Why weren’t we ready for this virus?

For decades the world has ignored pandemic predictions from the experts. Maybe the coronavirus will change that.

In the first weeks of the coronavirus pandemic, I couldn’t bear to read about our collective early missteps. Not only because the implicit rebuke felt futile—what was the point in knowing that the grim reality we were living could have been avoided?—but because, in my case, it also felt deeply personal. Each article I read about missing the warning signs of a devastating new virus reminded me that decades ago, scientists had been worrying about that very thing, and a few science journalists were writing about their alarm. I was one of them.

When I started researching this in 1990, the term “emerging viruses” had just been coined by a young virologist, Stephen Morse. He would become the main character in my book A Dancing Matrix, published three years later. I described him then as an assistant professor straight out of central casting: earnest, bespectacled, a man who lived life largely in the mind.

Morse and other scientists were identifying conditions—climate change, massive urbanization, the proximity of humans to farm or forest animals that were viral reservoirs—that could unleash microbes never before seen in humans and therefore unusually lethal. They were warning that, thanks to an increasingly global economy, the ease of international air travel, and the movement of refugees due to famines and wars, these killer pathogens could easily spread around the world. Sound familiar?

“The single biggest threat to man’s continued dominance on the planet is the virus.” I used that searing quote from Joshua Lederberg, a molecular biologist who won a Nobel Prize for his work on bacteria, in my book’s introduction. Back then I thought Lederberg might have been a bit melodramatic. Now his quote strikes me as terrifyingly prescient.

When the U.S. death toll from COVID-19 had not quite reached a thousand and New Yorkers like me were three days into our governor’s stay-at-home order, I phoned Morse to see how he was holding up. He teaches epidemiology at Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health and is now in the age range of those most vulnerable to the worst ravages of the coronavirus. (I am too.) He and his wife were self-quarantining in their Manhattan apartment, just a few miles from mine.

“I’m discouraged, yes, to find we’re not better prepared after all this, and we’re still deep in denial,” Morse said. He went straight to a favorite quote, from management guru Peter Drucker, who once was asked, “What is the worst mistake you could make?” His answer, according to Morse: “To be prematurely right.”

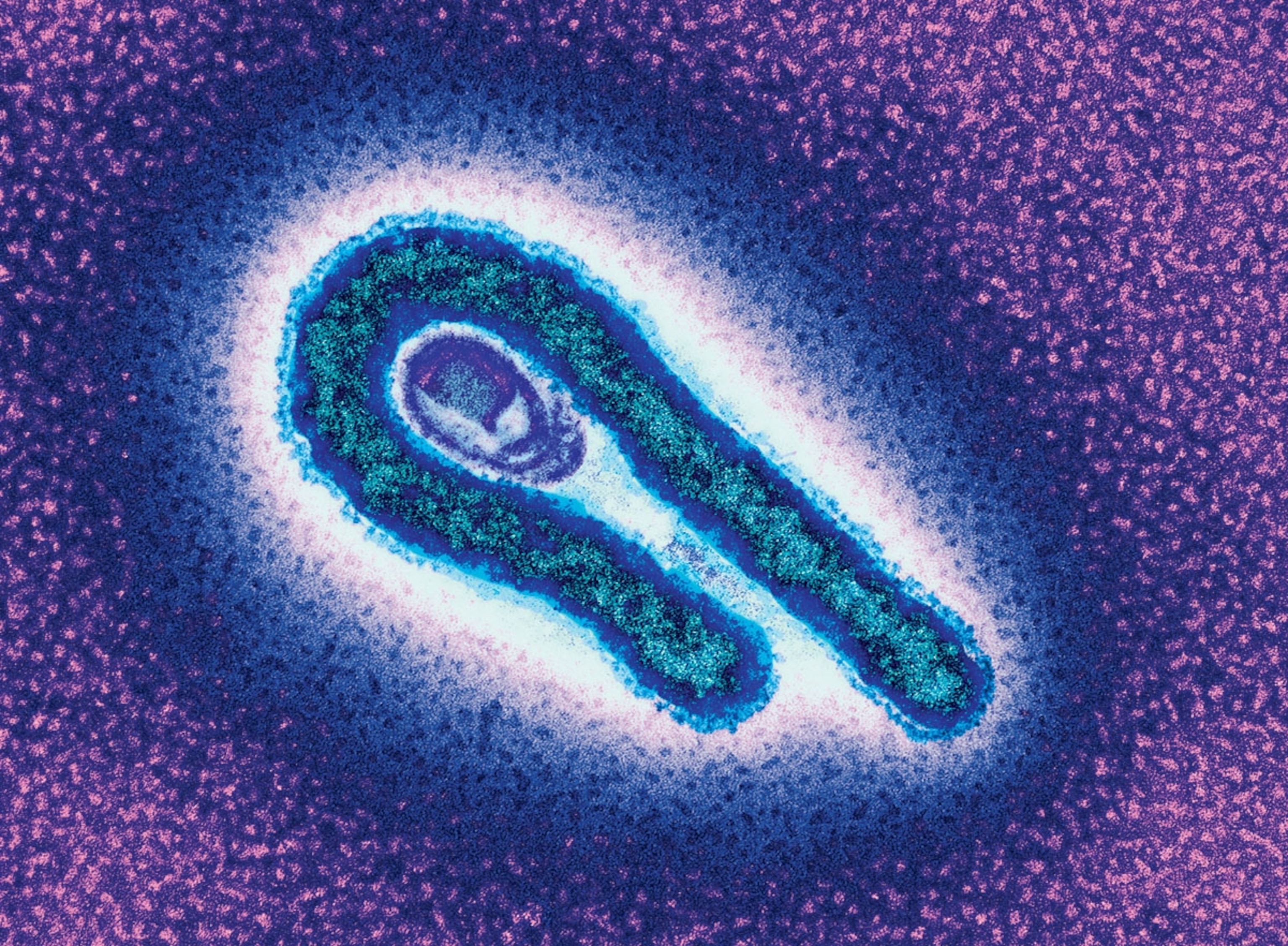

SARS in 2003 pretty much stayed in Asia, MERS in 2012 didn’t really leave the Middle East, Ebola (virus shown above) in 2014 was mostly a West African scourge. As we kept watching ourselves dodge a bullet, it was easy to attribute susceptibility in other countries to behaviors that didn’t exist in ours.

Morse and I weren’t right, prematurely or otherwise. Nobody was. When I was asked on my book tour what the next pandemic would be, I said most of my expert sources believed it would be influenza. “I never liked lists,” Morse told me during our call; he said he always knew the next plague could come from anywhere. But in the early 1990s he and his colleagues tended to focus on influenza, so I did too. Maybe that was a mistake; if the next pandemic was going to be influenza, that didn’t strike most as especially shattering. The flu? People get that every year. We have a vaccine for that.

So maybe the warnings were too easy to dismiss as “just the flu” or as the catastrophic thinking of one overwrought writer. But other journalists were writing similar books, and some of them were huge best sellers, like The Hot Zone, by Richard Preston, and The Coming Plague, by Laurie Garrett, which came out the year after mine. (Other more recent books include Spillover, David Quammen’s follow-up to a story on zoonotic diseases that he wrote for National Geographic in 2007.) All of us described the same dire scenarios, the same war games, the same cries of being woefully unprepared. Why wasn’t any of that enough?

The late Edwin Kilbourne might have had something to say about that. A leading influenza vaccine researcher, Kilbourne was gaunt and goateed; in my book I described him as a cross between Pete Seeger and Jonas Salk. At a conference in the mid-1980s, Kilbourne invented a scenario about a fictitious nightmare virus with qualities that would make it the most contagious, most lethal, and most difficult to control. He called it “maximally malignant (monster) virus,” or MMMV. As Kilbourne described it, among MMMV’s other nefarious attributes, it would be transmitted through the air like influenza, would be environmentally stable like polio, and would insert its own genes directly into the host’s nucleus like HIV.

The novel coronavirus isn’t Kilbourne’s ghoulish MMMV, but it does have a lot of its scariest properties. It’s transmitted through the air, replicates in the lower respiratory tract, and is thought to last for days on countertops. In addition, people can have mild or asymptomatic cases, meaning that even though they are infectious, they often feel healthy enough to walk around, go to work, and cough on us. In that way it’s even worse than influenza and even harder to contain.

But just as Morse said he’s never liked “Most Likely to Endanger Us” lists, Kilbourne told me 30 years ago that he’d conjured MMMV for illustrative rather than predictive purposes. “With viruses, in which only a few changes can make a huge difference in the way the microbes behave, trying to predict the paths of evolution and emergence can be a treacherous affair,” he warned.

In countries like mine, we might have become inured to the threat of a global pandemic because we saw so many “This Is the Big One” threats flaming out, confined to regions that felt comfortably remote. Except for AIDS, raging epidemics have tended not to go global: SARS in 2003 pretty much stayed in Asia, MERS in 2012 didn’t really leave the Middle East, Ebola in 2014 was mostly a West African scourge. As we kept watching ourselves dodge a bullet, it was easy to attribute susceptibility in other countries to behaviors that didn’t exist in ours. Most of us didn’t ride camels, didn’t eat monkeys, didn’t handle live bats or civet cats in the marketplace.

This “othering” of the threat has, in many ways, been our undoing all along. In rereading my book recently, I found a sentence that highlights the persistence of this shameful attitude. “Ask a field virologist what constitutes an epidemic worth looking into,” I wrote, “and he’ll answer with characteristic cynicism, ‘The death of one white person.’ ”

I’ve turned my file drawers inside out looking for an old notebook that might contain the name of one such “field virologist,” to no avail. But even without that crucial confirmation, I believe in the essential point of that haunting sentence. We’ve been “othering” away the safety of our species for decades. We’re doing it still, fostering an official and personal complacency that ultimately brought humanity to its knees.

What’s it been like to watch the coronavirus pandemic unfold nearly three decades after I wrote that a pandemic would unfold in pretty much this way? It’s induced a strange vertigo, to be honest. It’s also sparked an unfamiliar kind of solipsism, enough to make me wonder: If I had made the case for surveillance and preparation more forcefully back then—that is, if I had written a better book—would we be here now?

Still, there’s something enlightening about reading the book’s stories about the epidemics from the last century, when new viruses kept emerging, raging through a population, and eventually dying out. But never since the 1918-19 influenza pandemic has any been on this scale, and never with this ferocious mixture of transmissibility and lethality. We almost learned the right lessons in the 1990s, and then we ignored them; maybe this time, with prediction having become reality, the lessons will stick.