Inside the decadence of Casanova’s Venice

The city in the 18th century was scandalous and dangerous—much like its famous son, whose memoirs detail its reputation as a pleasure capital.

In 1725 a child was born in the Republic of Venice who would grow up to be Casanova, known for his lifelong obsession with the pursuit of pleasure. Wreathed in beauty and splendor, Venice in the 18th century exuded opulence and mystery. It shaped the young man’s worldview and attitudes. Through its celebrations, theaters, casinos, and bordellos, he came to embrace a life of exploration.

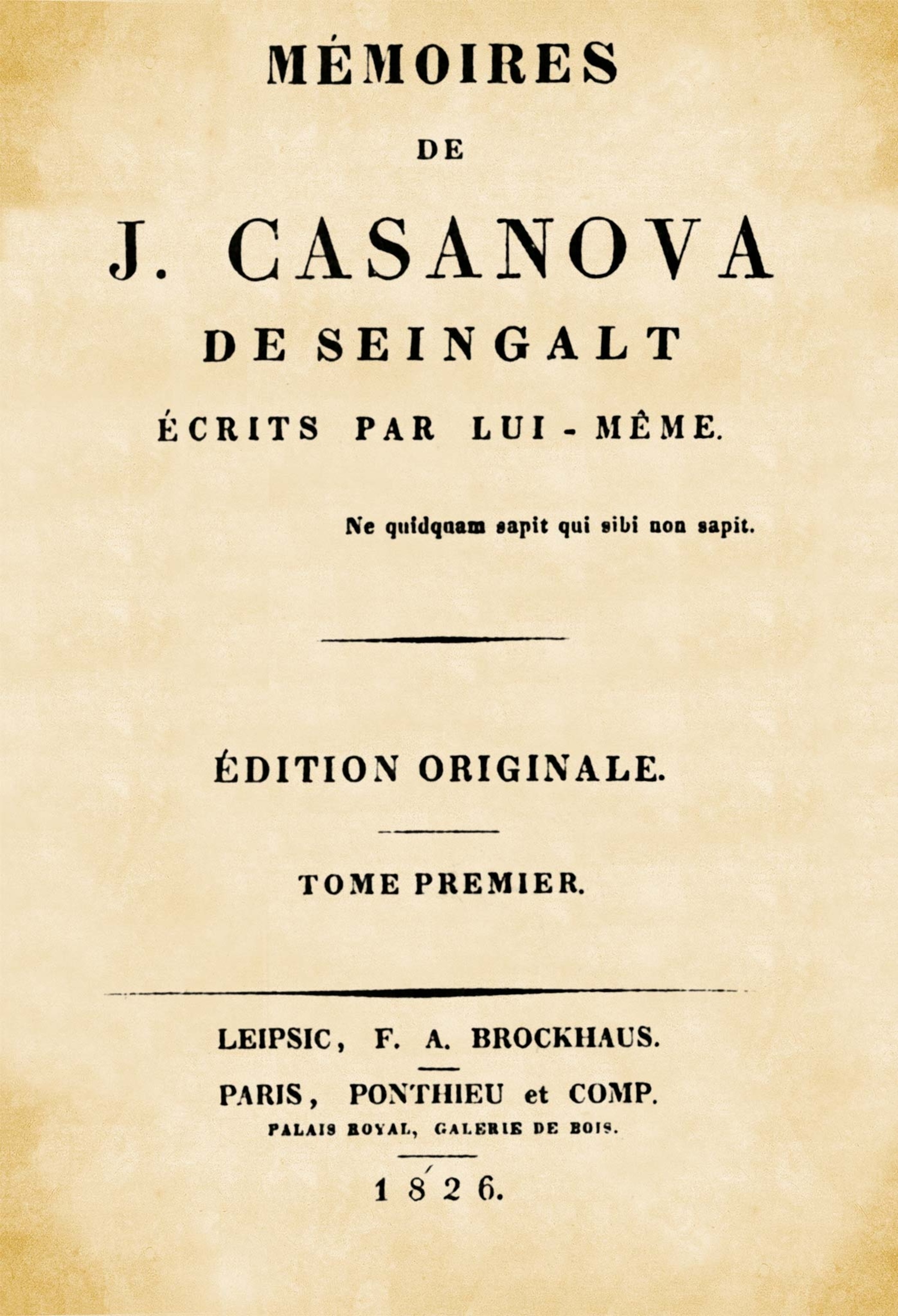

Giacomo Girolamo Casanova was born to two actors in the Venetian neighborhood of San Samuele. Much of what is known about his life came from his own pen; in middle age, he wrote an exhaustive memoir, Histoire de ma vie, which chronicles the first 50 years of his life. His detailed and candid recollections stretch all the way back to his childhood, revealing how the city of his birth shaped his experiences.

His father, Gaetano Casanova, hailed originally from Parma before moving to Venice and joining a theater company in the 1720s. The actor fell in love with a talented teenaged actress named Zanetta Farussi, who was 11 years younger than he. The two married in February 1724. The family home was located behind the San Samuele theater, and the couple would have five more children in the coming years.

In the 18th century an actor’s life often meant working abroad. When Casanova’s parents toured in other countries, little Giacomo was entrusted to his grandmother, Marzia Farussi. The two formed a strong, loving bond, and Marzia would end up mostly raising the young boy as he absorbed the influences of Venice.

One of Casanova’s earliest reminiscences involves his grandmother taking him to a local witch (“une sorciere”) to treat an unyielding series of nosebleeds. His memoirs describe a magic ritual filled with suspense and mystery as an old woman locks him in an enchanted chest, recites some spells, releases him, and anoints him with ointment. The nosebleeds would stop, he was warned by his grandmother, only if he kept the ritual secret. Witchcraft was forbidden by the Catholic Church, and the healer could have faced persecution for her services.

Casanova’s father died when the boy was eight, and the following year he was sent away to school in Padua. His mother would live for another four decades, but Casanova’s connection with her were tenuous; she did not remarry after Gaetano’s death and continued to work in theaters across Europe. When Casanova was 10, she left Venice behind for good, eventually settling in Dresden.

Casanova’s early years in Venice were enveloped by the theater and magic, which both play with illusion and reality. These influences nurtured the young boy’s abilities and interests. Talented at improvisation, he could think quickly on his feet, a skill that served him well throughout his life. The early flirtation with black magic nourished a curiosity about religion, sparking a lifelong exploration of faith and questioning of sacred doctrines—which began with a puzzling career choice for the young man.

Aristocrats and commoners

After graduating from university at age 16, Casanova, to the surprise of his neighbors, returned to Venice as a young abbot, where he was assigned to his home parish of San Samuele. Even for someone like him, with little apparent vocation for an ecclesiastical career, a life in the church did offer an opportunity to climb the Venetian social ladder. Having inherited his parents’ flair for the dramatic, the young abbot’s charismatic and often incomprehensible sermons soon attracted attention.

The cassock, together with the classical studies in which he delighted (he was a great admirer of Horace, whose verses he learned by heart), secured Casanova a tentative foothold in Venetian high society. Though of humble origins, he possessed a sharp wit and refined manners. He embodied the paradox of Venice: a society that celebrated its nobility while depending on the labor of the working classes and the commercial initiative of the bourgeoisie.

What made Casanova’s social advancement possible was that, despite Venice’s class-divided society, there was a natural interaction among the orders. In the streets and squares, nobles mingled with the bourgeoisie and members of the church. The Venetian aristocracy had a certain proximity with working people. People tended to eat similar dishes whatever their social class: macaroni, grilled fish, stewed eels, red mullet, and other seafood.

Casanova saw the class barrier as a porous one and waited for his moment to infiltrate and rise through their ranks. Young and restless, Casanova soon gave up being an abbot; he wrote: “My love [affair] proved fatal to me, because from it sprang two other love affairs which, in their turn, gave birth to a great many others, and caused me finally to renounce the Church as a profession.” He spent a short time enlisted in the army but returned to Venice and started to earn his living as a violinist.

Talented, charming and with an irrepressible spirit, he may still have passed unnoticed by history had it not been for what happened on the day he witnessed a red-robed senator having a heart attack in the street. Casanova hurried to the man’s aid, helped him home, and stayed at his side even after doctors and friends had arrived. The patient turned out to be Matteo Bragadin, a politician and member of the most established circle of Venetian nobility.

Bragadin recovered and claimed he owed his life to the young man who had come to his aid. Casanova capitalized on this unexpected break and started to draw Bragadin and his circle of friends under his influence. He wrote: “I spoke like a learned physician, I dogmatized, I quoted authors whom I had never read.” He performed magic tricks that he’d learned from his grandmother.

Casanova’s interest in religion wowed Bragadin’s circle with his knowledge of the cabala, the study of which was in vogue in the city at the time. In 18th-century Venice rationalism and occultism went hand in hand, and Casanova used his intellect and charm to further his social ascent.

Mentor and mentee

Bragadin was so impressed that he took the young man under his wing. Casanova, who was genuinely fond of Bragadin, moved into his house and found himself more securely established in the upper echelons of Venetian society, with his bills paid and the possibilities of an aristocratic life before him. By now Casanova was tall, attractive, and cultured. He was at ease with people of every background—the common people, the clergy, and now also the nobility. It was a rare quality and one that made him highly prized in Venetian society.

Casanova also had a disquieting sense of being kept on the fringes of the circle he moved in, like a jester exploited for his wit but never fully accepted. He was frustrated at being left out of hierarchy based on birthright and writes in his memoirs: “Respect the man that defines nobility in a new way, which you cannot understand. With him nobility is not a series of descents from father to son; he laughs at pedigrees.”

Love affairs

Casanova is perhaps most famous for his seductions, sexual scandals, and love affairs. His memoirs proudly describe his encounters with countless girls and women in great detail; many of these accounts are quite shocking to modern readers. Casanova biographer Leo Damrosch recently wrote,“His career as a seducer, already notorious in his own time, is often disturbing and sometimes very dark.” Many of his encounters would be classified today as immoral at best and criminal at worst, making it imperative to read his memoirs with a critical eye. The women’s voices are largely absent from his memoirs, allowing the reader to hear only his side of the story.

Venice’s moral code was quite separate from the rest of Europe in the 18th century, which may stem from its unique place in European history. Unlike many other cities, Venice was an independent republic for centuries and developed its own attitude toward sexual pleasure and enjoyment. By the 18th century it had developed quite a reputation as a pleasure capital, a popular stop for many young men on their so-called grand tour of Europe. Although on the surface Venice was governed by rigid Catholic mores, in reality it encouraged sexual exploration, especially for its male citizens.

For men, not having a lover was seen as a cause for embarrassment—and in this cardinals and prelates were no exception. Almost all male aristocrats were involved with very young female courtesans, many of whom would go on to marry from among the nouveau riche. Not even the nuns were left out of these liaisons: One of Casanova’s great love affairs was with a nun he calls “MM” in his memoirs. In fact, Casanova was not MM’s only lover. She was already involved with a religious French diplomat, and Casanova organized a tryst for the three of them plus another woman who was also an ex-lover of Casanova.

Casanova was in his element in promiscuous Venice. He spent a lot of time in and around Venice’s theaters, which he knew well, having been born into an acting family, and which were a good place to meet women. Venetian theaters at the time were rowdy, sociable places, with a hubbub from both aristocrats in their boxes and commoners in the stalls.

Casanova would later say of his very young self: “Still very innocent, I felt some disinclination towards women, and I was simple enough to be jealous of even their husbands.” That persona was soon overlayed with another that was more confident and predatory yet retained a lingering sense of class anxiety. As Casanova enjoyed the theaters of Venice in pursuit of sexual liaisons, he found himself pulled between his humble roots and the high society he was now frequenting. He still felt more comfortable with nonaristocratic women and especially if they were young; 14- to 18-year-olds were of particular interest.

The one who got away

Carnival and casinos

Carnival, an integral part of life in Venice, was a setting that lent itself to both social mobility and sexual promiscuity. In the 18th century Carnival began in October and lasted for at least five months. Masked revelers filled the streets giving everyone license to impersonate anyone—a boon for a trickster like Casanova. He writes extensively in his memoirs about the disguises he wore that allowed him to slip anonymously around the city. Among the aristocrats, his costumes made him feel less inadequate. Among the ordinary people, they lent him an air of mystery. Disguise would turn out to be key to many of his adventures.

The hub of Carnival festivities was St. Mark’s Square. There, comedies, concerts, and plays took place on improvised stages, as well as wrestling and boxing matches. Astrologers and charlatans eager to exchange cash for a fortune told mingled with the revelers. There were grotesque spectacles in the name of entertainment: bears secured to a pole by a chain through the palate and cage fights between angry cats.

Casanova, like many other Venetians, was obsessed with gambling and suffered dire consequences for his addiction. Gambling took place in ridotti, buildings that were reserved for games of chance. These casinos could range from dingy dives to elegant palazzos, and Venetians of all classes enjoyed them. An example of the latter was the ridotto opened in 1638 by the aristocrat Marco Dandolo. It boasted 10 or 12 gambling rooms equipped with gaming tables. There the select clientele maintained absolute silence as they played.

In Venetian high society, where most people gambled, entire fortunes could vanish overnight. Casanova, a stranger to moderation, ran up huge gambling debts that proved too much for even the generous Bragadin to settle. Casanova incurred more and more debt to pay his dues and was not averse to “borrowing” from the women he seduced.

Scandal, prison, exile

Casanova continued with this lifestyle for years, but there was a limit to how much debauchery his circle would accept, even with Bragadin’s protection. Venice was governed by an oligarchy known as the Council of Ten, an assembly of 10 aristocrats elected annually who had almost absolute power. When it felt like it,this government was capable of intimidating anyone, even the wealthy Bragadin.

The punishments meted out by the Ten could be merciless. Bragadin had long warned his protegé about stirring up the ire of the Ten, but Casanova ignored him. He knew he hadn’t broken any laws, but he miscalculated by ignoring the fact that he was still technically a commoner against whom many aristocratic husbands held a grudge.

At age 29, Casanova was seized one morning and, without further explanation, forced to cross the Bridge of Sighs and locked up in the Piombi prison. Luckily for him, this jail was reserved for high-ranking prisoners; he would have faced a far worse fate had he ended up in the Pozzi, where the cells were just below sea level and prisoners served their sentences knee-deep in seawater.

Casanova was not informed of the exact charge against him or told how long he would be held. His case would never be brought to trial. All he knew was that the authorities alleged that “when [he] lost money at play, on which occasion all the faithful are wont to blaspheme, [he] was never heard to curse the devil.” He was also accused of“eating meat all the year round” and “of only going to hear fine masses.” With no prospect of being released, Casanova made a daring escape that involved drilling through the lead ceiling of his cell and, after some heart-stopping moments, walking free under the unsuspecting gaze of the guards.

Palace prisons

After the escape, Casanova spent 18 years outside of Venice, seducing and deceiving his way across Europe. By the time he was finally able to return home, he was a middle-aged man. Venice had changed, and Casanova missed the wild society events he had experienced in his 20s, the nonstop Carnival and balls on the Grand Canal. He would be exiled again in 1783 and spend the last years of his life working on his memoirs, which begin with a frank admission: “I will begin with this confession: whatever I have done in the course of my life, whether it be good or evil, has been done freely; I am a free agent.” At age 73, Casanova died in 1798, a year after the Republic of Venice fell to Napoleon Bonaparte.

Pens and prose