Standing Tall: Egypt’s Great Pyramids

Pharaohs Khufu, Khafre, and Menkaure built their massive tombs to last. For more than 4,000 years, the Pyramids of Giza continue to amaze while holding on to their many secrets.

Amelia Blanford Edwards was one of a stream of European travelers drawn to see the wonders of Egypt at the close of the 19th century. In her 1877 book, A Thousand Miles Up the Nile, she writes of the hot drive to the edge of the desert, until “the Great Pyramid, in all its unexpected bulk and majesty, towers close above one’s head ... The effect is as sudden as it is overwhelming. It shuts out the sky and the horizon. It shuts out all the other Pyramids. It shuts out everything but the sense of awe and wonder.”

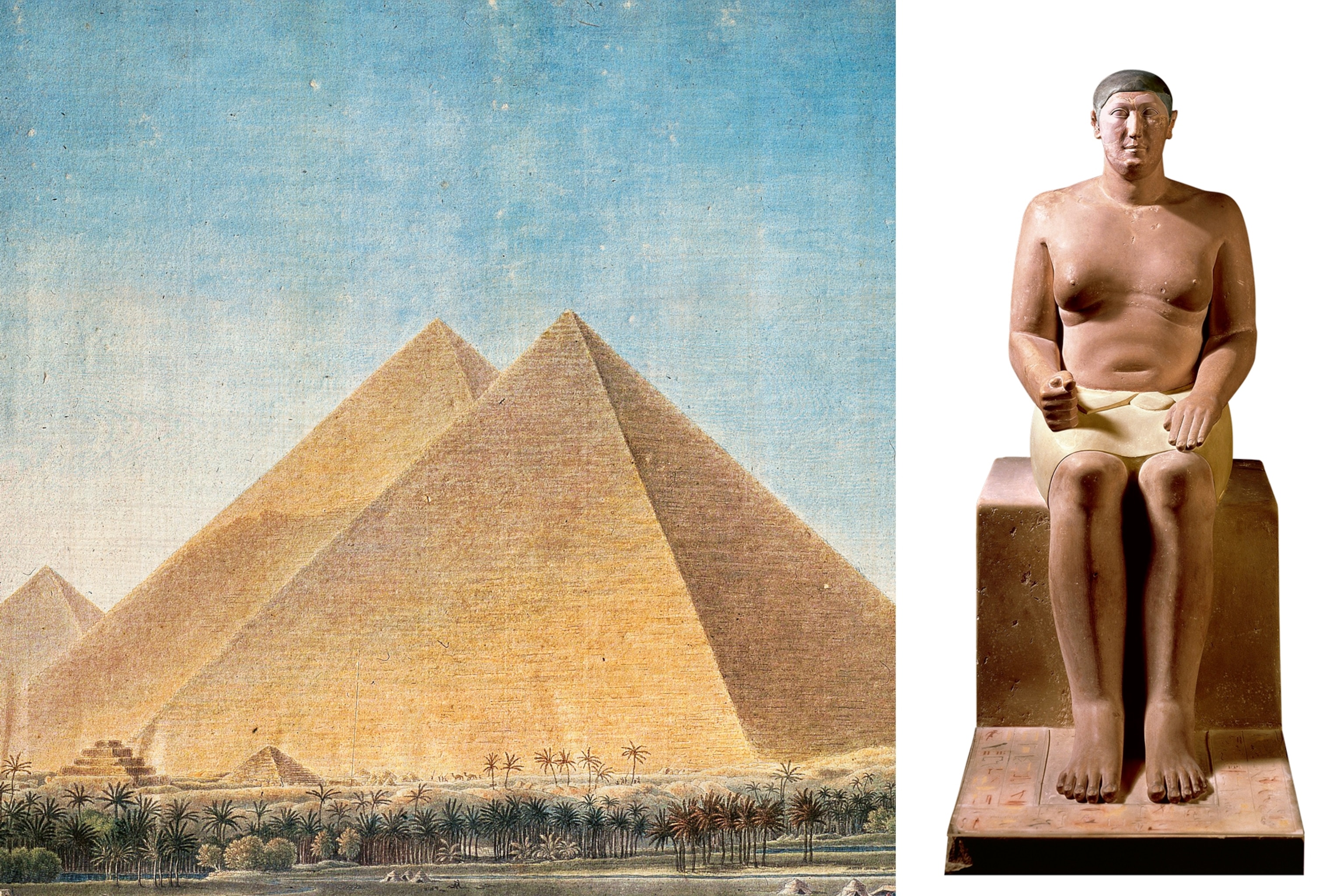

Most modern travelers would probably reach for similar words to pinpoint the sublime thrill of seeing the Pyramids at Giza in person today. They are so iconic, so astonishingly ancient, that it is hard to imagine that 4,600 years ago the plateau where they stand was a desolate, dune-covered wilderness where a scattering of tombs lay under the burning Egyptian sun. Along with the enigmatic Sphinx and other smaller tombs and monuments, Giza has three principal pyramids: Khufu (originally 481 feet high, and sometimes called Cheops, or the Great Pyramid); Khafre (471 feet); and Menkaure (213 feet). Emerging out of the complex dynastic needs of Egypt’s 4th dynasty, they are the triumphant product of one of the most daring and innovative engineering projects the world has ever known.

The kings of the 4th dynasty ruled Egypt from around 2575 to 2465 B.C. Presiding over the golden age of the Old Kingdom, their center of power was the sophisticated Nile-side city of Memphis, about 15 miles south of Giza. The dynasty’s second king, Khufu, ruled during a period of relative peace in Egypt, although the Greek historian Herodotus later depicted him and his son as cruel and proud.

Khufu’s architects and engineers embarked on a project that transcends any other structure in the Bronze Age. Its completion utterly transformed the plateau. Khufu had selected it, in part, to distance himself from the magnificent pyramids built by his father, Snefru, in Dahshur, another necropolis near Memphis. Several other factors also made it an ideal site. The high plateau allowed greater visibility for the pyramid. It was near Heliopolis, basis of the cult of the sun god Re. Since there were already some tombs in Giza, the land had already been sanctified and so was fit for a pharaoh’s tomb of a stature never seen before, or surpassed since.

After Khufu’s death, his son Redjedef ruled for a short time and began work on a tomb in Abu Ruwaysh that was never finished. The next pharaoh, his brother Khafre, built a pyramid—as well as the Great Sphinx, some scholars claim—in Giza. The next generation followed the same pattern: Baufre, son of Redjedef, built his tomb outside of Giza, while Menkaure, Khafre’s son, built his in Giza.

Each pharaoh who built in Giza did so in accordance with some simple rules that harmoniously ordered the three funerary complexes on the plateau: the facade of Khafre’s high temple is aligned with the western face of Khufu’s pyramid. And the facade of Menkaure’s high temple is aligned with the western face of Khafre’s pyramid. At the same time, the imaginary line that roughly joins the southeast corners of the three pyramids points toward the temple of Re in Heliopolis.

Timeline: Fathers and Sons

circa 2550 B.C.

Khufu, second king of Egypt’s 4th dynasty, begins work on his pyramid. When complete, the massive tomb will measure 481 feet high, the biggest pyramid ever.

circa 2530 B.C.

Redjedef, Khufu’s son, holds power for only a few years. He commissions a pyramid north of Giza at Abu Ruwaysh, but the structure is never finished.

circa 2520 B.C.

Khafre, another son of Khufu, commissions the second pyramid at Giza. Although it is slightly smaller than Khufu’s, it sits on higher ground, making it look taller.

circa 2490 B.C.

Menkaure, after succeeding his father, places his pyramid next to Khafre’s and his grandfather’s. The contents of all three tombs will be looted.

Who Built the Pyramids?

Herodotus claimed that construction of the Great Pyramid—today calculated at over six million tons of stone—was carried out using slave labor. It is now known this building was undertaken, in fact, by paid Egyptian laborers. The notion that Egyptian monuments were built by slaves—such as the plight of the Hebrew slaves recounted in the biblical book of Exodus—seems to have had currency in the ancient world.

Such colossal building projects would have left some kind of archaeological trace, and so it was amid huge excitement that in 1999 archaeologists started to uncover the village housing of the workmen who built the two later pyramids of Khafre and Menkaure. This followed the discovery of the workers’ cemetery in 1990, which was divided into upper and lower parts according to the rank of the deceased.

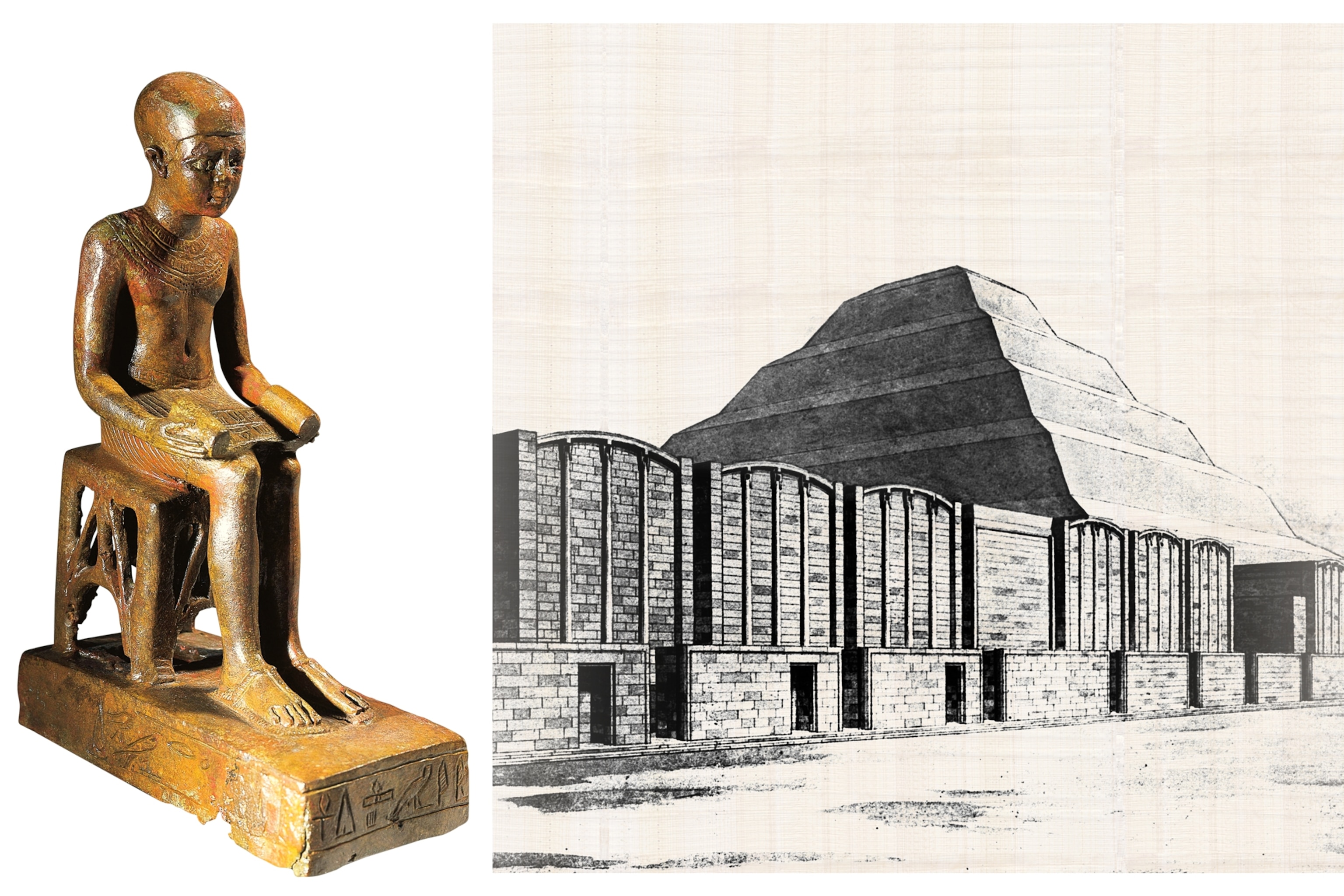

Imhotep, The Builder God

Imhotep was one of the leading minds of the 3rd dynasty, not only because he was the architect of the first pyramid to be built, the Saqqara step pyramid, but because he held senior positions in all areas of Egyptian society: religious, political, economic, and artistic. He also built the pyramid of Djoser’s successor, Sekhemkhet. He was later deified as the god of medicine throughout Egypt in the Late Period.

Both village and cemetery offer archaeologists a mine of valuable data about the conditions in which the two smaller pyramids of Giza were built—data that, in turn, gives a working hypothesis as to the construction of the pyramid of Khufu. A study of workers’ bones shows that the work was backbreaking—sometimes literally. Yet these laborers, far from being slaves, were privileged civil servants, and beneficiaries of a number of enviable perks.

Analyses show they enjoyed a protein-rich diet, practically unheard of among the rest of the Nile Valley’s inhabitants. Evidence that broken limbs and fractures had been set correctly strongly suggests adequate medical care was provided. One of the skeletons in the cemetery had a leg amputated so precisely that experts estimate that the patient lived for some 20 years after the operation. The discovery of the workers’ village has also enabled archaeologists to debunk another of Herodotus’s somewhat fanciful claims: that 100,000 people built Khufu’s pyramid. In fact, the village seems to have had a maximum capacity of 20,000 people, of whom perhaps half were dedicated to construction at any one time.

Putting It Together

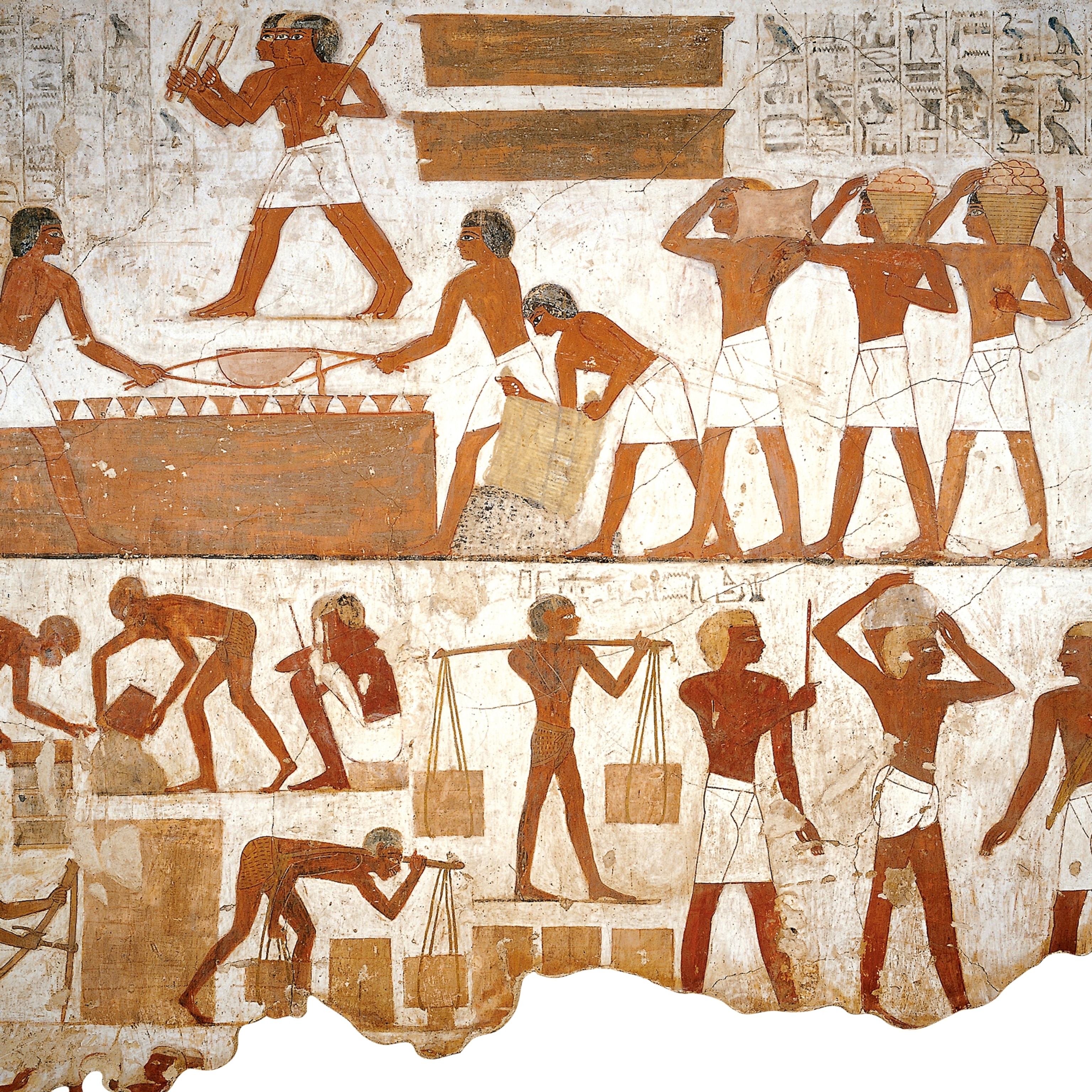

The daunting challenges of building such a structure, and efficiently marshaling thousands of workers, required meticulous planning. Scribes set about calculating the number of blocks that would be required to build a pyramid with the selected gradient—in the case of Khufu, the angle of the sides with the ground is 52 degrees—the kind of mathematical problem recorded in Egyptian mathematical papyri, and at which Egyptian civil servants excelled.

Graffiti and inscriptions at the site have also enabled scholars to piece together telling facts about life on this colossal construction site. Blocks found with dates from all seasons in the Egyptian calendar suggest the pyramids were built year-round and not just when the Nile was in flood.

Hemiunu, The Portly Architect

It is not known who designed the Great Pyramid, but the man responsible for supervising its complex construction was Hemiunu, Khufu’s nephew, a senior civil servant who acted as the pharaoh’s vizier. Despite the mystery surrounding Giza, Hemiunu himself was a flesh-and-blood man, as shown by his decidedly lifelike—and fleshy—statue, found in his tomb in Giza’s west cemetery.

There are many types of pyramids and not all were built in the same way. The lowest stones in Egypt’s first ever pyramid—Djoser’s step pyramid in Saqqara, built the century before Khufu’s—are bricks. But as construction progressed, and engineers became more confident, they used larger blocks. The largest at Giza, weighing three tons, were those used to build Khafre’s pyramid.

Much of the stonework in the Giza Pyramids came from a quarry barely half a mile to the south of the Great Pyramid of Khufu. The white limestone that once formed the outer casing had a longer journey to Giza, moved by boat along the Nile from Tura, eight miles away. When he was working in Karnak in the 1930s, the scholar Henri Chevrier discovered that a five-ton block can be dragged horizontally along a wet clay track by just six men. As pictures found in tombs have shown, blocks of that size were also sometimes pulled by oxen. The ramps by which they were raised onto the pyramid structure have also been depicted on the decoration of some tombs, and there is archaeological evidence for such ramps at Giza itself.

The geometry of a pyramid helped overcome the logistical problem of raising massive stones: As much as 40 percent of a pyramid’s volume is concentrated in its bottom third. The raising of stone blocks by means of a ramp beyond the lower third of the structure was, however, a major challenge, and it is still not fully known how the Egyptians solved the problem. One solution would have been to use the building’s inner step structure—visible today, since the outer casing stones have long disappeared—because then the blocks would only have had to be raised a little at a time, in the same way a heavy object can be eased up a staircase.

The rows making up Khufu’s pyramid are slightly more than two feet high on average. So it is highly likely that, given sufficient manpower, levers could be used to raise large blocks into position—and so on, until the construction reached completion in the form of the pinnacle, known as the pyramidion, which historians believe was put in place in the course of a solemn ceremony.

The pyramidion atop Khufu has long been toppled, but is thought to have been of white Tura stone. It capped a total of two and a half million stone blocks, making it one of the most massive buildings on the planet, the only one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World that is still standing.

Hunting for a Pharaoh’s Face

He ordered the building of one of the biggest monuments in the world, one which bears his name 4,500 years after he ruled. His name appears on documents and on the few reliefs that remain on the entrance path to his funerary complex. Yet until a few years ago, there was only one tiny representation of Khufu, the man who built the Great Pyramid of Giza: an ivory carving just three inches high (above), an artifact considered—in a supremely ironic twist—as the smallest piece of Egyptian royal sculpture ever discovered.

Recently, however, some specialists have suggested that a pair of limestone and granite stone heads from the Old Kingdom might be portraits of Khufu—a theory contested by other historians. Yet another hypothesis may give Khufu the biggest boost of all: According to Giza expert Rainer Stadelmann, the face of the Great Sphinx at Giza is not Khafre—as some scholars have argued—but Khufu himself, in divine form, protecting his pyramid.