ended the first Persian invasion of Greece.

Ten years later, Xerxes was bent on getting even—and ultimately ahead, by subjugating all of Greece, and thereby expanding the Persian Empire westward.

Xerxes attacks

Standing in his way in the summer of 480 B.C. was a rare confederate alliance of normally fractious Greek city-states—some of which were forced to suspend war with each other in order to face the greater threat from Persia. Athens, which had supported Greek cities in the Ionian Revolt and later defeated Darius in 490, led the coalition with Sparta.

The Athenian politician and general Themistocles led the Greek naval opposition, blocking the Persian fleet at the strait of Artemisium. Leonidas, king of Sparta, commanded the ground forces at Thermopylae: 300 members of his royal Spartan bodyguard, called the hippeis—the subjects of countless books, movies, poems, and songs—along with a lesser-celebrated contingent of 7,000 soldiers in all, including 1,000 Phocians, 700 Thespians, and 400 Thebans.

Leonidas, age about 60, had ascended the throne around 490 B.C., after the previous king, his half brother, Cleomenes, died heirless. The 300 Spartans with him were an elite cadre whom Leonidas had chosen personally. He wanted only soldiers with descendants to accompany him, since he knew there was little chance of them surviving and wanted to be sure that their lineages would continue. Plutarch wrote that when the king was asked before the battle, “What, Leonidas, do you come to fight so great a number with so few?” he replied laconically, “I have enough, since they are to be killed.”

Xerxes’ forces had advanced with ease through the regions of Thrace, Macedonia, and Thessaly, where the overawed inhabitants surrendered without a fight. When Xerxes arrived at Thermopylae in mid-August, he met a stern resistance that was ready for him.

Best-laid plans

Leonidas’s plan was to hold Xerxes at the narrow pass—advantageous terrain that would act as a force multiplier for an army of inferior size. Restricted by the narrow gorge, the Persians would be unable to capitalize on their superior troop numbers, or to use their cavalry. Meanwhile, the Greek fleet could concentrate on defeating the Persian forces in the strait north of the island of Euboea, which lay close by.

That was the plan, but when Leonidas arrived at Thermopylae, he was perturbed to discover that a mountain trail—the Anopaia path—could allow the invaders to circumvent his position. It was too late to change the strategy, however; the fleet was already in position. Leonidas charged the thousand Phocians with guarding the path while his men repaired a wall that protected an opening in the middle of the pass.

Xerxes set up camp near Thermopylae and bided his time for four days. He was convinced that the Greeks, upon seeing his mighty army, would be overcome with fear and retreat. According to Plutarch, he sent a messenger to Leonidas urging him to lay down his arms, but the Spartan king, according to Plutarch, replied, “Molon labe!—Come and take them!”

On the fifth day, the Persian attack began. Their advantage in numbers was of no benefit in this tight space, as Leonidas had anticipated. While they had an abundance of courage and stamina, they were poorly trained for this terrain and lacked heavy weaponry. Their swords were shorter than those of the Greeks, and their shields were smaller. Their bows and arrows also proved useless against the Greeks’ stout shields.

The tight space suited the Greeks, who were used to fighting in a phalanx formation, shoulder to shoulder, presenting a wall of shields to the enemy. It was an opportunity for the Spartans, in particular, to demonstrate their fighting capacity—the fruits of a life given over, body and soul, to the military.

Life among the Spartans

The dominant land power in ancient Greece was known as Lacedaemon in antiquity, but it is better known today as Sparta. Its dedication to military service and discipline gave it a strong advantage over other Greek civilizations—including its chief rival, the philosophical hotbed of Athens—during the fifth century B.C. Unlike Athens, Sparta was famed for its austerity—for its “spartan” character. The Spartans had little interest in intellectual and artistic pursuits (other than patriotic poetry) and were legendary for their intense physical and mental stamina, and their absolute dedication to defending their land. Little remains of their ancient capital of the Laconia region, situated on the Peloponnesus in modern Greece, but the impact of their culture lives on.

Betrayed!

The Greeks pushed back Xerxes’ men time after time, and Persian casualties mounted. Before the first day was over, Xerxes had assembled his best troops—an elite group of 10,000 men under the command of the Persian nobleman Hydarnes. The Greeks dubbed them “the Immortals” because they seemed able to replace casualties immediately, so their ranks were never depleted.

But even they couldn’t subdue the Greeks and were soon forced to retreat. Xerxes, watching the battle from a golden throne in the foothills nearby, is said to have jumped from his seat on several occasions, filled with rage at his troops’ failure.

The next day the Persians attacked and were again unsuccessful. That is when a local Greek shepherd named Ephialtes (whose name has since become synonymous with treachery) handed them the secret to victory. Ephialtes told Xerxes about the Anopaia path, which led around the mountain ridge and ended behind the Greek positions, beside the eastern end of the pass. In exchange for a handsome reward, he promised to show the Persian soldiers the way. According to Herodotus, Xerxes entrusted the advance to Hydarnes and his Immortals, who set out from the Persian camp “about the hour when lamps are lit” and marched all night up the trail.

When Leonidas learned that the Persians had his forces surrounded, he called a council of war. Should the Greeks retreat or stand their ground? Despite the impossibility of their position, Leonidas was firm in his decision: His 300 Spartans, along with a band of Thebans, would stay and fight. His sense of honor and strict military discipline made surrender unthinkable. For a Spartan like Leonidas, there were only two options: win or die. Herodotus adds another detail to the decision: The Oracle of Delphi had foretold that either Sparta would be destroyed by the Persians or its king would die. Knowing this, Leonidas may have believed that his sacrifice would save his city-state.

Death of a leader, birth of a legend

Leonidas ordered the Greek fleet in the strait of Artemisium to abandon its position and ordered most of the men fighting with him on land to leave the battlefield. Those who remained ate to gather strength. According to Diodorus Siculus, Leonidas said, with grim humor, “Have a hearty breakfast, for tonight we dine in Hades!” Ephorus and Diodorus Siculus recount how Leonidas then made an audacious, early assault on the Persian camp. Herodotus’s account, however, describes a Persian offensive. Xerxes didn’t rush to attack as Hydarnes needed time to complete his preparations. The general poured out libations to the rising sun, which was revered by the Persians, and then waited until mid-morning to launch the Persian assault.

Leonidas left the protection of the narrow gorge and took up position in an open area. While dangerously exposed, he was better placed to deploy his men and kill the greatest number of enemies. The Greeks, knowing that death was the only possible outcome, fought in a heedless frenzy. When their spears were broken, they drew their swords and continued to fight.

Finally Leonidas fell. A skirmish broke out around him. The Spartans attacked the Persians and managed to hold them at bay and recover the body of their king. When the defenders saw that Hydarnes had arrived with the Immortals, they fell back and regrouped on higher ground behind the protective wall. Those who still had swords defended themselves; others fought with “fists and teeth.”The Persians eventually broke down the wall and surrounded them, but avoided hand-to-hand fighting. Instead, they finished off their enemies with arrows.

By order of Xerxes, the Theban Greeks who had survived were branded on their foreheads, marked as slaves. Herodotus recounts that Leonidas’s head was cut off, and his body impaled. He was buried in Thermopylae, along with the other soldiers. A stone funerary monument in the shape of a lion was later erected, and the poet Simonides wrote a simple epitaph to all the fallen: “Go tell the Spartans, thou that passest by / That here obedient to their words we lie.”

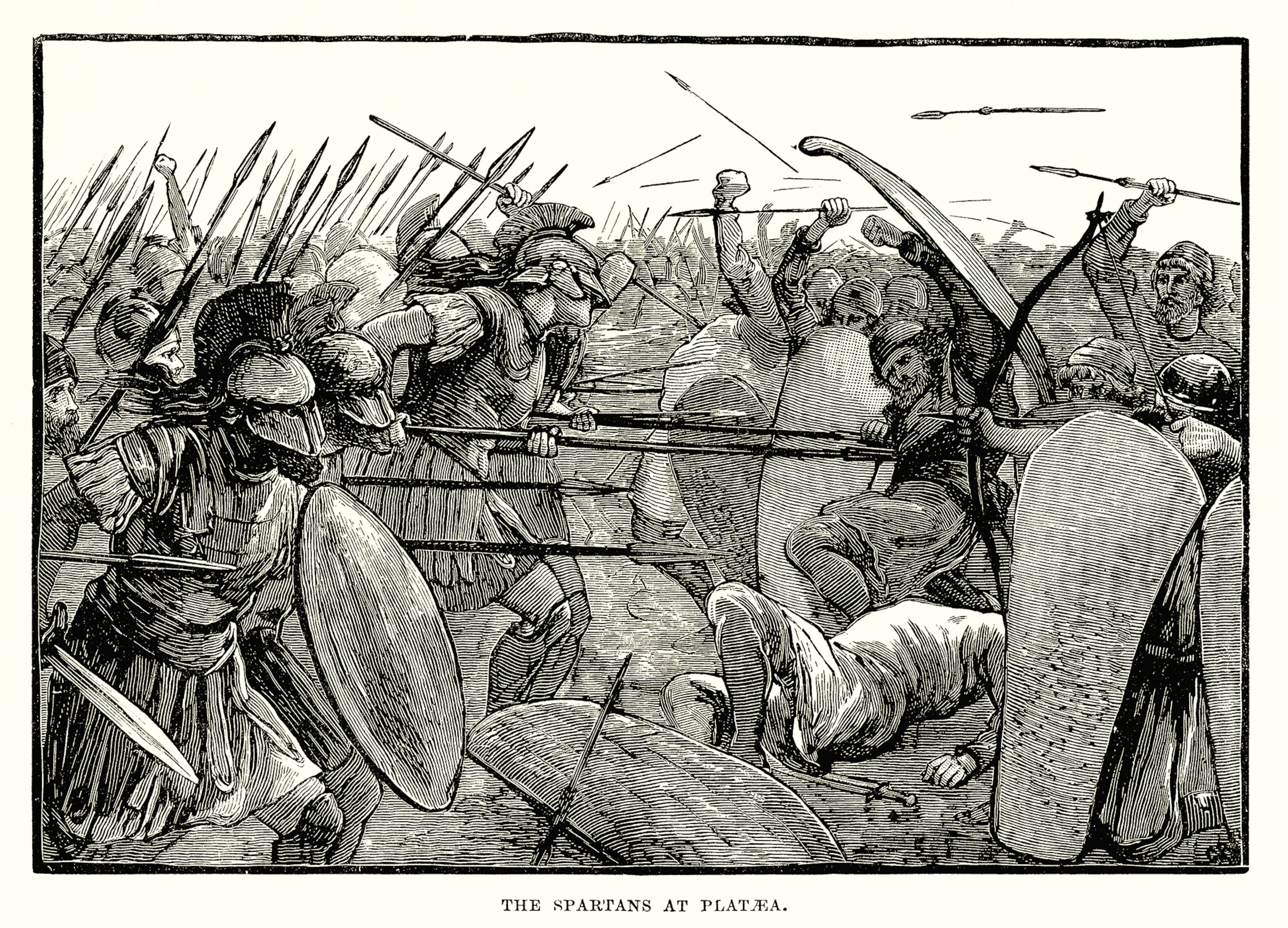

In 440 B.C. the bones of Leonidas were transferred to Sparta. His tomb there can be seen near the modern city of Sparta today. After Thermopylae, the Greeks went on to achieve great victories at Salamis and Plataea where they decisively defeated the Persians. Leonidas and his men had reinforced the prestige of Sparta and raised the morale of all Greeks to continue fighting against Persia. As Diodorus Siculus wrote: “These men, therefore, alone of all of whom history records, have in defeat been accorded a greater fame than all others who have won the fairest victories.”

Never surrender

At Thermopylae, King Leonidas authorized two Spartan soldiers to withdraw from combat because of illness. Eurytus, decided to stay, and was killed in battle. The other, Aristodemus, went home, but when he reached Sparta, he was shunned, marginalized, and deprived of his civic rights. According to Herodotus, “no Spartan would give him fire, nor speak with him; and they called him for disgrace, Aristodemus the coward.”

Xenophon writing in the early fourth century B.C., described how perceived cowards in Sparta were not allowed to share a table, were excluded from games at the gym, and were ignored during choric dances. A coward would have to give up his seat even to a younger man, and no woman would marry him. “[I] am not surprised if in Sparta they deem death preferable to a life so steeped in dishonor and reproach.”

Aristodemus’s torment did not last long. The following year he returned to fight the Persians, this time at the Battle of Plataea. He battled furiously, keen to make up for his “shameful” shortcomings at Thermopylae. “He plainly wished to die,” Herodotus wrote, “and so pressed forward in frenzy from his post.” Aristodemus finally died in battle in an effort to redeem himself.

Learn more

Thermopylae: The Battle That Changed the World. Paul Cartledge. Abrams Press, 2006.