Why we won’t avoid a climate catastrophe

By not doing enough to fight global warming, we’re trashing the planet. Innovation may save us, but it will not be pretty.

“A unique day in American history is ending,” Walter Cronkite intoned on the CBS Evening News on April 22, 1970. The inaugural celebration of Earth Day had drawn some 20 million people to the streets—one of every 10 Americans and a way bigger crowd than the man who’d dreamed up the occasion, U.S. senator Gaylord Nelson, had anticipated. Participants expressed their concern for the environment in exuberant, often idiosyncratic ways. They sang, danced, donned gas masks, and picked up litter. In New York City they dragged dead fish through the streets. In Boston they staged a “die-in” at Logan International Airport. In Philadelphia they signed an oversize, all-species “Declaration of Interdependence.”

(How Does a Gas Mask Protect Against Chemical Warfare?)

“Earth Day did exactly what I had hoped for,” Nelson, a Democrat from Wisconsin, would say later. “It was truly an astonishing grassroots explosion.”

I’m old enough to have been around for the first Earth Day, and though I have no recollection of having joined in the festivities, I’m very much a product of that “unique” moment, with its die-ins and its declarations. I spent the seventies protesting in the rain, trying to persuade my classmates to recycle their soda cans, wearing bell-bottoms printed with giant purple flowers, and worrying about the future of the planet.

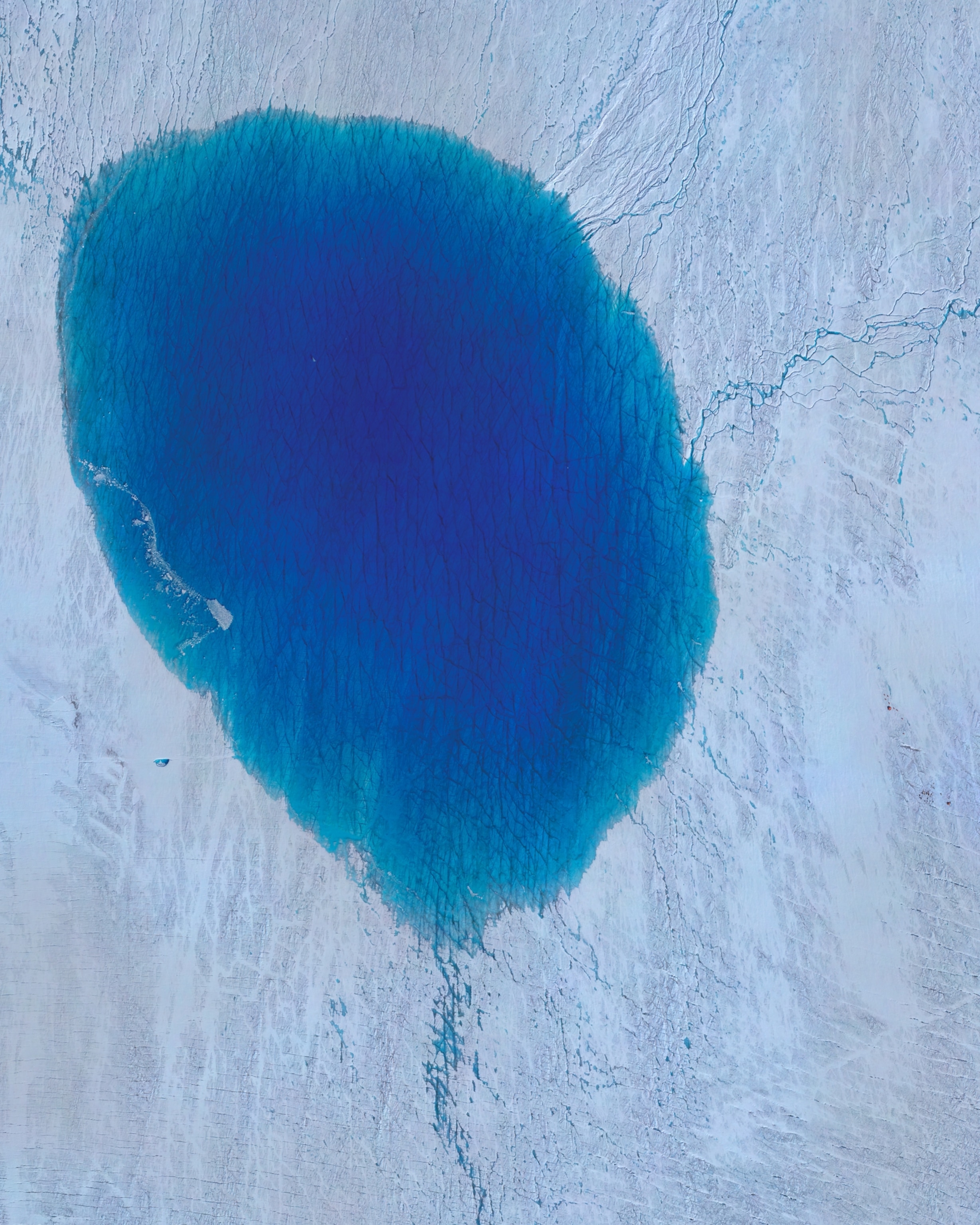

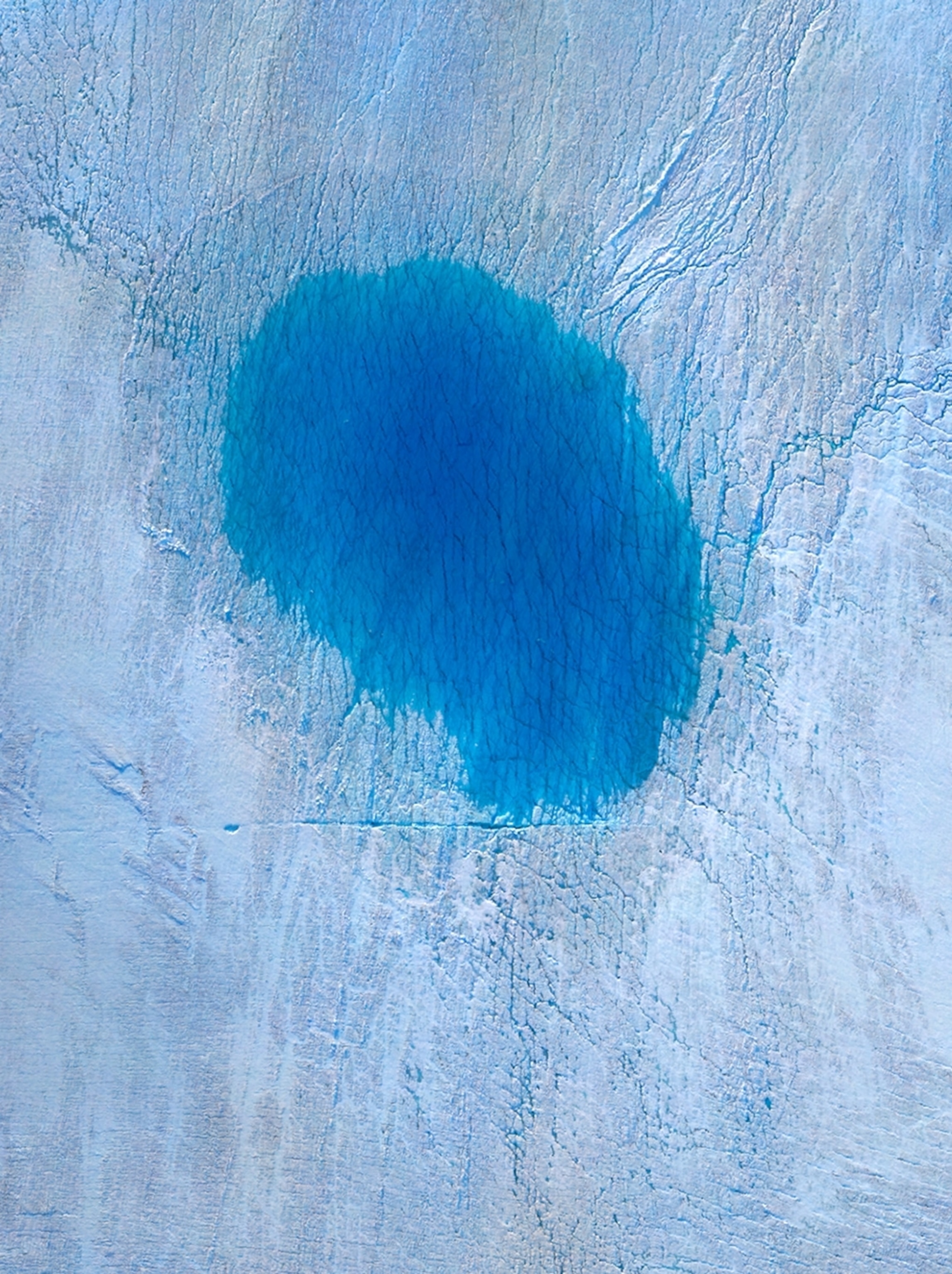

As an adult, I became a journalist whose beat is the environment. In a way, I’ve turned my youthful preoccupations into a profession. I’ve traveled to the Amazon to report on deforestation, to New Zealand to see the impacts of invasive species, and to Greenland to accompany scientists drilling through the melting ice sheet. I’ve also had kids. I watched with pride when they joined their school’s environmental club and recounted to them—perhaps once or twice too often—my memories of pulling recyclables from the trash in my school cafeteria.

I now live in New England, where April 22 can be a glorious day. The trees are starting to bud, the spring peepers are calling, the phoebes are building their nests. Every year on Earth Day, I try to go for a hike in the woods near my house. I look for tadpoles and admire the spring ephemerals. And every year I grow more worried about the planet’s future.

If, on the first Earth Day, instead of watching Walter Cronkite on CBS, you’d tuned in to NBC, you would have heard one of that network’s anchors, Frank Blair, deliver a curious message. Toward the end of his report on the festivities, Blair noted that a government scientist named J. Murray Mitchell had issued an “awesome Earth Day warning.” Blair summarized the warning this way: Unless something were done to reduce air pollution, it would “create a greenhouse effect” that would warm the entire planet. Eventually the effect would be enough to melt the Arctic ice cap and flood “vast areas of the world.”

Probably not many viewers had any idea what Blair was talking about. In 1970 the term “global warming” had yet to be coined. Scientists knew that certain gases, including carbon dioxide, trap heat near the surface of the Earth; this had been understood since the Victorian era. But only a few had tried to calculate what the impact of burning fossil fuels would be. Climate modeling was in its infancy.

The models have since become much more sophisticated. And though many Americans still willfully refuse to accept the science of climate change, we all now live with its consequences.

The perennial Arctic ice cap—the sea ice that persists through winter and summer—is wasting away. Over the past half century it has shrunk by more than a million square miles. Sea levels are rising ever faster, largely thanks to accelerating melt from Greenland and Antarctica.

Increasingly, low-lying coastal cities in the United States are experiencing what’s known as sunny-day flooding, when all it takes is a high tide to send water gushing into the streets. According to projections from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, this sort of flooding will, a few decades from now, be the norm in cities such as Miami, Florida, and Charleston, South Carolina. By 2050, Norfolk, Virginia, is expected to experience high-tide flooding nearly half the days of the year.

And the kind of sea-level rise that will make life difficult in places like Norfolk is apt to make it impossible in places like the Marshall Islands and the Maldives. A recent study by American and Dutch researchers predicted that by the middle of this century, most atolls would be uninhabitable.

Flooding, meanwhile, is just one of the unfortunate consequences of fiddling with the planet’s thermostat. A warmer world is also racked by deeper droughts, fiercer storms, and more erratic monsoons. It’s a world where the wildfire season lasts longer and the blazes grow bigger and more intense.

Before 1970, megafires—fires that consume at least 100,000 acres—were rare in the United States. In the past decade, there have been dozens. In the summer of 2019, forest fire burned through more than 17 million acres in Siberia; this is an area nearly as large as Ireland. Smoke engulfed the region in a sickly haze and prompted health officials to advise residents of cities such as Krasnoyarsk to venture outside only if absolutely necessary. In late 2019 and early 2020, fires in Australia ravaged tens of millions of acres.

And that’s not all. Land degradation, coral bleaching, increasingly deadly heat waves, the expansion of marine dead zones—these are all happening now. I could go on and on listing the dangerous impacts of climate change, but then you might stop reading. My point is: We’re already seeing a great deal of damage, and it’s increasing year by year.

In 2070, when Earth Day turns 100, what will the Earth look like? This clearly depends on how much carbon we emit between now and then. (Just in the roughly 10 minutes it takes you to read this article, more than a half million tons of CO2 will be added to the atmosphere.) But to a disturbing extent, the future has already been written.

The first Earth Day was such a grassroots explosion that just about every media outlet wanted in on it. The Today show ran a whole week of special programming with the theme “New World or No World.” The show’s host, Hugh Downs, opened the week with this assessment: “Our Mother Earth is rotting with the residue of our good life. Our oceans are dying, our air is poisoned.”

“Do we have the will to turn our way of life upside down?—because that is what it is going to take,” Downs continued. “Or do we go on breeding, demanding more and more power, more of everything until we suffocate or die of plague or famine? Probably within the next century, possibly within the next couple of decades?”

In 1970 the planet was home to 3.7 billion people. There were some 200 million cars and trucks on the road; oil consumption was around 45 million barrels a day. That year, people collectively raised about 36 million tons of pork and 14 million tons of poultry, and harvested around 65 million metric tons of seafood.

Today there are nearly eight billion people and some 1.5 billion vehicles on the planet. Global oil consumption has more than doubled, as has power use. Pork consumption per capita has almost doubled, poultry consumption has nearly quadrupled. The global wild fish catch has increased by about half, even as overfishing has made fish harder to find. In other words, to borrow from Downs, we kept “demanding more and more.”

And yet people haven’t just survived; by most measures, they’ve thrived. Globally, life expectancy has increased from 59 years in 1970 to 72 years today. Even as the number of people on the planet has more than doubled, the number of people living in extreme poverty has been cut in half.

With hindsight, it’s easy see why Downs’s predictions were off. They failed to anticipate breakthroughs such as the green revolution, which spread new plant varieties and farming techniques and allowed increases in grain production over the past 50 years to outpace increases in population. In 1970 aquaculture barely existed. It now produces some hundred million metric tons of fish annually.

And Earth Day itself spurred change. Just seven months after millions of Americans took to the streets, the Environmental Protection Agency was created. Many of the country’s major environmental laws, including the Clean Water Act, the Endangered Species Act, and key amendments to the Clean Air Act, were approved by Congress within the next few years. These, in turn, led to the development of technologies, like scrubbers to clean the stack gases of power plants.

Even if we were to start cutting emissions today, the problem of climate change would continue to grow.

So why not assume that the same sorts of innovations—both technological and social—will spare us from a future immiserated by global warming? Certainly, I believe that there will be many breakthroughs between now and 2070. In the course of my reporting, I’ve driven cars that emit only water vapor as a waste product and seen machines that suck carbon dioxide out of the air. Inventions I can’t begin to imagine are doubtless on the way.

Unfortunately, though, climate change is a special kind of problem. Carbon dioxide hangs around in the atmosphere for centuries, even millennia. This means that even if we were to start cutting emissions today, the amount of CO2 in the atmosphere and the problem of climate change would continue to grow—just as the water level in a bathtub will continue to rise if you reduce but don’t shut off the flow from the tap. Earth will keep warming until we shut down emissions completely.

Meanwhile, we’ve yet to experience the full effects of the CO2 we’ve already emitted, mostly because it takes the huge oceans a long time to warm up in response to a given level of CO2. Average global temperatures have risen by about 1 degree Celsius (nearly 2 degrees Fahrenheit) since the 1880s, but owing to the time lag in the system, scientists estimate we’re committed to another half a degree or so Celsius (almost a degree Fahrenheit). As far as climate change is concerned, it’s always later than it seems.

How hot can it get before truly catastrophic changes are set in motion? (To cite one such potential change, were the Greenland ice sheet to melt away entirely, global sea levels would rise by about 20 feet.) Scientists warn that the threshold is probably about 2 degrees Celsius warmer than preindustrial times and perhaps even 1.5 degrees. Because temperatures already have risen about a degree and there’s another half a degree of “commitment,” we’re all but assured of passing 1.5 degrees. To keep temperatures under the 2-degree threshold, global emissions would have to drop by at least half over the next few decades, and all the way to zero by 2070 or so.

In theory, this is possible. Most—perhaps all—of the world’s fossil fuel infrastructure could be replaced by solar cells, wind turbines, and nuclear power plants. In practice, the tremendous boom in wind and solar that’s under way has not reduced our use of fossil fuels, because we keep demanding more and more energy. Even as the impacts of climate change become increasingly vivid, global emissions continue to rise. In 2019 they hit a new record of 43.1 billion metric tons. In Madrid in December, the United Nations climate negotiations ended once again in failure. If current trends continue, the world in 2070 will be a very different and much more dangerous place—one in which flooding, drought, fire, and probably also climate-related unrest will have forced millions of people from their homes.

Last year I wrote an obituary for a snail named George. George was about an inch long, with a gray body and a shell ringed in beige and brown. He’d spent his entire 14-year life quietly slithering around a terrarium in Honolulu. Researchers with Hawaii’s Division of Forestry and Wildlife had tried to find him a mate—George was a hermaphrodite but needed a partner to reproduce—and when they failed, they concluded he was probably the last of his kind, Achatinella apexfulva. A few days after George’s death, the division posted a eulogy under the heading “Farewell to a Beloved Snail … and a Species.”

Achatinella apexfulva joined a long list of extinctions since 1970. Others include the Colombian grebe, the Yunnan lake newt, the golden toad, the Southern gastric brooding frog, and the Saudi gazelle. Several hundred more species, such as the Yangtze River dolphin, are listed as “possibly extinct” by the International Union for Conservation of Nature. Most of them have not been seen for decades. The list covers only the species the IUCN has assessed—probably less than 2 percent of what’s out there. Extinction rates today are hundreds—for some groups, probably thousands—of times higher than they’ve been throughout most of geologic history.

And for every species teetering on the edge of oblivion, many more seem headed in that direction. According to the WWF’s Living Planet Report, the wild populations of mammals, birds, fish, reptiles, and amphibians have shrunk, on average, by 60 percent since the first Earth Day. (This doesn’t mean the total number of individual animals has dropped by 60 percent, because losses to small populations have a disproportionate impact on the figures; still, it’s a pretty grim statistic.)

A study published last fall found that there are now some three billion fewer birds in North America than there were 50 years ago, a decline of nearly 30 percent, and that some of the steepest drops have been among such common species as blackbirds and sparrows.

The big boom in renewable energy has not reduced our use of fossil fuels, because we keep demanding more and more energy.

“It’s staggering,” said Ken Rosenberg, a conservation scientist at Cornell Lab of Ornithology and the lead author of the study. Insects too appear to be dwindling. A study by European researchers published in 2017 found that the biomass of flying insects in a set of German protected areas had dropped by an alarming 76 percent just in the previous three decades.

If people are doing better than they were in 1970, clearly the opposite is true for most other creatures. The two trends can be traced to the same source. To feed, house, and provide energy for our own growing population, we’ve appropriated ever more of the world’s resources for ourselves. People have significantly altered something like three-quarters of the ice-free land on Earth. More than 85 percent of the world’s wetland area has been lost. All around the globe, farming has become more intensive, with more acres of monoculture and fewer of the weedy patches that used to provide sustenance for native insects, which in turn provide sustenance for birds. Even in places like national parks, suitable habitat for many species is shrinking because of factors such as climate change and invasive species.

“Wild creatures, like men, must have a place to live,” the late American conservationist Rachel Carson observed.

The great question for the next 50 years is whether the trends of the past 50 years will continue. People could collectively decide to reduce their impact on other species by, for example, putting an end to deforestation and reconnecting fragmented habitats. But, as with cutting carbon emissions, there’s no evidence that this is going to happen. On the contrary, tropical deforestation rates over the past few years have surged.

A report last year by the international body charged with monitoring ecosystems and biodiversity warned that humanity could not continue to thrive while so many other creatures suffered. “Nature is essential for human existence,” it noted. About three-quarters of all food crops, for example, rely on pollinators—birds, bats, or in the vast majority of cases, insects. Humans can’t easily live without those animals.

“The essential, interconnected web of life on Earth is getting smaller and increasingly frayed,” said ecologist Josef Settele of Germany’s Helmholtz Centre for Environmental Research, and a cochair of the report.

Of course, Settele and his colleagues may be wrong, and for the same reason Downs was. Perhaps people will perfect pollen-carrying drones. (They’re already being tested.) Perhaps we’ll also figure out ways to deal with rising sea levels and fiercer storms and deeper droughts. Perhaps new, genetically engineered crops will allow us to continue to feed a growing population even as the world warms. Perhaps we’ll find “the interconnected web of life” isn’t essential to human existence after all.

To some, this may seem like a happy outcome. To my mind, it’s an even scarier possibility. It would mean we could continue indefinitely along on our current path—altering the atmosphere, draining wetlands, emptying the oceans, and clearing the skies of life. Having freed ourselves from nature, we would find ourselves more and more alone, except perhaps for our insect drones.