Julius Caesar came. He saw. He conquered. Here's how Rome celebrated.

Julius Caesar received an unprecedented four triumphs, city-wide parties that were the highest honor a military commander could receive.

The morning of September 21, 46 B.C., was a day of celebration for the citizens of Rome. A general was about to claim the highest honor a Roman could receive: a triumph, a spectacular celebration in which he paraded through the streets flaunting his prisoners of war and spoils of victory. This day promised to be like none other before it: Today was the first of four triumphs, all held to honor the same man, Julius Caesar. Over the next two weeks, Rome could look forward to three more giant parades.

Caesar’s triumphs were exceptional not only for their immense expense and grand scale, but also for the fact that he was the only person in Rome’s history to receive four, one for each of his victorious campaigns. By celebrating Caesar, Rome was also celebrating itself, because this general had enlarged and enriched the republic like no other man before him. The one who came closest was Caesar’s ally turned rival, Pompey the Great. He had received three triumphs. Although past triumphs were not the focus of Caesar’s plans, they had set a high bar, which Caesar was set to overcome with great flair. (See also: How Julius Caesar Started a Big War by Crossing a Small Stream.)

Sacred rituals

In the Roman Republic, generals requested triumphs, but it was the Senate that granted them—only if a victory met a series of conditions. The win had to be a major battle (with a minimum of 5,000 enemy casualties ) that ended a war. While the Senate deliberated, the general would wait outside the city gates. If he failed to qualify for a full-blown triumph, he could be granted an ovatio (ovation), a slightly lesser celebration.

When triumphs were granted, a grand procession was held throughout the streets of Rome. Details varied over the centuries, but typically the festivities would last for an entire day. The parade followed a sacred route through the city, starting at the gate, Porta Triumphalis, proceeding to the Campus Martius (Field of Mars) and then along the Via Sacra (Sacred Way) to the temple of Jupiter on Capitoline Hill.

Politicians would proceed first, often followed by musicians and entertainers. Prisoners of war were paraded before Rome, as well as the plunder gained through the victory. For the grand finale, the general and his soldiers (the only time when the army could enter the sacred boundaries of the city) would march as crowds cheered them on.

Walking Ovations

Not all Roman victories resulted in triumphs. If a general won a battle but fell short of the minimum requirements, he could be honored with an ovation, a celebration on a smaller scale. Rather than ride in a chariot, the victor would march. Instead of the toga picta that was solid purple and decorated with gold stars, he would wear the toga praetexta, which was white with a broad purple border. On his head he would wear a wreath of myrtle rather than laurel, and instead of sacrificing oxen he’d have to make do with sheep.

The sense of honor was overwhelming: In a city that viewed monarchs with distrust, the general would be allowed to be “king for a day.” Dressed in royal purple, he would ride in a quadriga, a carriage drawn by four horses. In his hands, he would hold an ivory scepter and a laurel branch. On his head was both a laurel wreath and a golden crown held by a slave, who was also given the task of whispering into the general’s ear reminders of his mortality.

Ending at 19 B.C., the Fasti Triumphales is an incomplete record of those who had been awarded triumphs. Stretching back to Rome’s founders, it shows that Romans believed this accolade to be as old as the city itself. The first triumph in the list is attributed to Romulus, one of the city’s legendary founders. Like many of Rome’s traditions, this connection with its mythical past helped consolidate and sanctify its institutions. The origins of the procession were probably rooted in a religious festival meant to bring about plentiful harvests. As the city grew in size, the triumphs grew in splendor.

Raising the bar

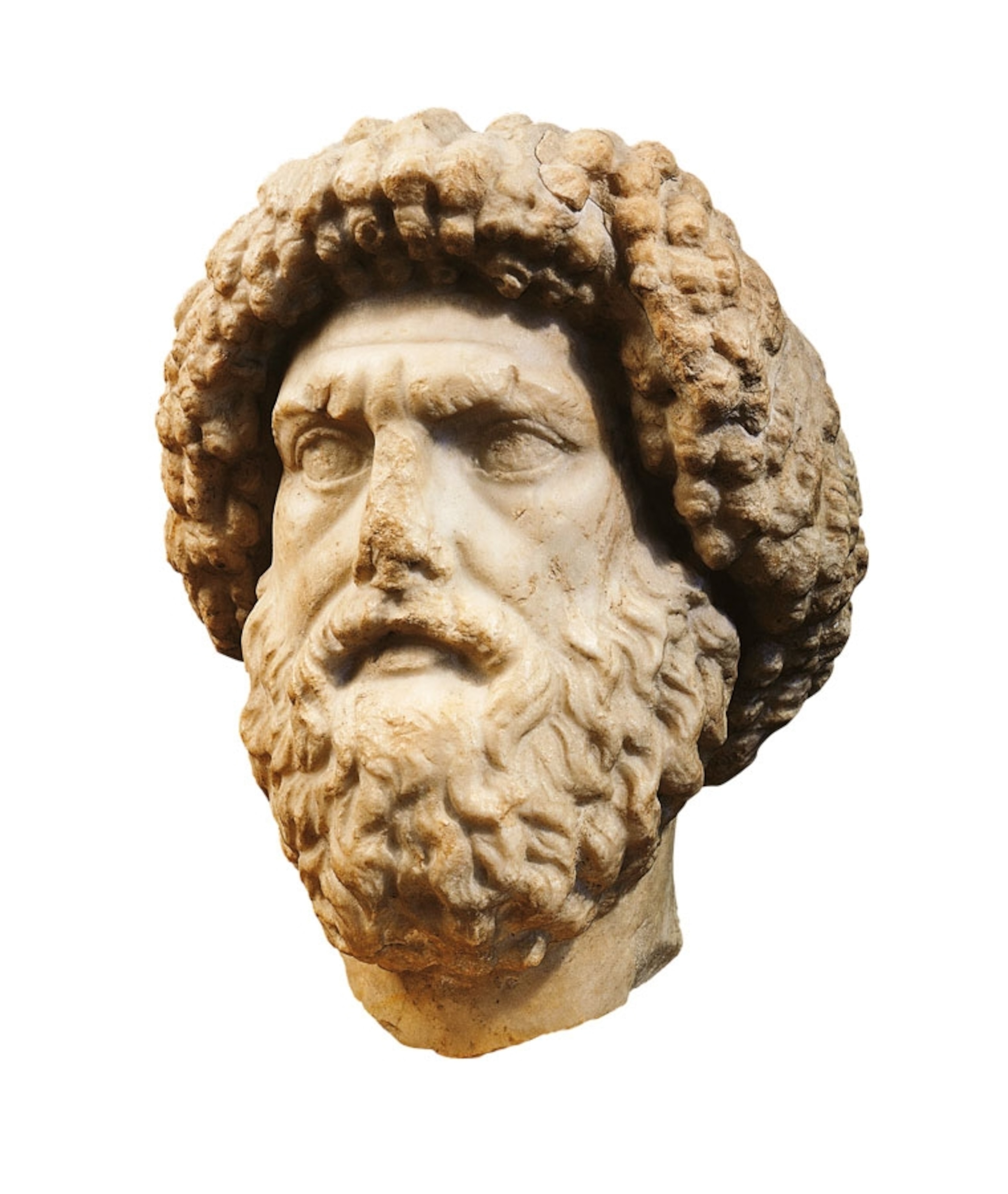

Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus, better known as Pompey the Great, had taken the triumph tradition to new heights, exceeding anything the Romans had experienced before. first-century A.D. historian Plutarch described how the last of his three triumphs, which Pompey celebrated on his 45th birthday in 61 B.C., lasted for two days. Pompey paraded 300 high-ranking hostages through the city, and displayed placards boasting that he had killed or captured 12,183,000 enemies, put out of action 846 warships, and given 1,500 denarii to each of his soldiers, an amount they would normally take a decade to earn.

Writing in the second century A.D., Greek historian Appian detailed Pompey’s expensive tastes, including entering the city on a diamond-studded chariot and wearing a cloak that allegedly belonged to Alexander the Great. Golden-horned bulls were sacrificed, and the people of Rome were gifted parties, banquets, and games.

The number of triumphs was certainly unusual, but Pompey’s victories had unusual qualities. Each of his victories took place on a different continent: He earned his first triumph in Africa (Libya), in 81 B.C.; his second, in Europe, in 71 B.C.; and the third, about 10 years later, in Asia Minor, where he defeated both the eastern pirates and Mithradates VI, king of Pontus and a long-standing menace to the Roman Republic.

Julius Caesar’s career was just beginning when Pompey’s was peaking. In 60 B.C., Caesar had earned enough acclaim and power to form a powerful political alliance, the First Triumvirate, with Pompey and Marcus Licinius Crassus. Although these men were allies, they were also wary of one another, for each one had great power and influence. After Crassus’s death in 53 B.C., the relationship between Pompey and Caesar deteriorated into enmity. Confrontation eventually became unavoidable, and they finally faced each other in a four-year civil war. (See also: Money was not enough for Crassus, the richest man in Rome.)

Caesar was victorious, defeating Pompey’s forces at the Battle of Pharsalus in 48 B.C. Pompey the Great fled to Egypt, where the pharaoh Ptolemy (Cleopatra’s brother) had him murdered, an act which disturbed Caesar, who, despite being an adversary of the general, still saw him as a Roman. The legacy of his former ally turned enemy would trouble Caesar as he turned to his future in Rome.

Tallying up triumphs

Once back in Rome, Caesar’s thoughts turned to triumphs. Before civil war broke out, Caesar had already chalked up some astounding military victories. Between 58 and 50 B.C., his forces waged a series of campaigns in Gaul, conquering new territory for Rome and defeating several Gallic tribes. The climax of the Gallic Wars came in 52 B.C. when the Romans won the Battle of Alesia, defeating a confederation of tribes led by Gallic chief Vercingetorix. This victory was certainly worthy of a triumph.

Caesar’s second great victory occurred in Egypt, shortly after Pompey’s death. Caesar traveled to Egypt, where Cleopatra and her brother Ptolemy and sister Arsinoë were fighting for power. Caesar backed Cleopatra, and she defeated her siblings in 47 B.C. to become sole Egyptian ruler. Caesar’s third victory came later that year. Pharnaces II, king of Pontus, was crushed by Rome at the Battle of Zela in present-day Turkey. (See also: The truth behind Egypt's female pharaohs and their power.)

Victories in Gaul, Egypt, and Pontus qualified Caesar for three triumphs, but he did not hesitate to ask the Senate for a fourth. Caesar scored a victory that led to the downfall of the remnants of Pompey’s forces, the defeat of King Juba I of Numidia in North Africa. During the Roman civil war, Juba supported the remnants of Pompey’s forces with reinforcements during the Battle of Thapsus (in present-day Tunisia) in April 46 B.C.

Juba did die in the conflict, but he wasn’t slain by Caesar’s forces. Sources say that he and Marcus Petreius, a general allied with Pompey, fled and made a mutual suicide pact to avoid capture.

Not only was Thapsus not a victory that would technically justify a triumph, but Caesar’s inclusion of it inflamed tensions in Rome, which was recovering from civil war and the loss of Pompey, whom many still considered a great hero. Nonetheless, Caesar returned to Rome ready to celebrate before the people.

Quadruple triumphs

Over the course of a few weeks in 46 B.C., Caesar staged his four triumphs, beginning with the Gallic. Historians say it started with a curious incident. The first-century A.D. Roman historian Suetonius described how Caesar’s chariot broke as he paraded through city. The general nearly fell, but continued along the route “between two lines of elephants, forty in all, which acted as his torch bearers.”

In the Gallic triumph, Caesar’s men followed behind him. Some carried large placards depicting the most important battles and events. It was customary for them to carouse, singing songs meant to stave off the jealousy of the gods by making fun of the general’s vices. Suetonius recorded a particularly risque verse that poked fun at Caesar’s love affairs:

Home we bring our bald whoremonger; Romans, lock your wives away!

All the bags of gold you lent him

Went his Gallic tarts to pay.

In the Pontic triumph, Suetonius reported how in addition to the placards showing key battle scenes, a wagon was decorated with three simple words: Veni, vidi, vici (I came, I saw, I conquered). Rather than referring to a battle or event, Suetonius believe the phrase referred to the speed with which Caesar’s forces won.

Romans were happy to celebrate victories against foreign powers, but there were mixed feelings about the battles involving Pompey and his allies. Caesar was mindful of this, especially during the fourth triumph. According to Appian, Caesar “took care not to inscribe any Roman names in his triumph (as it would have been unseemly in his eyes and base and inauspicious in those of the Roman people to triumph over fellow-citizens).” He was astute enough to avoid any mention of Pompey. The former leader remained much loved and Caesar had to watch his step. Even so, Caesar did allow this campaign to be represented in posters.

Parading captured foreign enemies before the populace was enthusiastically welcomed. Traditionally, they would be presented in chains or cages before the crowds and then executed. It had been six years since Vercingetorix’s defeat, and the Gallic commander had been in prison ever since. As part of his triumph, Caesar paraded the vanquished leader through the streets of Rome and then had him executed on Capitoline Hill.

To the Victors

The utmost military glory was the spolia opima, the weapons stripped from the body of an enemy chieftain killed in one-on-one combat. Roman history records only three instances of this happening. Tradition holds that Romulus, Rome’s co-founder, challenged and killed Acron, the king of the Ceninenses, in single combat. He is said to have hung Acron’s weapons in an oak tree. In the fifth century B.C., general Aulus Cornelius Cossus defeated Lars Tolumnius, king of Veii, at the Battle of the Amio. Evidence for the first two incidents is hazy, but historians do believe that in 222 B.C., Marcus Claudius Marcellus killed the Gallic king Viridomarus to claim the spoils of war.

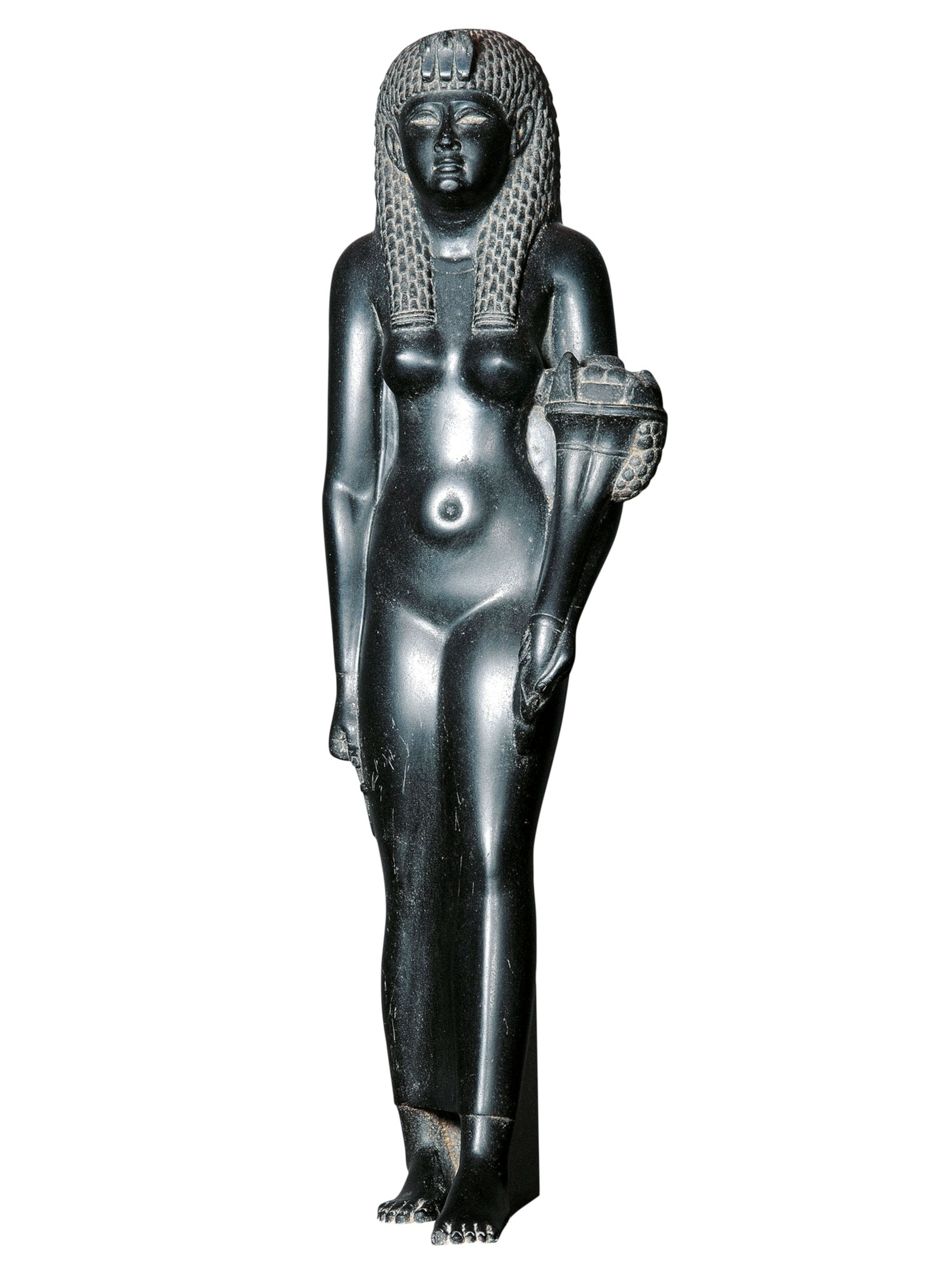

Not all of Caesar’s defeated enemies met such a fate. During the Egyptian triumph, Cleopatra’s sister Arsinoë was bound in chains. Her demeanor aroused the crowd’s sympathy. Sensitive to the feelings of the people, Caesar had her exiled to Ephesus rather than killed.

Bread and circuses

In addition to the processions, Caesar spared no expense for grand entertainments for the Roman people. Appian described the action:

[Caesar] put on various shows. There was horse-racing, and musical contests, and combats—one with a thousand foot soldiers opposing another thousand, another with 200 cavalry on each side, and another that was a mixed infantry and cavalry combat, as well as an elephant fight with twenty beasts a side and a naval battle with 4,000 oarsmen plus a thousand marines on each side to fight.

Caesar generously rewarded his troops with 20,000 sesterces—far beyond what they would have earned in a lifetime. He also gave a magnanimous sum of 400 sesterces to every citizen, distributed food, and staged gladiatorial combats and athletic events.

The triumphs were long remembered for their pomp and splendor, but some historians believe they stirred up opposition to the conquering hero. To some, the grandstanding was at odds with Rome’s republican values of simplicity, discipline, dignity, and virtue. Caesar had spent extravagant sums on self-promotion, causing several Roman senators—such as Cassius, and Brutus—to grow wary of him, wondering what his true motivations might be.

Grumbling about Caesar’s ambitions was only fueled by this ostentation. Opposition to his power increased among this faction of senators, who hatched a successful assassination plot in the 18 months following the four triumphs of Caesar.