40 years after Solidarity, Gdańsk's rebellious spirit still inspires Poland

The Baltic seaport is a city of grit, elegance, and memories of the labor strike that turned the nation toward democracy.

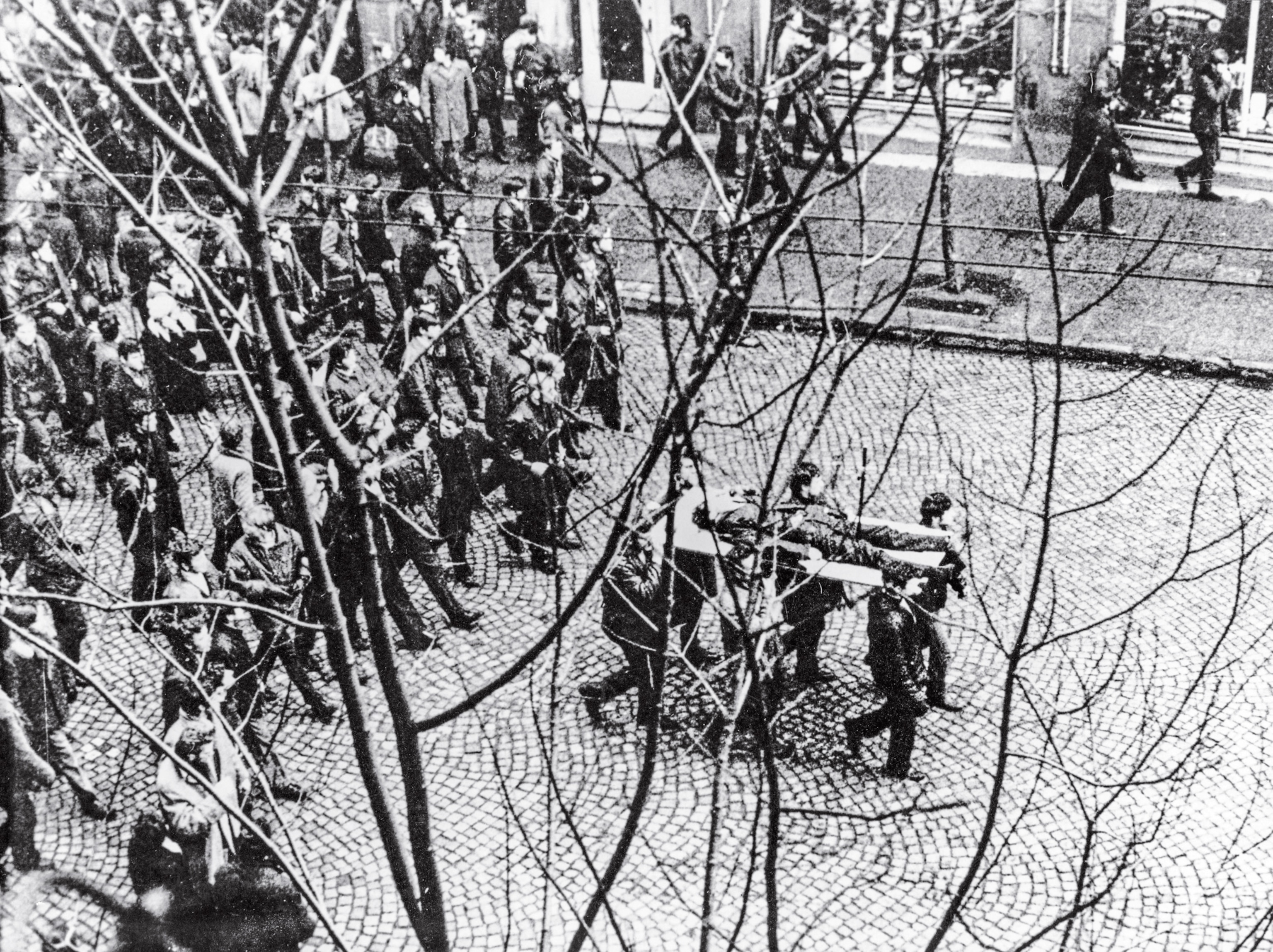

For the longest time, I associated the city of Gdańsk with my police detention. It was December 16, 1982, and a year earlier the communist authorities had imposed martial law.

They were signaling an easing of restrictions by releasing the Solidarity trade union leader Lech Wałęsa after 11 months of internment. A government spokesman smugly described him as “the former head of a former union.” Wałęsa was due to give a speech that day, and about 40 of us—foreign correspondents, photographers, and our Polish assistants—were clustered next to the entrance to his apartment block, expecting to go inside for an interview.

Instead, police barred us from entering. Because Solidarity was banned at the time, Wałęsa’s speech and our attempt to see him were deemed illegal. The face-off was at first alarming—many Poles had been imprisoned during the crackdown. But the tension gave way to comic relief. You see, I was four months pregnant, and particularly the Poles in our group were outraged that the police would subject me to any stress, much less detention—and they let the officers know it. Soon it seemed that half the apartment complex had heard I was with child. Women stopped to bawl out the police, who accepted this dressing-down with quiet embarrassment. In those times few Poles felt friendly toward the authorities, and it must have been cathartic to lecture these representatives of power on proper Polish behavior. Still, we were crammed into windowless vans and transported to the station. There we were merely warned to stay away from Wałęsa and released.

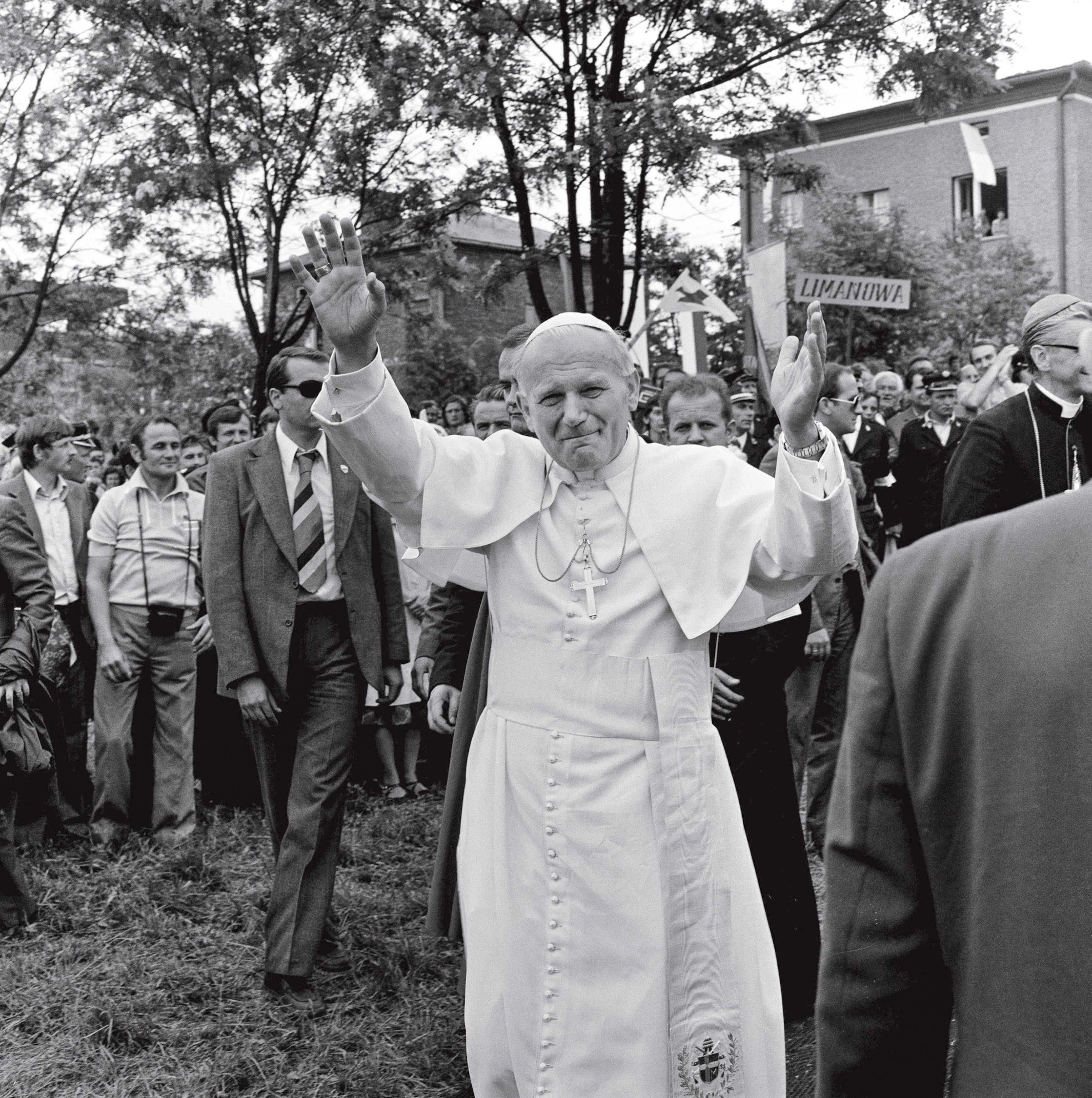

Now I am back in Gdańsk. It’s been 40 years since the August shipyard strikes that birthed the Solidarity movement, setting Poland on the road to democracy. Those strikes drew journalists like me to the country to cover the peaceful revolution. Based in Warsaw for three years, I reported on the rise of the 10 million–strong union. While on a fellowship in 1989 I chronicled the compromise between the opposition and the communist party that led to partially free elections—and a landslide victory for Solidarity. The country has since adopted a new constitution, protecting the independence of the judiciary and other institutions, but the present government is widely seen as undermining these democratic foundations.

In this Baltic seaport, with a history of trading goods, people, and ideas dating to the Middle Ages, perhaps not revolution but certainly rebellion is still alive. The city has defied the ruling Law and Justice party and gained a reputation for tolerance. When Poland refused to accept refugees as part of the European Union resettlement plan, Gdańsk said it would welcome them. And when the leader of the ruling party, Jarosław Kaczyński, called LGBT ideology a threat to Polish identity and a “massive storm of evil,” city officials vowed to protect sexual minorities.

If Gdańsk is the opposition city, the European Solidarity Centre is its heart. It’s a living monument to the trade union and the legacy of the strikes, which ended nearby at the historic Gate No. 2 to the Gdańsk Shipyard, also known then as the Lenin Shipyard. Wałęsa has an office on the second floor. When I meet with him, he’s wearing a gray shirt emblazoned with the word KONSTYTUCJA. He has many versions of this shirt and even wore one to President George H. W. Bush’s state funeral. Its message: The ruling party has trampled basic constitutional rights. The state-controlled media has choice words for Wałęsa too, depicting him as a traitor and a has-been.

After cordial greetings, Wałęsa deepens his voice and briskly says, “Pierwsze pytanie”—first question—as if he’s pressing a stopwatch to begin a race. Does he have somewhere to go, or is it simply a way of taking command? But he patiently responds when I ask about the moment he entered the shipyard on August 14, 1980. He recalls it as “a certain stage, a certain moment,” adding, “I expected it wasn’t the last stage in my fight.” In his negotiations, he tells me, “as I knew that I wasn’t going to win too much, I was trying to act so as not to lose too much.”

At one point during our conversation, I interject with a friendly wisecrack: “I know you weren’t on a motorboat.” It’s a reference to allegations he showed up in a military boat after the strike was under way. The claim, made by some of his critics, seeks to prove police collaboration. Wałęsa limits his rebuttal to a roll of his eyes.

We go back to the meaning of his shirt. He suggests Poland fits a global trend toward declining democratic values. He singles out laws that the ruling party pushed through parliament curbing the independence of the courts. “For me also, the judicial system and other actions were an obstacle,” he admits, recalling the challenges he faced when he was president from 1990 to 1995. But he says he didn’t try to “liquidate” the independent judiciary. “Once you eliminate one obstacle, then you need to eliminate the next obstacle. That’s how dictatorships emerge.”

Gdańsk is both grit and elegance. Around the port’s industrial zone, the skyline is a tangle of cranes, lifting hooks, and smokestacks. Here and there, pockmarks left from World War II are visible on facades. In the city center, however, the skyline is a pristine panorama of church spires, towers, and red-tile roofs. The streetscape, too, is marvelously Old World, thanks to a painstaking postwar reconstruction effort.

Ulica Długa, the main pedestrian walkway, is rightfully considered the crown jewel. The street is lined with rebuilt 16th- and 17th-century Flemish-style buildings with ornate gables topped with sculptures, urns, and finials. They are suitably grand for the Dutch merchant princes and others who made fortunes shipping grain. For centuries, Gdańsk—or Danzig, as it was called for most of its history—was a cosmopolitan and prosperous city. As a member of the Hanseatic League, a trading alliance that began in the 12th century, it was linked to ports as disparate as London and Novgorod.

Nearby is the famous Złota Brama, the Golden Gate, built in the first part of the 17th century and reconstructed after it was destroyed in World War II. With its huge two-story windows and classical columns, it’s eye-catching, but I am headed for a simple, black marble plaque, set in the pavement nearby. It reads, “Gdańsk is generous. Gdańsk shares its good. Gdańsk wants to be a city of solidarity”—words spoken by Mayor Paweł Adamowicz moments before he was savagely stabbed in this area in front of an audience of hundreds in January 2019, an assault that killed him. The attacker had a history of violent crime, but to many in Gdańsk, the assassination reflected the febrile political climate that pitted their city’s vision of openness against the aggrieved nationalism and vitriol of the ruling party.

“Our situation here is so sharp right now,” says Julia Borzeszkowska, a 20-year-old first-year law student at Gdańsk University. “The violence and hate is so strong that it pushed someone to murder another person.” In her last year of high school, Borzeszkowska organized a protest called March Beyond Divisions, which drew 1,500 young people into the streets.

As she peers out from oversize wire-rimmed eyeglasses, Borzeszkowska’s direct, blunt words belie the quavering in her voice. “My generation was raised believing in freedom, solidarity, and fighting for democracy. We learned this from our parents and grandparents. These issues were important to them, and they are important for us right now.” She speaks with utter conviction, and I am reminded of the forthrightness of the early Solidarity activists. May I use your name? I would ask, and usually the answer would be yes, despite the danger. I was told more than once: I want my children to know what I stood for.

Borzeszkowska vows she will return to activism, and I believe her.

The mayor’s murder also brought thousands of people to the streets in Gdańsk and Warsaw. Aleksandra Żurowska—a prominent Gdańsk physician who, with her daughter Joanna Lisiecka-Żurowska, introduced me to people in the city—recalls the outpouring of grief. Friends from all over Poland called to commiserate. “They were telling me: We are looking at what’s happening in Gdańsk, and we are waiting again. Always Gdańsk leads us in these moments.”

Though the assassination was 14 months before my visit, the subject comes up often, even in casual exchanges. It’s clearly seen as a moment of reckoning for the city and its ideals. “In my daily life I do not dwell on that horrible Sunday,” says the current mayor, Aleksandra Dulkiewicz, who also supports progressive causes and welcoming non-Poles. Now many towns and cities in Poland follow what’s called the Gdańsk model of integrating foreigners. That embrace of newcomers—of 460,000 citizens, about 25,000 are immigrants from the former Soviet Union, Rwanda, and Syria—is consistent with the city’s past, notes Aleksander Hall, a historian and Gdańsk native.

“One unique aspect of Gdańsk was that it was always a multicultural city,” he explains. As a port, it was a freewheeling commercial hub, welcoming traders and other foreigners from many countries, particularly Germans, but also Scots, the Dutch, and the English. During Gdańsk’s Reformation in the 1600s, it sheltered persecuted religious groups—Dutch Mennonites as well as Huguenots and Jews. Because of the city’s growing ethnic mix, that heritage is being reborn, Hall says.

There is a famous line from a novel by William Faulkner that I first learned in Poland, when a journalist friend, Jacek Kalabiński, quoted it to explain why Poles seem fixated on painful chapters of their history. “The past is never dead. It’s not even past.” Those sentences run through my head as I learn about state efforts to control the historical narrative in Gdańsk. The city’s World War II museum had its founding director and curators pushed out by the Ministry of Culture, which objected that the exhibits were “not Polish enough.”

Lisiecka-Żurowska and I talk about the war while traveling on the train to Gdańsk. She grew up there, and her family story speaks to the complexities of the conflict as it played out in her hometown. On the eve of the war, the city was predominantly German-speaking but had an established Polish community. It had received special status as a free city after World War I; Poles were given control of the railways and access to the port. On September 1, 1939—the start of World War II—a German battleship fired on a Polish garrison, which held out for seven days despite being outgunned. Lisiecka-Żurowska’s great-grandmother’s husband and three brothers, members of the educated elite, were arrested and sent to concentration camps, where they died.

By the end of the war, most of the city lay in ruins. What was left of the German population fled or was expelled. Poles were forcibly removed from areas such as Ukraine (annexed by the Soviet Union) and resettled around Poland. People in search of jobs—Wałęsa told me most were ambitious youth who felt suffocated by small-town life—flocked to Gdańsk to work in the shipyards and other industries. Wałęsa’s wife, Danuta, recalls turning to her mother before boarding a bus leaving her village and blurting out, “I will not come back here.”

That fierce determination is still part of Danuta Wałęsa, though she endured many unhappy years when her husband was battling the authorities. A friend of a friend arranges a meeting, and we sit at the dining room table in her light-filled family home. I remind her that we’d met in the days when the old apartment was jammed with visitors waiting for a word with Lech. I mention that I always tried to greet her, but she often seemed out of sorts, even angry. She’s shaken by my comment, and her eyes well with tears. She had six children at the time of the shipyard strikes and felt isolated and alone. “I don’t know how I had the strength to survive all this,” she tells me.

But she more than survived. In 2011 she published a best-selling memoir that described a hollowed-out marriage. Nonetheless, she’s protective of her husband and condemns the ruling party’s attacks on him. “It is absolutely outrageous,” she says. “This government doesn’t recognize him, and they want to say he is nobody.” Seeing the flash of anger in her eyes, I’m reminded of the women at the apartment complex and their feisty defense of a pregnant woman.

Danuta believes the country is ripe for change, but fears there isn’t a leader to rally the opposition. “The country needs a second Wałęsa,” she says. And not just a second Wałęsa, she underscores, but one with a strong core of supporters and advisers like her husband had when he fought the communist regime. Though she warns of dangers ahead—“We need to stand up like before, or something terrible will happen”—she’s confident that when change does come, it will be her city that leads: “There is no braver place in Poland than Gdańsk.”