Insect Eggs

Engineered for survival, insect eggs hang on and hatch wherever their parents deposit them.

We fool ourselves most days. We imagine the Earth to be ours, but it belongs to them. We have barely begun to count their kinds. New forms turn up in Manhattan, in backyards, nearly anytime we flip a log. No two seem the same. They would be like extraterrestrials among us, except that from any distance we are the ones who are unusual, alien to their more common ways of life.

As the vertebrate monsters have waxed and waned, the insects have gone on mating and hatching and, as they do, populating every swamp, tree, and patch of soil. We talk about the age of dinosaurs or the age of mammals, but since the first animal climbed onto land, every age has been, by any reasonable measure, the age of insects too. The Earth is salted with their kind.

We know, in part, what makes the insects different. Those other first animals tended to their young, as do most of their descendants, such as birds, reptiles, and mammals, which still bring their young food and fight to protect them. Insects, by and large, abandoned these ancient traditions for a more modern life.

Insects evolved hardened eggs and with them a special appendage, an ovipositor, which some use to sink their eggs into the tissue of Earth. Lift a stone and you will find them. Split a piece of wood, and they are there, but not only there. Birds struggle to find good places to nest, yet insects evolved the ability to make anything—wood, leaves, dirt, water, even bodies (especially bodies)—a nursery. If there is a single feature that has ensured insects' diversity and success, it is the fact that they can abandon their young nearly everywhere and yet have them survive—because of those eggs.

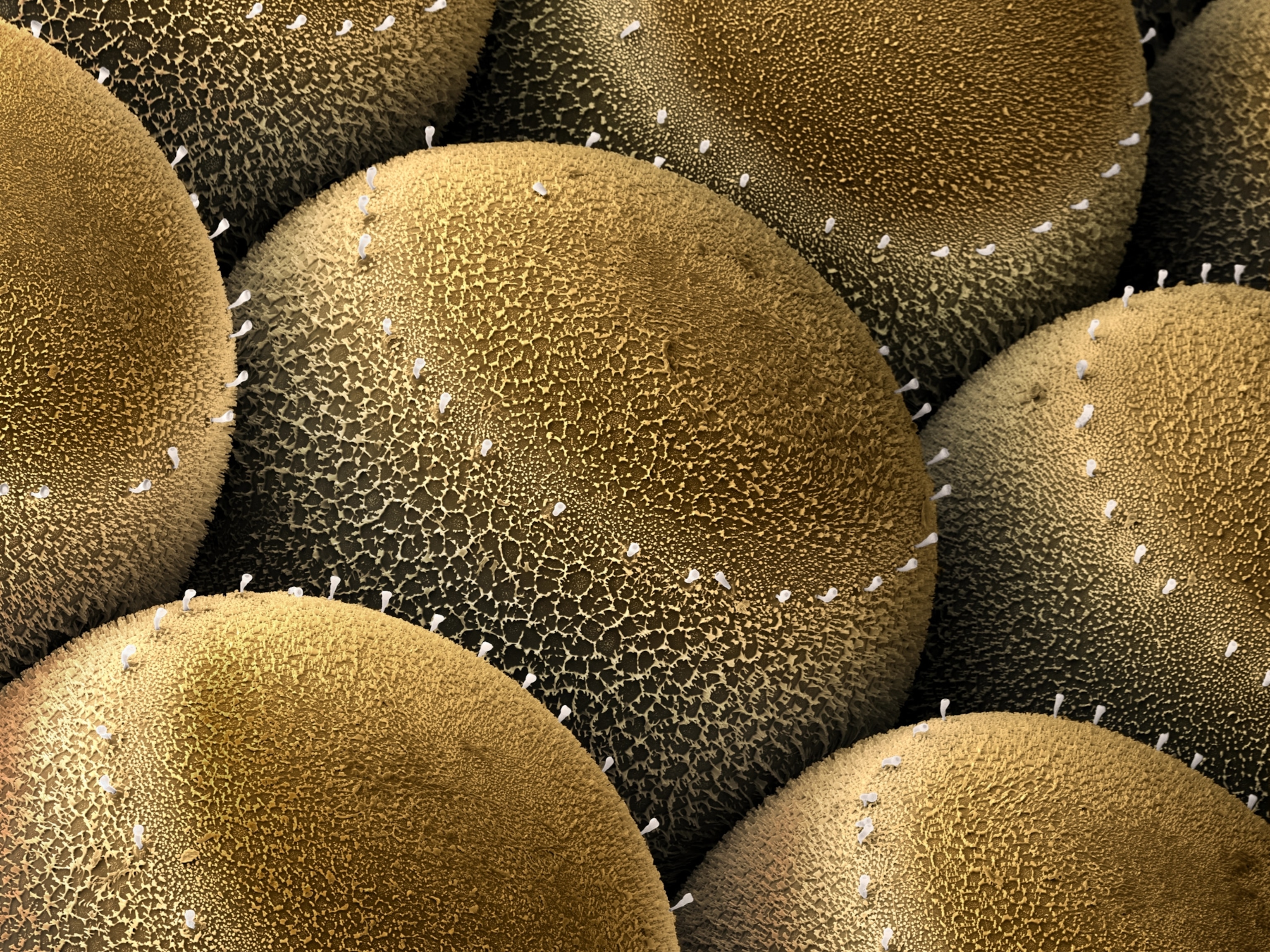

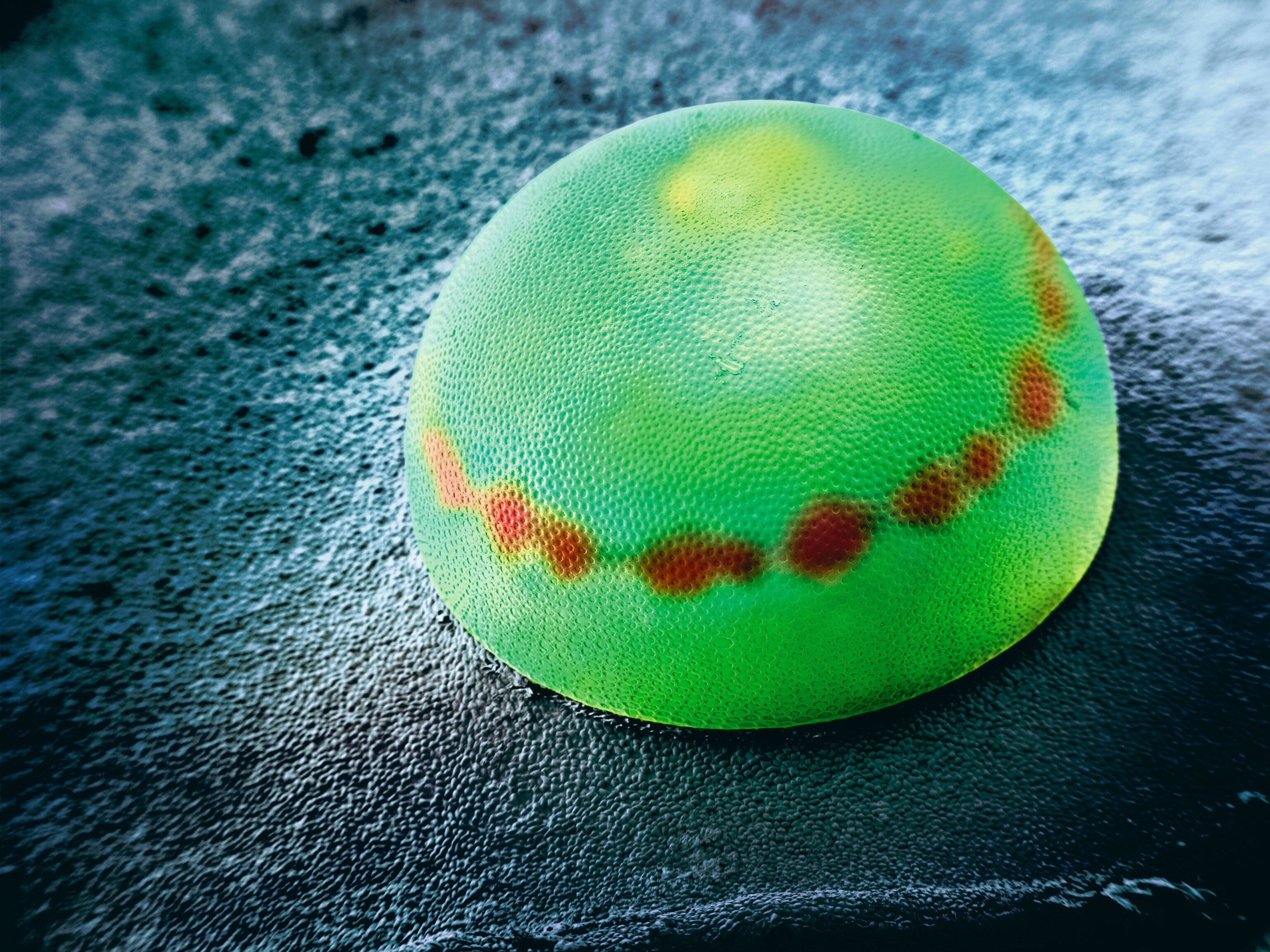

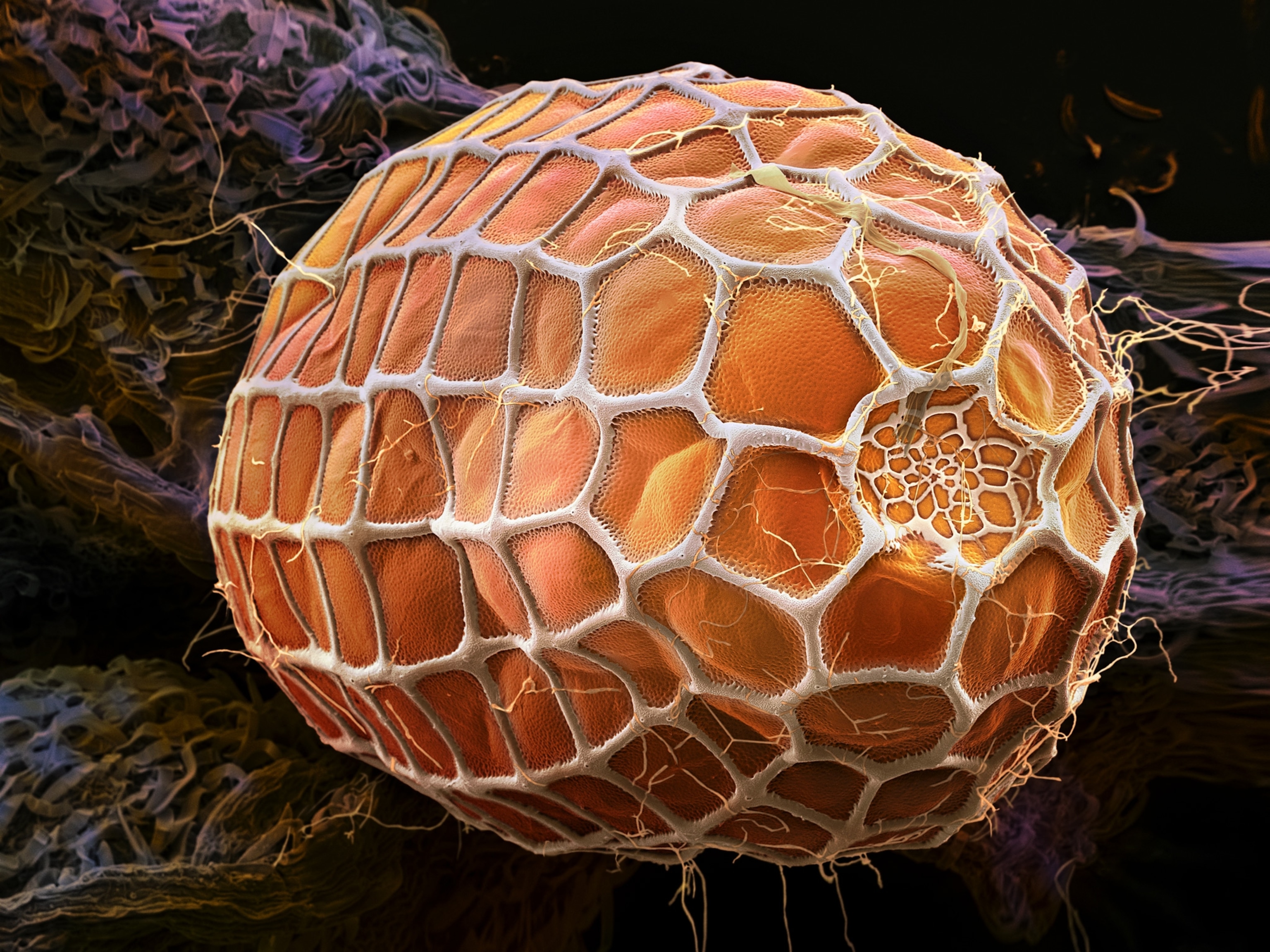

They began simply, smooth and round, but over 300 million years, insect eggs have become as varied as the places where insects reign. Some eggs resemble dirt. Others resemble plants. When you find them, you might not know what you are seeing at first. The forms are unusual and embellished with ornaments and apparatuses. Some eggs breathe through long tubes that they extend up through water. Others dangle from silky stalks. Still others drift in the wind or ride on the backs of flies. They are as colorful as stones, shaded in turquoises, slates, and ambers. Spines are common, as are spots, helices, and stripes. More than biology, their designs suggest the work of an artist left to obsess among tiny forms. They are natural selection's trillion masterpieces; inside each is an animal waiting for some cue to break free.

The basic workings of insect eggs, however, like the basics of any egg, are recognizable. The egg develops its shell while still inside the mother. There the sperm must find and swim through an opening at one end of the egg, the micropyle. Sperm wait inside the mother for this chance, sometimes for years. One successful sperm, wearied but victorious, fertilizes each egg, and this union produces the undifferentiated beginnings of an animal nestled inside a womblike membrane. Here eyes, antennae, mouth parts, and all the rest form. As they do, the creature respires using the egg's aeropyles, through which oxygen diffuses in and carbon dioxide out. That all of this occurs in a structure typically no larger than a grain of raw sugar is simultaneously beyond belief and ordinary. This is, after all, the way in which most animals ever to have lived on Earth had their start.

What you see in the accompanying photo gallery are the eggs of a few small branches of the insect tree of life. Among them are those of some butterflies that face extraordinary travails to defend themselves against predators and, sometimes, against plants on which they are laid. Some passionflowers transform parts of their leaves into shapes that resemble butterfly eggs; mother butterflies, seeing the "eggs," move on to other plants to deposit their babies. Such mimics are imperfect, but fortunately so is butterfly vision.

Eggs must also somehow escape having the eggs of another type of insect, parasitoids, laid inside of them. Parasitoid wasps and flies use their long ovipositors to thrust their eggs into the eggs and bodies of other insects. Roughly 10 percent of all insect species are parasitoids. It is a well-rewarded lifestyle, punished only by the existence of hyperparasitoids, which lay their eggs inside the bodies of parasitoids while they are inside the bodies or eggs of their own hosts. Many butterfly eggs and caterpillars eventually turn into wasps as a consequence of this theater of life. Even the dead and preserved eggs shown here are likely to hold mysteries. Inside some are young butterflies, but inside others may be wasps or flies that have already eaten their first supper and, of course, their last.

Every so often, and against all odds, a group of insects has regressed a little and decided to care more actively for its young. Here and there we see the evidence. Dung beetles roll dung balls for their babies. Carrion beetles roll bodies. And then there are the roaches, some of which carry their newborn nymphs on their backs. The eggs of these insects have become featureless and round again, like lizard eggs, and in so doing also become more vulnerable and in need of care, like our own young. Yet they survive. Perhaps they are the vanguard of what will come next, the next kingdom beginning to rise. Though perhaps not. Recently I watched a dung beetle rolling a ball, and the ball looked like a rising sun. Above that beetle was a fly trying to lay an egg inside the beetle's head.

Insects have been cracking out of eggs for hundreds of millions of years. It is happening now, all around you. If you listen, you can almost hear the crumbling of the shells as tiny feet, six at a time, push into the world.