An urgent question hangs over catastrophic wildfires: What’s in that toxic smoke?

Scientists are rushing to learn more about those dangerous swirls of gases and particulate matter—and how they threaten our health.

This story appears in the April 2021 issue of National Geographic magazine.

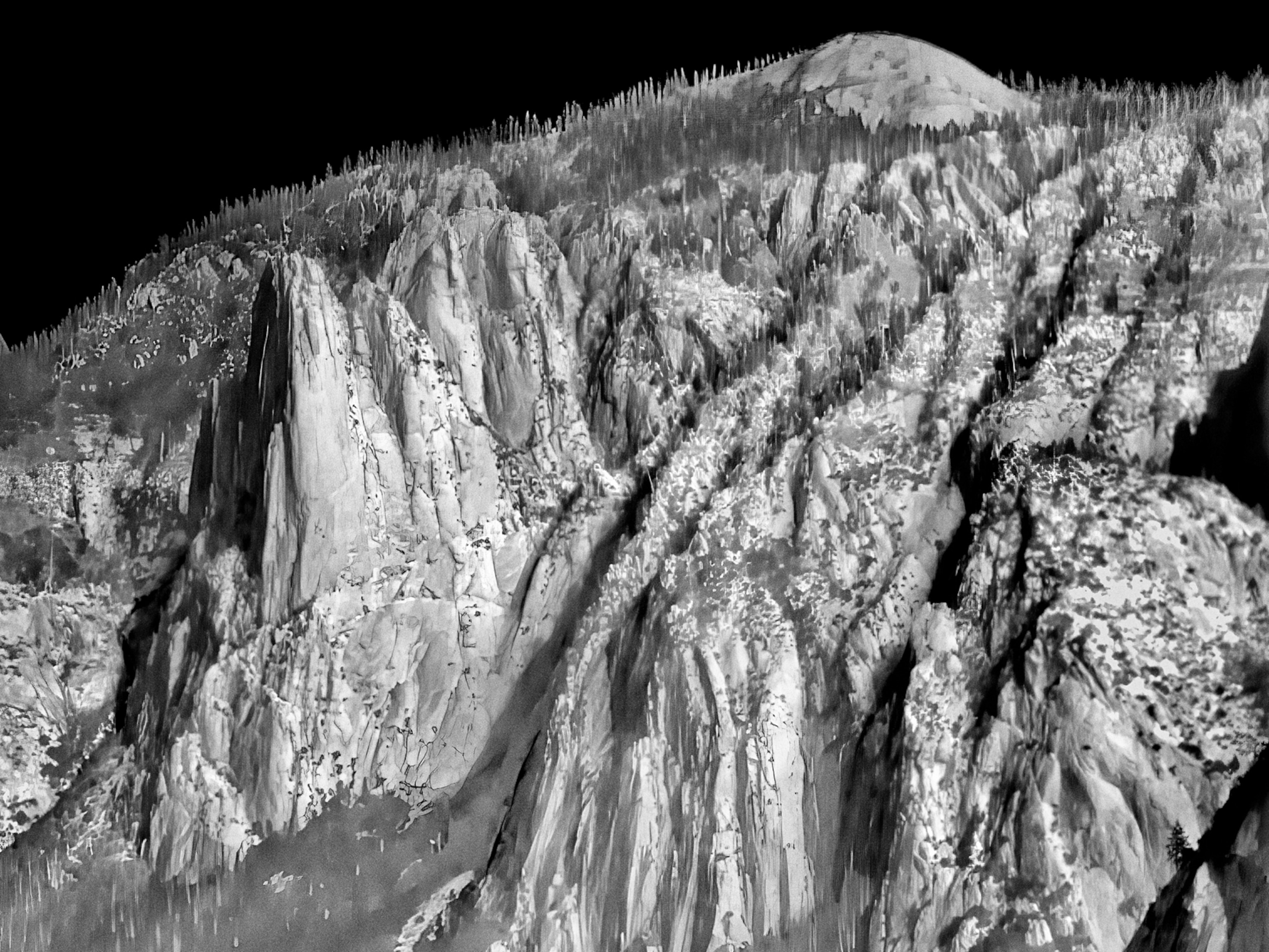

On a rural highway in Northern California, a July traveler’s tire went flat. Metal rim scraped against pavement. The sparks ignited a fire that ripped through dry forest, whirled into flame tornadoes, and roared over tens of thousands of acres, making fuel of everything in its path. When it jumped the Sacramento River and headed for the city of Redding, Keith Bein prepped his new rig—a trailer holding two tiny electric cars, a lot of tubes and instrumentation, and a white contraption that looks like a miniature lighthouse.

Bein works as an atmospheric scientist at the University of California, Davis campus, about 150 miles south of Redding. By the time he hooked the loaded trailer to his truck and began driving upstate, the 2018 Carr Fire—those sparks ignited near a power plant called Carr—was already one of the biggest wildfires in California history. It had killed six people, including two firefighters. It was burning trees, grasslands, mountain cabins, pedestrian bridges, light posts, fences, parked cars. At the Redding outskirts it had just burned a suburb called Lake Keswick Estates, which meant the full infrastructure of single-family housing: insulation, shingles, refrigerators, paint.

And everywhere around the Carr Fire’s great trajectory was smoke—billowing, blanketing, spreading thousands of miles beyond the actual flames. Of all the things that foul the air we breathe, it’s wildfire smoke that most fascinates Bein.

He wants to understand exactly what’s in it, how its chemistry differs from one fire to the next, and what this century’s unprecedented megafires mean for global air pollution and human health. In western North America and in Australia, as measured by the size and number of wildland fires, 2018 was the worst year in recorded history—until 2020 eclipsed it.

“An event like this used to happen, like, once in your lifetime—where your personal life was impacted by a huge wildfire,” Bein says. “Now it’s happening every summer. That’s a major public health concern.”

So there he was at Lake Keswick Estates, the ground charred, the residents evacuated, whole blocks of houses leveled to their smoldering foundations. He braced the trailer and powered up the contraption, which is actually a sophisticated air pump and sensor. He pulled tubing and monitors from the electric cars, which provide mobile rechargeable power for the whole setup. His eyes and nose hurt. Imagine yourself by a campfire, Bein says, when the wind shifts and shoves smoke directly into your face. “Absolutely horrible,” he says.

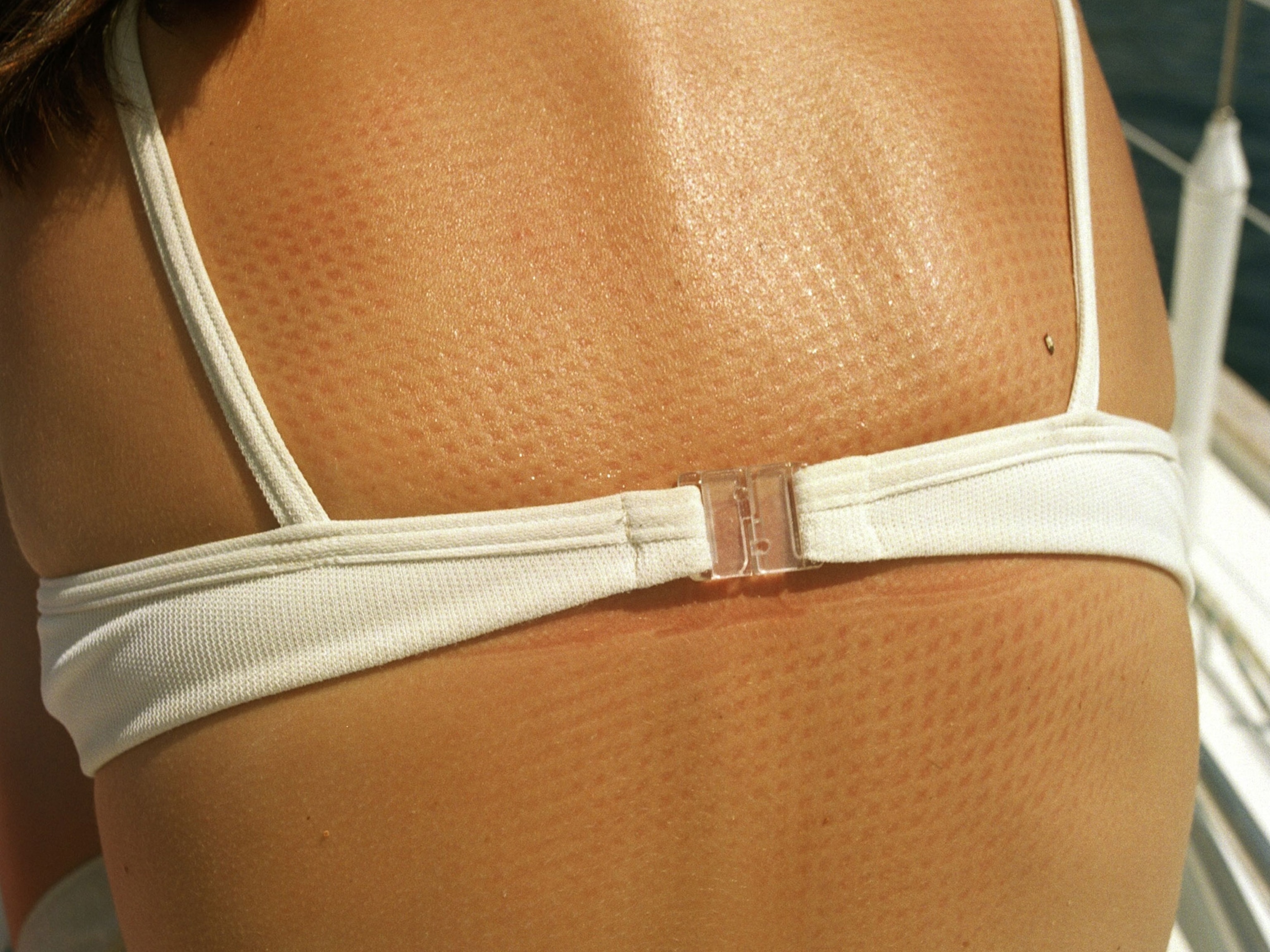

But perfect for his work. Although the flames had moved on, Bein and other researchers know smoldering produces its own intensely toxic smoke. They know the construction of so many residences amid and alongside wildland areas has created communities that are affordable and scenic—and vulnerable, as the warming climate parches forests into tinder. Wildland-urban interface, they call such places, or WUI (which in wildfire parlance is pronounced like a cry of astonishment, woo-eee). They know giant WUI fires make giant WUI smoke: burning-landscape plus burning-building pollution, roiling together into one noxious mix.

(A world ablaze: These maps show the devastating paths of wildfires)

What's actually in that mix? And what happens to humans and other animals breathing emissions from such huge conflagrations? These questions are an increasingly urgent part of the effort to understand and reduce air pollution, and the answers are more elusive than you might imagine. Think about what it takes to bring real wildfire smoke into a research facility. You need to become the equivalent of a tornado chaser, explaining your way through police barricades, as Bein does when the situation calls for it. Or you rig up a C-130 cargo plane with smoke-sucking fuselage tubes and fly straight into wildfire plumes, like the research team that spent the summer of 2018 making sorties over fires in Colorado and Idaho.

“We turn the airplane into a flying chemistry lab,” says Colorado State University atmospheric scientist Emily Fischer, who leads the researchers analyzing what they found in the smoke. The ingredients include carbon monoxide, hydrogen cyanide, and more than a hundred other gases, as well as the dangerous fine particles (PM2.5) Beth Gardiner describes in her story. There’s no dispute about the most immediate health hazard: Wildfires pollute, whether the smoke is WUI or “natural,” and just a few days of enough exposure to their smoke can send people with asthma or other sensitivities to emergency rooms.

It’s also possible—the evidence is “inconclusive,” as scientists say—that breathing a wildfire’s smoke kicks off the kind of cellular changes that could lead to later health calamities: heart failure, lung disease, stroke. Questions have arisen about Alzheimer’s disease too. Just figuring out how best to explore these links has been an extraordinary challenge for researchers; you can’t start a true wildfire for experimental purposes. They have to take into account the physical and emotional stress any wildfire can set off, even for people not in the path of the flames. And the smoke itself keeps changing during a fire, no matter what’s being burned, as its components heat and cool and interact. “The chemistry of each burn can result in different health outcomes,” says Lisa Miller, a respiratory immunologist at the California National Primate Research Center. “This is going to take us a while to sort out.”

About 4,000 monkeys live at the primate center, many in outdoor enclosures, and it was a smoke-bleak day during the state’s bad 2008 wildfires that gave Miller the idea to start a multiyear study of the newest group of rhesus babies—who were spending their first weeks of life breathing wildfire smoke. Moving the newborns inside for protection wasn’t an option, Miller says; that would have disrupted social groupings, as there’s not enough indoor housing for all the animals. Her team and the center’s veterinarians have kept close watch on the group exposed as infants, and now at 12 years old—the rhesus equivalent of human millennials—the monkeys aren’t showing health problems serious enough to warrant treatment. But there are troubling signs. When their blood samples are exposed to infection in the lab, the immune responses are sluggish. And compared to rhesus babies born in 2009, a year with cleaner air, the monkeys who breathed heavy smoke during their first weeks of life have smaller lungs and airways that appear impaired. The parallels for humans are worrisome. “Usually you’re not diagnosed with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or fibrosis until you’re in your late 50s or early 60s,” Miller says. “So we think what we’re seeing is perhaps the early stages of a chronic lung condition.”

It bears remembering that most of the world’s air pollution still comes from other sources: tailpipes, furnaces, industrial plants, foliage-clearing agricultural burns, indoor cooking fires. But wildfires are multiplying and enlarging so rapidly that we have new vocabulary for them. Megafire lacks formal definition, but it’s generally used to mean at least 100,000 acres of burning terrain. A few years ago, when the online journal Wildfire Today asked its audience to suggest names for even bigger conflagrations, a reader came up with one at once. You may have seen it in headlines last summer: Gigafire.

(What the Clean Air Act did for Los Angeles—and the country)

Megafires wreck far more than the air we breathe, of course, and the proposals for what to do about them are by turns daunting, expensive, and counterintuitive. Daunting: Stop global warming, which is heating wildlands, drying foliage, killing trees, and producing weird weather like the 14,000 lightning strikes in 2020 that started California’s August Complex gigafire—more than a million acres. “We’re using terms like ‘mega’ and ‘giga,’ but it’s really just the beginning,” says University of Tasmania epidemiologist Fay Johnston, one of the world’s leading wildfire smoke researchers. “If we don’t do anything about climate change, we ain’t seen nothing yet.”

Expensive: Thin wildlands aggressively, hauling away dead trees and other dried-out debris that built up because we’ve spent so many years reflexively putting out wildfires. This is a huge task. It would cost a great deal for machinery and labor.

Counterintuitive: Use fire. Let more small wildfires burn when they aren’t endangering homes; that’s nature’s way of clearing the debris and encouraging new growth. Indigenous people understood prudently contained flames as a land management tool, and nearly every megafires proposal includes a plea for more prescribed fires—planned, that is, with careful consideration of wind and the impact on people living nearby. Yes, these smaller fires make smoke too. But not as much. Says Donald Schweizer, a University of California, Merced air quality researcher: “There really is no ‘no smoke’ option.”

Even in regions where clean air regulations have lowered other forms of air pollution, air purifiers and personal air quality monitors, like the new apps that let you check smoke contamination levels wherever you happen to be, are a grim growth industry. Bein brought his first purifier into his family’s Oakland home during 2017’s terrible fires; now they own six. “It’s not a matter of if,” he says. “It will happen again.”

At his UC Davis lab, Bein says, nearly everything shut down early last year for the pandemic as he and his team were well into what he calls “the first layer” of pulling chemical and toxicological information from his Carr Fire smoke samples. He and his co-workers were determined to continue collecting, so even though the rig was grounded, they set up a sampling site on the roof of a university building. A graduate student kept climbing up to collect and replace the filters on the air pump, and by winter, when the historic 2020 fires finally stopped, Bein had a collection of more than six dozen sheets of scientific-grade filter paper, each loaded with evidence and wrapped in wax paper for protection. “I’ve already had a lot of requests for these samples,” Bein says. He’s storing them in a freezer, for now, at 80°C below zero.

Contributing writer Cynthia Gorney lives in California and recently bought a home air purifier. Stuart Palley is a trained wildland firefighter and has documented more than a hundred California fires.