Anya Brown is investigating microbes’ critical role in coral reefs

Her research team’s contributions could hold promise for coral adaptation and conservation.

“So the clue was, ‘This temperate coral undergoes quiescence in the winter. Another word for this is … ?’” Anya Brown has spent most of her adult life around coral reef systems. Her brother, meanwhile, has cultivated a career as a writer on the American quiz show, “Jeopardy!”

He once consulted her for a marine science question idea, which aired on season 39 (episode 8924) of the series. “The word was ‘hibernation,’” Brown reveals, and it had formed the basis of her post-doctoral research assessing how corals go dormant, and what happens to their microbial communities when they do. She’s devoted her career to investigating how microbes influence ecology and the evolution of macroscopic species.

“So, I go from the teeny tiny, to the large,” says Brown, a marine biologist, ecologist, National Geographic Explorer and assistant professor at the University of California, Davis.

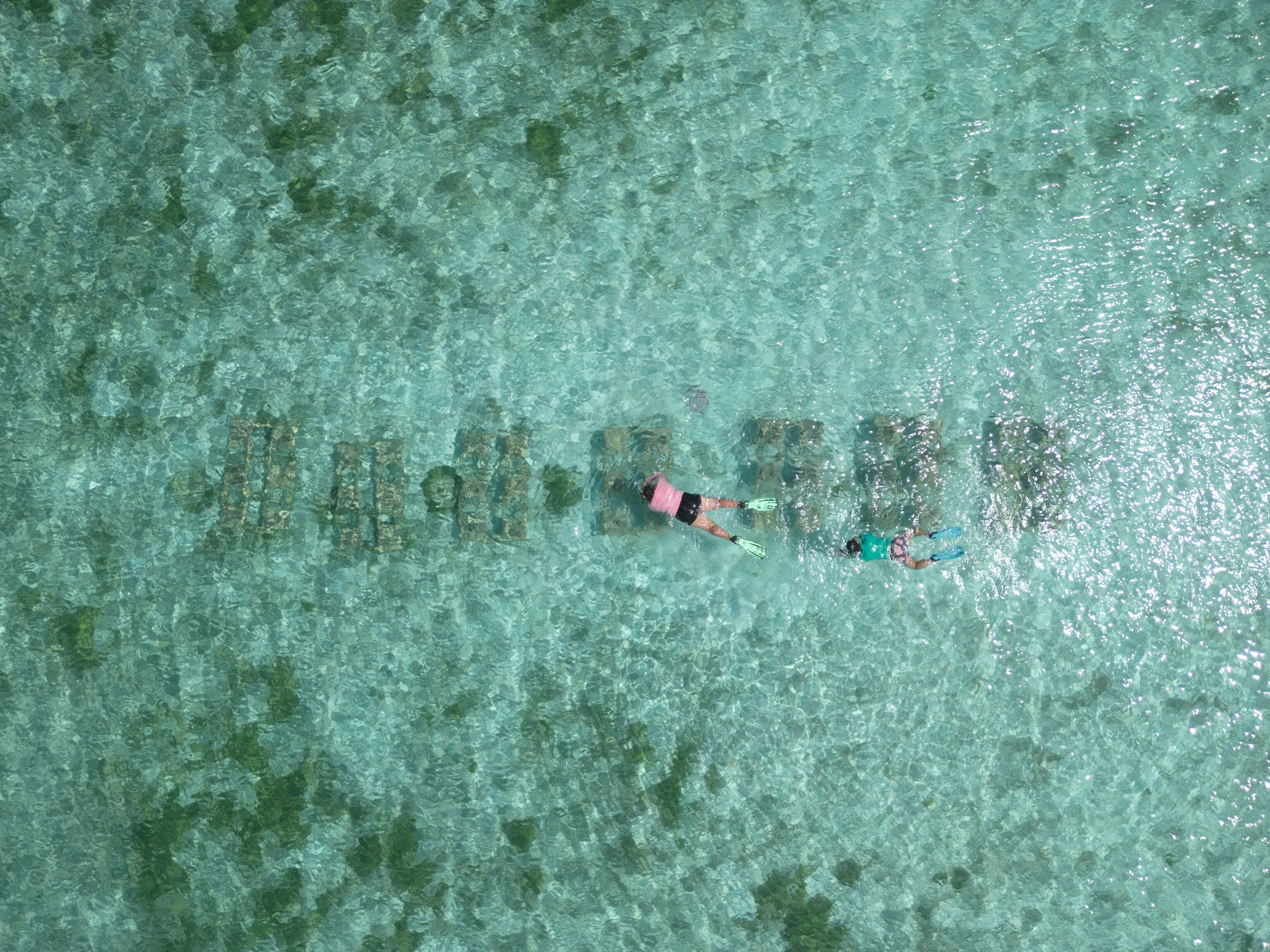

Since 2024, Brown has been a lead scientist on the National Geographic and Rolex Perpetual Planet Ocean Expedition in Rarotonga, the most populous of the Cook Islands. In close collaboration with the Rarotonga nonprofit organization Kōrero O Te 'Ōrau, local partners Teina Rongo, Jackie Rongo and Siana Whatarau, and fellow UC Davis professor Dr. Rachael Bay, Brown has planted and monitored a coral nursery to better understand the nuances of coral bleaching — the loss of the coral’s nutrient supply via two important types of microbes: symbiotic bacteria and algae (also called zooxanthellae), which live in coral tissues. The team is examining the role of microbes and coral genetics in heat tolerance and bleaching resistance.

“It turns out some coral species are far more resistant to bleaching, meaning they don’t respond to the heat stress, than others,” explains Brown.

The team’s findings could hold promising implications for the recovery of dwindling marine life as rising ocean temperatures have caused more frequent, longer-lasting bleaching events in recent years.

Moreover, “It’s possible that some species that don’t bleach under heat stress, are rescuing coral types that do.” This would be consistent with Brown’s research in Little Cayman, Cayman Islands, which found that nursery corals organized with different genotypes decreased disease.

But to say with more certainty whether this is the case in Rarotonga, the team needs to start by examining coral DNA.

Reefs supporting communities

“You can think of reefs as the rainforest of the sea,” explains Brown. They support a quarter of all marine life.

“Some species rely on them for short periods before moving out to the open ocean, others, like some fish, spend their entire lives in and around reefs.”

In Rarotonga, reefs provide vital protection — they act as shields against storms by buffering the islands from heavy waves that might otherwise cause coastal erosion. The reef ecosystems sustain a variety of marine species, including fish fundamental to local fisheries and livelihoods. Healthy reefs attract tourism and boost the local economy, Brown says.

Rarotongan reefs have recently faced bleaching events and outbreaks of the carnivorous crown-of-thorns starfish, leading to a decline in live coral cover. Understanding the resistance and ability of corals to recover is essential for effective restoration and conservation efforts in the Cook Islands.

From the field to the lab

Back at her home base at the UC Davis Bodega Marine Laboratory (BML), Brown and a team of research assistants, graduate students Deva Holliman and Kenzie Pollard and junior specialist Callie Hundley, work with coral samples from the island nursery. Graduate student Katie Erickson also assisted in the project from the field in Rarotonga.

“In my day-to-day I take a lot of little vials out of a freezer and transfer liquid from one place to another,” Brown chuckles. She retrieves a frozen piece of coral from a negative-112-degree-Fahrenheit (negative-80-degree-Celsius) freezer. It thaws and she explains how this “little pool of liquid has all the information we need.”

For now the Rarotonga coral study is focused on three key variables during coral bleaching events: bacteria and algae (led by Brown) and coral genetics (led by Rachael Bay).

Brown’s routine of fluid transfers is part of DNA extraction. The liquified genetic material holds clues about how vital coral ecosystems survive the accelerating impacts of climate change.

Corals have a very narrow range of temperatures they are able to survive in. Only 1-2 degrees Celsius warmer than normal is enough to stress corals. Since 1950 half of the world’s coral reefs have disappeared.

During heat stress, corals expel their algal symbionts and shuffle their bacterial symbionts. The algal microbes are responsible for their nutrient supply, and thus, their color, hence the pale — or bleached — result when the coral pushes them out. Brown hypothesizes the resilient coral may be doing a better job of hanging onto key microbes that help them endure, and then sharing these microbes and chemicals that result in rescuing their less-resistant neighbors.

“I think what’s going to be cool about our study is we’re going to start to see, well, what’s different between the more resistant corals versus the more sensitive to bleaching corals,” Brown says. “Is there a precursor or some signal after a heating event? Are there different levels of stability between corals that are more or less tolerant?”

When Brown and the team set up the experiment in Rarotonga, the idea was to test for warning signs ahead of bleaching. “Some studies suggest that you see changes in the bacteria before you see changes in the algae,” she says. “So we set up the coral nursery. Then we were hit with a marine heat wave.” Their setup in 2024 coincided with the world’s fourth global bleaching event. The Cook Islands saw record heat.

“We saw that we had captured differential bleaching during a natural event. So then we knew some genotypes did bleach and some genotypes did not,” recalls Brown.

With this understanding, the team arranged groups of corals with mixed genotypes — some with high heat tolerance and some with lower tolerance — and others consisting of only single genotypes. With all groups exposed to equal high temperatures, the researchers will observe whether diversity within the group improves resistance to bleaching.

Right now, the team is in the phase of optimizing the DNA samples so they can examine which microbes are present in healthy, unbleached corals versus bleached corals to help identify key players in heat stress tolerance. In six months to a year, Brown estimates, they’ll be able to draw further conclusions about microbial roles in heat stress tolerance.

The ‘ideal system’ to study

Growing up in the northeastern United States, nowhere near tropical corals, Brown got hooked on them during a high school field trip. “It opened my eyes to a whole new world. I’ve been training to be a scientist in some shape or form since then,” she says.

Brown wasn’t raised by scientists. She comes from a line of relatives devoted to social service: Her mother was heavily involved with education for women and girls, her grandmother was a teacher, her great-grandmother was a social worker. Brown’s father has spearheaded countless non-profit projects.

“My parents and I do very different things during the day,” Brown chuckles.

A poster that reads “flora of the sea” above colorful illustrations of starfish and coral varieties hangs on one of the walls of Brown’s sunny office. A gift from her mother.

“I laughed so hard because those are all animals, so it should say fauna. But it is very sweet and I love it.”

When it was time to choose a master’s degree program, she began investigating the relationship between corals and seaweeds. “Over time, it’s been this coral thing,” Brown says. “Coral became this ideal system to understand the relationships organisms have with this rich, invisible community like in our guts, or seagrass with their pathogens and beneficial microbes,” she adds. “It’s the kind of thing that unites so much of life on Earth.”

She saw disease run through the coral nursery she worked with during her post-doctoral research. “This system that I’m devoting my life to studying, it can be gone in a blink.”

It got her wondering about their microbiomes, how they work, and what their future looks like in the face of rapidly changing environments.

Over the years, Brown has led research on reefs in French Polynesia, the Virgin Islands and Puerto Rico in addition to her studies in the Cayman Islands and Rarotonga.

A coastal research center

Though there are no living coral near the Bodega Marine Lab, the facility, located on Bodega Marine Reserve protected lands, is a hub for ecological research.

As one of eight UC Davis faculty based at the lab, Brown teaches a microbial ecology class. At a given time around 100 researchers, staff and students whip around the building discussing the problems they’re trying to solve: the best way to repopulate the critically endangered white abalone, how to get sea urchin population explosions under control, and what will help revive the resulting barren kelp forests. Brown is in her element.

Built in the 1960s, the BML’s library houses an extensive archive of past student research papers, some dating back nearly a century. The space is shared with the White Abalone Recovery Project, the Shellfish Health Lab and the Kashia Band of Pomo Indians.

Experiments are running at every turn on the property: Three towering metal toothpicks form fog collectors that measure moisture and toxins in the air, while high-frequency radars send silent signals to ocean waves that help map currents that track things like the movement of larvae, or provide crucial emergency information like the paths of oil spills and tsunamis.

There are harbor seals, curious as puppies and guarded like babies. Picnic tables are the researchers’ wildlife watching point, steps from an overlook that dangles just above a quiet beach. Lucky researchers and visitors spot whales, badgers and sea stars.

Climate change’s impacts are palpable here too. Starfish populations have plummeted from disease outbreaks, kelp forests have disappeared in many areas, and aggressive hunting nearly decimated otter and abalone populations. Yet the lab and its scientific community offer a sliver of hope: The BML captive breeding program of white abalone is one example of extreme success.

“The white abalone was one of the last abalone that was fished because it’s in deeper water,” explains Ellie Fairbairn, a trained toxicologist who directs the lab’s education and outreach programs. Eventually, humans took 99 to 99.9% of white abalone from the ocean between 1970 and 1980.

“The good news, and the bad news, is that there are more white abalone in this lab than there are in the ocean,” says Fairbairn. BML scientists are experimenting with kelp restoration as well. “Some of the things we’re doing with corals, they’re doing with kelps,” explains Brown. “There’s so many parallels across all of these different ecosystems, particularly in terms of warming effects.”

Though thousands of miles from Rarotonga, Brown conducts similar thermal resistance experiments on local eelgrass. She’s been growing pathogenic microbes at different temperatures to observe how heat affects their proliferation, and the vulnerability of the plant.

“Eelgrass is like coral in that it’s a colonial, foundation species. The rest of the ecosystem relies on them,” explains Brown.

Assessing coral genes, and more

Brown will return to Rarotonga next in the summer, building on support and resources provided by the National Geographic Society, to assess the genetic factors that may contribute to building more resilient coral. This phase is led by Dr. Rachael Bay and funded by the National Science Foundation (NSF).

In addition, the team will plant more coral varieties to the existing nursery and host a workshop on using the Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) lab technique, the process Brown employs at the BML, to identify algal symbionts of coral.

“I think and hope that our insights will provide a new angle and perspective to understand the reefs,” says Brown. She has high hopes for the future of coral restoration around the island, which wasn’t very active before she and local teams assembled for their research. “There had been active gardening work [previously], but in the period of time we were there in 2022, there was no active coral restoration,” she recalls. “It’s amazing because in a year that changed [to include several groups].”

Looking ahead, Brown says “I think a good next step for this study is how these multiple heat wave events influence corals and what happens long term. Are they more or less likely to reproduce, even if they do survive? Are they growing more or less with each event?”

The absence of visible bleaching in coral does not necessarily indicate it is not experiencing stress. This is something Brown is keen to investigate further.

The good news from the Rarotonga experiment so far is some coral that bleached, recovered. Brown says when water temperatures began to cool, corals regained their symbionts and came back to life with vibrant color.

“We might have more resilient corals than not resilient corals in this ecosystem.”

ABOUT THE WRITER

For the National Geographic Society: Natalie Hutchison is a Digital Content Producer for the Society. She believes authentic storytelling wields power to connect people over the shared human experience. In her free time she turns to her paintbrush to create visual snapshots she hopes will inspire hope and empathy.