Year after year, as autumn in Alaska is ending, Ryota Kajita goes looking for winter’s first ice. A Japanese-born photographer living in Fairbanks, Kajita believes that “everything—even if it appears to be insignificant—connects to larger aspects of our Earth.” An example, he says, is the ice, after it has frozen over ponds and lakes but before it’s been obscured by snow.

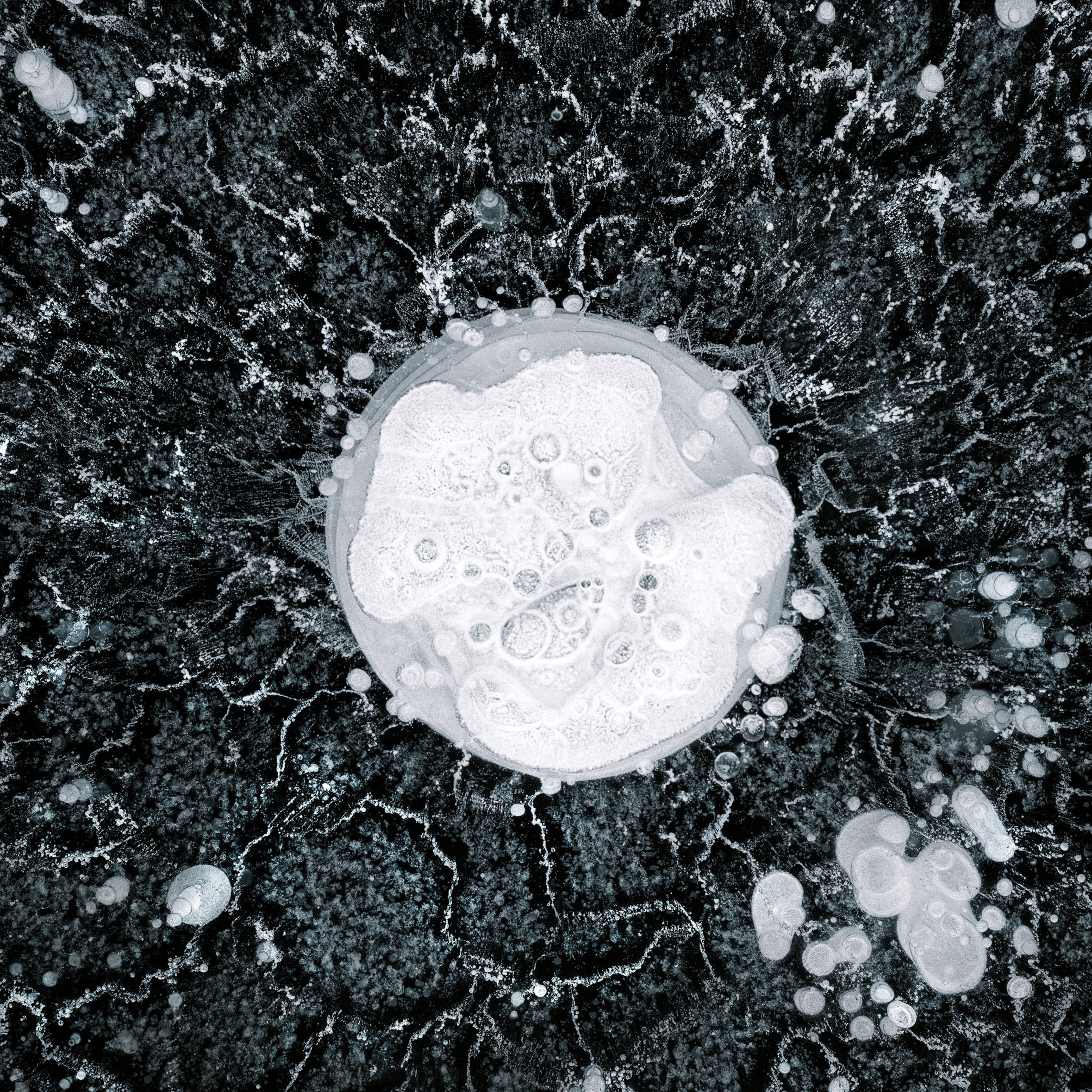

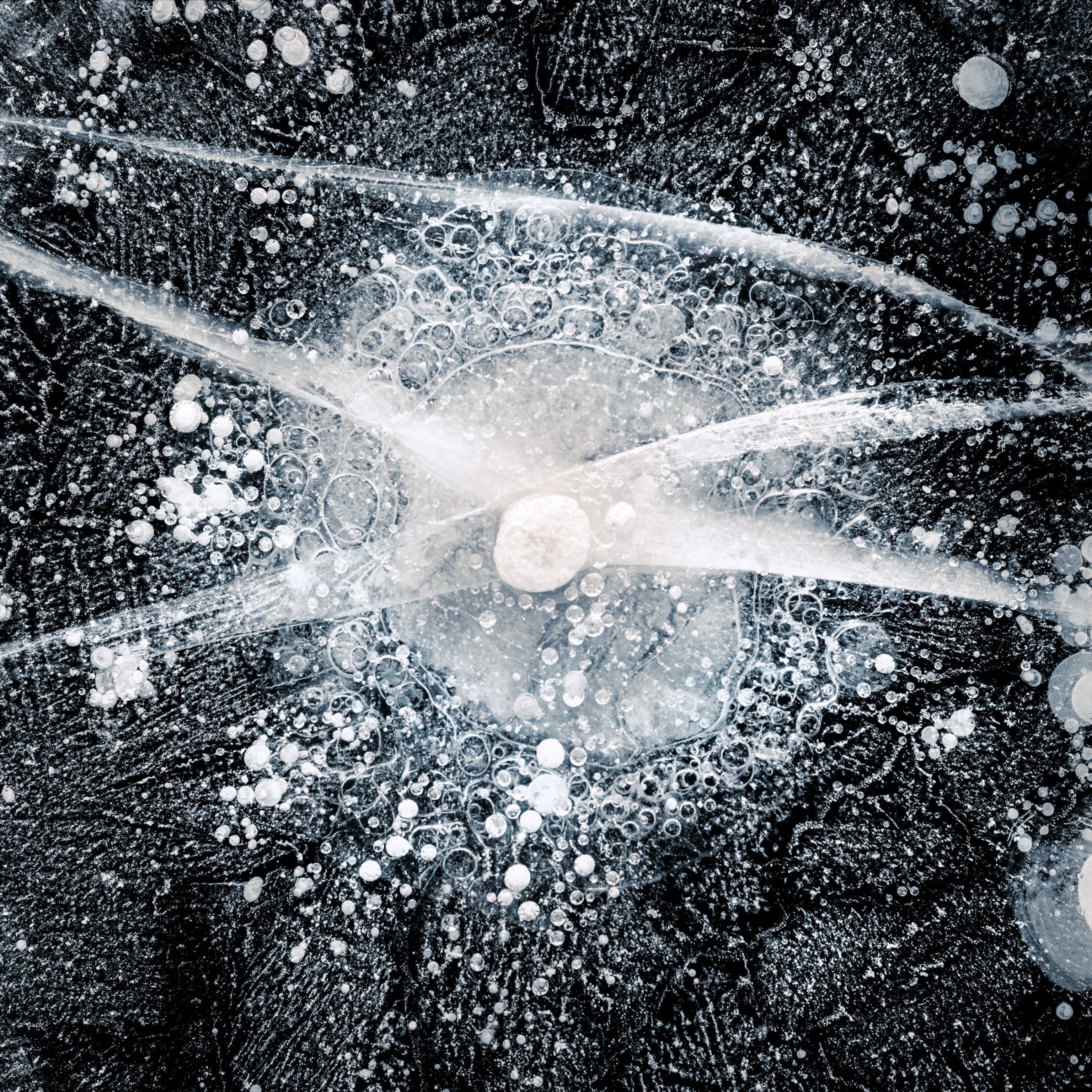

Kajita has been shooting photos through the ice since 2010 for his project, Ice Formations. He’s captivated by the geometric patterns he sees: fizzy fields of bubbles under the frozen surface, and snow and ice crystals dusted across it. Many photos are compositions of trapped, frozen bubbles of methane and carbon dioxide.

Though Kajita loves to photograph the formations, their existence worries him. As Earth’s northern regions warm, the thawing of permafrost accelerates. That releases more methane, a harmful greenhouse gas.

Kajita hopes people who see the photos will “feel connected to nature”—and that connection will help them “face bigger issues, like global climate change.”