They tried to steal this American's citizenship. He fought back—and won.

Wong Kim Ark battled nativists all the way to the Supreme Court. His 1898 victory established the definition of U.S. citizenship in a landmark decision.

In 1897 the 14th Amendment was barely three decades old when it was put to the test, thanks to Wong Kim Ark. Ratified in 1868 in the aftermath of the Civil War, this addition to the U.S. Constitution defines U.S. citizenship in Section 1: “All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside.” But anti-immigrant forces challenged its straightforward language. Wong sued for his rights under the 14th Amendment, and his case would go all the way to the Supreme Court.

Nativist fears

Nativist attitudes were prevalent throughout the United States in the 19th century, and in the West they targeted Chinese immigrants. California passed a series of laws from the 1850s through the 1870s discriminating against Chinese residents; at the federal level, laws were introduced trying to exclude Chinese immigrants from entering the country. Some even passed Congress but were vetoed by President Rutherford B. Hayes, who was trying to balance foreign relations and domestic politics.

(The bloody history of anti-Asian violence in the West.)

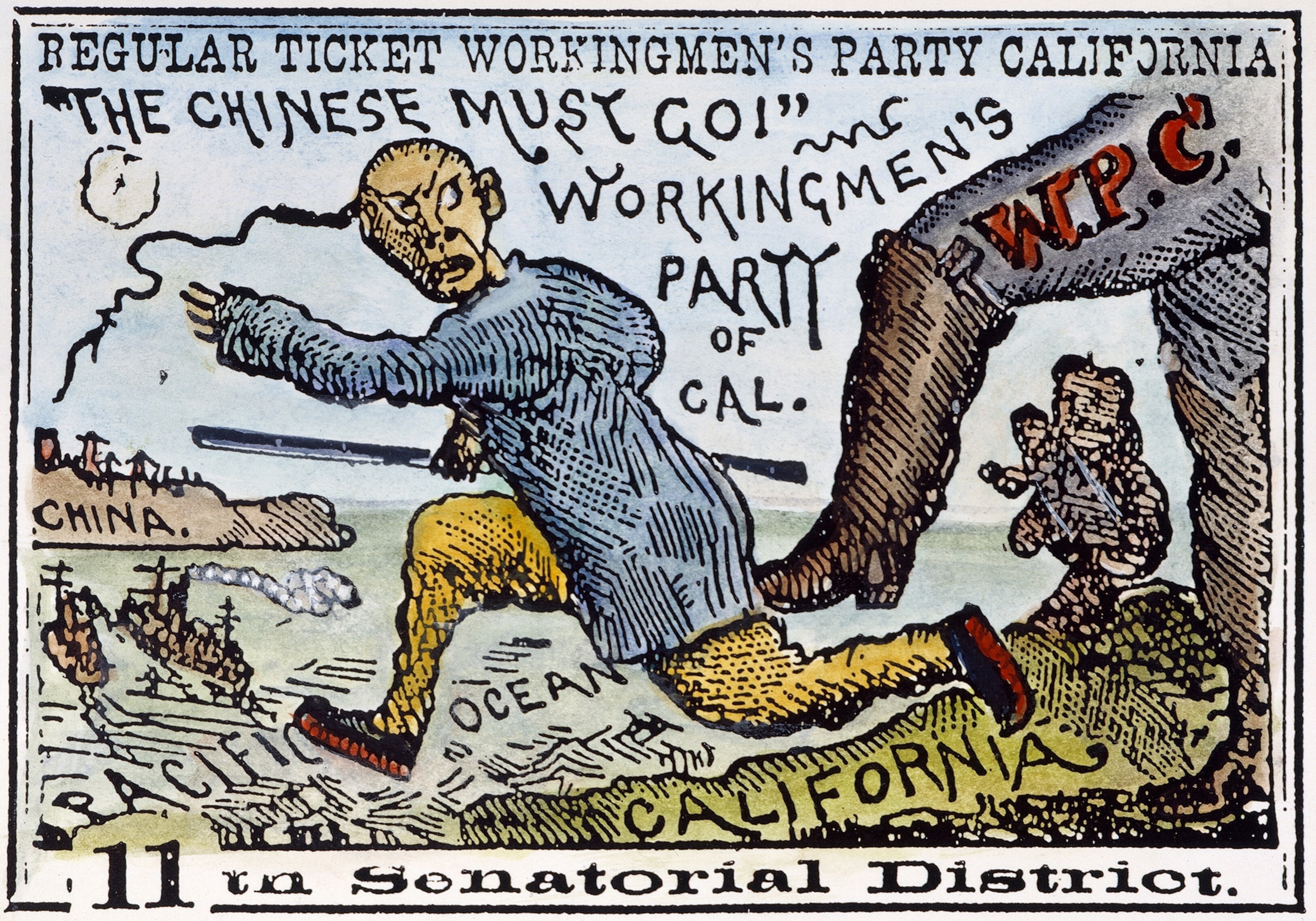

The Panic of 1873 had shifted the federal government’s balance to U.S. politics and strengthened the power of nativists in the West. They loudly blamed Chinese laborers for widespread unemployment and wage cuts. Denis Kearney and his Workingmen’s Party of California united behind the slogan “The Chinese Must Go!” Chinese communities came under serious threats of violence; 19 Chinese people were killed in a race massacre in Los Angeles in 1871. In San Francisco buildings were destroyed in Chinatown and Chinese graves desecrated.

Anti-Chinese prejudice culminated in the passage of the Chinese Exclusion Act, which was signed into law by President Chester Arthur in 1882. It denied naturalization to Chinese immigrants already in the United States and denied entry of new workers from China for 10 years. Under this law, Chinese people traveling in or out of the United States had to carry a certificate that identified their working status—laborer, scholar, diplomat, or merchant. In 1888 the Scott Act was passed, which barred reentry to the United States from China, even for long-term legal residents. In 1892 the Geary Act followed, which renewed exclusion for 10 more years and became permanent in 1902 (The exclusion acts would finally be repealed in 1943).

Born in the U.S.A.

Wong Kim Ark was born in San Francisco, California, in either 1871 or 1873. His parents, Wong Si Ping and Wee Lee, immigrated from China and settled in California as part of a large wave of immigration from China to the American West in the mid-19th century.

Many of the first Chinese immigrants worked in California’s gold mines, then on farms, and in factories. Chinese laborers were integral in building railroads in the U.S. Like later immigrants, Wong Si Ping and Wee Lee were entrepreneurs. They opened a store on Sacramento Street in San Francisco, lived in the apartment above it, and started a family. Despite having lived in California for nearly two decades, Wong’s parents could not become U.S. citizens because of their foreign birth. Qualifications for naturalized citizenship were established under the Naturalization Act of 1790, which said that an immigrant could only become a citizen if they were “a free white person, who shall have resided within the limits and under the jurisdiction of the United States for the term of two years . . . and making proof . . . that he is a person of good character.”

(What can the transcontinental railroad teach us about anti-Asian racism?)

In the 1880s there were not many native-born Chinese Americans in the United States. Some estimates place the figure as low as one percent of the total population. Wong was in a minority, having been born and raised in San Francisco. Unlike his merchant father, he worked as a cook. When his parents decided to return to China in 1890, Wong traveled with them, stayed a few months, but ultimately returned to the United States.

During that brief first stay in China, Wong married and conceived a child with his bride. He returned to California before his son was born. Living in the United States while having family back in China was not uncommon for the time. Some scholars estimate that as many 40 percent of Chinese American men were married to women who still lived in Asia. Parents often negotiated these marriages, and Wong’s parents may have used their son’s age and his earning potential as qualities to attract prospective brides in China.

Proof of citizenship

No reentry

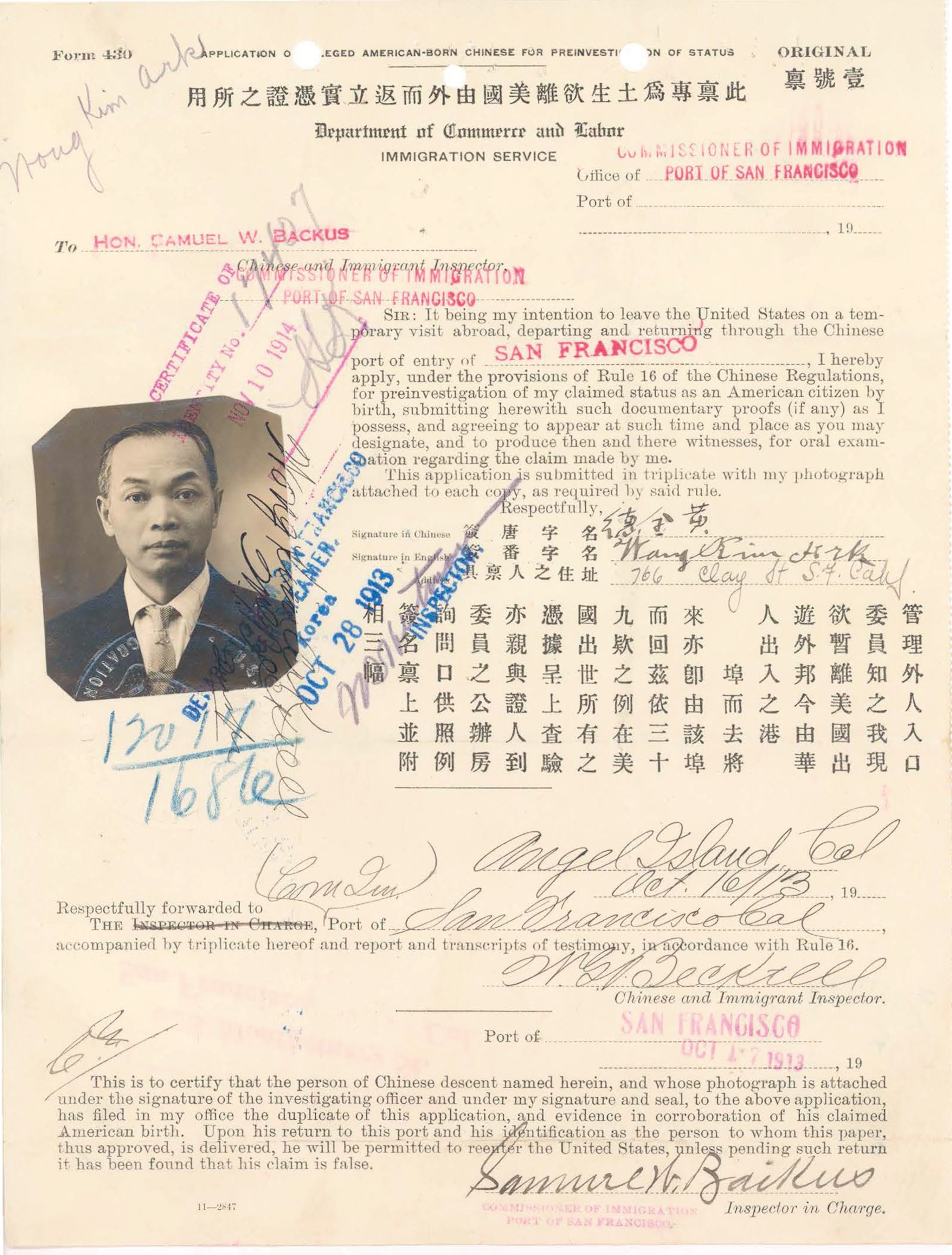

In November 1894 Wong returned to Asia to visit his wife, young son, and parents. Because of the Chinese Exclusion Act, he had to obtain the proper documentation to secure his return to the United States—a photograph of himself and the affidavit of three white men that he was “known to us” and had been born in the United States.

Wong sailed back to San Francisco aboard the Coptic in summer 1895 but was denied entry by John Wise, the customs collector and self-described “zealous opponent of Chinese immigration.” Despite having the proper legal documentation, Wong was detained offshore aboard steamships in San Francisco Bay for five months.

Chinese Americans had been fighting for decades to protect their civil rights. In San Francisco they had established an aid organization named the Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association but known as the Six Companies. Their lawyers took up Wong’s case and filed a writ of habeas corpus, meaning that his rights as a citizen, granted to him by jus soli (Latin for “right of the soil”), were being violated. Because he was a natural-born citizen, provisions of the Chinese Exclusion Act did not apply to him. Wong was released on bond while his case was heard.

Backed by anti-Chinese forces in San Francisco, U.S. Solicitor General Holmes Conrad decided to challenge the Six Companies and their defense of Wong. Based on the principle of jus sanguinis (meaning “right of blood,”) Conrad’s case argued that Wong’s parentage, not his place of birth, determined his status; therefore, he could not be a U.S. citizen because his parents were Chinese and that made Wong“also a Chinese person, and subject of the emperor of China.”

United States v. Wong Kim Ark made its way to the Supreme Court, where each side was argued before eight justices (the ninth, Justice McKenna, was not sitting on the court when arguments were made). In 1898 Justice Horace Gray wrote the 6-2 majority opinion, which found “the American citizenship which Wong Kim Ark acquired by birth within the United States has not been lost or taken away by anything happening since his birth.” Gray pointed out that there were exceptions to this rule for children of “foreign sovereigns or their ministers, . . . or of enemies within and during a hostile occupation . . . [or] of members of the Indian tribes owing direct allegiance to their several tribes.” In a direct refutation of Conrad’s argument, the majority pointed out that many children of “English, Scotch, Irish, German, or other European parentage” would lose their U.S. citizenship if their parents’ status were the determining factor.

The fourteenth amendment of the Constitution . . . contemplates two sources of citizenship, and two only,—birth and naturalization. Citizenship by naturalization can only be acquired by naturalization under the authority and in the forms of law. But citizenship by birth is established by the mere fact of birth . . . Every person born in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, becomes at once a citizen of the United States, and needs no naturalization.Justice Horace Gray, Majority Opinion, United States v. Wong Kim Ark

American family

After the Supreme Court’s decision Wong Kim Ark continued to live and work in the United States but still visited his family in China where his wife and sons lived. The pair had three more sons together—all conceived on return visits by their father. Despite the court ruling in Wong’s favor, anti-Chinese discrimination persisted. Every time Wong visited China, he still had to fill out so-called “departure papers” swearing to the fact that he was a U.S. citizen to be guaranteed readmission.

(How Ellis Island shepherded millions of immigrants into America.)

Angel Island

Passing through Angel Island Immigration Station in San Francisco Bay, Wong’s sons all joined their father in California at different times, and he served as a witness on their behalf. Only the youngest, Wong Yook Jim, would make a life for himself in the United States, even after his father returned to China permanently in the 1930s at age 62. Wong Yook Jim found work across the country as a waiter, and during World War II, like many other U.S. citizens, served his country in the armed forces.