Who was the Native American mystery woman of San Nicolas Island?

Her castaway tale captured 19th-century imaginations and inspired the novel 'Island of the Blue Dolphins.' Scholars today are diving deeper into her people's history in California's colonial past.

When otter hunters returned to Santa Barbara from California's most remote island in 1853, they carried more than cargo and a diverse crew. Also aboard was a 50-year-old woman—a passenger who spoke a language they could not understand. More astounding, she apparently had spent 18 years alone on the island.

A striking, romantic figure, the woman soon became an object of national fascination and romantic speculation— fueling tales of a surviving castaway. “Undoubtedly,” a correspondent wrote, “she is the last of her race.”

Nameless. Silent. Courageous. Her story had all the makings of a fascinating historical yarn—and inspired not just lengthy newspaper articles but also Scott O’Dell’s Newbery Medal–winning Island of the Blue Dolphins, a staple of elementary school curricula nationwide.

But the details of the Lone Woman’s life, historians and archaeologists are now discovering, were built on a foundation of shifting sand. Today scholars believe that nearly everything they thought about the enigmatic figure was wrong—and that the Lone Woman was anything but alone.

(Explore 13,000 years of human history on California's Channel Islands)

Channel Islands castaway

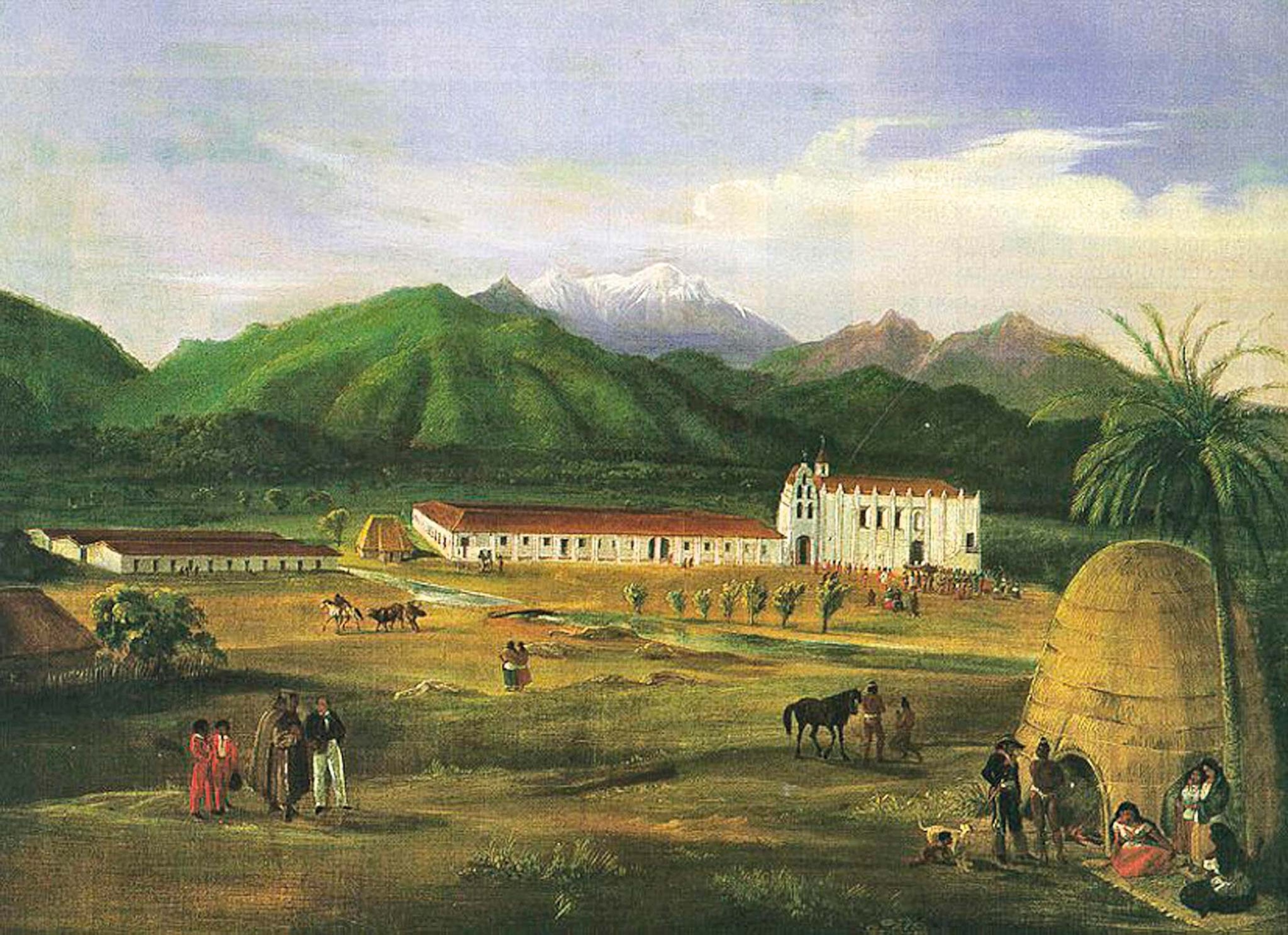

About 60 miles off the California coast in chilly waters, San Nicolas Island is the most remote of the Channel Islands, an archipelago with a tormented history of Indigenous use and environmental exploitation. Today five of the eight islands make up the Channel Islands National Park, but San Nicolas is used for weapons testing by the U.S. Navy. In the 19th century it was home to Native Americans who had inhabited it for thousands of years. Spanish colonizers dubbed them the Nicoleño.

Details of the Lone Woman’s life, historians and archaeologists are now discovering, were built on a foundation of shifting sand.

The secluded, dune-covered island was largely ignored by early European explorers, who did little more than name it. In the early 19th century, though, that changed—and so did the fate of its roughly 300 Native inhabitants. Beginning in 1814, Russian otter hunters landed on San Nicolas in search of valuable furs. Mayhem ensued. Contemporary documents suggest that in retaliation for the murder of one of the hunters, the group massacred up to 90 percent of the Nicoleño. When in 1835 the remaining Nicoleño boarded a schooner to Los Angeles, the island’s abundant otter population had been hunted nearly to extinction.

(The surprising way sea otters enhance ecosystems.)

The Nicoleño had left their ancestral home. But one remained. Cut to 1853, when newspaper accounts of the discovery of a “female Robinson Crusoe” began to flood out of California. After years of rumors that someone still lived on the island, an American-led trapping expedition found and “rescued” a resourceful woman in a greenish cormorant-feather skirt. She had lived in both a whale bone hut and a cave and subsisted on island wildlife—seal blubber, plant bulbs, abalone, birds.

Though the woman apparently enjoyed her new life in an adobe home in Santa Barbara, her trip to the mainland was lonely too. The communication barrier seemed insurmountable and mainland diseases took their toll. She died within seven weeks of her “rescue.” Before her death, a Catholic missionary christened her “Juana Maria.”

That story—one of wild solitude, natural beauty, native grit, and the tragic fate of the “noble savage,” caught the attention of author Scott O’Dell, whose 1960 Island of the Blue Dolphins is based on the story. The book fictionalized the Lone Woman as the resilient teenager Karana, creating a portrait of a girl’s coming of age in the face of overwhelming difficulty.

(See America’s parks with Indigenous peoples who first called them home.)

based on a true story

Fact finding

It would seem there’s no more to learn about the woman who, stranded by herself on her home island, hunted, fished, and withstood the elements as her people died out. But recent research suggests there’s more—much more—to the story.

In the 20th century archaeologists began to return to San Nicolas in search of more information about Juana Maria and her people. They would find up to 500 archaeological sites on the island. Some, like the remnants of a whale bone hut, do appear to be linked to the Lone Woman herself, while others provide more documentation of the rich history of the Nicoleño. Still others refute nearly every dramatic highlight of Juana Maria’s supposed solitary life on San Nicolas Island.

Archaeological and genetic evidence shows two waves of Nicoleño on San Nicolas Island, which was occupied for roughly 8,000 years. Their culture seems to have been closely linked to the ocean—a testament to the lack of land animals. Remnants include everything from bone arrowheads to a cave marked with images of whales. The tribe appears to have coexisted peaceably with a variety of visitors—hunters from Mexico, Russia, Alaska, and elsewhere—from the 17th century on.

(North America’s Native nations reassert their sovereignty: ‘We are here’.)

Independent historical researcher Susan Morris fell in love with the Lone Woman in fourth grade after she read Island of the Blue Dolphins in school. “I was completely inspired by her lessons of courage and resourcefulness,” she says. Morris is one of a team of researchers who has spent years dismantling the myths and misunderstandings that still surround the Lone Woman’s place in history.

Tracing the Lone Woman's roots

Despite previous scholarship and abundant secondary sources, says Morris, it was clear 19th-century chroniclers had bypassed a variety of sources—the hunters who visited San Nicolas, the Native people who interacted with the Lone Woman during the last months of her lifetime, the missionaries who baptized her, the island’s archaeological record, the Nicoleño themselves. Their motivations are lost to time, but one suspects the compelling tale of a lone castaway might have clouded their collective judgment.

When taken into account, those historical sources reveal a very different story. The team traced the Nicoleño who left the island in 1835 and learned that at least seven of them had settled in Los Angeles, where they thrived. At least one of them, dubbed Tomás, outlived the Lone Woman, disproving the romantic portrayal of her being the “last of her tribe.”

(How Tecumseh fought for Native lands—and became a folk hero.)

Claims that no one could communicate with her were inaccurate too. Linguists have now traced the four remaining words of her dialect to the Takic linguistic branch. (Santa Barbara’s Native population spoke Chumash, which explains their difficulty understanding her attempts to communicate with them.) Eventually, the woman did manage to speak with people who could comprehend her. “She was trying to share her story,” Morris said in a 2018 lecture.

That story, it turns out, was wildly misinterpreted by the white men who took the Lone Woman to Santa Barbara. When found, she used gestures to tell her tale—emphatic hand movements that, they thought, showed she had stayed on the island because of a lost infant who was later eaten by wild dogs. But when Morris and her colleagues consulted notes by ethnologist John Peabody Harrington, who interviewed some Native Californians about the tale in the late 19th century, they found she had actually stayed on the island with her son, who hid from the newcomers that arrived to take the Nicoleño to mainland California. For years, the pair thrived together on the island. The mother only left San Nicolas after her son’s tragic death in what historians think may have been a shark attack.

Complicated legacies

People of Southern California

Today scholars are still learning more about the vibrant cultures that thrived on California’s Channel Islands for centuries. The Chumash are believed to have lived on mainland California in addition to four of the Channel Islands: Santa Cruz, Santa Rosa, San Miguel, and Anacapa.

Residents of the southern Channel Islands of Santa Barbara, Santa Catalina, and San Clemente have been linked to the Gabrieleño, indigenous peoples recruited by Spanish missionaries to labor at the Mission San Gabriel in the 1700s. Morris and her colleagues note that “In recent years the terms Tongva and Kizh, recorded in mid-nineteenth century and early twentieth century vocabularies, have also been used as names for the Gabrieleño.” These groups may also be culturally linked to the Nicoleños.

The search for more information on the Lone Woman continues. Morris and colleagues have turned their attention to the Nicoleño of Los Angeles, where they’re searching for living descendants of the tribe. It’s a chance, she says, to both honor the Lone Woman and acknowledge Native Californians’ resilience despite repeated colonization and denigration. “They lived on the land for thousands of years. They continue to live today.” Perhaps further research will reveal more about what happened to the Lone Woman’s people long after her death—exploding yet another myth born on that lonely, windswept island.

(Picturesque California conceals a crisis of missing Indigenous women.)