Napoleon lost the Battle of Waterloo—here’s what went wrong

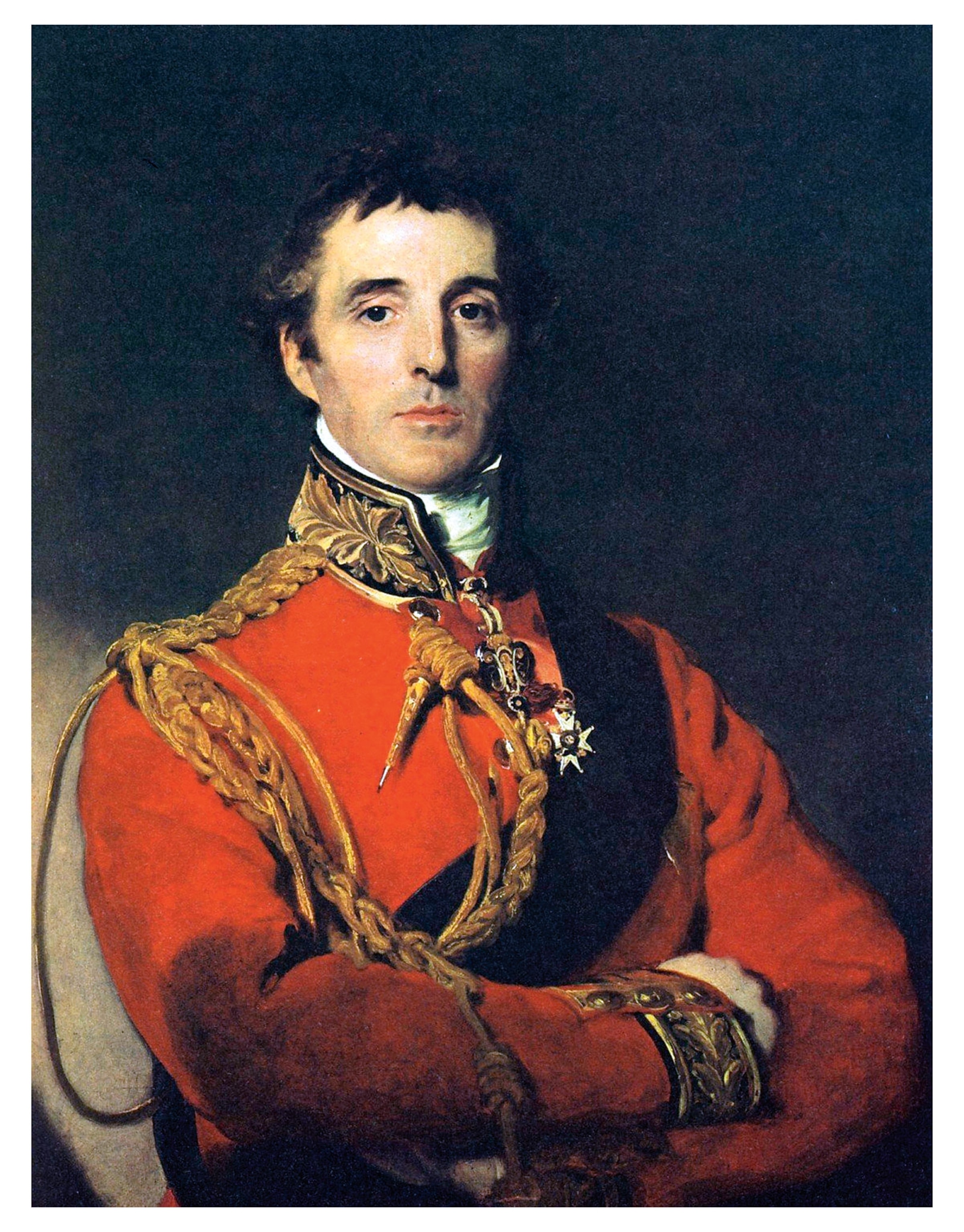

Napoleon made a bold return from exile in 1815 only to lose his last shot at empire in a crushing defeat delivered by the Duke of Wellington and the combined forces of Europe.

In the early 1800s Napoleon Bonaparte stormed across Europe, swallowing up territory for his French Empire and challenging the supremacy of Britain on the seas. From 1804 to 1814, the Napoleonic Wars raged, as Britain, Prussia, Austria, and Russia all fought to hold back the fiery emperor of France. In 1814 it looked as though they had succeeded. Napoleon had abdicated and was exiled to the island of Elba. In France the Bourbon king Louis XVIII had been restored to power.

Then, in late February 1815, Europe received a shock: The audacious Napoleon had left Elba and set sail for France. It is hard to overestimate the dismay and fear provoked by this news. Napoleon’s banishment the year before had been achieved after years of momentous and costly battles on land and at sea. His escape, many feared, would restart French imperial expansion, and once more plunge Europe into war.

(See also: How the Battle of Waterloo changed the world.)

In spring 1815 British, Prussian, Austrian, and Russian forces rushed to regroup as Napoleon started mobilizing his army. The countdown had begun to a last epic showdown. This time, Napoleon faced a coalition of nations led by one of his most skilled British adversaries, the Duke of Wellington. Despite being on opposite sides, both men had shaped, and been shaped by, the extraordinary events that had transformed Europe in the late 18th century.

The First Rise and Fall

Born on the island of Corsica in 1769, Napoleon Bonaparte possessed furious intelligence and relentless ambition. As a young soldier, he supported the radical ideals of the French Revolution and rose rapidly through the ranks of the French army. Proposing an aggressive approach by attacking Britain’s territories en route to India, Napoleon led the invasion of Egypt in 1798. By 1799 France was at war with most of Europe. Returning to France, Napoleon took part in a coup against the government and then became first consul in February 1800. His forces defeated Austria, and in 1804 Napoleon crowned himself emperor of France.

(Why claiming the crown cost Napoleon a famous fan: Beethoven.)

The French Empire’s renewed hopes to break British naval power were dashed at the Battle of Trafalgar in 1805. But even as Napoleon abandoned hope of invading Britain, his Grand Army went on to occupy swaths of Europe in what is now Germany and Poland. To the west, he enforced a trade blockade on Britain by invading Portugal, its commercial ally, and brought much of Spain under his control in the process.

It was on the Iberian Peninsula that the future Duke of Wellington, born Arthur Wellesley, first defeated Napoleon. The Irish-born commander had chalked up military successes in India before being sent to Portugal in 1809 where he helped guerrillas resist Napoleon’s occupation. Despite initial setbacks, Wellesley managed with patience and skill to expel Napoleon from Portugal in 1811 and won decisive victories against the French in Spain in 1813, dealing a major blow to the emperor’s plans for European domination.

The French Empire was weakening. Following the French Grand Army’s ruinous attempt to invade Russia, allied forces invaded France from all sides. In April 1814 Napoleon was forced to abdicate and accepted banishment to Elba, a few miles off the Italian coast, where he was not exactly a prisoner. He was granted sovereignty of the island, as well as an armed guard. A flow of intelligence from the mainland helped him plan for his daring return to the continent in early 1815.

The Comeback Trail

On March 20, Napoleon reached Paris with the support of the masses ringing in his ears. Despite his claims to want peace, Britain, Austria, Prussia, and Russia were wary. Together, they signed what amounted to a declaration of war.

Events moved swiftly, and the restored French emperor had little time to organize. With enemy armies massing on France’s northern frontiers, he attempted, unsuccessfully, to put together a volunteer force to supplement the standing army at his disposal. But even in this diminished state, the French army was a fearful opponent. Its troops were experienced fighters, and its commander still inspired passionate loyalty.

(Here's how Napoleon fed his army.)

The allied forces consisted of British, German, Belgian, Dutch, and Prussian troops, who were divided up into various detachments on the border between France and present-day Germany. The British commander, the Duke of Wellington, patiently decided to wait for the enemy to attack rather than force their hand.

Napoleon himself, brimming with confidence, was planning for a decisive victory. Ignoring advice to postpone engagement, he left Paris on June 12, 1815, to join up with his army in Belgium—where Wellington’s troops and Gebhard von Blücher’s Prussian army also lay in wait. On June 14, he signed a proclamation: “The honor and happiness of our country are at stake and, in short, Frenchmen, the moment has arrived when we must conquer or die!”

A double battle took place on June 16 in Quatre-Bras and Ligny; both were French victories, although neither was a fatal blow to Napoleon’s enemies. On June 17, heavy rains soaked the ground and the French soldiers. The wet fields and muddy roads became a swampy mess.

A Military Quagmire

As dawn broke on June 18, Wellington and Napoleon organized their forces. Wellington set up his headquarters in Mont-Saint-Jean on the road from Brussels, not far from the town of Waterloo. He had deployed the bulk of his 68,000 troops along a two-and-a-half-mile-long ridge. Three farms—Papelotte, La Haye Sainte, and Hougoumont—stood along it. The British commander stuck to his defensive tactic, knowing he needed to wait for Blücher’s detachments— some 50,000 men in total—to arrive. After the clash at Ligny, Blücher had withdrawn to Wavre, a few miles from Waterloo.

Napoleon’s camp was in the village of Maison du Roi. Because French forces totaled roughly 72,000 men, Napoleon hoped to take advantage of the separation of the Prussians from the British and destroy Wellington’s forces as soon as possible. The emperor was convinced that victory was within his grasp and that it would be quick and easy. “I tell you Wellington is a bad general,” he said: “[T]he English are bad troops, and this affair is nothing more than eating breakfast.” But the emperor’s plan was thwarted by the muddy conditions and morning fog, which prevented an early start. The conditions forced him to delay his attack until late morning. Some historians believe that had it not rained, Napoleon would have defeated the allied army within a few hours, long before the Prussians arrived.

In the end, the battle began sometime after eleven in the morning. Always on the offensive, the French focused their forces on two key points on the front: The two farms that the allies had fortified, Hougoumont and La Haye Sainte. The battle to take these sites stretched on through the day, causing great losses among the French, who were able to launch successive attacks on the allies’ infantry. Cavalry charges struck terror into the forward allied marksmen, while superior French artillery pounded the Anglo-Dutch formations throughout the day. Disciplined French infantry attacks punched more and more gaps in the allied lines, so that by the afternoon some of Wellington’s officers, running out of munitions, feared the battle was lost.

None of the French attacks, however, achieved the aim of breaching the front. The allied infantry, in particular the British, showed determined resilience in facing the French onslaught. Some formations suffered unprecedented losses, such as the Inniskilling Regiment, which lost two-thirds of its men in 45 minutes.

Finally Facing His Waterloo

Even so, the strain was becoming intolerable. Wellington desperately awaited news of Blücher’s arrival: “Night, or the Prussians, will save us,” he said. It was at around 4 p.m. that Blücher’s forces started to attack the French flank at the hamlets of Plancenoit and Papelotte. But the danger for Wellington was not over yet. The La Haye Sainte farmhouse fell to the French at around 6 p.m.

An hour later, the allied forces faced the terrifying charge from the Imperial Guard, the force Napoleon always reserved to decide battles. They, the emperor thought, would break the allies. But he had miscalculated. He had already sent several regiments of his Imperial Guard to fight the Prussians. They were sorely missed by their comrades during the final push. As they charged, allied gunfire ripped them apart. Stunned, the Imperial Guard faltered.

The French troops scattered in retreat. In his memoirs, Capt. Jean-Roch Coignet recalled: “Nothing could calm [the soldiers]; terror had taken control of them.” At 8:15 p.m. Napoleon ordered a retreat. He realized a mortal blow had been struck and returned to Paris, where he abdicated in favor of his son on June 22.

The victory at Waterloo came at a heavy cost: Estimates vary, but historians place Wellington’s casualties around 15,000 and Blücher’s at about 8,000. Napoleon suffered roughly 25,000 casualties and 9,000 Frenchmen were captured. Wellington was overwhelmed by the loss of life: “I hope to God that I have fought my last battle.” A month after the battle, Napoleon gave himself up to the British, who banished him to St. Helena, an island in the middle of the Atlantic. The Napoleonic Era was over for good.