Still Life

In the taxidermist’s hands, even extinct animals can look alive. But preservation is one thing, and conservation’s another.

Not every feat of taxidermy qualifies as art. But as the art of taxidermy has endured and evolved, it has given form to a paradox in wildlife conservation: that men and women passionate enough to kill have sometimes been passionate enough to protect.

An adolescent taxidermy student named Theodore Roosevelt grew up to be an avid big game hunter. He also co-founded a game preservation society that laid the groundwork for U.S. wildlife conservation today. For years I’ve investigated international wildlife crime, exposing its carnage in articles, documentaries, and a book, but it was my time as a boy taxidermist that helped set me on that path.

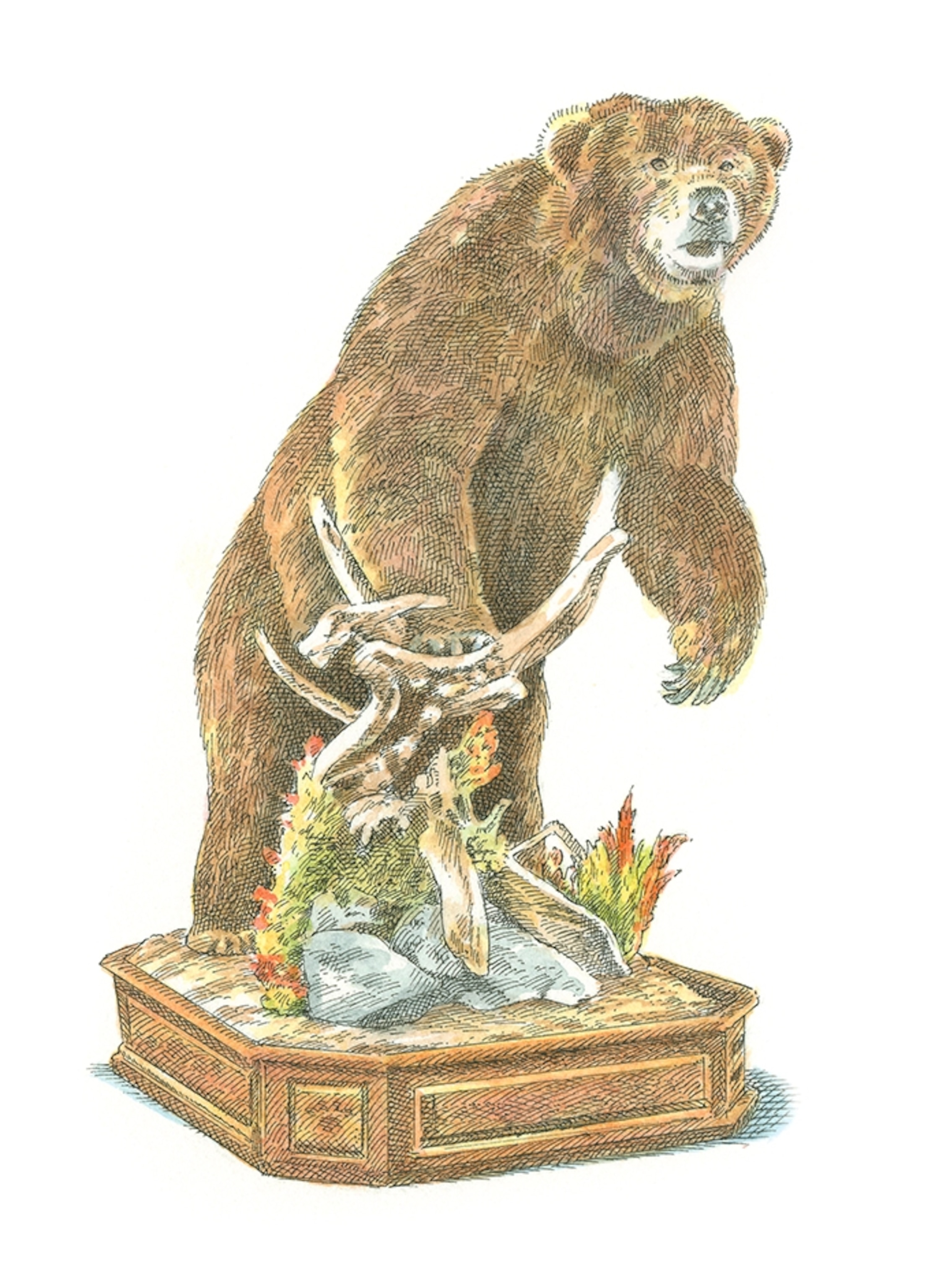

Since the 1800s, when hunters took their trophy kills to upholsterers to be stuffed, taxidermy has played an important role in conservation. Done well, it affords a close-range, still-life chance to appreciate creatures we might never encounter in the wild. We see them absent the bars of a zoo, arranged as they might be in nature—and there is “something elemental about that experience,” says Timothy Bovard, the taxidermist at the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County.

Which is why, after years of writing about criminally exploited wildlife, I have come to this global gathering of champion taxidermists eager for a respite—only to hear a woman shouting at Wendy Christensen, “That’s illegal!”

The incensed visitor is pointing at a mounted lowland gorilla as taxidermist Christensen teases a few hairs around the huge primate’s fingers. “I was in Rwanda,” the woman shouts, “and I know gorillas are protected!”

Christensen is an imposing woman whose blond hair—it’s impossible not to notice—is swept back a bit like her gorilla’s. Facing her accuser, she calmly explains that for three decades, Samson the gorilla was the star attraction at the Milwaukee County Zoo. The visitor apologizes, then gapes at what Christensen says next: This animal, a vessel for Samson’s story, contains no speck of real gorilla.

Strike a Pose

In the late 1800s Americans’ Manifest Destiny was consuming America’s boundless wildlife at a great rate. Professional market hunters killed game on an industrial scale to supply the fur, restaurant, millinery, and other trades. As if extinction were impossible, Americans killed millions of bison for profit and sport, so that by the end of the 19th century only a few hundred remained.

Passenger pigeons once were the most populous bird in America. In 1878 hunters for the restaurant trade descended on a large flock of the birds outside Petoskey, Michigan, and killed some 1 billion birds in a few weeks. By 1914 America’s last passenger pigeon was dead (and mounted by a Smithsonian taxidermist).

The list of butchered species goes on, much the way the list of African and Asian species under siege grows today.

Teddy Roosevelt was both naturalist and sportsman, as were the dozen friends he called together in late 1887. The men founded the Boone and Crockett Club (named after Roosevelt’s boyhood heroes) with intertwined goals: to promote federal wildlife conservation efforts and ensure themselves a huntable animal supply. The club established the New York Zoological Society, which would evolve into the Wildlife Conservation Society. John Muir modeled his Sierra Club on his friend Roosevelt’s organization. Among the latter’s influential members was William T. Hornaday, whose titles included director of the Bronx Zoo—and chief taxidermist for the Smithsonian.

I took up taxidermy at age 12. Like many World Taxidermy Championship competitors and the event’s director, Larry Blomquist, I got my start by enrolling in the Northwestern School of Taxidermy, an Omaha, Nebraska-based correspondence school that offers easy-to-follow courses. (Lesson One: Read this entire book. Lesson Two: Get a common pigeon. Lesson Three: Acquire tools—scalpel, bone scraper, brain spoon, arsenic …)

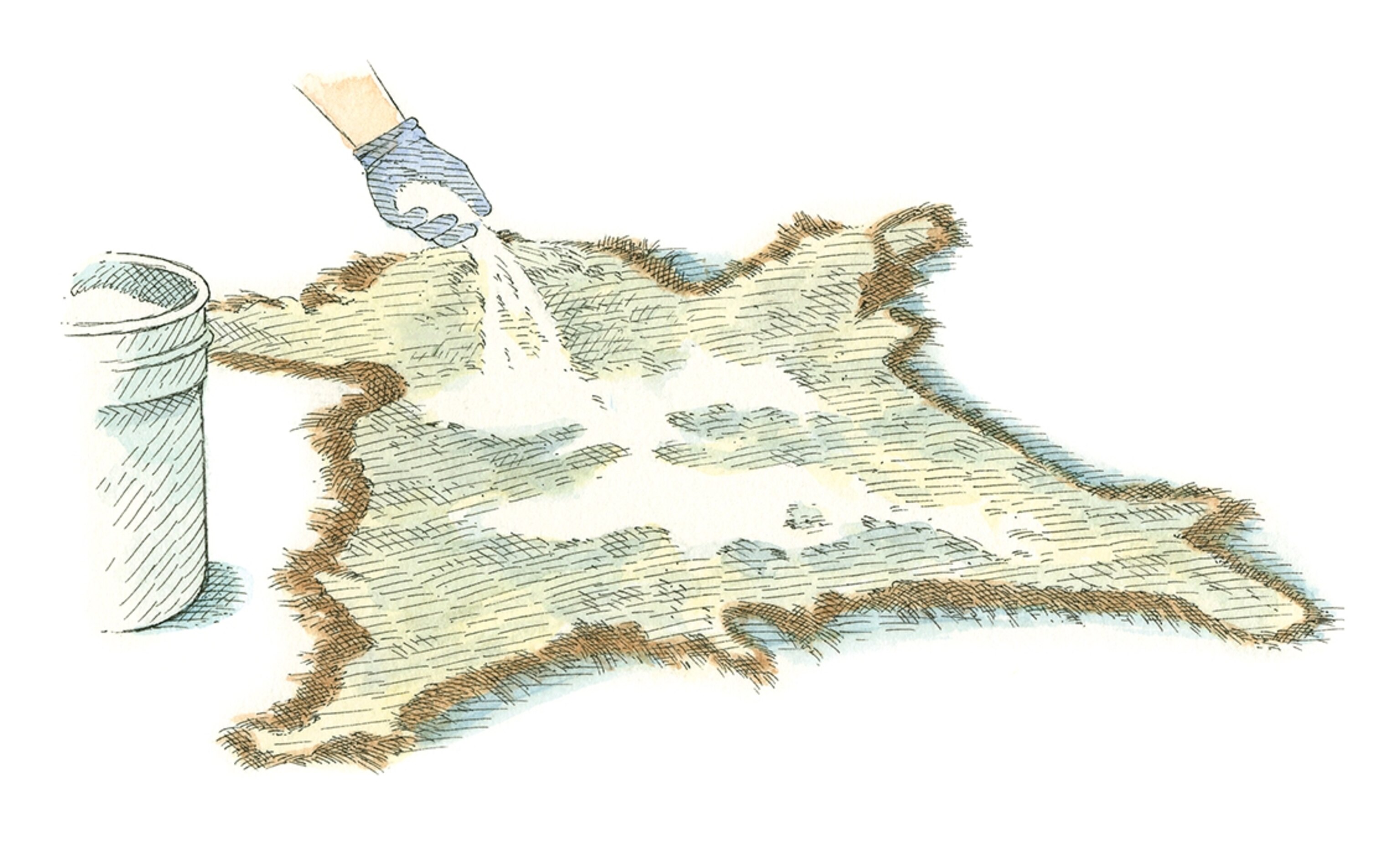

The father of modern taxidermy, as anyone who picked up a scalpel and a squirrel soon learned, was Carl Akeley. A New York–born naturalist and explorer, he single-handedly elevated taxidermy from a smelly form of upholstering—skin the animal, boil its bones, wire the frame back together, stuff the framed skin sack with rags and straw—to an art form.

He sculpted animal bodies into natural positions using clay and papier-mâché to render with unprecedented anatomical exactness a specimen’s muscles and veins before reapplying its skin. He then grouped his lifelike pieces in dioramas designed to re-create habitat, down to casting the individual leaves on the ground where an animal had been found.

Akeley introduced more than fresh mortuary techniques. He invented a narrative framework for us to consider dead animals, one that continues to this day. “The key to taxidermy is telling the whole story,” says Jordan Hackl, a 22-year-old novice competing at the championships. It’s not about stuffing a deer, he explains. It’s about telling the deer’s story. Was it winter? Then you better have a buck with the right hair length. Was he in rut? Is there a doe? Then you better have the nostrils flared.

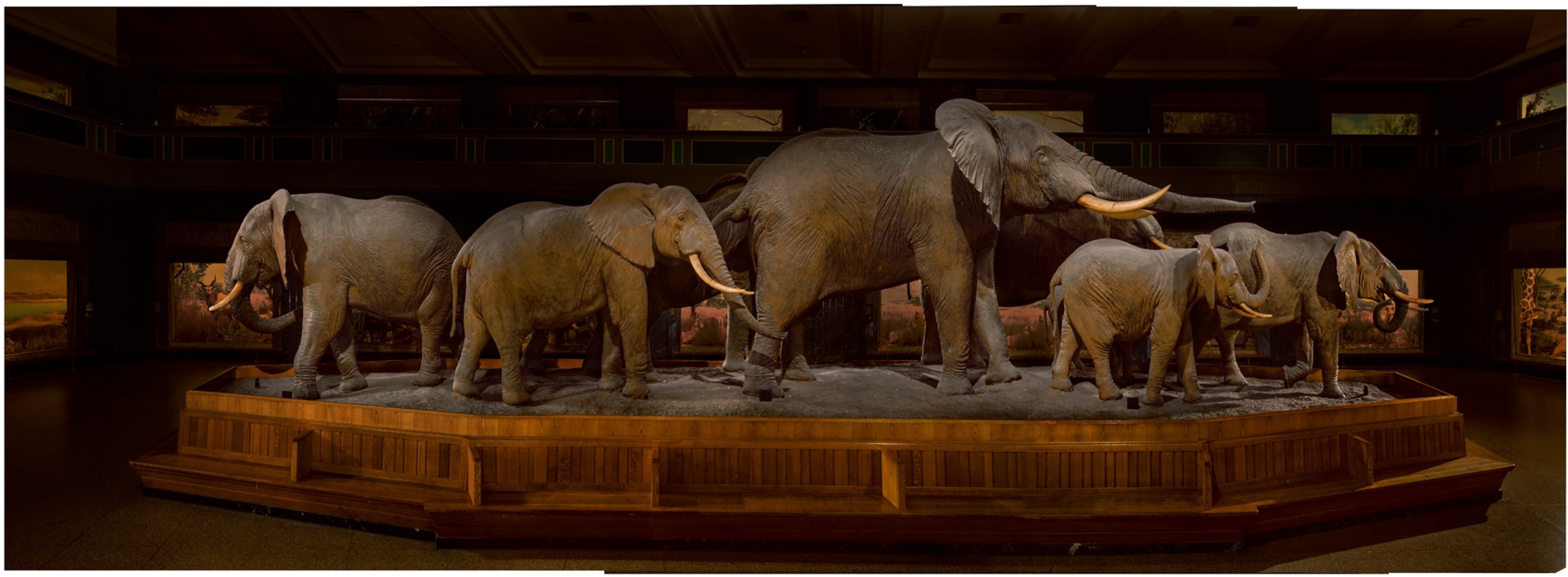

Akeley’s impact can be seen everywhere that an animal is eternally still. Some of his best known creations remain on display at the Field Museum in Chicago and the American Museum of Natural History (AMNH) in New York City.

In the center of AMNH’s Akeley Hall of African Mammals stands “The Alarm,” his tableau of a herd of eight elephants. A century old and still vibrant, it’s considered by many to be the world’s finest example of taxidermy.

Another work in the hall, though, may be Akeley’s most important. It’s a mountain gorilla diorama whose figures were killed by his team in the Belgian Congo in 1921. That trip changed Akeley’s life: Looking down on his dead silverback, he later commented, “it took all one’s scientific ardour to keep from feeling like a murderer.”

Upon his return from Africa, Akeley lobbied Belgium’s King Albert I to create a sanctuary for mountain gorillas. The Parc National Albert, established in 1925, was Africa’s first national park and today is called Virunga National Park. For his efforts, Akeley is recognized as a forefather of gorilla conservation.

In Akeley’s view taxidermy was a valuable scientific service, a way of preserving what he feared might go extinct. He wrote of that concern in this magazine’s August 1912 edition, in an article describing his hunt for the elephants used in “The Alarm.” Lamenting that the best bull he’d collected had tusks weighing only about a hundred pounds each, Akeley noted that elephants with 200-pound tusks weren’t uncommon. He hoped to collect one to preserve for future generations, he wrote, predicting that soon “the remaining monster specimens will be killed for their ivory.”

Today it is a rare sight to see an elephant with tusks weighing even a hundred pounds.

George Dante opens his freezer and lifts out Lonesome George, the last Pinta Island Galápagos tortoise, which died in 2012. One of the world’s most highly regarded taxidermists, Dante has been hired to preserve the famous animal.

Placing the frozen tortoise on a table, Dante says he’s worried that Lonesome George is too well known to do him justice in preserved form. It’s one thing to prepare a mount to represent a species, he says, and quite another if the creature has an individual, recognizable look. That’s why “I won’t do pets,” he says. “People know their pets’ faces too well, and you can’t capture that.”

Despite the tortoise’s time in cold storage, “Lonesome George looks in good shape,” says Dante, with a sigh of relief.

Samson the gorilla was another story.

A 652-pound, overfed lowland gorilla from Cameroon, Samson was famous for slamming his fists against his Plexiglas window at the Milwaukee County Zoo, delighting terrified visitors. One day in 1981, in front of his fans, Samson fell over and grabbed at his chest. Zoo vets could not resuscitate him; an autopsy revealed that he’d had five previous heart attacks.

Samson’s corpse was in the zoo’s freezer for years. When the Milwaukee Public Museum finally took possession, officials found the gorilla’s skin too damaged to mount. The museum tried putting Samson’s skeleton on display, but his bones were a weak evocation of the colorful ape. Samson wasn’t just dead, he was silenced.

That troubled museum staff member Wendy Christensen, who had taken up taxidermy when she was 12. (Yes, through the Northwestern School of Taxidermy.) Christensen proposed resurrecting Samson through the taxidermy variant called a re-creation—an artificial rendering of an animal that does not use the original animal or even its species. In 2006, 25 years after Samson’s death, she began fashioning the ape’s synthetic doppelgänger from scratch.

Christensen molded a silicone face using Samson’s plaster death mask and thousands of photographs. She ordered a replica gorilla skeleton from a vendor called Bone Clones and a mix of yak and artificial hair from National Fiber Technology, the company that supplied fur for Chewbacca, of the Star Wars movies. For Samson’s hands she took molds of gorilla hands from the Philadelphia Zoo and reproduced them in silicone, right down to the fingerprints. Next, she rimmed his synthetic eyes with false eyelashes bought at Walmart.

Then Christensen put herself on display. She spent a year at a raised workstation in full view of museumgoers, implanting hairs in Samson’s silicone face and neck, while children asked questions and parents shared fond memories of seeing the gorilla when they were young.

Among taxidermists, opinions are mixed on the use of synthetic versus actual animal materials. Bovard says that when he chats with visitors to his museum’s animal exhibits, they often ask him “which of our animals are real and which are not, and they do react differently to the two.” In an era when media and technology serve up versions of reality 24/7, Bovard says, there is still something powerful about the genuine article.

But that is only one perception. A judge at the World Taxidermy Championships wondered privately if the art form had gone too far. In the hunt for trophy-quality animals, he said, “we take the best genes out of the gene pool” to the detriment of the species.

When Christensen brought Samson to the championships, she was competing not only against other re-creations but also against the world’s best real-animal taxidermy. She won the top prize in the re-creations category. She also won the Judges’ Choice, Best of Show prize, beating out world masters who’d brought their finest—and real—wildlife effigies.

And she did it without harming a single gorilla hair.