Susan Potter will live forever

Susan Potter donated her body to science. It was frozen, sawed into four blocks, sliced 27,000 times, and photographed after each cut. The result: a virtual cadaver that will speak to medical students from the grave. National Geographic has been documenting Potter’s journey for 16 years.

Susan Potter knew in exquisite and grisly detail what was going to happen to her body after death.

For the last 15 years of her life, Potter carried a card with these words: “It is my wish to have my body used for purposes similar to those used in the Visible Human Project, namely that photographic images might be used on the Internet for medical education … In the event of my death … page Dr. Victor M. Spitzer, Ph.D. … There is a 4-hour window for the remains to be received.”

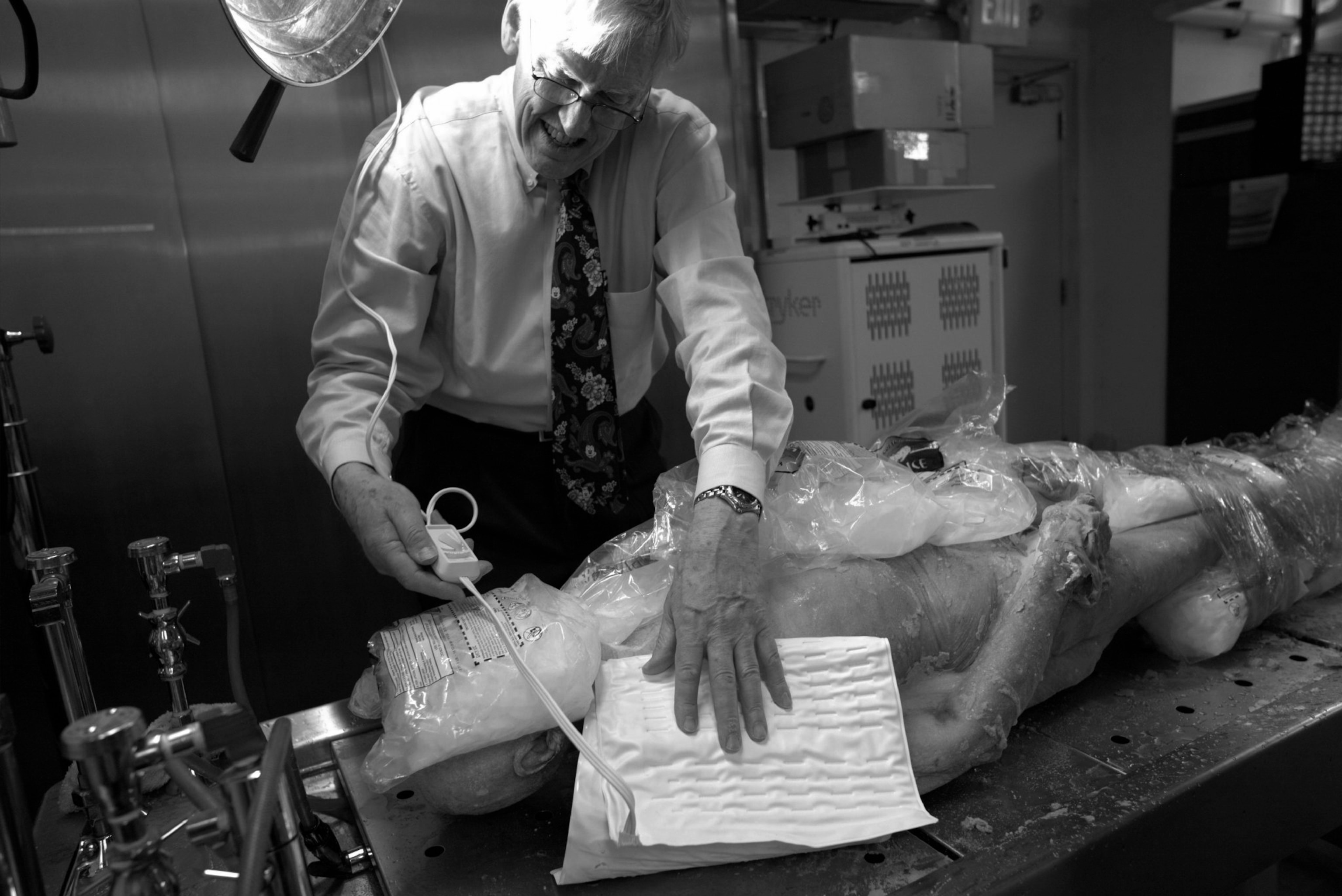

Potter knew because she visited the room where her body would be taken, saw the machinery that would grind her tissue away one paper-thin section at a time for imaging, and heard Spitzer, the director of the Center for Human Simulation at the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus, explain the process more than a decade before she died. Spitzer didn’t volunteer to show her the room; Potter demanded it.

I want to see the meat locker, she told him, meaning Room NG 004 in Fitzsimons, a former Army hospital on the grounds of the University of Colorado’s School of Medicine, near Denver. “I will only donate my body after a tour from top to bottom.”

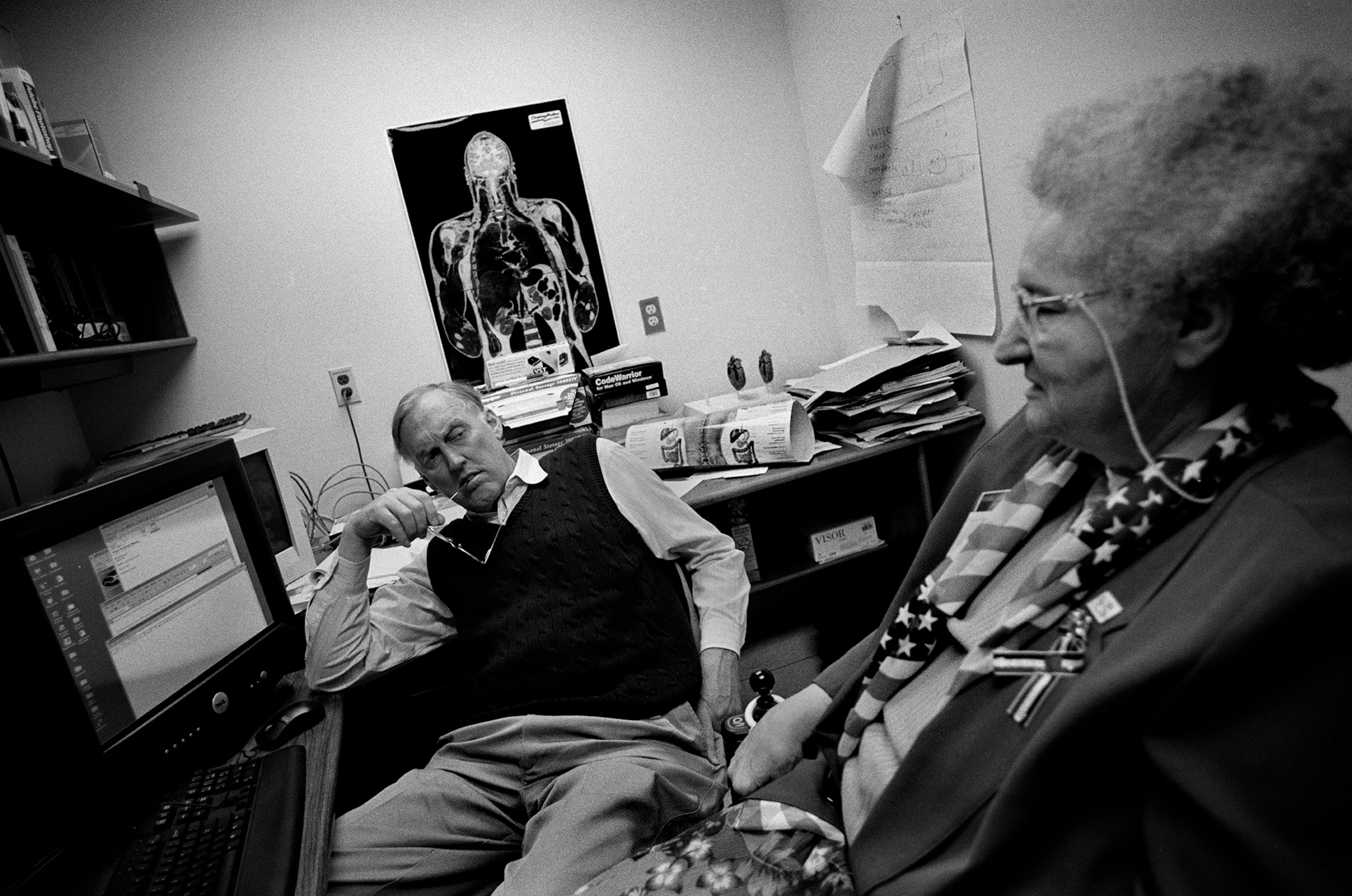

“This story is about death,” Vic Spitzer told me in March 2004, when I first met him to discuss his collaboration with Potter. “But in this case we’re talking about the future dead.” In fact, it’s really a story about a relationship between two living people: a scientist with a vision to create a boundary-stretching, 21st-century version of Gray’s Anatomy and a woman who volunteered for a project that would be realized only when she died. You could say that for the last 15 years of her life, Susan Potter lived for Vic Spitzer.

When Potter died of pneumonia at 5:15 a.m. on February 16, 2015, at the age of 87, her body was collected from the Denver Hospice, where she’d been admitted the week before. The cadaver, measuring five feet one inch from head to heel, 10 inches from back to front, and 19 inches from elbow to elbow, was placed in a freezer and frozen solid at minus 15 degrees F.

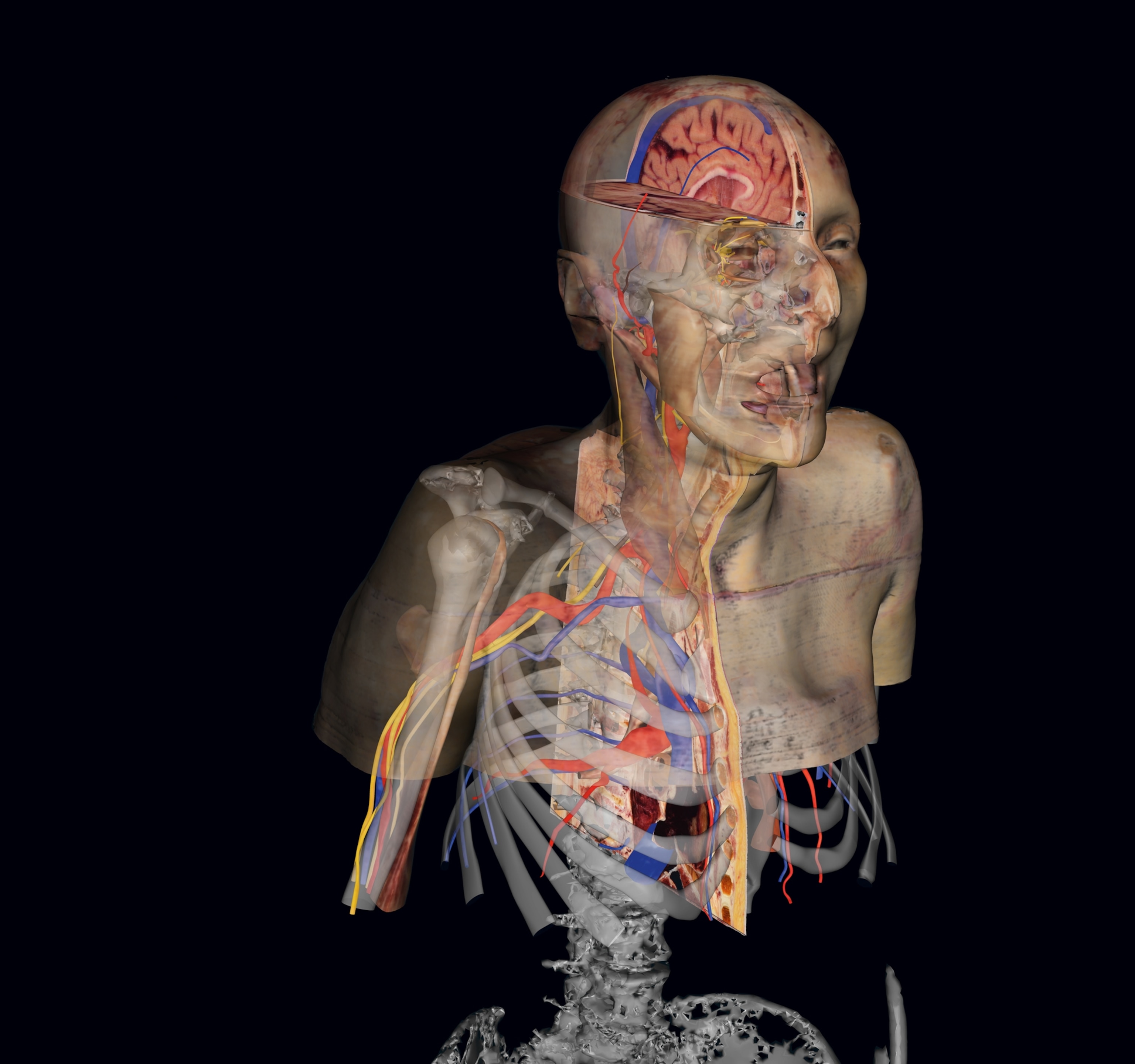

About two years later Spitzer and an assistant used a two-person crosscut saw to cut Potter’s frozen corpse into four sections, a preliminary step in an ongoing process that will take years. Ultimately, Spitzer will resurrect and reconfigure Potter’s body as a kind of digital avatar that can talk to medical students and help them understand how, in life, she was put together.

Anatomy is the bedrock of medicine. The body is what we present to our physician, says Robert Joy, professor emeritus of medical history at the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences. “The doctor asks, ‘What is happening, and where is it happening?’ To care for patients, the doctor must first learn the architecture of the body.”

To learn the where, medical students spend their first year dissecting a cadaver. “The dead teach the living” is a tenet of medicine.

In part because of the taboo against desecrating bodies, human cadavers weren’t used for education until the 14th century. Dissections were often done in public, but the students themselves didn’t dissect. A senior faculty member sat in a chair and read from the works of the Italian physician Mondino de Luzzi. A junior academic pointed out the structures. A barber or surgeon did the cutting. It was Andreas Vesalius, a professor at the University of Padua, who brought students to the dissecting table in the 1500s.

“Dissection becomes part of medical school with Vesalius,” says Mary Fissell, a professor in the Department of the History of Medicine at Johns Hopkins University. Greek physician Galen had dissected pigs, dogs, and apes. In the 1500s, Fissell explains, Vesalius pushed his own innovative-for-the-time point of view that human cadavers could best teach physicians human anatomy and, furthermore, that the student should do the dissection.

Dissection of a cadaver is like an archaeological excavation. To get to the deepest layers, one works from the top down. The process is anxiety provoking and enthralling—a medical school initiation rite with almost religious overtones.

“I remember the first time I held a heart in my hands,” Donald Jenkins (who died in 2017), a former anatomist at the National Library of Medicine, in Bethesda, Maryland, told me, with tears in his eyes, speaking of the female cadaver he worked on. “This is the heart when she was married,” he said. “I choke up when I think of it. It was profound.”

Today students spend less time in the anatomy lab because so much new science—the field of molecular genetics, for example—clamors for their attention. In the early 20th century, according to the late David Whitlock, former chair of the University of Colorado’s anatomy department, medical students spent a thousand hours studying anatomy. Now, says Wendy Macklin, chair of the Cell and Developmental Biology Department, it’s no more than 150 hours. A cadaver is a costly, nonrenewable resource. Medical schools don’t pay for cadavers but do pay for transportation, embalming, and storage. The 24 bodies used in the anatomy lab at the University of Colorado School of Medicine cost $1,900 each. (Every year about 180 people in Colorado donate their bodies for potential use in anatomy classes.)

Michael J. Ackerman, then the assistant director for high-performance computing and communications at the National Library of Medicine, had an epiphany. In 1987 he’d been speaking at the University of Washington about computer-based instruction in medical school. “After the lecture, the chairman of the anatomy department said, ‘If you want to use computers for instruction, you should use it for anatomy,’ ” Ackerman recalled in his office when I interviewed him in 2005. Anatomical dissection is tricky, he was told. If you do the dissection from the top, you can’t see how the anatomical structures relate to each other from the opposite side.

It was Ackerman’s eureka moment. Suppose a virtual cadaver existed, one you could endlessly dissect, then restore to Lazarus-like intactness with a keystroke?

That was the beginning of the National Library of Medicine’s Visible Human Project. In 1991 a team headed by Vic Spitzer and David Whitlock at the University of Colorado was awarded a government contract grant of $720,000 for the acquisition of digital image “data representing a complete normal adult human male and female … from cryo-sectioning … cadavers.” (The project, funded by the National Institutes of Health, eventually cost $1.4 million.) In short, Spitzer’s team was asked to slice male and female cadavers millimeter thin and photograph each section, so the images could be assembled into a digitized compendium of human anatomy.

Spitzer, who is six feet four, walks slightly hunched on the balls of his feet, which are often clad in brown leather sandals even in the dead of winter. He’s got a lean, angular face, a pronounced underbite, and a rapid-fire way of talking.

His specialty is anatomical imaging—the use of MRI and CT scans to figuratively turn the body inside out. His skill, shared with perhaps a handful of people in the world, is the full-body imaging of cadavers as a tool for medical education. Internal human geography is his passion. As a child, he was fascinated by the shoe-fitting x-ray fluoroscopes found in stores in the 1950s. He would slide his feet into the large wooden box of the apparatus and stare through the scope at the delicate arrangement of bones that enables humans to walk upright. His mother had to pull him away.

Years later, after studying physical chemistry at the University of Southern Colorado, he did graduate work in nuclear engineering and physical chemistry at the University of Illinois, where he met his wife, Ann Scherzinger, now also a professor at the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus. Then he found his way to medical physics—a field that includes the science of body imaging. It was a perfect fit.

It took Spitzer two years to find a suitable male body to cut for the Visible Human Project. “We were looking for a normal body, less than six feet tall, with no trauma or previous surgery. The body had to be fresh. And what,” he told me, “could be fresher than someone who is going to die on schedule? For this we needed a source. Which happened to be death row.”

The cadaver was supposed to be anonymous, but when the press found out that the first Visible Human was an executed convict in Texas, it was easy to come up with the name of Joseph Paul Jernigan.

The 39-year-old convicted murderer died from lethal injection at 12:31 a.m. on August 5, 1993. Spitzer flew to Texas to collect the body, which was frozen, sectioned into nearly 2,000 millimeter-thick slices, and digitized. The images are on the National Library of Medicine’s website, where anyone can file an application for the data.

The female, a 59-year-old from Maryland who had died of heart disease, was sectioned a year later. Spitzer’s group, having proved the technique to the National Library of Medicine, cut her into more than 5,000 slices only 0.33 millimeter thick. As of this writing, 4,000-plus licenses for the Visible Human data have been issued for applications ranging from building better hip joints to creating virtual crash dummies.

One day in a lecture hall on campus, I watched Spitzer demonstrate a dissecting program he’d devised using the data. With the sweep of a mouse, he stripped the musculature to reveal the skeleton, then showed a cross section of an upper thigh that looked like nothing so much as a raw haunch of meat. He isolated the circulatory system, hovered over the heart, visualized it from a different angle, and reassembled the cadaver in its entirety.

Although Spitzer continued to develop medical education software and procedure simulators for his own company, Touch of Life Technologies, the NIH-funded Visible Human Project formally ended with Jernigan and the female counterpart.

Then Susan Potter entered his life.

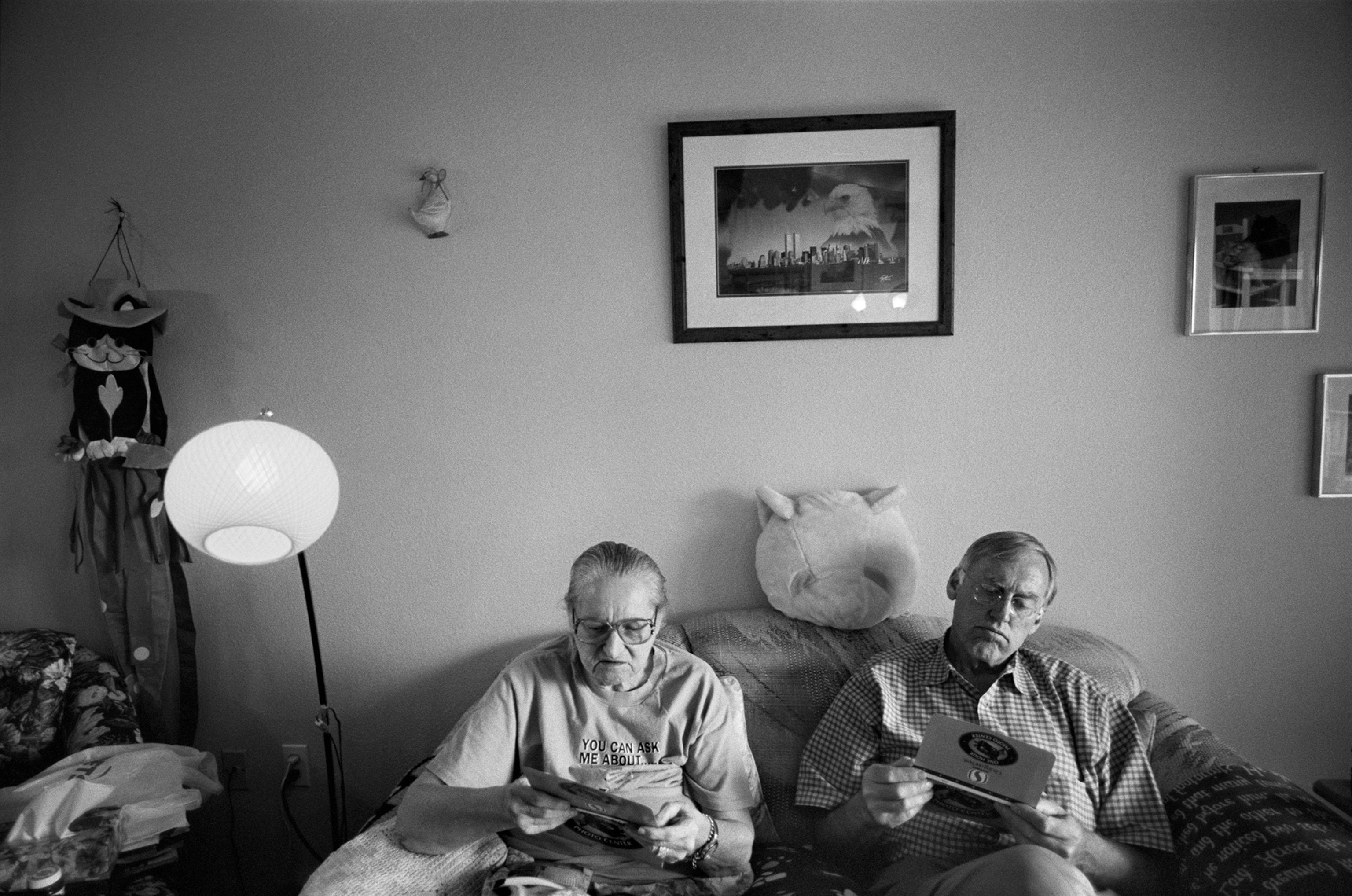

Born Susan Christina Witschel on December 25, 1927, in Leipzig, Germany, she had immigrated to New York after World War II. In 1956 she married Harry Potter, an accountant for a golf course on Long Island, where they raised two daughters. When her husband retired, the couple moved to Denver.

She was compactly built, with a face like a raptor and watery blue eyes that narrowed when she was displeased. She spoke with the inflection of her native Germany. Because injuries from an automobile accident made walking difficult, she used a motorized wheelchair—propelled as much by a get-out-of-my-way sense of urgency as by the chair battery.

By the time she met Spitzer, Potter, then 72, had been a presence around the grounds of the University of Colorado hospital for years. An activist for disability rights, she’d once rolled her wheelchair into a boardroom meeting chaired by the university chancellor, unannounced, waving a list of demands. (“If there is a stairway to heaven, it will be wheelchair accessible thanks to Susan,” one of the speakers at her memorial service observed wryly.)

One day in 2000, Potter called Spitzer’s office and got Jim Heath, his research assistant, on the phone.

“I’m Sue Potter,” she said. “I read about the Visible Human in the newspaper, and I want to donate my body.

“I want to be cut up.”

“She shocked me,” Spitzer recalled. “She rolled in and started to talk about becoming a Visible Human.”

Initially he wasn’t interested. You don’t fit, he told her. The Visible Human Project was about dissecting normal, healthy bodies. Potter’s body had been deformed by decades of illness, including a double mastectomy, melanoma, spine surgery, diabetes, a hip replacement, and ulcers. “But I knew I was lying,” Spitzer said. “I knew that one day we would need to start considering the diseased body,” the type that doctors deal with routinely.

Spitzer envisioned an advanced version of the Visible Human Project. Are you interested in working with us before you die? he finally asked her. Are you interested in giving us more than just your body—in giving us your personality and knowledge?

Spitzer wanted to videotape her while she was living and record her talking about her life, her health, her medical history. Your pathology isn’t that interesting to the project, Spitzer told Potter. But if I could capture you talking to medical students, when they’re looking at slices of your body, you could tell them about your spine—why you didn’t want the surgery, what kind of pain the surgery caused, and what kind of life you led after the surgery. That would be fascinating.

“They’ll see her body while they’re hearing her stories,” he explained, adding that video and audio of her would make her more real and introduce the element of emotion to students. Instead of an anonymous cadaver, this “visible human” would be capable of delivering a medical narrative suffused with the recollection of frustration, pain, and disappointment. The images of Potter, like those of the Visible Humans, would be on the internet, available anywhere, anytime.

Susan Potter had signed on to be an immortal corpse.

Dissecting a body is one thing. Teasing apart the tissue of human motivation, another. My first meeting with Potter, in 2004, took place at a nursing care facility where she was recovering from an infected leg suffered from a fall in her apartment in Aurora, the Denver suburb where she lived alone.

Photographer Lynn Johnson had been following her for several years, but Potter had steadfastly refused to see “the writer,” as she called me. She relented when Spitzer explained that the magazine project would need the participation of someone to write the story.

When Johnson, Spitzer, and I walked into her room, she was sitting in an armchair. It was just before lunchtime, and Potter was about to initiate an inquisition.

“You don’t call,” she snapped at Spitzer before any of us had a chance to say anything.

“You’re asking me to call you more than I call my mother,” he replied.

She remained impassive. “Then you should call your mother more.”

During the decade and a half that he dealt with Potter, Spitzer met with her more frequently in the beginning—usually for lunch in the hospital cafeteria. “The more you respond to her, the more she’ll consume,” he once said to me. “I think she would want me to visit her daily. She gets upset with me when I don’t answer the phone or when I go out of town.” He sounded exasperated but oddly tender.

She was like that with her doctors as well. She was always firing one doctor and acquiring another.

“How much time do you want a doctor to spend with you?” Spitzer once asked her, when she complained about a surgeon. “What if there’s someone else dying?”

She’s needy, isn’t she? I said when he told me the story. “Yeah, sure,” he replied. “Most of us are. Most of us want our hand held.”

Spitzer made it clear that she could revoke her decision anytime.

“I never crossed the line and wanted her to die,” he told me. “She knew what she was doing. I saw myself as conforming to her wishes. In all those years she never wavered.”

If anyone wavered, it was Spitzer. He needed to stay convinced, he once told me, that the project would have a positive impact on health care education.

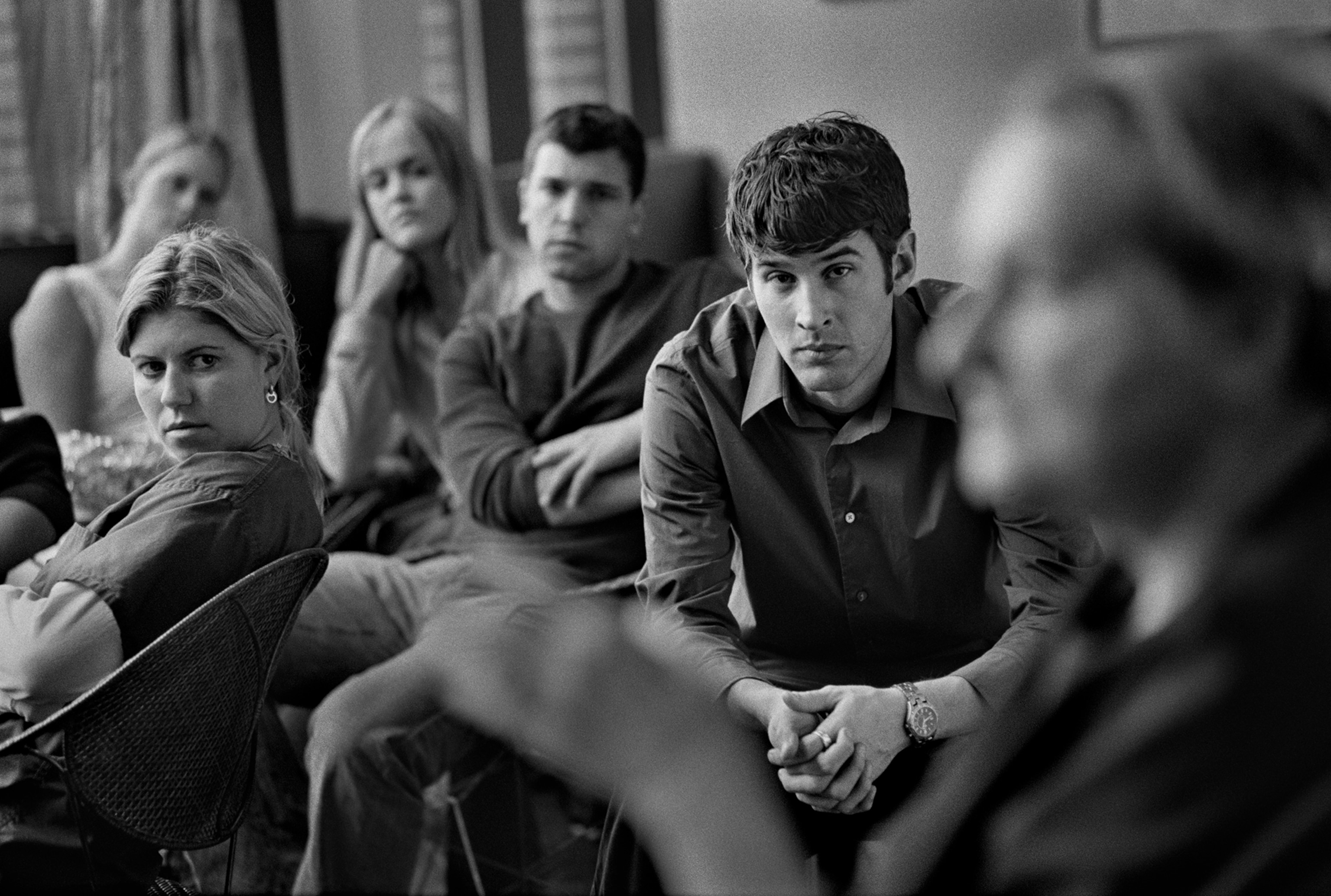

As a rule, a donated body remains anonymous. In the dissecting lab a donor list reveals age and cause of death, never a name. The head and face—the features most likely to provoke an emotional reaction—are dissected last and remain wrapped until the end. But Potter’s donation was a public affair. She appeared at a Visible Human Project conference with Spitzer as well as in front of informal groups of medical students.

Once a staffer in her geriatric clinic accused her of seeking notoriety. “You just want your name on the wall,” he told her.

Potter bristled. “If I can help young people become better doctors, that’s my purpose,” she retorted.

She was a woman of sharp edges, narcissistic, sometimes nasty, but also generous and caring. She knitted blankets and caps for premature babies in the hospital, volunteered at the hospital gift shop—until she was kicked out for carelessly running over a man’s foot with her wheelchair—and “adopted” a group of first-year medical students (Team Susan, they called it) whom she’d invite to lunch, give presents to, and lecture on the need for compassion—something, she made clear, many of her doctors could use more of.

When the visits from “her kids,” as she called the students, diminished as they became overwhelmed by the demands of medical school, she badgered Norma Wagoner, the anatomy instructor who’d formed the group, to put together another.

“Of course I disappointed her by not jumping to do it again,” Wagoner told me, “but she didn’t understand how difficult it was for the kids. She has no idea other people have lives too. She sucks you in. Everything is a drama.”

“What did you learn from Sue?” I asked Josina Romero O’Connell, one of Wagoner’s most empathic students, years after she’d graduated from medical school and become a practicing physician.

She hesitated. “Patience,” she finally said.

There was reason for the insatiable need for attention. Potter had endured a life of crushing abandonment. Her parents had left for the United States without her, leaving her as a young girl in Hitler’s Germany with her grandparents, in a city that would be heavily bombed during World War II. When she was four, her beloved grandfather dropped dead from a massive heart attack. Ten years later her grandmother died. She ended up in an orphanage before going to stay with an aunt. When she finally arrived in New York after the war, neither parent—by then divorced—was at Idlewild airport to greet her.

She had survived a litany of loss and the war in Germany, but the emotional price was steep. “I have the skin of a hippopotamus,” she once told me.

Tell me your favorite opera, I asked during one of my early visits, knowing she’d grown up in one of the most musical cities in Europe.

“Faust,” she replied.

And who in your production would play the role of the devil?

“My mother,” Potter said. “I’ve never been able to forgive that woman.”

The younger of Potter’s two daughters was in contact with her mother before she died, but neither attended the memorial service. Judging by the stories Potter told me, the relationship had been complicated and thorny, and she ordered me never to call them.

The bargain Potter made with the man who would cut her into 27,000 slices undoubtedly added meaning to her last years. In fact, it probably added years to her life. I was led to believe she was going to die within a year because of her multiple health problems. She lived for another decade.

Predictably, she tried to control the project after death too. She wanted classical music to be played during her “cutting” and the room to be filled with red roses. She wanted her teddy bear to be frozen and sliced with her.

Spitzer told her to forget that part.

“When are we going to see the pictures Lynn is taking?” she once asked me.

“You won’t,” I said, taking a deep breath. “They won’t be published until you’re dead.”

She didn’t blink.

The collaboration between the scientist and the donor reached its denouement on Friday, April 7, 2017. Spitzer had tried to get funding for his project, but the National Library of Medicine and potential corporate sponsors were not interested. He proceeded on his own, drawing on his company’s funds and the help of graduate students in anatomy. Cutting Sue was a promise to be kept. And so, two years after her death, Spitzer and several students stood in NG 004, the room where 17 years earlier Potter had taken a tour in anticipation of this moment.

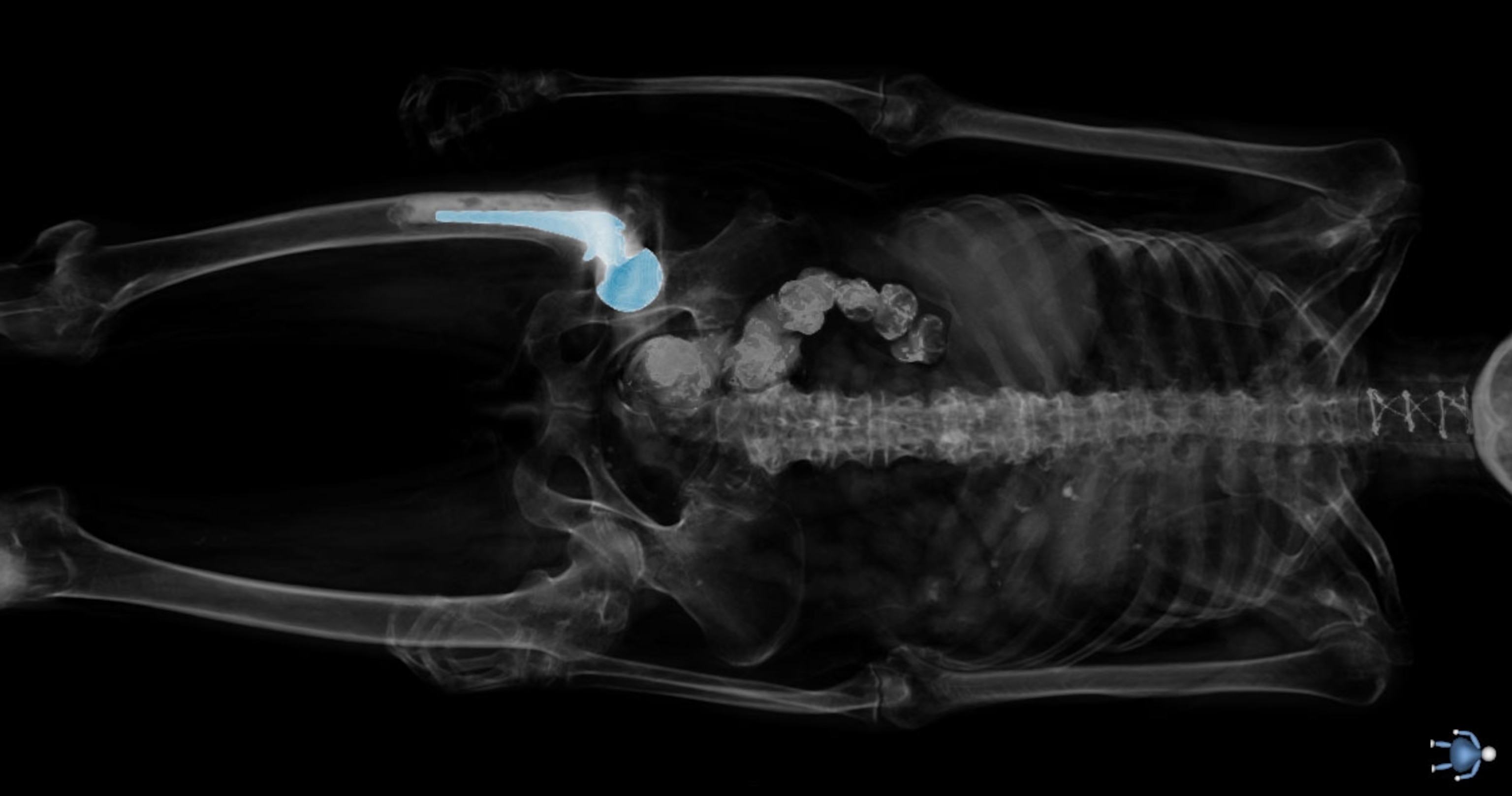

Spitzer placed the torso, encased in a block of blue polyvinyl alcohol, on a stainless steel table in the chilled room. A carbide blade the size of a dinner plate began to grind off tissue in hair-thin, 63-micron increments.

After each pass of the blade, a digital camera photographed each exposed surface of the block. Imagine incrementally sanding a block of wood and photographing the layer of surface grain exposed each cycle. As with a block of wood, what’s left of the corporeal Susan Potter is dust.

Spitzer had commissioned two students to paint red roses—not the fresh flowers Potter had requested, but close enough—over the door to the cutting room.

At 4:50 p.m., the blade, computerized and capable of running 24 hours a day, began to section her torso, and on a monitor in an adjoining room you could see the brown of liver, the gold of adrenal glands, and the marble of fat and muscle as cross sections of frozen tissue were ground down and photographed. In a bow to another of Potter’s requests, a graduate student streamed classical music into a speaker system.

It was Mozart’s Requiem.

Cutting the NIH-funded Visible Human Male into roughly 2,000 slices took Spitzer four months in 1993. Twenty-four years later, Susan Potter was cut into 27,000 slices in 60 days. Next comes the painstaking, time-consuming process of outlining the structures—tissue, organs, vessels—on each digital slice to highlight the skeleton, nerves, and vasculature in exquisite detail. That will take two or three years.

Now when Spitzer looks at Potter on the screen in digitized slices, he says, he sees her pain: the tortured, twisted arteries, the steel screws that stabilized her fractured cervical spine, an oddly misshapen kidney, and the arthritic joints that map the relentless decline into old age.

As for bringing Potter to life—having her interact with the viewer—that, Spitzer says, is a long-horizon endeavor. “I expect her to talk to you like Siri,” he said, though he admits that piece of it will be for someone else to realize. Long after her death, Potter will still be a work in progress.

Spitzer often lectures on the Visible Human Project, and on my first visit to Denver back in 2004, I watched him talk to a group of high school students.

He explained the project and its applications—how the images are used in the anatomy lab as a reference while students dissect an actual cadaver, how simulators based on the data allow surgeons to practice their skills. On a virtual patient a scalpel slip is not fatal—it’s just part of the learning process. He told his rapt student audience about Susan Potter and his vision of extending the Visible Human Project’s scope.

“Ultimately we want a body to act like it’s reacting to the outside world,” he said.

“When will you stop?” a student asked, perhaps wondering just how far the science of digital resurrection could be pushed.

“Never,” he replied, then added: “When the body gets up and walks away, then we’ll be almost done.”