How the Declaration of Independence wooed Americans away from Britain

Cutting ties with a king might have seemed like "Common Sense" in the 1770s, but the desire was not unanimous among the colonists—until the Declaration convinced them otherwise.

In perhaps the most famous words from the Declaration of Independence—“We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness"—the founders of the United States define the rights that a good government must secure and protect. If these rights were trampled, then that was grounds for divorcing the tyrant, but not everybody was keen to break up with Britain and King George III.

Slowly but surely, the Founders had to make a case for freedom, convincing reluctant individuals and colonies—even after hostilities had broken out. The Declaration of Independence is the culmination of that effort, carefully explaining, point by point, why the colonists had no choice but to separate from "Mother England."

Setting the stage

The Declaration of Independence is a relatively short document, little more than 1,300 words, but it was the result of a long struggle, one that had been simmering between Britain and its North American colonies for more than a decade. By 1775, tensions had risen between the Americans and the British in colonial America, resulting in the first battle of the Revolutionary War at Lexington and Concord that April.

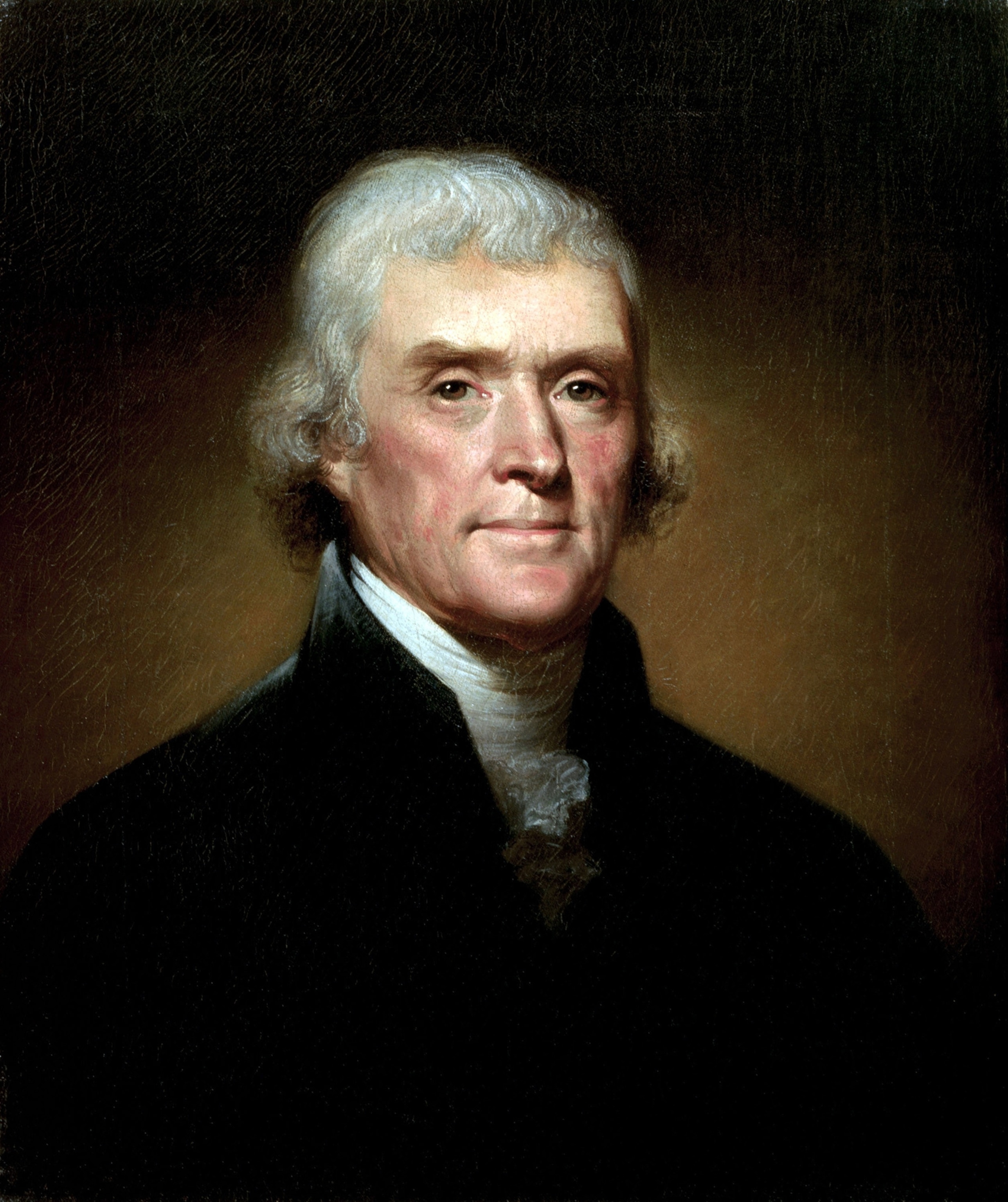

In those early days of the Revolution, few Americans wished to completely break away but rather wanted their rights as British citizens to be protected. They wanted their voices heard by Parliament as well as the king. In fact, those who supported independence, including Thomas Jefferson and John Adams, were considered dangerous radicals.

King George III dug in, ordering more troops to fight the rebels to put down the insurrection. In August 1775, he declared his American subjects were “engaged in open and avowed rebellion.” In May 1776, Congress learned the king had negotiated with Germany to hire mercenaries to fight in America. Americans began to realize their mother country was acting like a tyrant.

(Pulling down statues is as American as apple pie. Just ask George III.)

Then, in January 1776, political activist and philosopher Thomas Paine published Common Sense, arguing that independence was a “natural right” and the colonies’ only course of action. Buying it by the thousands, the colonists came to realize they were fighting a losing cause—there could be no reconciliation. They needed to establish their sovereignty. The stage was set for the penning of the Declaration of Independence.

Revolutionary debate

The efforts ramped up on June 7, 1776, when the Continental Congress met at the Pennsylvania State House (now known as Independence Hall). Virginia’s Richard Henry Lee introduced his resolution beginning: "Resolved: That these United Colonies are, and of right ought to be, free and independent States, that they are absolved from all allegiance to the British Crown, and that all political connection between them and the State of Great Britain is, and ought to be, totally dissolved."

In the debate that followed, it became clear that some states were “not yet ripe for bidding adieu to the British connection but they were fast ripening,” as one delegate put it. To give them time to ripen, the Congress delayed a vote on the resolution until July 1 and called a recess. It also appointed a five-member committee to draft a document explaining the reasons for declaring independence should Congress so decide.

(5 Surprising Things You Didn’t Know About Margaret Thatcher)

The declaration committee—John Adams of Massachusetts, Roger Sherman of Connecticut, Benjamin Franklin of Pennsylvania, Robert R. Livingston of New York, and Thomas Jefferson of Virginia—assigned 33-year-old Jefferson, who “had the reputation of a masterly pen,” the task of writing the document. Years later, John Adams, a committee member, said he had passed the assignment to Jefferson because “a Virginian ought to appear at the head of this business.” Also, Adams admitted, he himself was “obnoxious, suspected, and unpopular.”

(See these amazing artifacts from the Revolutionary War.)

Making the case for freedom

Jefferson knew the works of Enlightenment philosophers like John Locke and scientific pioneers like Isaac Newton, and he pulled their ideas into his composition, along with those from the Virginia Declaration of Rights.

He composed five sections, including an introduction that states the reasons the colonies must depart the British Empire. Jefferson explains how the inalienable rights of citizens (who, at the time, did not include women, Native Americans, and African Americans) were being trampled by King George III. The preamble concludes: “[A] long train of abuses and usurpations … evinces a design to reduce [a people] under absolute Despotism, it is their right, it is their duty, to throw off such Government, and to provide new Guards for their future security."

The body contains two sections, the first of which provides evidence of the king’s “long train of abuses and usurpations” upon the colonies and the second stating how the king refused to address the colonies’ grievances. The document concludes that “these United Colonies are, and of Right ought to be free and Independence States; that they are Absolved from all Allegiance to the British Crown, and that all political connection between them and the State of Great Britain, is and ought to be totally dissolved.”

At times, Jefferson’s prose soared, but he never swayed from his true purpose: to build, in good 18th-century style, a legalistic argument against tyranny. After Adams and Benjamin Franklin both made minor edits to Jefferson’s text, it was ready to be presented to the Continental Congress.

Path to independence

Congress reconvened on July 1, 1776. Twelve of the 13 colonies adopted the Lee Resolution for independence the following day (New York's delegates abstained, since their instructions were to only pursue reconciliation with the king). Congress then turned to Jefferson’s declaration, which they debated, considered, and revised through July 3 and late into the morning of July 4. Substantial editorial revisions were made, including condensing the final five paragraphs (much to Jefferson’s dismay), but the preamble remained more or less intact.

Congress approved the final draft on July 4.

The shop of John Dunlap, official printer to the Congress, printed the first copies of the Declaration of Independence—it’s believed about 200 copies were produced, about 25 of which exist today. Riders subsequently carried broadsides of the document through the colonies. On July 8, church bells rang out in celebration, and Jefferson’s words echoed in public gatherings. On July 9, New York reversed its decision, permitting its delegates to join the other colonies in favor of breaking with Britain.

Roar of revolution

An official version of the declaration was embossed on parchment and, on August 2, signed—the first and largest signature was that of the president of the Congress, John Hancock of Massachusetts. Not every man who was present at the July 4 meeting signed the document on August 2. Historians believe seven of the 56 signatures were placed later. Two delegates did not sign: John Dickinson of Pennsylvania and Robert R. Livingston of New York.

Nevertheless, these Americans were now publicly and irreversibly enemies of the empire they had until so recently embraced. “We are in the very midst of a revolution,” John Adams proclaimed, “the most complete, unexpected and remarkable of any in the history of nations.”

(How inoculation saved the U.S. War for Independence.)

The Declaration today

The Declaration of Independence, faded but still visible, can be seen today beside the U.S. Constitution and the Bill of Rights in the echoing, semicircular Rotunda for the Charters of Freedom in the National Archives museum in Washington, D.C. The documents are preserved within a state-of-the-art case that protects them against air and moisture. At night and in the event of an emergency, the documents are retracted into a deep vault for safekeeping.

To learn more, check out Founding Fathers. Available wherever books and magazines are sold.