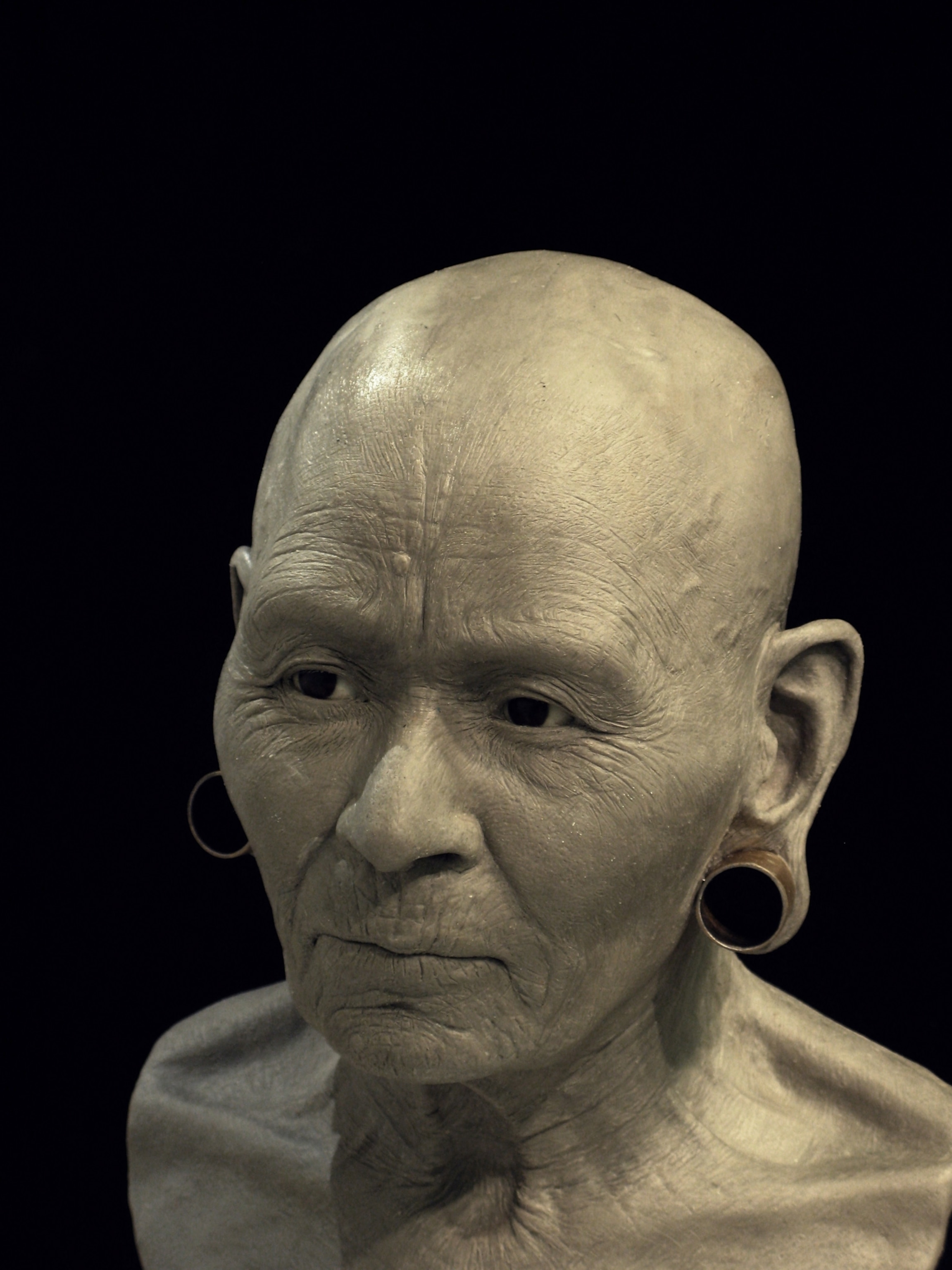

Face of Ancient Queen Revealed for First Time

Centuries after a noblewoman lived and died in Peru, scientists have reconstructed her face in stunning 3-D.

Some 1,200 years ago, a wealthy noblewoman, at least 60 years old, was laid to rest in Peru—richly provisioned for eternity with jewelry, flasks, and weaving tools made of gold.

Now, more than five years after her tomb was found untouched outside of the coastal town of Huarmey, scientists have reconstructed what she may have looked like.

“When I first saw the reconstruction, I saw some of my indigenous friends from Huarmey in this face,” says National Geographic grantee Miłosz Giersz, the archaeologist who co-discovered the noblewoman’s tomb. “Her genes are still in the place.”

In 2012, Giersz and Peruvian archaeologist Roberto Pimentel Nita discovered the tomb El Castillo de Huarmey. The hillside site was once a large temple complex for the Wari culture, which dominated the region centuries before the more famous Inca. The tomb—which looters miraculously missed—contains the remains of 58 noblewomen, including four queens or princesses.

“This is one of the most important discoveries in recent years,” said Cecilia Pardo Grau, the curator of pre-Columbian art at the Art Museum of Lima, in an earlier interview. (Read more about the amazing find in National Geographic magazine.)

One of these women, nicknamed the Huarmey Queen, was buried in particular splendor. Her body was found in its own private chamber, and it was surrounded with jewelry and other luxuries, including gold ear flares, a copper ceremonial axe, and a silver goblet.

Who was this woman? Giresz’s team carefully examined the skeleton and found that like many of the site’s noblewomen, the Huarmey Queen spent most of her time sitting, though she used her upper body extensively—the skeletal calling cards of a life spent weaving.

Her expertise likely explains her elite status. Among the Wari and other Andean cultures of the time, textiles were considered more valuable than gold or silver, reflective of the immense time they took to make. Giersz says that ancient textiles found elsewhere in Peru may have taken two to three generations to weave.

The Huarmey Queen, in particular, must have been revered for her weaving; she was buried with weaving tools fashioned from precious gold. In addition, she was missing some of her teeth—consistent with the decay that comes with regularly drinking chicha, a sugary, corn-based alcoholic beverage that only the Wari elite were allowed to drink.

Giersz’s team also has found a canal that leads from the Huarmey Queen’s tomb to outside chambers which bears residues of chicha. The channel would’ve allowed people to ceremonially share liquids with the noblewoman, even after her tomb was sealed. “Even after her death, the local population was still drinking with her,” says Giersz.

But what did this powerful noblewoman look like? In the spring of 2017, Giersz consulted with archaeologist Oscar Nilsson, renowned for his facial reconstructions, to bring the Huarmey Queen back to life.

Nilsson isn’t the first to try reconstructing the faces of South America’s pre-Columbian elite. Recently, archaeologists resurrected the Señora of Cao, a young female aristocrat who lived 1,600 years ago in ancient Peru’s Moche culture. (See how CSI tools brought the Señora of Cao back to life.)

Unlike that reconstruction—which was done almost entirely with computers—Nilsson took a more manual approach for the Huarmey Queen. Using a 3-D printed model of the noblewoman’s skull as his base, Nilsson rebuilt her facial features by hand.

To guide him, Nilsson relied on the skull’s construction, as well as datasets that let him estimate the thickness of muscle and flesh atop the bone. For reference, he also used photographs of indigenous Andeans living near El Castillo de Huarmey. (Chemical data confirm that the Huarmey Queen grew up drinking the local water, justifying the comparison.)

In all, it took Nilsson 220 hours to rebuild the noblewoman’s thoughtful visage, with no detail too small to ignore. To reconstruct her haircut—which the arid climate had preserved—Nilsson used real hair from elderly Andean women, which Gilesz had bought in a Peruvian wig-supply market.

“If you consider the first step to be more scientific, I gradually come into a more artistic process, where I need to add something of a human expression or spark of life,” says Nilsson. “Otherwise, it’d look very much like a mannequin.”

Some will get the chance to see Nilsson’s masterpiece in person. The finished reconstruction will be on public display beginning December 14, at a new exhibit of Peruvian artifacts opening at the National Ethnographic Museum in Warsaw, Poland.

“I’ve worked with this for 20 years, and there are many fascinating projects—but this one was really something else,” says Nilsson. “I just couldn’t say no to this project.”