Jane Goodall championed animal conservation for six decades

The National Geographic Explorer dedicated her life not just to chimpanzees, but global conservation.

Dr. Jane Goodall DBE, UN Messenger of Peace and founder of the Jane Goodall Institute was certainly a rarity among conservationists: She was a household name. For more than six decades, she was the world’s preeminent ethologist and champion for animal conservation.

But Goodall's path to success was atypical. She was born in London, England in 1934, attended secretarial school and later worked as a waitress to fund a one-way plane ticket to visit a family farm in Kenya. There, she arranged to meet the famed palaeontologist Louis Leakey. In 1960, the year she began her now-famous study of chimpanzees in Gombe Stream National Park, primatology was an almost entirely male-dominated field. Moreover, Goodall had no university degree and no formal training as a scientist or primatologist. Instead, she had an abiding love of animals that had driven her, several years prior, to cold call Leakey.

Leakey, a paleoanthropologist who with his wife Mary was famed for uncovering evidence that the earliest humans lived in and migrated out of Africa, hired Goodall as a secretary in 1957. A few years later, after receiving a grant from the National Geographic Society, Goodall embarked on a mission to Gombe in Tanzania, where her work would remake our understanding of primates.

Goodall was 26 years old when she first arrived in Gombe in 1960. She brought her mother, Vanne Goodall, as her chaperone after national park officials insisted she shouldn’t be alone. In the first few weeks they contracted malaria, and interacting with the chimps was challenging — they’d disappear when Goodall tried to approach, or simply go unseen for miles. She described life in her letters to Leakey as “depressing, wet [and] chimpless.” Eventually, she established trust and made prolific observations over the subsequent several months.

One observation in particular shook the foundations of primatological and anthropological thought. While observing a chimpanzee, Goodall noticed him using pieces of grass to “fish” for termites while feeding. She named the high-ranking male David Greybeard.

.jpg)

Up to this point, the scientific consensus was that tool-making separated humans from their primate cousins. Goodall’s observation upended that. Leakey himself wrote in response that “We must now redefine man, redefine tool, or accept chimpanzees as human.” She continued to befriend other chimps and their future generations, naming those she grew close to, like Fifi and Flo.

By the end of 1960, her observation and recording of behavior patterns that challenged early beliefs regarding chimpanzees inspired Leakey to advocate for further financial support on Goodall’s behalf. In 1961, due to Leakey’s persuasion, she was awarded her first grant from the Society to continue her work.

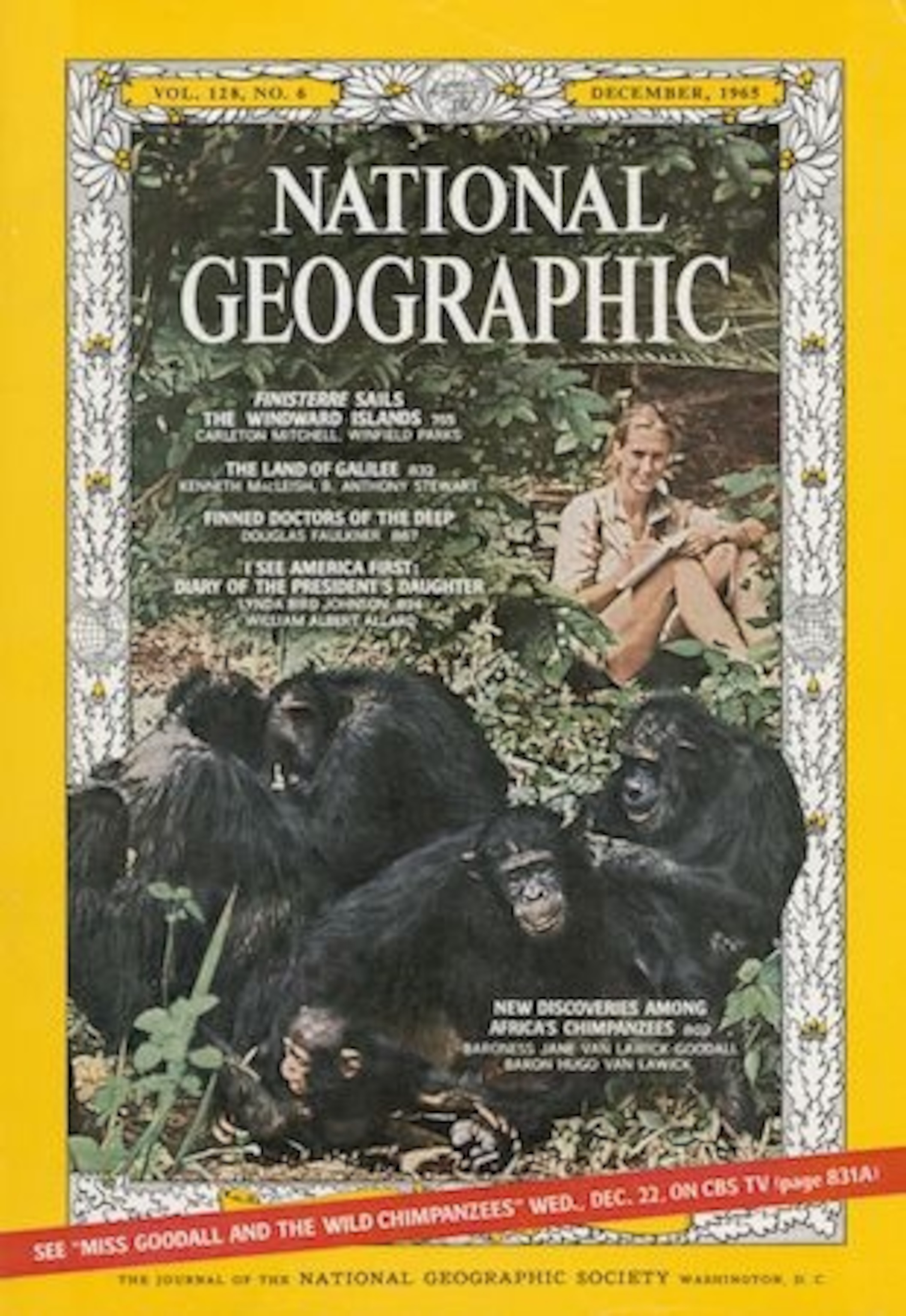

Her first National Geographic magazine feature, “My Life Among Wild Chimpanzees,” was part of the August 1963 issue and appeared on the cover.

She continued to pen articles and made her Society television documentary debut in 1965 — the same year she was recognized with the Society’s highest honor, the Hubbard Medal. She published a National Geographic book the following year, and dozens of Society grants supported her work over the decades.

Goodall’s work in Gombe has never stopped. In fact, the Gombe Stream Research Center (GSRC), now run mostly by Tanzanians, is one of the longest field studies of an animal species in history.

She later became engaged in a complementary effort: animal conservation. The Jane Goodall Institute, started in 1977, has worked for decades to secure the habitats of chimpanzees and other species. Her Roots & Shoots youth-led global environmental and humanitarian program, which Goodall started in 1991, is still her Institute’s program for fostering young conservation leaders across more than 60 countries.

After attending a 1986 primatology conference, Goodall directed her focus toward activism. “I realized I had to stop living selfishly in my own little paradise and use the knowledge I’d gained to do what I could to help,” she said. She began speaking out about the threats facing endangered species, environmental crises and inspiring action, traveling up to 300 days per year to raise awareness.

In 2002, she was appointed a UN Messenger of Peace, and in May 2021, Goodall was named the recipient of the prestigious lifetime achievement award, the Templeton Prize, which honors rare individuals who have responded to the deep challenges of our times with inspiring humility and curiosity. In January of 2025, she received the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the United States’ highest civilian honor.

Goodall died on Oct. 1, 2025 in Los Angeles, California. She was 91.

“I'd like to be remembered as someone who really helped people to have a little humility and realize that we are part of the animal kingdom,” she once said, “not separated from it.”