6 memorials built by women—and the love stories behind them

One was a wonder of the ancient world; another inspired the Taj Mahal. The stories behind these monuments have stood the test of time.

While many fine buildings were famously constructed by men to celebrate their beloveds—from India’s Taj Mahal to Italy’s Torrechiara Castle—there are few such tributes commissioned by women. Those that do exist were built by women who had to buck tradition or challenge societal norms.

In order to honor their darlings with temples, tombs, sculptures, and stepwells, they broke royal customs, protested equality laws, or shifted architectural trends. Here are six sites around the world where women have dared to memorialize their love.

The Royal Mausoleum at Frogmore, England

When Queen Victoria’s 42-year-old husband, Prince Albert, died suddenly from illness in 1861, the queen was inconsolable.

“She spent the rest of her life honoring his memory—draping herself and her court in black, withdrawing from public and social engagements, and surrounding herself with images of her late husband,” says British historian Tracy Borman, author of Crown & Sceptre: A New History of the British Monarchy. “The grieving queen also sought solace by commissioning statues and memorials in his memory.”

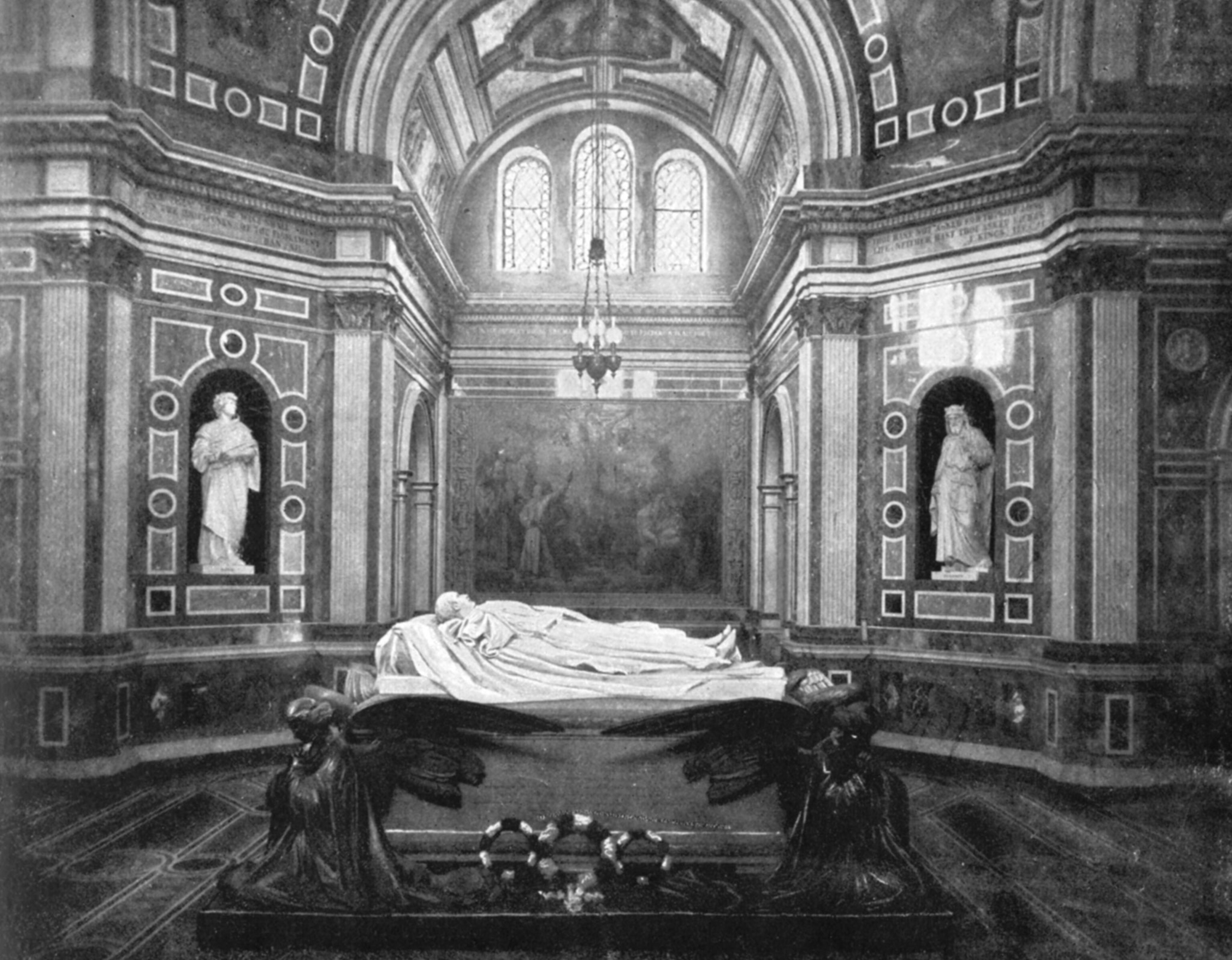

Soon after Albert’s death, the queen began work on a mausoleum at Frogmore, a royal estate near Windsor Castle, which wasn’t completed until 1871. Albert was laid to rest here and she was buried next to him in 1901, a departure from the royal tradition of being interred at Westminster Abbey or St. George’s Chapel in Windsor.

Tourists cannot enter the tomb. But they can view the stately building from the manicured grounds of adjacent Frogmore House, which will reopen to the public later this year. If they could see inside, they’d find a colorful interior inspired by Albert’s passion for Italian Renaissance art and, as its centerpiece, a splendid sarcophagus topped by marble effigies of the queen with her beloved Albert at her side.

Kodai-ji Temple, Japan

In the forested foothills of Kyoto’s Higashiyama Mountains, a graceful temple commemorates the son of a peasant who rose to become a samurai and helped unify Japan after centuries of feudal warfare. His name was Toyotomi Hideyoshi.

One of Kyoto’s most visited temples, Kodai-ji was commissioned by Hideyoshi’s grieving wife, Kita-no-Mandokoro, after his death in 1598. Also known as Nene, this widow became a Buddhist nun and lived for 19 years at Kodai-ji, where her grave is located. Although Hideyoshi was buried at a different site in Kyoto, his spirit resides at Kodai-ji with his wife, says David L. Howell, professor of Japanese history at Harvard University.

(Fall in love with 10 heart-shaped places around the world.)

“Although it’s hard to look into the hearts of long-dead warlords and their spouses, it does appear Hideyoshi and Nene were devoted to one another,” he says. “They remained together for about 37 years until Hideyoshi’s death. Like other powerful men at the time he had various concubines—he desperately wanted to produce a male heir—but he never repudiated Nene.”

‘Memorial to a Marriage,’ New York

In New York City’s Woodlawn Cemetery, two women’s love is sculpted in bronze and frozen in time. Called “Memorial to a Marriage,” this bronze mortuary sculpture was created by American artist Patricia Cronin in 2002, when same-sex marriage was illegal in the United States.

The work depicts Cronin with her then partner and now wife, Deborah Kass embracing beneath a bedsheet, and sits atop their future burial plot. Cronin describes it as the “world’s first marriage equality monument."

“Most LGBTQ+ people, their families, and allies live in communities here in the United States and many countries abroad where homophobia thrives,” Cronin says. “If you deeply love someone, this work is for you, regardless of your sexual identity.”

Woodlawn Cemetery is open to the public and holds frequent guided tours. A bronze replica is permanently displayed at Kelvingrove Art Gallery and Museum in Glasgow, Scotland.

Humayun’s Tomb, India

An inspiration for the Taj Mahal, Humayun’s Tomb in east Delhi, India, is a marble-and-red-sandstone treasure that tells the story of an emperor and the enduring love of his wife.

After Humayun, ruler of India’s Mughal dynasty, died due to a fall in 1556 at age 47, his first wife, Bega Begum, commissioned this tomb. It was the first large building made in Mughal architectural style—a blend of Indian, Persian, and Central Asian design elements, says Najaf Haider, a professor of Indian history at Delhi’s Jawaharlal Nehru University.

Haider says Begum, who became known as Haji Begum after a visit to Mecca, was “greatly attached to her husband and his memory,” he says. “As long as Haji Begum lived, she looked after the tomb.”

Mausoleum of Halicarnassus, Turkey

In the Turkish seaside city of Bodrum, tourists can wander the remains of a 2,300-year-old masterpiece. The Mausoleum of Halicarnassus was one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World and rivaled Egypt’s pyramids in size and grandeur, according to Daniel Sherer, visiting lecturer in architectural history and theory at Princeton University.

Sherer says first-century Roman author Pliny the Elder wrote that this mausoleum was commissioned by Queen Artemisia in 353 B.C. It was a grand gesture and eternal home for her partner, Mausolus, the ruler of Caria, a territory of what is now Turkey. In Renaissance and baroque art, Artemisia is often depicted supervising the tomb’s construction, Sherer says.

An account by first-century Roman historian Valerius Maximus depicts Artemisia as so devoted to her late husband that she mixed the ashes of Mausolus in a liquid which she then drank, “thereby making herself a living, breathing tomb,” Sherer says.

Rani-ki-Vav Stepwell, India

On the outskirts of Patan, a small city in western India, the earth opens up to exhibit an intricate wonder. A series of staircases take visitors past four pavilions and 1,500 hand-carved sculptures as they descend more than 65 feet into Rani-ki-Vav stepwell.

India once had thousands of stepwells, used to gather water for drinking, washing, and bathing, before British colonial forces destroyed most of them. Also known as the Queen’s Stepwell, Rani-ki-Vav was commissioned in the 11th century by Queen Udaymati, and extensively restored in the 1980s. She dedicated this jewel to her late husband, King Bhimdev I, who ruled a swath of what is now India’s Gujarat State.