Air pollution kills millions every year, like a ‘pandemic in slow motion’

Dirty air is a plague on our health, causing 7 million deaths and many more preventable illnesses worldwide each year. But the solutions are clear.

This story appears in the April 2021 issue of National Geographic magazine.

When COVID-19 began tearing around the globe, Francesca Dominici suspected air pollution was increasing the death toll. It was the logical conclusion of everything scientists knew about dirty air and everything they were learning about the novel coronavirus. People in polluted places are more likely to have chronic illnesses, and such patients are the most vulnerable to COVID-19. What’s more, air pollution can weaken the immune system and inflame the airways, leaving the body less able to fight off a respiratory virus.

Many experts saw the possible connection, but Dominici, a biostatistics professor at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, was especially well equipped to test it. She and her colleagues have spent years creating an extraordinary data platform, one that aligns information on the health of tens of millions of Americans with a day-by-day summary of the air they’ve been breathing since 2000. Dominici explained it to me last summer on a video call from her home in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Her pandemic puppy, a black Lab, squirmed on her lap. In London, where I sat in my home office, the brief respite in traffic provided by the initial lockdown had ended, and diesel fumes once again clouded the air.

Every year, Dominici told me, she purchases granular (but anonymized) information on each of the roughly 60 million older Americans enrolled in Medicare—age, gender, race, zip code, and the dates and diagnostic codes for all deaths and hospitalizations. That’s half the data platform. The other half is an achievement in itself. Led by Dominici and Harvard epidemiologist Joel Schwartz, dozens of scientists first divided the United States into a grid of one-kilometer-wide (.62-mile) squares. Then they trained a machine learning program to calculate daily pollutant levels, over 17 years, in each square—even if it didn’t have a pollution monitor in it.

With those twin troves of data, Dominici and her colleagues could for the first time study the effects of air pollution in every corner of the U.S. It led them to some troubling conclusions. In a 2017 study they found that even in places where the air met national standards, pollution was linked to higher death rates. That means “the standard is not safe,” Dominici explained.

Two years later the team reported that hospitalizations for a host of ailments—including conditions such as kidney failure and septicemia, whose link to pollution had been little examined—went up whenever pollution rose. Those findings added to a mountain of evidence demonstrating the dangers of PM2.5, or particulate matter smaller than 2.5 micrometers, about a 30th the width of a human hair. Some of those particles—of soot, for example—can cross into the bloodstream. Scientists have found them, including even tinier “ultrafine” particles, in the heart, brain, and placenta.

When the pandemic hit, Dominici and her team quickly decided to cross-reference nationwide air quality data against Johns Hopkins University’s county-by-county tally of COVID-19 deaths. Sure enough, viral death rates were higher in places with more PM2.5—the places where decades of exposure to bad air had primed people’s bodies to be susceptible to the coronavirus. Worldwide, the team reported in December, particle pollution accounted for 15 percent of COVID-19 deaths. In badly polluted countries in East Asia, it was 27 percent.

Many outside the scientific world were shocked. The finding made headlines. “To me, it was not surprising at all,” Dominici said. “It made perfect sense.” She already knew what much of the public doesn’t—that dirty air ends far more lives, and with far greater regularity, than the novel coronavirus.

Globally, air pollution accounts for about seven million premature deaths a year, according to the World Health Organization (WHO)—more than twice as many as alcohol consumption and more than five times as many as traffic accidents. (Some recent research puts pollution’s toll far higher than the WHO estimate.) A majority of those deaths are caused by outdoor air pollution; the rest are attributable primarily to smoke from indoor cookstoves. Most of the deaths occur in developing countries—China and India alone account for about half—but air pollution remains a significant killer in developed ones too. The World Bank puts the global economic cost at more than five trillion dollars annually.

In the United States, 50 years after Congress passed the Clean Air Act, more than 45 percent of Americans still breathe unhealthy air, according to the American Lung Association. It still causes more than 60,000 premature deaths annually—not counting the many thousands who have died because it made them more vulnerable to COVID-19. Pollution is a hidden killer; it doesn’t get listed on death certificates. Perhaps this year, Dominici said when we spoke, its intersection with frightening new threats—a raging virus and wildfires—would help us recognize the damage it has been doing all along.

But in December, when the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency formally decided not to tighten the national air quality standards for PM2.5, maintaining them at their current levels, it ignored Dominici’s research and that of its own scientists. They had calculated that lowering the annual standard by 25 percent would save 12,000 lives a year.

Air pollution's brutal bottom line—the more there is, the shorter the lives of those who breathe it—was established most definitively by a landmark 1993 project known as the “Six Cities” study. People in the most polluted of six small American cities analyzed by Harvard researchers were 26 percent more likely to die prematurely than those in the cleanest of the six. Pollution was taking about two years off their life spans.

“It was very, very surprising. And in fact it was such a big effect, we didn’t believe it,” lead author Douglas Dockery, now retired, told me. But another long-term data set from the American Cancer Society soon confirmed it.

Since then, further research has revealed two more essential truths about air pollution: It’s harmful at much lower levels than once thought, and in many more ways. The sheer variety stunned Dean Schraufnagel, a pulmonary medicine professor at the University of Illinois at Chicago, when he led a panel in 2018 that reviewed and summarized decades of research.

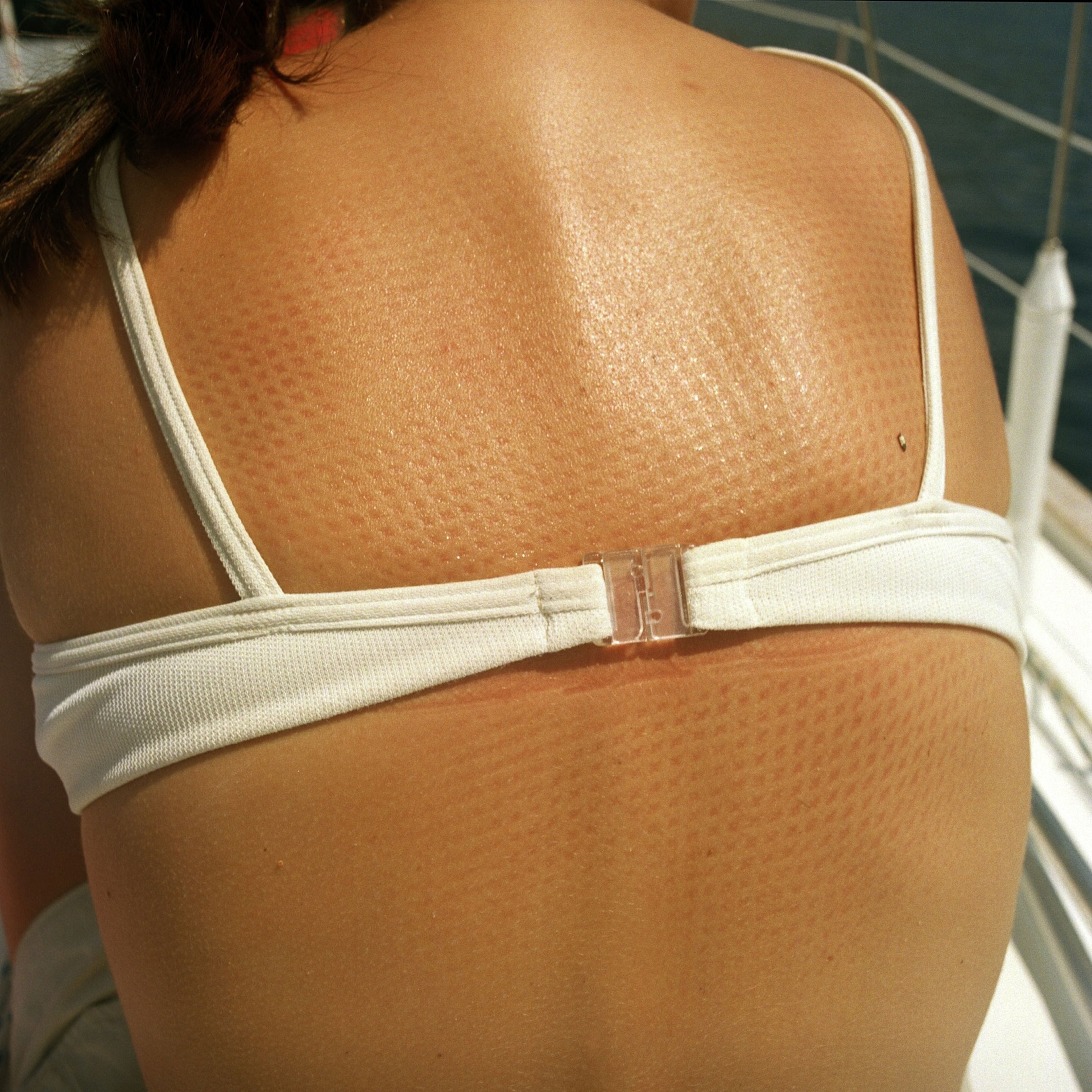

(See how pollution affects the human body)

Dirty air, his committee reported, affects nearly all the body’s essential systems. It may cause about 20 percent of all deaths from strokes and coronary artery disease, triggering heart attacks and arrhythmias, congestive heart failure and high blood pressure. It’s linked to lung, bladder, colon, kidney, and stomach cancers and to childhood leukemia. It harms kids’ cognitive development and raises older people’s risk of contracting dementia or dying of Parkinson’s disease. It’s been credibly tied to diabetes, obesity, osteoporosis, decreased fertility, miscarriage, mood disorders, sleep apnea—the list goes on.

“The breadth of it was the most surprising,” Schraufnagel said.

There’s a more hopeful flip side: Cleaner air brings better health. Since the Clean Air Act of 1970, a 77 percent drop in pollution has lengthened millions of Americans’ lives. The 1990 amendments to the law prevented 230,000 deaths in 2020 alone, according to an EPA estimate.

Elsewhere in the world, the air is far worse. Photographer Matthieu Paley and I visited Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia, one of the most polluted capitals on Earth—especially in the punishing winter, when coal becomes a survival tool. It’s burned by the ton in the city’s power plants and by the bagful in the gers (Mongolian yurts) that house poor migrants from the countryside.

“I no longer know what a healthy lung sounds like,” said Ganjargal Demberel, a doctor who makes house calls in one such neighborhood. “Everybody has bronchitis or some other problem, especially during winter.”

Even environmentally progressive Europeans live with pollution significantly worse than what Americans endure. In eastern and central Europe, health- and climate-wrecking coal smoke still pours from home chimneys and power plants. In London, where I’ve lived for 20 years, coal smoke once blanketed the city in deadly pea soup fogs, but mercifully, those days ended long before I arrived. Instead, the country and its continental neighbors now suffer the effects of another toxic fuel: diesel.

Dirtier than gasoline, diesel’s long been popular in Europe because it offers vehicles slightly better mileage. Paris and Barcelona, Rome and Frankfurt—their busy thoroughfares are clouded with fumes like London’s, air so thick it covers your teeth with a layer of grit. I feel the difference every time I return to New York and gulp air noticeably cleaner than London’s. Back in Britain, I worry what the fumes may be doing to my teenage daughter, whose lungs are still growing and vulnerable.

The root of Europe’s air quality problem is not just a particular fuel but also the political and regulatory failures that let auto manufacturers get away with selling cars whose emissions shattered legal limits. In 2015 the public learned that Volkswagen had programmed 11 million diesel cars with “defeat devices”—software that activated pollution controls during tests but turned them off the rest of the time. U.S. authorities forced the company to spend billions compensating customers and fixing or buying back vehicles. Europe, however, has allowed 51 million cars and vans (from a variety of manufacturers) to stay on the road with nitrogen dioxide emissions three or more times the limit, according to the advocacy group Transport & Environment. That excess pollution causes nearly 7,000 premature deaths annually, one study found.

Instead of forcing manufacturers to bring cars into compliance, Europe is mostly leaving cities to tackle the problem. Across the continent, local governments are banning the dirtiest vehicles or penalizing their owners. It’s one step toward cleaner air—and there are signs that such measures are pushing drivers away from diesel—but the patchwork efforts aren’t nearly as effective as higher-level action could be.

Diesel and coal aren’t the only things fouling the air, of course, in Europe or elsewhere. Woodsmoke from fireplaces or stoves, thick with PM2.5, is a growing problem. Last year’s lockdowns gave scientists an unexpected chance to see what happens when some sources of pollution temporarily cease. As the virus ravaged northern Italy in the spring, Valentina Bosetti and Massimo Tavoni, married economists at the RFF-CMCC European Institute on Economics and the Environment in Milan, were stuck at home with their three sons.

“Instead of killing each other and killing the kids, at some point we thought, OK, there is this data,” Bosetti told me.

Despite transportation and industry being all but halted, the couple found that air quality hadn’t improved as much as many locals thought. “Newspapers were saying, Blue sky, everything is perfect,” Bosetti said. “Not really.” At monitors away from roads or factories, PM2.5 levels fell only 16 percent, nitrogen dioxide only 33 percent. One big sector, it turned out, was still polluting while people stayed home: agriculture.

Modern industrial farming is a major polluter. One study ranked agriculture as the biggest single PM2.5 source in Europe, the eastern U.S., Russia, and East Asia. Huge amounts of manure, as well as chemical fertilizers, give off ammonia, which reacts with other pollutants in the air to create the tiny particles. Scientists have long understood that, but Bosetti hopes the vivid real-world demonstration may help generate political will to take action.

China still leads the world in air pollution deaths, but it has made great strides lately in cleaning its skies—whereas India’s response has been mostly ineffectual. Indian cities hold nine of the top 10 spots in the WHO database of PM2.5 levels. The human cost is horrific: nearly 1.7 million premature deaths a year.

India’s pollution floats from a dizzying variety of sources. Trash fires smolder in streets where garbage goes uncollected. Frequent power outages mean diesel generators are common. Villagers and the urban homeless burn wood, dung, and even plastic to cook and keep warm. Every autumn, clouds of smoke drift over Delhi from Punjab and Haryana, where farmers set fields alight to clear them after harvest.

“It’s like living in a gas chamber,” Delhi writer and activist Jyoti Pande Lavakare told me. In the worst months, whenever she goes outside, “I get a dull pollution headache. My daughter gets a headache too; she feels a little nauseous sometimes. Your eyes will water.” Americans got a brief taste of Delhi’s typical pollution last fall, when parts of the West were engulfed by wildfire smoke.

Lavakare used to live in California, but in 2009 she and her husband moved their family home to be near their parents. She was surprised by how much worse India’s pollution had gotten. Her parents shrugged off her suggestion to install air purifiers but felt better after she bought some. Then, in 2017, her mother was diagnosed with lung cancer.

“It moved so fast,” Lavakare recalled. The doctors “were like, Yeah, see where she lives? She’s lived in north India all her life. This is the pollution capital of the world.” She died in 2018.

By then Lavakare had co-founded an advocacy group that fought successfully for parliament to debate the issue—and even filed a human rights petition with the United Nations. She wrote a book, Breathing Here Is Injurious to Your Health, about her mother’s death. “There’s nothing we haven’t tried,” she told me. “Sadly, I don’t think we’re making much progress.”

For a time in the 1990s and early 2000s, things looked hopeful in Delhi. Pushed by the Supreme Court, the city demanded that buses and its ubiquitous auto-rickshaws switch to running on compressed natural gas. But economic growth quickly outpaced all antipollution measures. The number of cars on India’s roads, for example, more than quadrupled from 2001 to 2017. Brickmaking intensified to feed the construction boom—and the bricks were made in kilns that burned coal without filtering the smoke.

There has been one bright spot: A push to give rural Indians alternatives to smoky cooking fuels has cut indoor pollution and saved hundreds of thousands of lives a year. But there’s been no significant improvement in outdoor pollution for a decade, said Sarath Guttikunda, director of Urban Emissions, a research group. “We have not seen a decline of any sort in any of the cities,” he told me.

Lavakare now regrets giving up her American green card. She knows her position is privileged: India’s urban poor, who work or even live on the streets, breathe far worse air. It’s a dynamic seen all over the world. Like the coronavirus, pollution maps onto the existing fractures in our societies. But with COVID-19, deaths “happen right away. With air pollution, it just adds on over time,” Lavakare said. “It’s a pandemic in slow motion.”

In the U.S., pollution adds one more dimension to the nation’s stark racial inequality. Black Americans, one study found, are exposed to about 1.5 times more PM2.5 than the overall population—and the disparity is more racial than economic.

“Rich Black Americans breathe more pollution than poor white Americans, consistently,” Dominici told me. The divide is growing. “As we’ve been cleaning up the air in this country, we’re cleaning the air mostly where whites live.”

Resistance from those who suffer under that disparity is growing. In 2013, when Shashawnda Campbell was still in high school in south Baltimore, she heard that Maryland had approved plans for a new incinerator less than a mile from her school. Her reaction was immediate: “No. We don’t need that. It already stinks here; it’s already polluted enough.”

The Brooklyn and Curtis Bay neighborhoods, where Campbell and her classmates lived, are poor, with sizable Black and Latino populations. The area was already burdened with a medical waste incinerator, a chemical plant, a landfill, and an enormous open coal pile. “It’s not by accident that all these things are in this community. This is on purpose,” Campbell said. A dirty facility gets put in Brooklyn or Curtis Bay “because no one else wants it. But they don’t ask us if we want it.”

People of color are often consigned to industrial neighborhoods by a legacy of racist mortgage restrictions. And companies build new polluting facilities in such areas because land is cheaper and residents tend to have little political sway, said George Thurston, an environmental medicine professor at New York University. “They avoid the wealthier neighborhoods where people have that power,” he said. “They want to locate in places where there’s less resistance.”

Campbell wasn’t ready to let that happen again. Calling themselves Free Your Voice, she and a group of classmates started knocking on doors and gathering signatures. “We knew we had to fight back,” she recalled. It took three years, but they won. The incinerator plans were halted. “It was just so amazing to see that wow, we really did something. We made a change.”

These days, Campbell goes into schools to teach kids how to combat environmental racism. At her old high school, a coach told her he couldn’t field a basketball team, “because all of them have asthma. They can’t run long enough.” Last summer, at Black Lives Matter marches, fellow protesters told her it had never occurred to them to connect pollution and police violence. “They’re all racism in different forms,” she said.

(See maps showing how areas of the world burn each year)

On the other side of the continent, Anthony Victoria’s opponent isn’t a single incinerator but the consumer economy—at least in its current form. Victoria, a young man with a goatee and round glasses, lives in California’s Inland Empire, a region once known for its citrus groves. Sixty miles inland from the container ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach, it’s now a warehouse hub—for Amazon, Target, Walmart—distributing products imported from China and elsewhere. “You just see row after row after row, warehouse after warehouse after warehouse,” Victoria said. “You have a residential neighborhood, and you have a huge mega warehouse across the street.”

The real problem is the relentless stream of trucks that rumble through neighborhoods filled with working-class people of color and immigrants. “It’s the slow violence of the supply chain that really sucks the energy and the health and the livelihoods” of the communities, Victoria told me. The Center for Community Action and Environmental Justice, an advocacy group he then worked for, gave residents handheld counters to log truck traffic. Along State Route 60, an east-west freeway, they counted 1,161 in an hour.

“You can imagine the negative effects that’s going to have on someone’s life,” Victoria went on. “Our communities are known as diesel death zones.” Recently, COVID-19 has torn through some of the warehouses. “You have people that are just completely, completely in fear,” Victoria said—warehouse workers “already immunocompromised because of the pollution,” and now terrified they’ll bring the virus home to children and parents with asthma or cancer.

Here too, there are hints of change. Victoria’s group shared its truck counts with the California Air Resources Board, whose rules often lead the nation. Last year, the agency issued a new one: Manufacturers must begin phasing in zero-emissions trucks in the state by 2024, with the share of new trucks that are pollution free increasing steadily until 2035. The agency also is expanding a requirement that ships shut off their engines and plug into onshore power while docked, or else use pollution-capturing technology. Together, the truck and ship rules “are going to make a huge difference,” said Joe Lyou, president of the California-based Coalition for Clean Air.

Like many measures that reduce unhealthy air pollution, the new rules also cut climate-warming carbon emissions. Both share the same cause: our dependence on fossil fuels. And that means a shift toward cleaner energy, away from oil, gas, and coal, is urgent not only for heading off a frightening future of droughts, floods, wildfires, and storms. It also will make us healthier now—with the most affected communities likely to reap the biggest gains. Just switching to electric vehicles could save thousands of lives and $72 billion in health damage annually in the U.S., according to the American Lung Association.

Victoria sees hope in that. He believes industries like electric truck manufacturing can bring his community new economic opportunities along with cleaner air. “We don’t necessarily have to sacrifice our quality of health or our air quality for a job,” he said. “We can have both.”

(What the Clean Air Act did for Los Angeles—and the country)

Climate change and air pollution have the same cause and the same solution, but they play out on different time scales. One of the most striking things about air pollution is how quickly health improves when it clears. The economic shutdowns triggered by COVID-19 last year temporarily slowed the world’s carbon emissions, but the total amount of carbon in the atmosphere continued to rise, and the long-term threat from climate change got that much worse. In contrast, every incremental and local decline in pollutants such as PM2.5 or nitrogen dioxide translates immediately into fewer asthma attacks, heart attacks, and deaths.

In China, researchers drew a stunning conclusion: Improved air quality during the lockdown in early 2020 saved upwards of 9,000 lives, according to one study, and roughly 24,000, according to another—more lives than the virus took, in any case, at least according to China’s official statistics, which put the COVID-19 toll below 5,000. Scientists have long understood that better air saves lives, said Yale epidemiologist Kai Chen, lead author of the first study. But “it’s just so dramatic” to see it happen.

While the pandemic’s deadly impact has been impossible to ignore, pollution gets far less attention, though it kills far more people. One reason, Dominici suggested, is that it’s so hard to link pollution to individual deaths—to attach names and faces to the victims. One person who has managed to change that is Rosamund Adoo Kissi-Debrah, Britain’s best known clean-air activist. Living in London, I’ve gotten to know her a bit. We met again on a sunny day last summer for a socially distanced chat, in a park bursting with wildflowers.

Kissi-Debrah’s eldest daughter, Ella, died from asthma at age nine in 2013. The family lives less than a hundred feet from one of London’s busiest roads, the South Circular, and Kissi-Debrah now believes its exhaust fumes were what sickened Ella. She’s spent years waging a legal battle to prove it. A teacher before grief upended her life, she has turned tragedy into a teachable moment by getting pollution officially added to Ella’s death certificate as a contributing factor.

After Ella’s death, Stephen Holgate, a University of Southampton asthma specialist, found that many of the child’s dozens of hospitalizations, including the final one, had coincided with pollution spikes. With cleaner air, he concluded, Ella might well be alive. As a parent, “that’s quite hard to take,” Kissi-Debrah told me. Three silver hearts hung from a chain around her neck, engraved with the fingerprints of Ella and two younger children.

Ella was active and energetic before she got sick, and even between bouts of asthma, Kissi-Debrah recalled. “Everything came easily to her”—reading, music, swimming. Ella’s attacks were so bad they sometimes triggered seizures. But as soon as she felt better, “she wanted to get on her skateboard. She was a real tomboy.”

At the first inquest in 2014, the coroner decided Ella had died of acute respiratory failure and asthma, without considering any external cause. Kissi-Debrah pressed on, and her fight drew wide media coverage. Getting pollution written onto Ella’s death certificate, she believed—a British and perhaps a world first—might be cold comfort for her, but it would have moral and political power. A legal judgment that Britain’s air helped end the life of one child would unmistakably imply that it endangers others—and that something should be done.

Kissi-Debrah knows the answers aren’t complicated. Tough, science-based regulations work, if governments enforce them. “My daughter wasn’t the only one,” she said. For the rest of London’s kids, “I want real change.” I thought of my own daughter, growing up in the fumes.

Last December, with the second inquest finally under way, Holgate compared Ella to “a canary in a coal mine.” He testified that she had been through more than two years of regular “near-death experiences” before succumbing. In the end, the coroner ruled that air pollution—which was beyond British legal limits near Ella’s home—had indeed contributed to her death. For once, the seven million lives lost each year to dirty air were represented by a face. It belonged to a beautiful young girl.

Beth Gardiner is the author of Choked: Life and Breath in the Age of Air Pollution. Photographer Matthieu Paley has shot multiple stories for the magazine in India and Central Asia.