The Telltale Scribes of Timbuktu

The caravan city harbors great books, mysterious letters—and a world of intrigue.

The Salt Merchant

In the ancient caravan city of Timbuktu, many nights before I encountered the bibliophile or the marabout, or comforted the Green Beret's girlfriend, I was summoned to a rooftop to meet the salt merchant.

I had heard that he had information about a Frenchman who was being held by terrorists somewhere deep in the folds of Mali's northern desert. The merchant's trucks regularly crossed this desolate landscape, bringing supplies to the mines near the Algerian border and hauling the heavy slabs of salt back to Timbuktu. So it seemed possible that he knew something about the kidnappings that had all but dried up the tourist business in the legendary city.

I arrived at a house in an Arab neighborhood after the final call to prayer. A barefoot boy led the way through the dark courtyard and up a stone staircase to the roof terrace, where the salt merchant was seated on a cushion. He was a rotund figure but was dwarfed by a giant of a man sitting next to him who, when he unfolded his massive frame to greet me, stood nearly seven feet tall. His head was wrapped in a linen turban that covered all but his eyes, and his enormous warm hand enveloped mine.

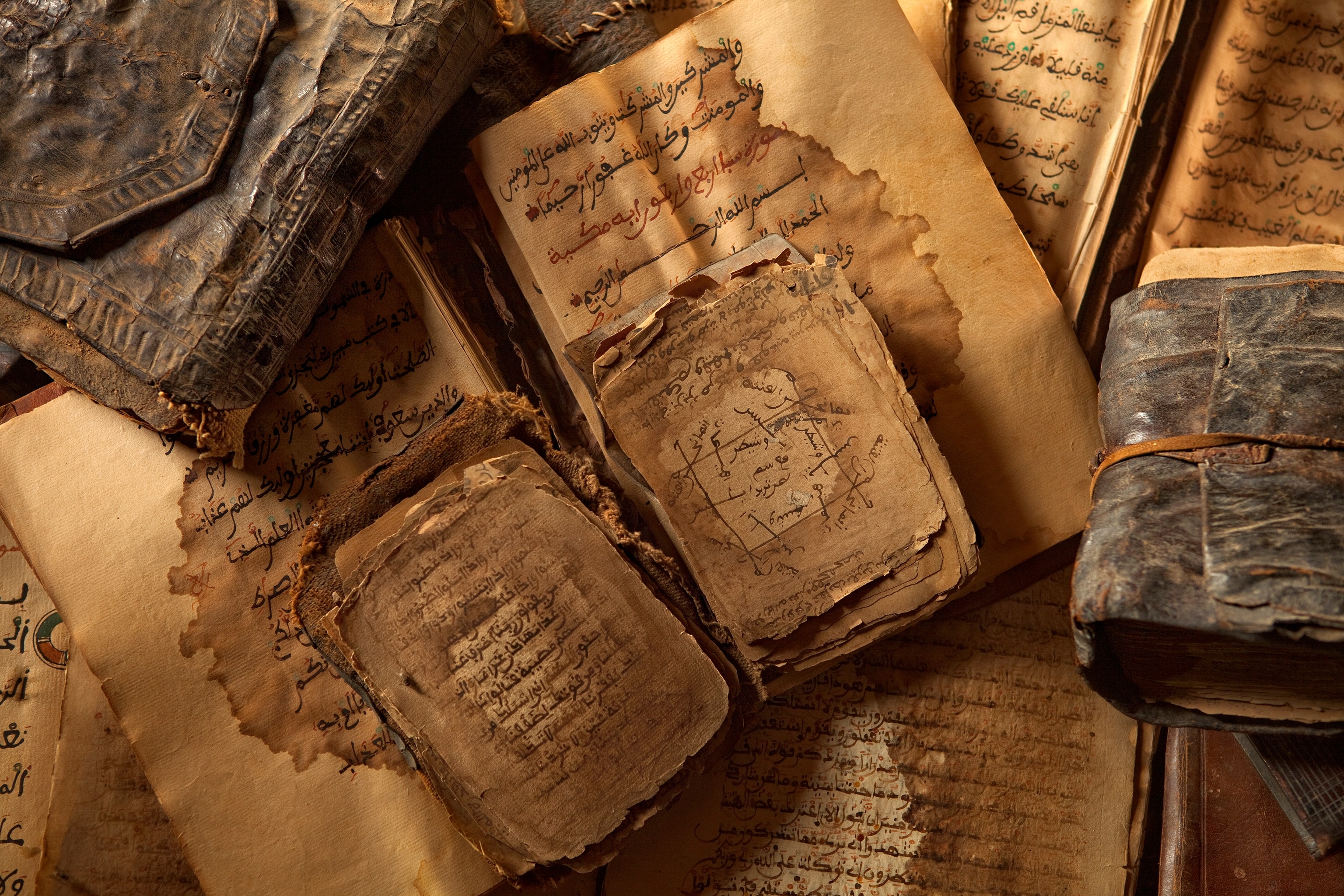

We patiently exchanged pleasantries that for centuries have preceded conversations in Timbuktu. Peace be upon you. And also upon you. Your family is well? Your animals are fat? Your body is strong? Praise be to Allah. But after this prelude, the salt merchant remained silent. The giant produced a sheaf of parchment, and in a rich baritone slightly muffled by the turban over his mouth, he explained that it was a fragment of a Koran, which centuries ago arrived in the city via caravan from Medina. "Books," he said raising a massive index finger for emphasis, "were once more desired than gold or slaves in Timbuktu." He clicked a flashlight on and balanced a mangled pair of glasses on his nose. Gingerly turning the pages with his colossal fingers, he began to read in Arabic with the salt merchant translating: "Do men think they will be left alone on saying, 'We believe,' and that they will not be tested? We did test those before them, and Allah will certainly know those who are true from those who are false."

I wondered what this had to do with the Frenchman. "Notice how fine the script is," the giant said, indicating the delicate swirls of faded red and black ink on the yellowing page. He paused, "I will give it to you for a good price." At this point I fell into the excuses that I regularly used with the men and boys hawking silver jewelry near the mosque. I thanked him for showing me the book and told him that it was far too beautiful to leave Timbuktu. The giant nodded politely, gathered the parchment, and found his way down the stone stairs.

The salt merchant lit a cigarette. He had a habit of holding the smoke in his mouth until he spoke so that little puffs would tumble out along with his words. He explained that the giant did not really want to sell the manuscript, which had been passed down through his mother's ancestors, but that his family needed the money. "He works for the guides, but there are no tourists," he said. "The problems in the desert are making all of us suffer." Finally, he mentioned the plight of the Frenchman. "I have heard the One-Eye has set a deadline."

During my time in Timbuktu, several locals denied that the city was unsafe and beseeched me to "tell the Europeans and Americans to come." But for much of the past decade the U.S. State Department and the foreign services of other Western governments have advised their citizens to avoid Timbuktu as well as the rest of northern Mali. The threats originate from a disparate collection of terrorist cells, rebel groups, and smuggling gangs that have exploited Mali's vast northern desert, a lawless wilderness larger than France and dominated by endless sand and rock, merciless heat and wind.

Most infamous among the groups is the one led by Mokhtar Belmokhtar, an Algerian leader of al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM). Reputed to have lost an eye fighting the Russians in Afghanistan, he is known throughout the desert by his nom de guerre, Belaouer, Algerian-French slang for the One-Eye. Since 2003, his men have kidnapped 47 Westerners. Until 2009, AQIM had reached deals to release all of its hostages, but when the United Kingdom refused to meet the group's demands for Edwin Dyer, a British tourist, he was executed—locals say beheaded. His body was never found. In the weeks before my arrival, Belaouer and his cohorts had acquired a new inventory of hostages: three Spanish aid workers, an Italian couple, and the Frenchman.

"Belaouer is very clever," the salt merchant emphasized. He described how AQIM gained protection from the desert's Arab-speaking clans through Belaouer's marriage to the daughter of a powerful chief. One popular rumor describes him giving fuel and spare tires to a hapless Mali army patrol stranded in the desert. Such accounts have won him sympathizers among Timbuktu's minority Arab community, which in turn has angered the city's dominant ethnic groups, the Tuareg and Songhai.

Up on the roof the temperature had dropped. The salt merchant pulled a blanket around his shoulders and drew deeply on his cigarette. To the north, the city's lights gave way to the utter blackness of the open desert. He told me that the price AQIM had set for the Frenchman's life was freedom for four of its comrades arrested by Malian authorities last year. The deadline to meet these demands was four weeks away.

I asked him why the Mali army did not mount an offensive against the terrorists. He pointed the red ember of his cigarette toward a cluster of houses a few streets over and described how Belaouer's men had assassinated an army colonel in front of his young family in that neighborhood a few months earlier. "Everyone in Timbuktu heard the shots," he said quietly. He mimicked the sound, bang, bang, bang. Then he waved the cigarette over the constellation of electric lights that revealed the shape of the city. "The One-Eye has eyes everywhere." And then, almost as an afterthought, he added, "I'm sure he knows you are here."

The Bibliophile

Sand blown in from the desert has nearly swallowed the paved road that runs through the heart of Timbuktu to Abdel Kader Haidara's home, reducing the asphalt to a wavy black serpent. Goats browse among trash strewn along the roadside in front of ramshackle mud-brick buildings. It isn't the prettiest city, an opinion that has been repeated by foreigners who have arrived with grand visions ever since 1828, when R&eacuta;né Caillié became the first European to visit Timbuktu and return alive. Yet it is a watchful city: With every passing vehicle, children halt soccer games, women pause from stoking adobe ovens, and men in the market interrupt their conversations to note who is riding by. "It is important to know who is in the city," my driver said. Tourists and salt traders mean business opportunities; strangers could mean trouble.

I found Haidara, one of Timbuktu's preeminent historians, in the blinding mid-morning glare of his family's stone courtyard, not far from the Sankore Mosque. He wanted to show me what he said was the first documentary evidence of democracy being practiced in Africa, a letter from an emissary to the sheikh of Masina. The temperature was quickly approaching 100°, and he sweated through his loose cotton robe as he moved dozens of dusty leather trunks, each containing a trove of manuscripts. He unbuckled the strap of a trunk, pried it open, and began carefully sorting the cracked leather volumes. I caught a pungent whiff of tanned skins and mildew. "Not in here," he muttered.

Haidara is a man obsessed with the written word. Books, he said, are ingrained in his soul, and books, he is convinced, will save Timbuktu. Words form the sinew and muscle that hold societies upright, he argued. Consider the Koran, the Bible, the American Constitution, but also letters from fathers to sons, last wills, blessings, curses. Thousands upon thousands of words infused with the full spectrum of emotions fill in the nooks and corners of human life. "Some of those words," he said triumphantly, "can only be found here in Timbuktu."

It is a practiced soliloquy but a logical point of view for a man whose family controls Timbuktu's largest private library, with some 22,000 manuscripts dating back to the 11th century and volumes of every description, some lavishly illuminated in gold and decorated with colorful marginalia. There are diaries filled with subterfuges and plots, as well as correspondence between sovereigns and their satraps, and myriad pages filled with Islamic theology, legal treatises, scientific notations, astrological readings, medicinal cures, Arabic grammar, poetry, proverbs, and magic spells. Among them are also the little scraps of paper that track the mundanities of commerce: receipts for goods, a trader's census of his camel herd, inventories of caravans. Most are written in Arabic, but some are in Haidara's native Songhai. Others are written in Tamashek, the Tuareg language. He can spend hours sitting among the piles, dipping into one tome after another, each a miniature telescope allowing him to peer backward in time.

The mosaic of Timbuktu that emerges from his and the city's other manuscripts depicts an entrepôt made immensely wealthy by its position at the intersection of two critical trade arteries—the Saharan caravan routes and the Niger River. Merchants brought cloth, spices, and salt from places as far afield as Granada, Cairo, and Mecca to trade for gold, ivory, and slaves from the African interior. As its wealth grew, the city erected grand mosques, attracting scholars who, in turn, formed academies and imported books from throughout the Islamic world. As a result, fragments of the Arabian Nights, Moorish love poetry, and Koranic commentaries from Mecca mingled with narratives of court intrigues and military adventures of mighty African kingdoms.

As new books arrived, armies of scribes copied elaborate facsimiles for the private libraries of local teachers and their wealthy patrons. "You see?" said Haidara, twirling his hand with a flourish. "Books gave birth to new books."

Timbuktu's downfall came when one of its conquerors valued knowledge as much as its own residents did. The city never had much of an army of its own. After the Tuareg founded it as a seasonal camp about A.D. 1100, the city passed through the hands of various rulers—the Malians, the Songhai, the Fulani of Masina. Timbuktu's merchants generally bought off their new masters, who were mostly interested in the rich taxes collected from trade. But when the Moroccan army arrived in 1591, its soldiers looted the libraries and rounded up the most accomplished scholars, sending them back to the Moroccan sultan. This event spurred the great dispersal of the Timbuktu libraries. The remaining collections were scattered among the families who owned them. Some were sealed inside the mud-brick walls of homes; some were buried in the desert; many were lost or destroyed in transit.

It was Haidara's insatiable love for books that first led him to follow his ancestors into a career as an Islamic scholar and later propelled him into the vanguard of Timbuktu's effort to save the city's manuscripts. Thanks to donations from governments and private institutions around the world, three new state-of-the-art libraries have been constructed to collect, restore, and digitize Timbuktu's manuscripts. Haidara heads one of these new facilities, backed by the Ford Foundation, which houses much of his family's vast collection. News of the manuscript revival prompted the Aga Khan, an important Shiite Muslim leader, to restore one of the city's historic mosques and Libyan leader Muammar Qaddafi to begin building an extravagant walled resort in anticipation of future academic congresses.

I asked Haidara if the problems in the desert are impeding Timbuktu's renaissance. "Criminals, or whoever else it may be, are the least of my worries," he said, pointing to pages riddled with tiny oblong holes. "Termites are my biggest enemies." Scholars estimate many thousands of manuscripts lie buried in the desert or forgotten in hiding places, slowly succumbing to heat, rot, and bugs. The question of what might be lost haunts Haidara. "In my worst dreams," he said, "I see a rare text that I haven't read being slowly eaten."

The Marabout

After the salt merchant's talk about the One-Eye, a local man suggested I consult a certain marabout, a type of Muslim holy man. For a price, he could provide me with a gris-gris, a small leather pouch containing a verse from the Koran imbued by the marabout with a protective spell. "He is the only one who can truly protect you from Belaouer," the man had confided.

Arriving at the marabout's house, I entered a small anteroom where a thin, bedraggled man was crouching on the dirt floor. He reached out and firmly held one of my hands in both of his. A few of his fingernails had grown long and curved off the tips of his fingers like talons. "Peace upon you," the man cried out. But after I returned his greeting, he didn't let go of my hand. Instead he sat on the ground, rocking slightly back and forth, firmly holding on, and smiling up at me. Then I noticed a chain fastened around his ankle. It snaked across the floor to an iron ring embedded in the stone wall.

The marabout, a balding man in his late 40s, who wore reading glasses on a string around his neck, appeared. He politely explained that the chained man was undergoing a process that would free him from spirits that clouded his mind. "It is a 30-day treatment," he said. He reached out and gently stroked the crouching man's hair. "He is already much better than he was when he arrived."

The marabout led the way to his sanctum, and my translator and I followed him across a courtyard, passing a woman and three children who sat transfixed in front of a battered television blaring a Pakistani game show. We ducked through a bright green curtain into a tiny airless room piled with books and smelling of incense and human sweat. The marabout motioned us to sit on a carpet. Gathering his robes, he knelt across from us and produced a matchstick, which he promptly snapped into three pieces. He held them up so that I could see that they were indeed broken and then rolled up the pieces in the hem of his robe. With a practiced flourish worthy of any sleight-of-hand expert, he unfurled the garment and revealed the matchstick, now unbroken. His powers, he said, had healed it. My translator excitedly tapped my knee. "You see," he said, "he is a very powerful marabout." As if on cue, applause erupted from the game show in the courtyard.

The marabout retrieved a palm-size book bound with intricately tooled leather. The withered pages had fallen out of the spine, and he gently turned the brittle leaves one by one until he found a chart filled with strange symbols. He explained that the book contained spells for everything from cures for blindness to charms guaranteed to spark romance. He looked up from the book. "Do you need a wife?" I said that I already had one. "Do you need another?"

I asked if I could examine the book, but he refused to let me touch it. Over several years his uncle had tutored him in the book's contents, gradually opening its secrets. It contained powers that, like forces of nature, had to be respected. He explained that his ancestors had brought the book with them when they fled Andalusia in the 15th century after the Spanish defeated the Moors. They had settled in Mauritania, and he had only recently moved from there with his family. "I heard the people of Timbuktu were not satisfied with the marabouts here," he said. I asked who his best customers were. "Women," he answered, grinning, "who want children."

He produced a small calculator, punched in some numbers, and quoted a price of more than a thousand dollars for the gris-gris. "With it you can walk across the entire desert and no one will harm you," he promised.

The Green Beret’s Girlfriend

The young woman appeared among the jacaranda trees of the garden café wearing tight jeans and a pink T-shirt. She smiled nervously, and I understood how the Green Beret had fallen for her. Aisha (not her real name) was 23 years old, petite, with a slender figure. She worked as a waitress. Her jet black skin was unblemished except for delicate ritual scars near her temples, which drew attention to her large, catlike eyes.

We met across from the Flame of Peace, a monument built from some 3,000 guns burned and encased in concrete. It commemorates the 1996 accord that ended the rebellion waged by Tuareg and Arabs against the government, the last time outright war visited Timbuktu.

Aisha pulled five tightly folded pieces of paper from her purse and laid them on the table next to a photograph of a Caucasian man with a toothy smile. He appeared to be in his 30s and was wearing a royal blue Arab-style robe and an indigo turban. "That is David," she said, lightly brushing a bit of sand from the photo.

They had met in December 2006, when the U.S. had sent a Special Forces team to train Malian soldiers to fight AQIM. David had seen her walking down the street and remarked to his local interpreter how beautiful she was. The interpreter arranged an introduction, and soon the rugged American soldier and the Malian beauty were meeting for picnics on the sand dunes ringing the city and driving to the Niger River to watch the hippos gather in the shallows. Tears welled in Aisha's eyes as she recounted these dates. She paused to wipe her face. "He only spoke a little French," she said, laughing at the memory of their awkward communication.

Aisha's parents also came from starkly different cultures. Her mother's ancestors were Songhai, among the intellectuals who helped create Timbuktu's scholarly tradition. Her father, a Fulani, descended from the fierce jihadis who seized power in the early 1800s and imposed sharia in Timbuktu. In Aisha's mind, her relationship with David continued a long tradition of mingling cultures. Many people pass through Timbuktu, she said. "Who is to say who Allah brings together?"

Two weeks after the couple met, David asked her to come to the United States. He wanted her to bring her two-year-old son from a previous relationship and start a life together. When her family heard the news, her uncle told David that since Aisha was Muslim, he would have to convert if he wanted to marry her. To his surprise, David agreed.

Three nights before Christmas, David left the Special Forces compound after curfew and met one of Aisha's brothers, who drove him through the dark, twisting streets to the home of an imam. Through an interpreter the imam instructed the American to kneel facing Mecca and recite the shahadah three times: "There is no God but Allah, and Muhammad is his prophet." He gave the soldier a Koran and instructed him to pray five times a day and to seek Allah's path for his life.

When David returned to the compound, his superiors were waiting for him. They confined him to quarters for violating security rules. Over the next week, he was not allowed to mix with the other Green Berets nor permitted to see Aisha, but he was able to smuggle out three letters. One begins: "My dearest [Aisha], Peace be upon you. I love you. I am a Muslim. I am very happy that I have been shown the road to Allah, and I wouldn't have done it without meeting you. I think Allah brought me here to you …" He continues: "I am not to leave the American house. But this does not matter. The Americans cannot keep me from Allah, nor stop my love for you. Allahu Akbar. I will return to the States on Friday."

Aisha never saw him again. He sent two emails from the United States. In the last message she received from him, he told her that the Army was sending him to Iraq and that he was afraid of what might happen. She continued to email him, but after a month or so her notes began bouncing back.

As she spoke, Aisha noticed tears had fallen onto the letters. She smoothed them into the paper and then carefully folded up the documents. She said she would continue to wait for David to send for her. "He lives in North Carolina," she said, and the way she pronounced North Carolina in French made me think she imagined it to be a distant and exotic land.

I tried to lighten her mood, teasing that she had better be careful or Abdel Kader Haidara would hear of her letters. After all, they are Timbuktu manuscripts, and he will want them for his library. She wiped her eyes once more. "If I can have David, he can have the letters."

Uncertain Endings

A month after I left Timbuktu, Mali officials, under pressure from the French government, freed four AQIM suspects in exchange for the Frenchman. The Italian couple was released, as were the Spanish aid workers after their government reportedly paid a large ransom. Since then AQIM has kidnapped six other French citizens. One was executed. At press time five remained in captivity somewhere in the desert. The marabout and his family disappeared from their home. Rumor spread that he had been recruited by the One-Eye to be his personal marabout.

I emailed David, who was serving in Iraq and is no longer in the Special Forces. He wrote back a few days later. "That time was extremely difficult for me, and it still haunts me." He added, "I haven't forgotten the people I met there, quite the contrary, I think of them often."

I called Aisha and told her that he was still alive. That was months ago. I haven't heard any more from David, but Aisha still calls, asking if there is any news. Sometimes her voice is drowned out by the rumble of the salt trucks; sometimes I hear children playing or the call to prayer. At times Aisha cries on the phone, but I have no answers for the girl from Timbuktu.