Voyage to the Deep

For years he dreamed of diving to the bottom of the Mariana Trench, the deepest spot in the ocean. But to make it happen, explorer and filmmaker James Cameron had to design and build his own vehicle, a futuristic submersible called DEEPSEA CHALLENGER. After seven years spent on research, design, and testing, one question remained: Could the sub survive the crushing pressure at 36,000 feet? As he neared the end of a two-month expedition, Cameron was staking his life on the answer.

The village chief, a wispy fellow with an easy smile and snowy muttonchops, came aboard James Cameron’s expedition ship in Papua New Guinea with an entourage. The five young men who attended him called him Big Man, a term of respect. The Big Man spoke in a local dialect, but his meaning came across. Who are you, he asked Cameron, and what are you doing here?

Cameron smiled. “C’mon,” he said. “I’ll show you.”

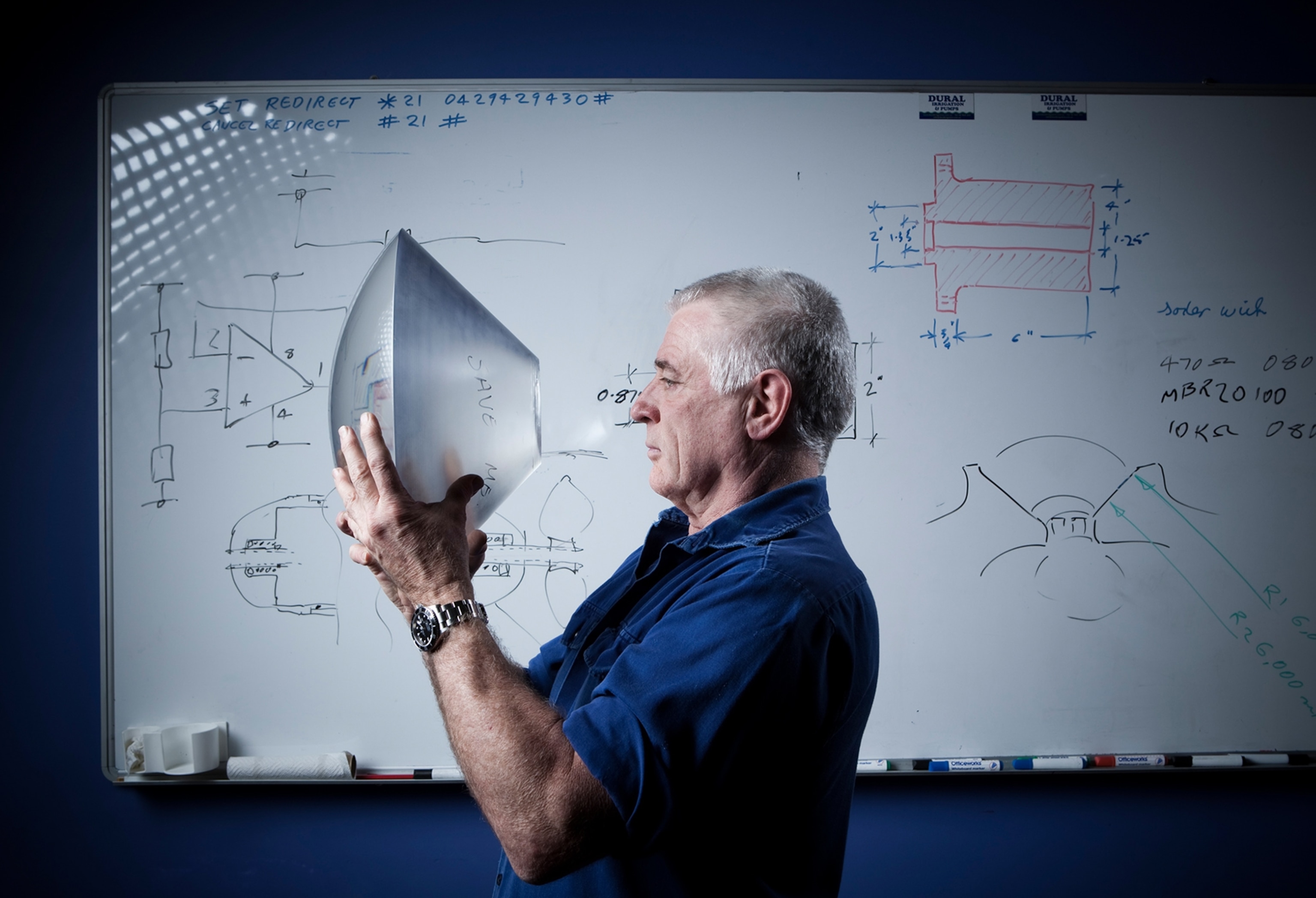

He led the Big Man and his entourage to where DEEPSEA CHALLENGER, a sleek, 24-foot submersible, rested in its cradle. In a few days Cameron planned to deploy the craft in a deep seafloor trench off the coast, a shakedown run for the big dive to come in the Mariana Trench. The chief ’s eyes widened. His men ran their hands over the vehicle’s brilliant green composite skin. With its blinking battery array and robotic limbs, the machine could have been mistaken for a spaceship.

“This,” said Cameron, “is my sub.”

Big Man peered through the polished-steel hatch.

“I sit inside there,” Cameron said, gesturing toward the sub’s pilot capsule, a sphere of two-and-a-half-inch-thick steel designed for a single pilot. “We close the hatch. And then go pshewww all the way to the bottom. Straight down.”

Cameron was a master at distilling a story into its simplest form. (He once famously pitched his best-known film in six words: “Romeo and Juliet on the Titanic.”) So it came as no surprise to hear him describe the first solo dive to explore the deepest spot in the ocean in such radically abridged form. Nothing to it: Close the hatch, and down we go.

But in truth it was not so simple.

Rewind to three weeks earlier. DEEPSEA CHALLENGER lay in its cradle on the deck of its mother ship, Mermaid Sapphire, in Jervis Bay, Australia, a quiet anchorage 125 miles south of Sydney. Cameron’s plan was to hopscotch across the South Pacific, testing DEEPSEA CHALLENGER in a series of ever deeper dives before subjecting it to the crushing pressure of the Mariana Trench’s 16,000 pounds per square inch. The team had plotted a course that would take it from shallow Australian coves to a deep trench off the coast of Papua New Guinea and then to the open seas above the deepest part of the Mariana Trench, known as the Challenger Deep. No manned craft had visited the location since the U.S. Navy bathyscaph Trieste reached a depth of 35,800 feet in 1960, piloted by Lt. Don Walsh and Jacques Piccard. Cameron had invited Walsh on board the Mermaid Sapphire to contribute his firsthand knowledge of the trench.

Before steaming off to Papua New Guinea, though, the crew had scheduled a dive to conduct some engineering tests and to give Ron Allum, the sub’s co-designer, some pilot training. The dive would also provide an opportunity to shoot some aerial footage of the sub being launched. Andrew Wight, an Australian director and Cameron’s longtime documentary partner, was producing a film about the expedition, along with cinematographer Mike deGruy. Wight, an experienced pilot, had his personal Robinson R-44 helicopter parked at a nearby airfield. The weather was perfect for it: open skies, a gentle breeze.

Both men were close friends of Cameron’s, and he was committed to helping them document every aspect of the expedition. He and his engineers had designed tiny high-definition cameras, encased in titanium to withstand the pressure and capable of recording in 3-D or taking close-up images of organisms discovered in the depths. But it was the engineering accomplishment of the dive itself that mattered most, and the knowledge that could be gained from it. Cameron had also brought aboard a small team to operate two scientific landers, unmanned vehicles the size of large refrigerators that sampled the sediment, seawater, and biology at the bottom. They would dive in concert with the sub.

Compared with other submersibles, DEEPSEA CHALLENGER was an aquatic rocket ship. Deep-diving craft tended to be fat, blocky, and slow, wasting too much of their dive time getting to and from the bottom. Cameron intended to get to the bottom fast and come up even faster, allowing for more time to explore the seafloor. His harmonica-shaped craft had a special polyester-epoxy fiber skin, which was wrapped around a core beam of buoyant syntactic foam. (“Foam” is misleading. Formed by suspending hollow glass microspheres in an epoxy resin, syntactic foam performs more like wood than like Styrofoam: It is hard, strong, dense, and buoyant.) The pilot’s sphere was socketed into the bottom of the sub like the head of a ballpoint pen. Six small thrusters propelled the vehicle across the bottom, and another six provided some control over its vertical position in the water column. But the main propellant in the descent and ascent was caveman simple. Anywhere from 600 pounds to more than 1,000 pounds of steel weights pulled DEEPSEA CHALLENGERdown, depending on the dive depth. Drop the weights, and the sub sped skyward. “The trick is to make sure those weights come off,” said Cameron. “We’ve designed about eight different ways to make sure they do.”

Ron Allum squeezed into the pilot’s sphere for the test dive. The summer sun beat down on Mermaid Sapphire’s deck. Team member John Garvin ran an air-conditioning hose into the sub’s cockpit to keep it cool for Allum. Then, just as the crane was lifting the sub into the water, a crew member took Cameron aside. A call had come in to the ship. Moments later Cameron radioed Allum. “Abort the dive,” he said.

“We just got word from the airport,” he told the crew on deck. “The helicopter has gone down. Andrew and Mike were inside.” He paused, seeking the right words. “They should be OK. People walk away from most helicopter accidents.”

They didn’t walk away. The helicopter crashed and burned shortly after takeoff. Wight and deGruy were dead.

Two weeks passed in sorrow and remembrance. Aboard Mermaid SapphireCameron took the measure of his expedition mates, rough-and-tumble types accustomed to adapting on the fly. David Wotherspoon, a gruff ex-special forces soldier experienced in building and operating submersibles, was project manager and deck officer. Garvin, a British rebreather-diving instructor, managed the sub’s life-support systems. Bruce Sutphen, a Southern California veteran of America’s Cup design teams, had helped build the sub. Cameron called in Charlie Arneson, a marine biologist and logistics wizard who developed the 20th Century Fox film studio in Rosarito Beach, Mexico, used to film Titanic. Douglas Bartlett, a microbiologist who studied organisms in extreme environments, signed on as the expedition’s chief scientist. Then there was Don Walsh, the only man alive with previous experience diving Challenger Deep. To a person, they implored him to press on.

“Giving up and quitting wasn’t part of Andrew’s DNA,” said Garvin, who was also Wight’s brother-in-law. Cameron agreed. “Andrew would’ve kicked our asses if we’d shut it down,” he said. “Let’s move forward.”

The expedition regrouped in Papua New Guinea, where, on February 21, DEEPSEA CHALLENGER finally swung over the rail on its first deepwater launch. From the moment the craft touched water, things went haywire. The electrical system flashed off and on. The carbon dioxide scrubber fell off the wall into Cameron’s lap as he sat in the sub’s cockpit. The 3-D cameras failed. Cameron aborted the dive. Even the abort went pear-shaped. The safety divers couldn’t rotate the sub into recovery position. “Lying on my side here,” Cameron said into the radio, clearly irritated. “Not helping matters.”

An hour later, the sub cradled on deck, launch boss Wotherspoon gathered the engineering team on the bridge. Cameron arrived still wearing his sweat-damp dive shirt.

“The scrubber, that one’s on me,” Garvin told him. “I should have put two shackles on it.” Somebody made a joke about a ten-dollar shackle scuttling a quarter-million-dollar dive.

“You can take it out of my wages, Jim,” Garvin said.

“I’ll be taking it out of your wages for the next 20 years,” Cameron said. Laughter broke the tension. As a film director Cameron had a reputation for driving his crew hard. On expeditions, he tried to convert that ferocity into forward progress. “Improvise, adapt, overcome,” he said. “Works for the Marines, works for us here on the ship.”

Twenty-four hours passed. Another dive attempted. Another dive aborted. On the third day, the sub finally launched. Cameron sank swiftly to the seafloor, where he spent three hours observing eels and bizarre holothurians at a depth of a thousand meters. When he was ready to ascend, he alerted Mermaid Sapphire. “Dropping weights,” he said. A burst of data came into the comms center. “Be advised,” said the ship’s captain, Stuart Buckle. “Sub is ascending at 5.5 knots. She’s gonna make a splash.”

Garvin frowned. “That’s too fast,” he said. Visions of velocity ripping apart the sub. “That’s three times faster than Trieste came up.”

Allum relaxed in his chair. He waved off Garvin’s worry. She was built for this, mate.

“One hundred meters to surface,” shouted Captain Buckle.

At the rail two dozen eyes scanned the dark horizon. Two hundred yards off to starboard a fountain of light grew from the sea. DEEPSEA CHALLENGER, lights blazing, erupted like a spy-hopping whale. Amid shouts of joy, Garvin stood quietly at the bridge rail, his closed fist trembling in triumph and relief.

An hour later in the galley, Cameron reassured Garvin about the screaming ascent. “I wanted to test the sub,” he said. “I dropped the descent weights, all my shot ballast, and went full up on the thrusters. Then I thought, ‘Jeez, I hope this thing holds together.’ Because that thing was shaking on the way up.” His smile warmed the room.

As team members drifted away to their bunks, Cameron reflected on the milestone. “After the loss of Andrew and Mike, we needed a comeback,” he said. “We needed a win. Tonight we got it.”

The next afternoon, logistics manager Charlie Arneson glanced at the expedition calendar. Four weeks in, three dives done. A few days later, they dived again, this time to 3,658 meters. But due to bad weather, mechanical problems, and sheer grief, they had fallen behind schedule. They had booked Mermaid Sapphire only to the end of March, when Cameron was committed to be in London for the premiere of the 3-D version of Titanic. DEEPSEA CHALLENGER had traveled only a third of the way to Mariana Trench depth. And their weather window was closing. In the galley, Sutphen checked wind-speed data on his laptop. “I hope everyone packed their foulies,” he said, referring to foul-weather gear. “It’s really nuking at the trench.”

Mindful of the ticking clock, Cameron skipped his planned 6,000-meter dive and went straight to an 8,000-meter attempt in the New Britain Trench east of New Guinea. This would be the last big test before the Mariana Trench. On the morning of the dive Garvin worried about the risk as he packed fresh soda lime into the pilot’s CO₂ scrubber. “If she comfortably reaches 8,000, she’ll probably go to full ocean depth.”

That night, DEEPSEA CHALLENGER made it to 7,260 meters (23,800 feet, about 4.5 miles) before a software glitch forced Cameron to return to the surface. “We’ll turn it around in 48 hours and dive the full 8K,” he told Wotherspoon.

These stairstep dives weren’t only about testing the sub. “You don’t go to the moon to prove that the rocket ship works,” Cameron told his team. The point was to explore, to obtain video footage and scientific samples. “Everything we bring back from these depths is treasure to the scientific community,” he said.

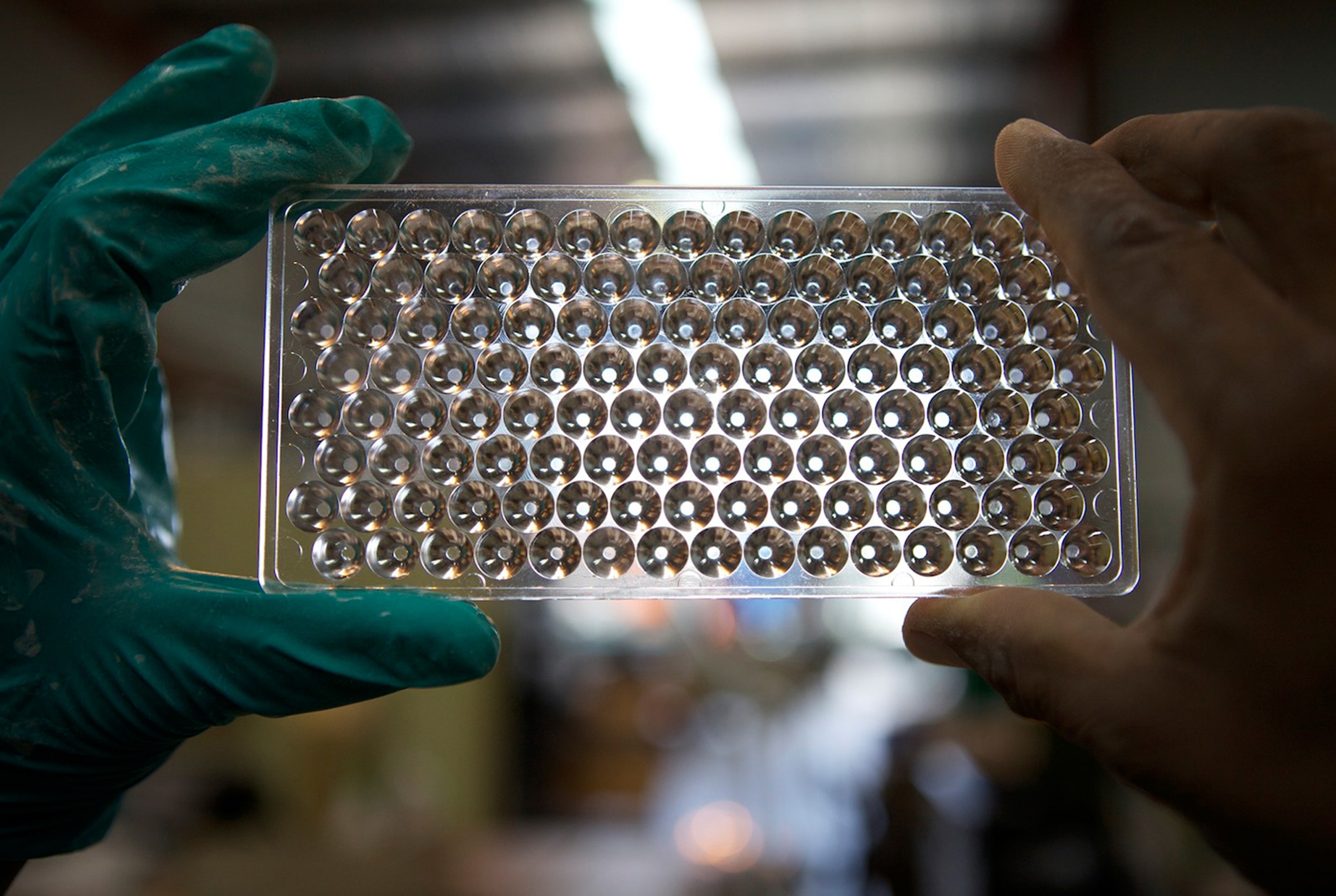

Bartlett, the expedition’s lead scientist, had a lab set up to receive those diamonds and pearls. After each dive he quickly transferred DEEPSEA CHALLENGER’s samples to pressurized collection vessels. “We have so little data about the diversity of life at these extreme hadal depths,” he said. “Any water or sediment samples Jim can give us, even as little as ten milliliters”—about two teaspoons—“will be extremely valuable. Hadal life-forms are among the least known organisms on the planet.”

Hadal trenches are utterly dark, near-freezing habitats. The crushing water pressure prevents organisms from absorbing the minerals needed to form bones or shells. Bartlett hoped to discover the adaptations microbes had made to survive in such an inhospitable place. On Cameron’s next dive, Bartlett hit the jackpot. A trap returned from 8,221 meters writhing with dozens of gigantic amphipods, prawnlike creatures with eerie white shells. They’d stripped the bait—a whole raw chicken—down to clean bone. Bartlett could hardly believe his eyes. “These are the largest I’ve ever seen,” he said, holding a trout-size sample.

A rush of adrenaline hit Mermaid Sapphire. The science was coming through. The sub was hitting its marks. Next stop: the Mariana Trench.

A five-day passage to Guam gave the expedition a bitter taste of the open sea.Mermaid Sapphire reared and rolled. The engineering workshops turned into carnival rides. Bolts, wrenches, and screwdrivers spilled out of their bins. When the ship pulled into Apra Harbor, logistics chief Charlie Arneson charged into town in search of scopolamine patches, strong medicine for the expedition’s seasick members.

Storms at the trench kept Mermaid Sapphire hugging the shore. The weeklong weather delay put the expedition on edge. Then on March 20, a potential clearing appeared in the forecast. Captain Buckle set a course for the Challenger Deep, more than 200 miles out to sea. But when the ship arrived above the dive spot, the expected clearing did not come.

Captain Buckle retreated to the lee of Ulithi, a remote atoll famous for hiding part of the U.S. Pacific Fleet during the waning months of World War II. More days passed as thick swells rolled above the trench. Time was running out.

Cameron paced the ship, checked on the sub, plotted and replotted his seafloor route. “It’s hard to be patient when your adrenaline is up,” he said. He glanced at his watch. “Now we’ve got no choice but to run right up to our deadline.”

Doubt scented the air. Everybody sensed it, few acknowledged it. The weather window was closing. Cameron’s London commitment loomed. If he didn’t get the sub in the water soon, he might never dive the trench. Minutes and seconds began to count.

In the early evening of March 25, launch boss Wotherspoon stood with Captain Buckle on the bridge. They used their bodies as sway meters, imagining a 12-ton sub hanging on the end of a crane wire. Two words came to mind: wrecking ball. Diving was out of the question. “Jim’s waited seven years,” Buckle said. “What’s one more day?”

After conferring with Wotherspoon, Cameron set the call for predive checks for midnight, with a dive target just before dawn. It would be the only chance. At 4 a.m., Cameron appeared on deck dressed in his dive suit: A sweat-wicking shirt, neoprene booties, a jaunty-Jacques watch cap. He checked in with Ron Allum. “Just an elevator ride, eh, Ronnie?”

Cameron kissed his wife, Suzy Amis. “Bye, Babe. See you in the sunshine.” He folded his body into the capsule. Garvin lowered the hatch and sealed him in.

As the ship’s crane lifted it over the rail, DEEPSEA CHALLENGER bucked like a rodeo bull. A machine built for deep water, it always seemed to fight against the harness lift. Garvin, standing nearby, offered a soothing word. “C’mon, baby,” he whispered. “Big job to do.”

Sealed in a steel capsule, Cameron bobbed in the swells, drifting in the current toward their target location for the descent. Beneath him: nearly seven miles of water. In the comms center, Tim Bulman counted him down to release. “Ten minutes to drop point, Jim.”

“Roger that,” Cameron said.

Wotherspoon and the launch team, exhausted and wired, leaned at Mermaid Sapphire’s starboard rail. Eyes locked on the green machine, ears tuned to the radio countdown.

“Seven minutes, Jim.”

Then, crisis. A big swell blew open a hatch containing a large orange ballast balloon, which bobbed to the surface.

This was a potential showstopper. Without the ballast, Cameron could easily find himself marooned below the surface. On Mermaid Sapphire hearts seized. The expedition team awaited Wotherspoon’s dreadful order: Abort the dive. Try again tomorrow. But they had no spare tomorrows.

“We’ve got a soft ballast deploy,” Cameron said over the radio.

“Yeah, I can see that,” Wotherspoon replied.

Seconds passed. The chop slapped Mermaid Sapphire’s bow.

Cameron’s voice came over the radio.

“Cut it away,” he said. “I’m going to dive without it.”