Rock of Ages

Millions of years in the making, Vermilion Cliffs National Monument remains a little-known wonder.

Carry a lawn chair and a sunshade—plenty of water too—onto the sage flats just south of Arizona's Highway 89A, near the mouth of Badger Canyon. Point the chair north, toward Utah, and take a seat. Behind you, the Colorado River is trenching a deep meander from the Glen Canyon Dam toward the Grand Canyon. Directly in front of you rises a chaos of rock vaulting nearly 3,000 feet—the Vermilion Cliffs. The cliffs can hardly be said to have a face. They have innumerable faces, fractured and serrated, crosshatched and slumped. You can feel the inertia in their colossal vertical fissures. Along the lower wedding cake tiers, rubble piles resemble the sand in the bottom of an hourglass.

And now the question: How long would you have to wait until the Vermilion Cliffs calved a boulder the size of a school bus, say? The answer: It could happen the day you sit down. But it's likelier that your descendants' descendants would still be sitting in that chair, many hundreds of generations later, waiting for the cliffs to crumble a little more. The rock is ancient, and so are the traces of erosion.

Millions of years ago, the spot where you're sitting would have been buried under the exposed layering of the present-day cliffs, under strata now called Moenkopi, Chinle, Moenave, Kayenta, and Navajo, each striation differing in color and resistance to erosion. The Paria Plateau has been retreating northwestward for eons, and these vivid cliffs mark its progress to date.

It's hard to believe that a national monument girded by towering cliffs—their color burning through the spectrum as the day advances—could be so little known. Yet few people have heard of the place, apart from one or two of its famous features. One reason is that Vermilion Cliffs National Monument is upstaged by its neighbors, which include some of the most famous national parks and monuments in the United States: Grand Canyon, Zion, Bryce Canyon, and more.

Another reason is the ruggedness of the terrain. Though located only a few miles from Lake Powell and its legions of pleasure craft, the 300,000 acres encompassed by the monument are no place for the fainthearted or unprepared. "Exit the car, enter the food chain," quipped one official with the Bureau of Land Management, which administers the monument. The predators here are sun, heat, thirst, ignorance, and isolation. (Also rattlesnakes and scorpions.) There are almost no marked trails, only a few signposts, and none of the assurances, warnings, or rangers found in national parks. Here your cell phone doesn't work, you camp where you can, and the only water is what you carry.

The cliffs proper have been protected as wilderness since 1984. They form an irregular upside-down horseshoe, abrupt and sheer on the east side near the Colorado River, curving severely around to the south and shallowing on the west as they run up into Utah along House Rock Valley Road, one of the most beautiful dirt drives in the American West. Follow the arc of that horseshoe and the cliffs peer over you all the way, forbidding and beckoning at once.

But drive across the northern bench at the top of the horseshoe, heading from Page, Arizona, to Kanab, Utah, and you would never guess the cliffs are there. Hike out onto the Paria Plateau and you feel as though you're walking across an island in the sky. The cliffs are invisible below you, but you can sense their presence. This is what the world would be like if it were flat and ended precipitously at an edge in space. But when you come to the end of the plateau—high atop the Vermilion Cliffs—you see that the world still goes on, stepping its way shelf by shelf down to the Grand Canyon and beyond.

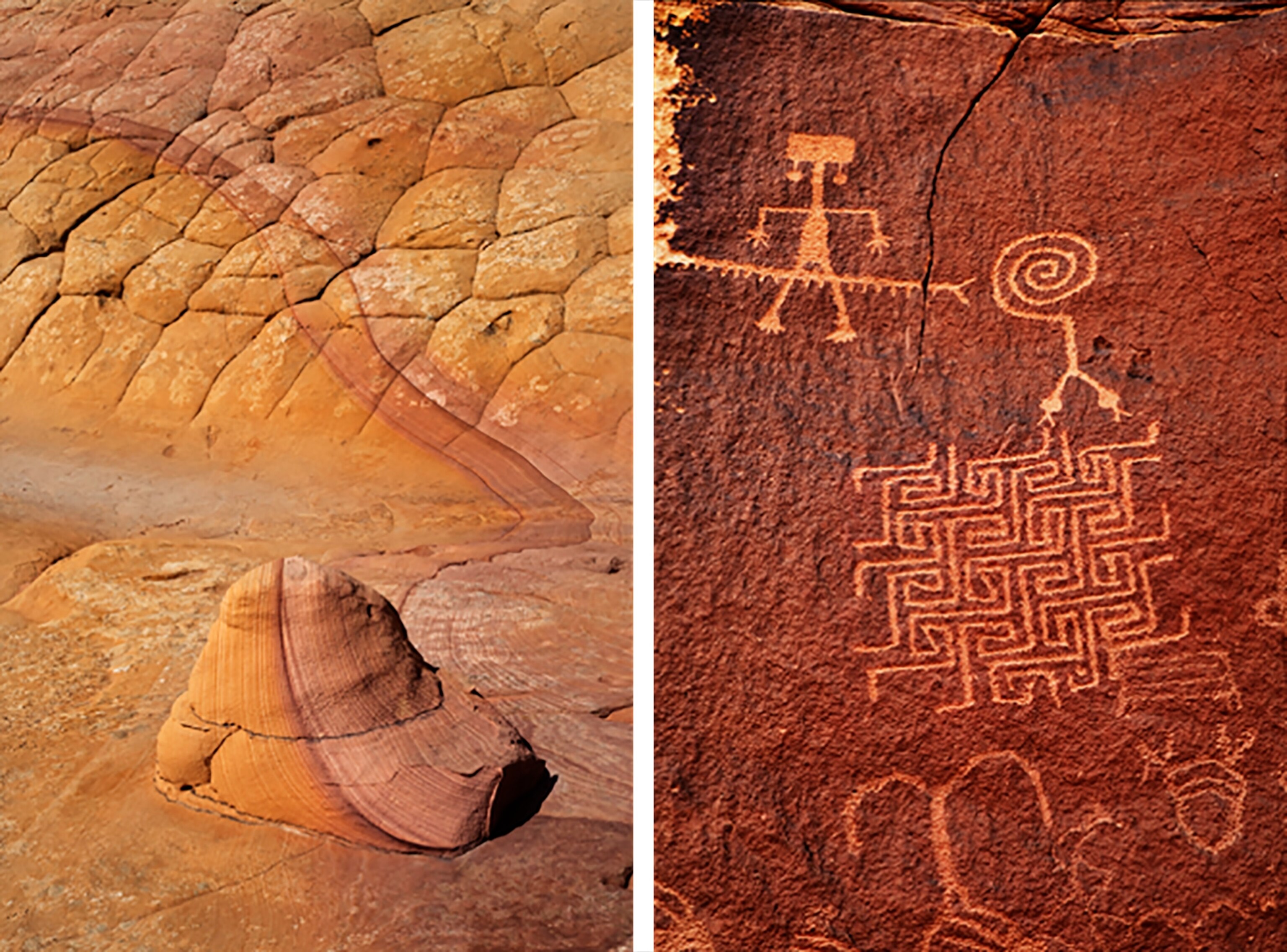

The Paria Plateau and its hem of cliffs were named a national monument by presidential proclamation in the year 2000, primarily in recognition of the exquisite archive of erosional forms—timescapes, windscapes, gravityscapes, and waterscapes but above all, sandscapes. There is the sand of the present day: the grit in your teeth, the slip-sink footing, the slithering tire-bog along the tracks in the Sand Hills mid-plateau. That sand (ancient enough, grain by grain) is derived from prehistoric sand—the Navajo sandstone that forms the plateau and cliffs. This sandstone, in turn, is the remains of a vast erg, a windblown sea of dunes that for millions of years covered most of what is now the Colorado Plateau. The geology is hard to imagine. It becomes even harder if you're lucky enough to come upon the Wave, hidden away in the northwest corner of the monument in a place called Coyote Buttes.

The Wave is a tumult of striped, fossilized dunes that look like petrified surf, forever rising and curving, towering just short of breaking. What's been left behind by long ages of erosion—rogue waves of smooth, banded sandstone in a bowl of light—is a record of chemical reactions taking place as the sandstone developed, with patterns of bleaching and the depositing of iron oxide and other minerals. In its sinuousness, the Wave forms a wind siphon, its geometry accelerating the wind the way a high, curving track accelerates a skateboarder.

Try to say the names of the colors you see glinting in the stone. They shift before you can do so. The sun pinwheels across the sky, clouds burgeon and fade, and the Wave evolves moment by moment without ever changing.

To safeguard this extraordinary formation, the BLM admits only 20 people a day to the Wave, so you're left nearly alone in a wilderness containing a geological "Mona Lisa." This isn't the South Rim of the Grand Canyon, a scenic view shared with thousands. Here is the intimacy of the senses: the abrasion of stone, the scent of rain on rock, a kaleidoscopic light that can leave you bewildered by the minute speck of time you occupy in the presence of so much frozen time.

The geological processes that shaped the Wave, as well as the cliffs and canyons and myriad landforms, continue unabated, of course. And yet they're hidden by the present. One afternoon I followed the dry creek bed of Buckskin Gulch on the west side of the monument, from a trailhead just off House Rock Valley Road. On the low hills around me lay bulging sandstone formations that looked like the pupae of some unaccountable insect. Tumbleweeds huddled in the creek bends like tired gray sheep.

Buckskin Gulch is famous for its slot canyon, but before I reached it I came to a high, perfectly undisturbed slope of loose red sand, as firm and uniform as the sand a wave leaves behind when it withdraws from a beach. Every grain seemed to know its place. It was sandstone in the making, uncongealed and awaiting diagenesis, the chemical transformation that would turn it into a slab of rock.

It's easy enough to see the stratigraphy in the layers of stone exposed on the cliff face, but there is also a stratigraphy of life-forms here, as well as a layering of human experience. Reach back far enough—190 million years and more, when this was a very different world—and you come to the ancient species, some crocodilian, some birdlike, that left their traces in the Navajo sandstone and in the formations that underlie it.

On the plateau, there are signs of more recent inhabitants in the few gnarled ranch structures up beyond a wire gate and into Corral Valley, high in the piñon and juniper. This landscape is not as spectacular as Coyote Buttes—almost nothing is—but it has its own private grace. Shallow basins in the sandstone catch every drop of rain. There are swales of arid grass and remnants of fence line that seem to exist only to keep the tumbleweeds in.

Thousands of years ago this landscape belonged to native hunters and gatherers, who must have passed through again and again. They were succeeded by the ancestral Puebloans, and later by the Paiute, who shared some of their knowledge of this country with a Mormon missionary named Jacob Hamblin. Hamblin, who settled in the House Rock Valley, knew the Vermilion landscape better than any other white man of his time. Explorer John Wesley Powell described Hamblin as a "silent, reserved man," adding that "when he speaks it is in a slow, quiet way that inspires great awe."

Hike down the Paria River Canyon, 38 wet-footed miles and at least four days from the trailhead to the Colorado River, and you come to the place where Powell and the battered remains of his first expedition camped on the night of August 4, 1869: the mouth of the Paria River, which Hamblin had described to Powell a year earlier. Preparing for his descent of the Colorado, Powell studied the terse account of Father Silvestre Vélez de Escalante, who, in 1776, tried to travel with his party from Santa Fe (in what is now New Mexico) to Monterey, California. He too camped near the mouth of the Paria River, hoping to find a more direct route back to Santa Fe. Powell described the cliffs in exuberant prose. Father Escalante said merely that the country had "an agreeably confused appearance."

Overwatching all these humans—itinerant or resident—would have been the birds now known as California condors (Gymnogyps californianus), which lived on the cliff edges high above. Generation after generation, they would have kept watch at intervals for at least the past 20,000 years—perhaps for as much as 100,000 years—diminishing as large Pleistocene mammals vanished. Condors have been missing from the Vermilion Cliffs since the early 20th century, but they are present again, reintroduced in 1996, their very small numbers supplemented by annual releases. From the condor viewing site on House Rock Valley Road, you're sure to see rocks high on the cliffs stained by their droppings.

How long until you see a condor? The good news is that the wait will take place in biological time, not geological time. While you're waiting—the Vermilion sun drying your flesh—you can imagine the sound of the wind in a condor's ears as it rises on an updraft and the view in its eyes as its head tilts from side to side, overwatching the plateau again.