American Cool: You’ll Know It When You See It

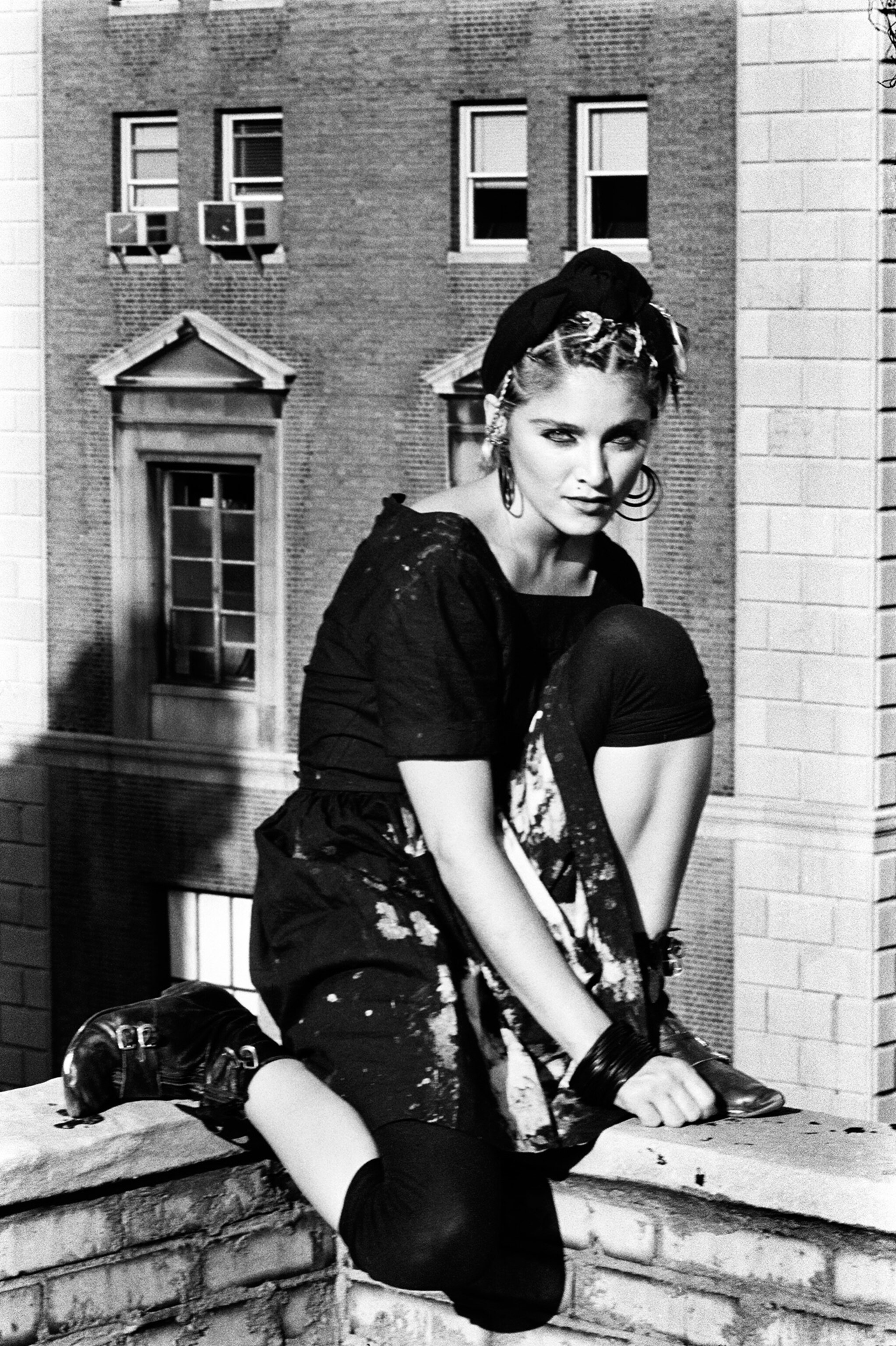

What does it mean to say someone is cool? Sounds like a simple question, doesn’t it? Everyone knows it when they see it, but defining what exactly makes someone cool is trickier than it seems. Is it the aloof restraint Miles Davis maintained while belting out brilliant tunes on the trumpet? Or the boundary-pushing spectacles and outfits Madonna put on? Maybe it’s the raw emotion Johnny Cash poured into his lyrics and performances?

When Joel Dinerstein and Frank H. Goodyear III curated American Cool, an exhibit that’s up now at the National Portrait Gallery, they tried to identify exactly what makes for a legacy of cool.

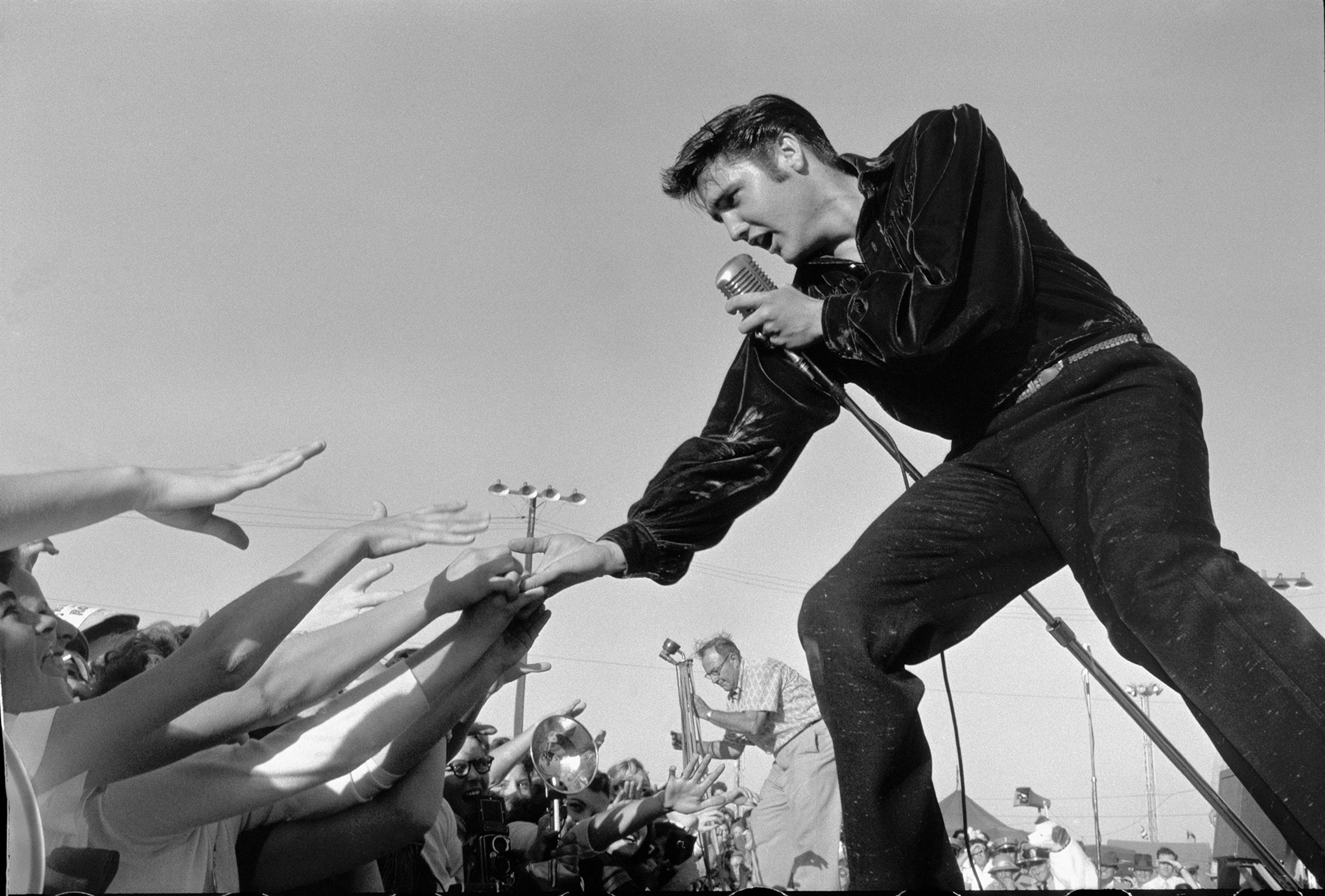

Dinerstein and Goodyear traced the evolution of cool, from its birth in the swinging jazz nightclubs of the 1940s and ‘50s, when “cool” meant staying calm and composed during dizzying social change. When restaurants refused to serve James Baldwin in the early 1950s, he wrote “there is not a Negro alive who does not have this rage in his blood.” Yet, rather than boil over, Baldwin chose stoic resistance. In the 1960s and ‘70s, cool took on clear anti-establishment connotations. By borrowing images from advertising and pop culture, Andy Warhol rejected traditional ideas about what makes art art. Bob Dylan protested the Vietnam War with poetic lyrics. In the 1980s, square became the new cool, with kids flocking to preppy styles and politics.

Although answering the question “What exactly is it that makes someone cool?” is a decidedly uncool exercise in semantics, it’s a fascinating one nonetheless. Dinerstein and Goodyear created a rubric with the common threads they found across the decades. For a person to pass the test of cool, he or she had to have at least three of the following: 1) possessed an original artistic vision, 2) rebelled or transgressed in a given historical moment, 3) been recognized as an icon, and 4) had a cultural legacy of at least 10 years. On top of that, the curators looked harder to measure variables, like charisma, self-possession, and just not caring what other people think. If Dinerstein had to sum up how he would describe who is cool, he’d say, “the successful rebels of American culture.” In other words, the people whose ideas or art transgressed traditional values, but whose ideas and art became accepted by society.

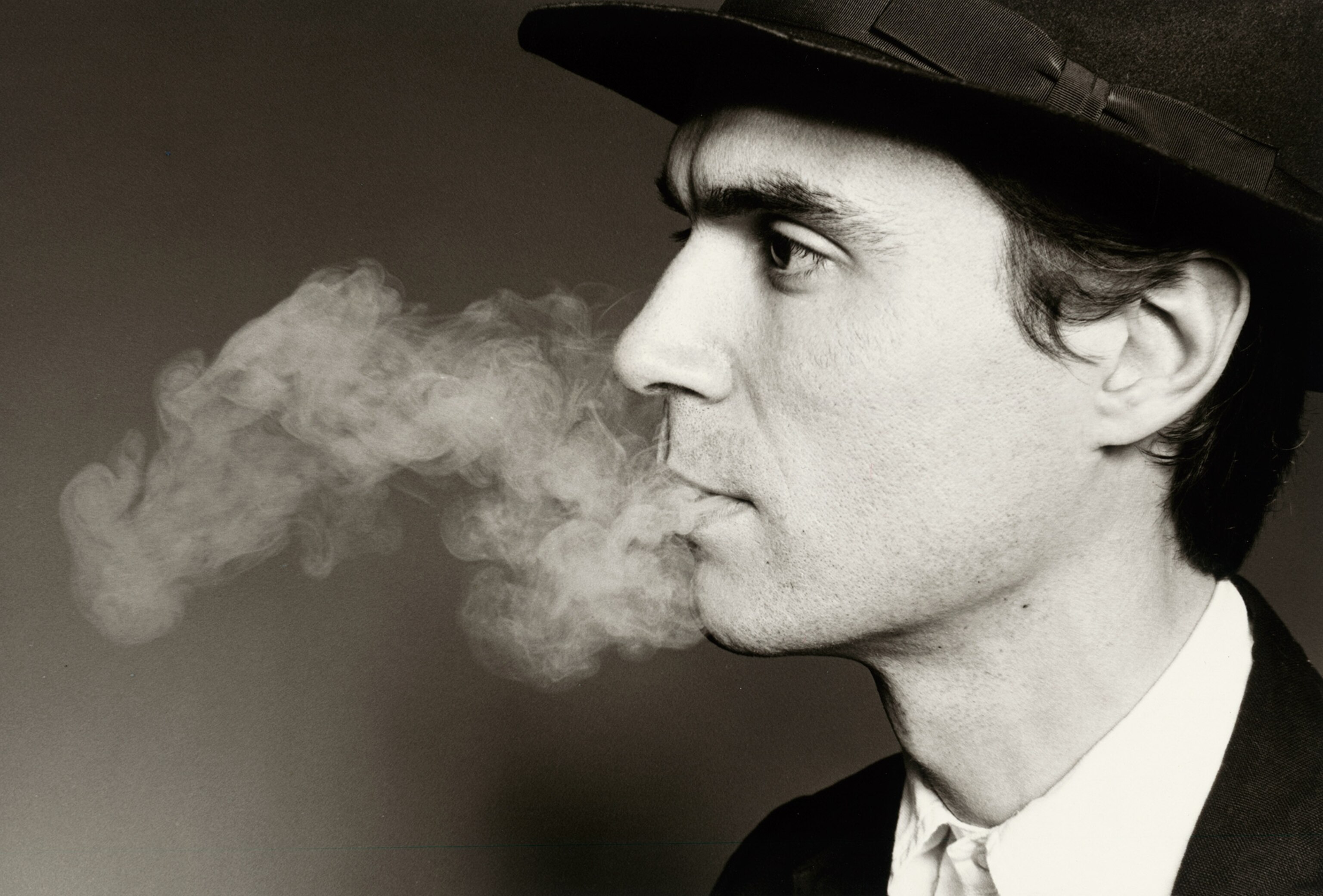

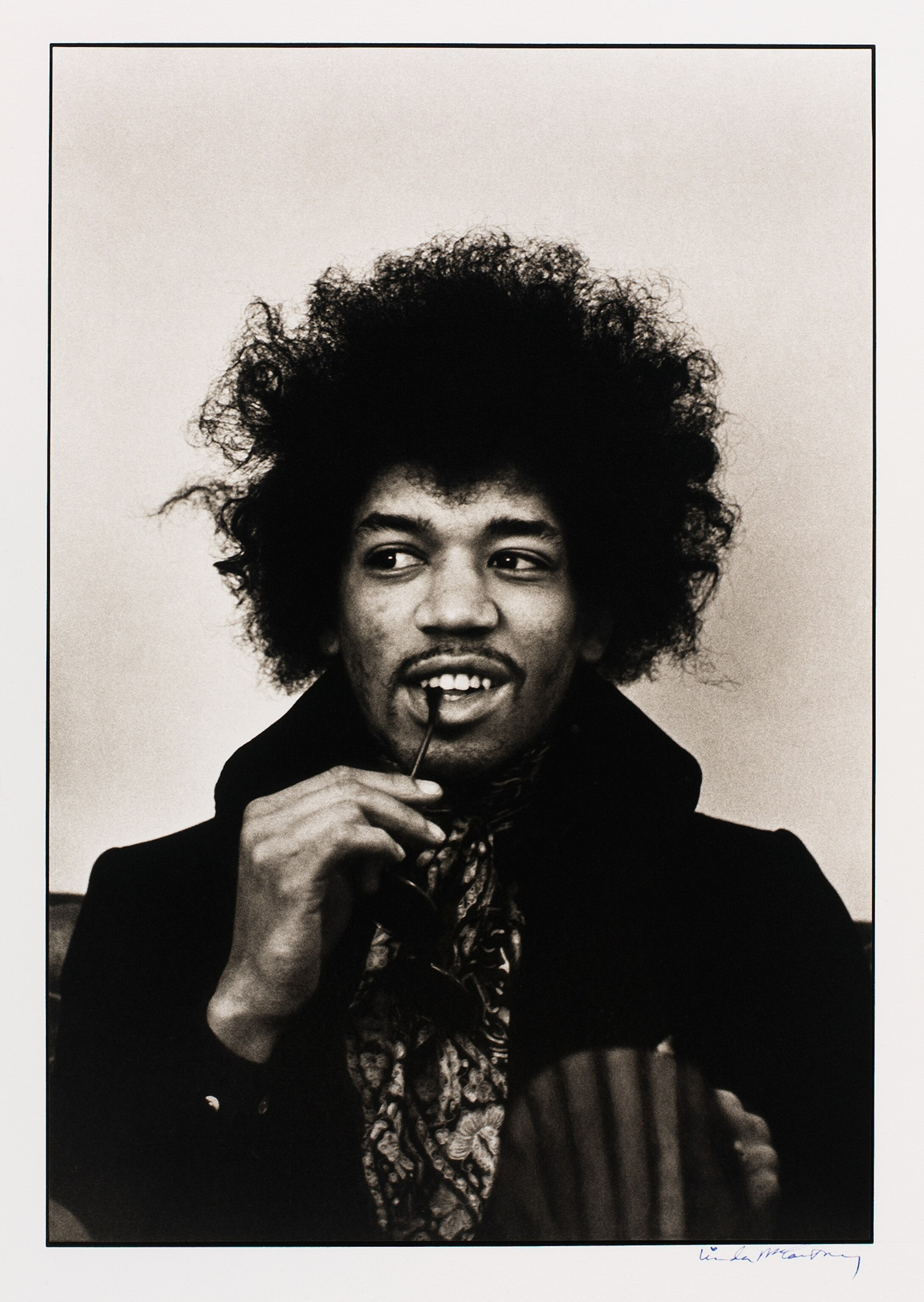

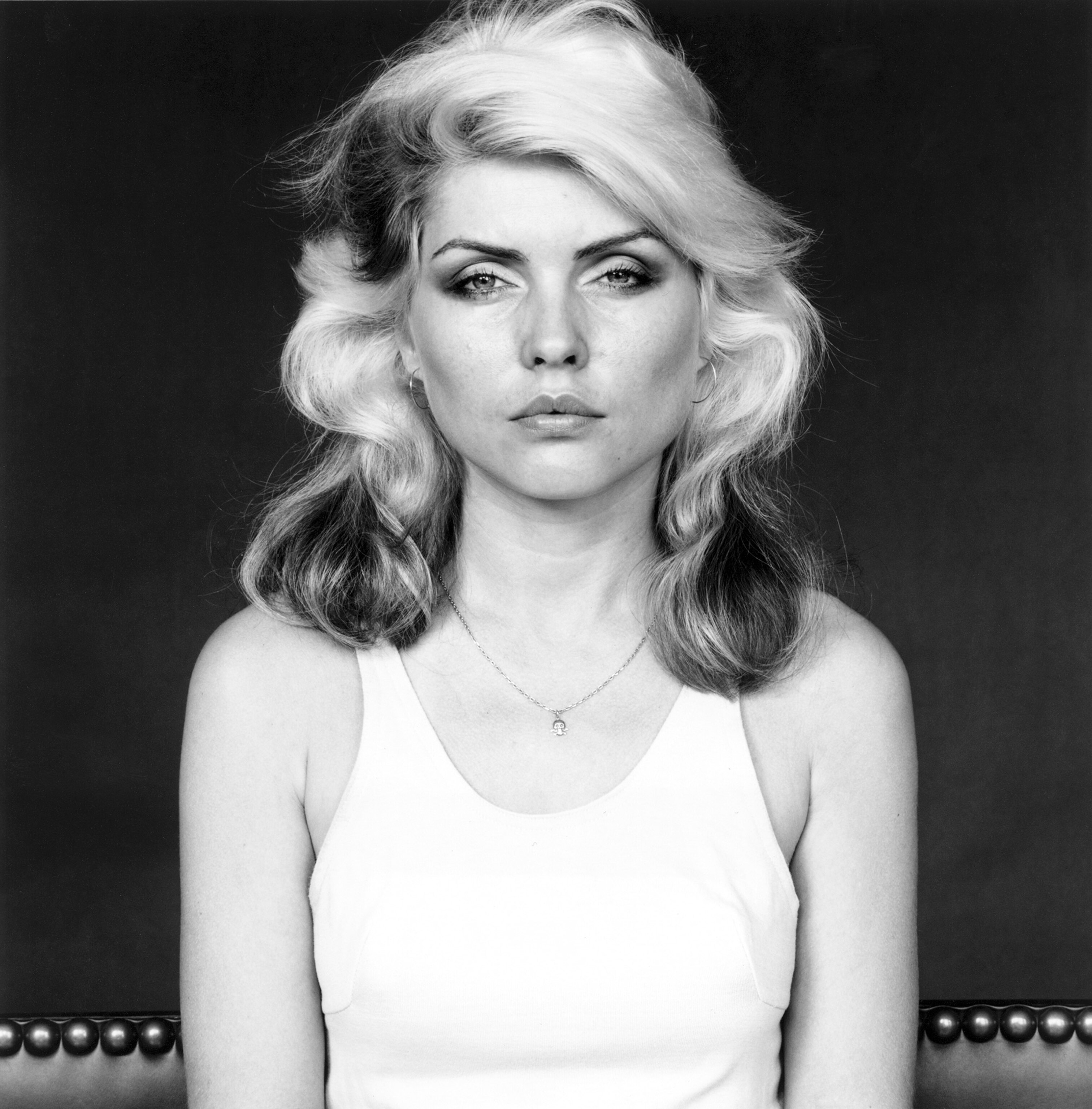

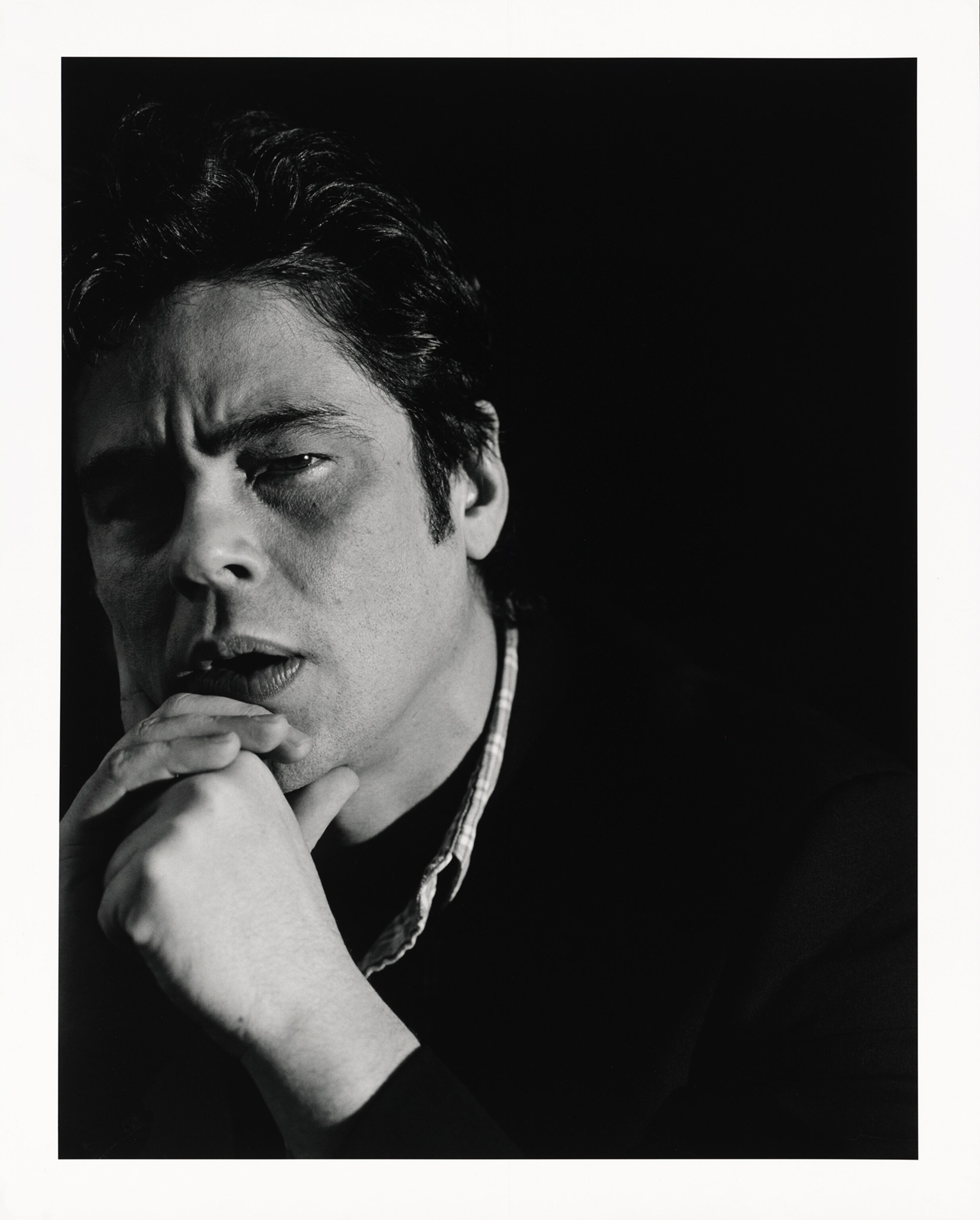

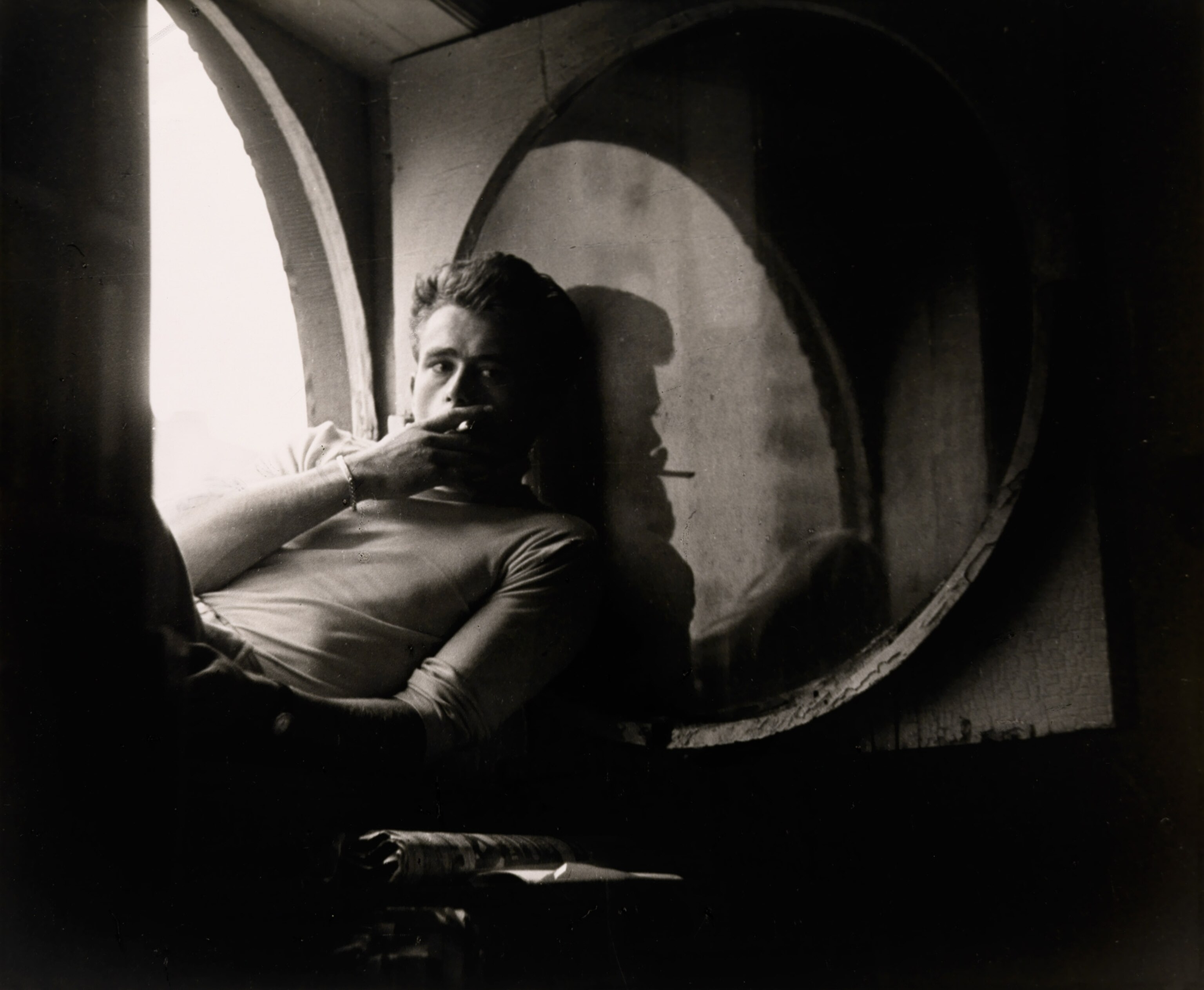

And of course, the person had to look cool in photographs. Why? “Photography makes cool possible,” Dinerstein says, and it has the “power to transform a person into an icon.” In the exhibition catalog, Goodyear writes that James Dean became famous not for his first starring role in East of Eden, but for the moody portraits of him by Dennis Stock that ran in Life magazine. Those portraits helped establish the idea of Dean as a troubled loner. And it is these images, rather than his film career, that has made Dean a lasting icon in American society. Although many people today may not have seen Dean in Rebel without a Cause or East of Eden, they are likely to know the famous portraits by Roy Schatt of him smoldering through a cloud of smoke.

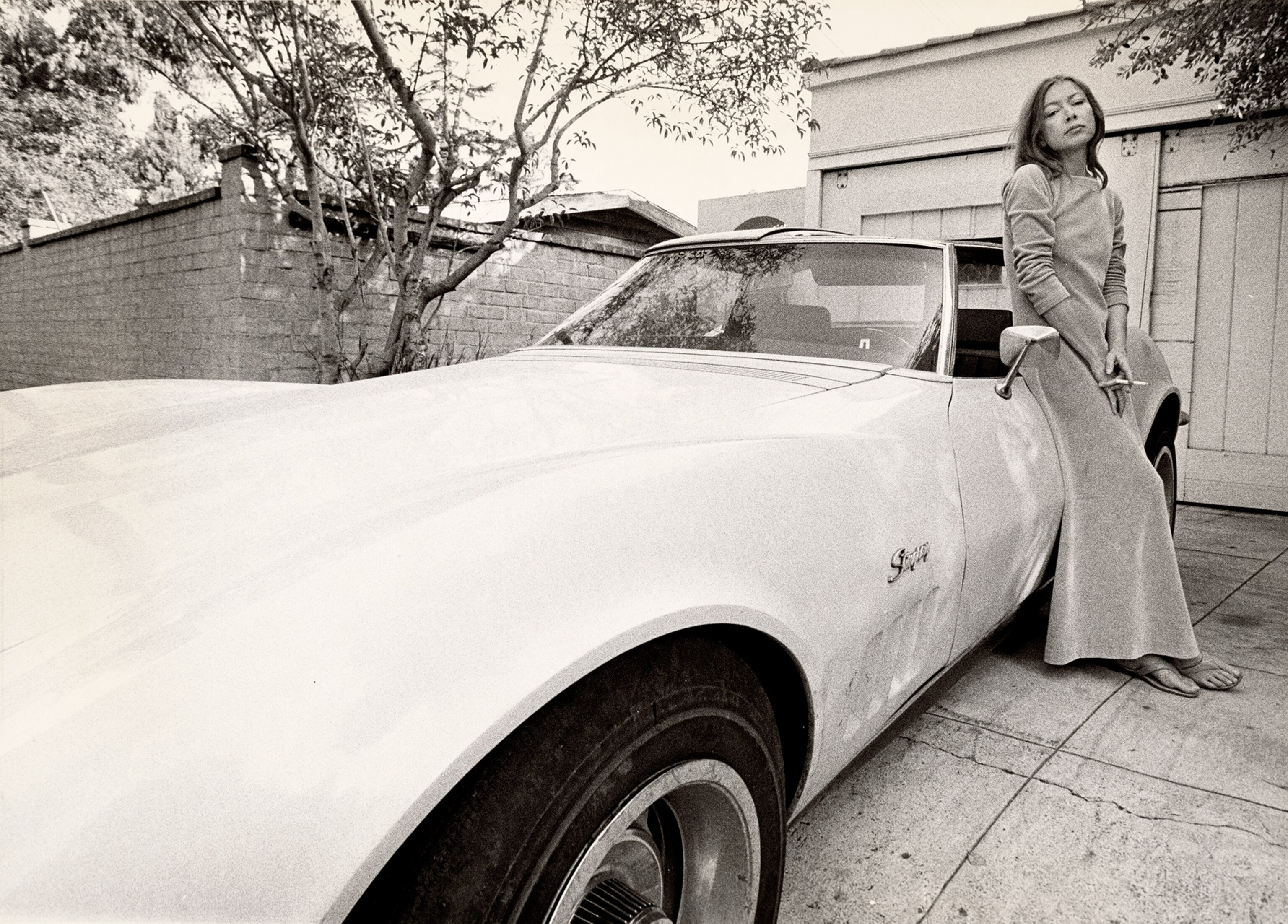

The 100 people Dinerstein and Goodyear crowned “cool” now have their pictures hanging in matching frames from the walls of the National Portrait Gallery, tidily organized by decade. Though many of the photographs are beautiful (an image of a luminous Billie Holiday stands out in my mind), the exhibit feels too polite, too much like a text to truly portray this group of rule-breakers and rebels who stood up to discrimination, wars, and tradition. And although the exhibit isn’t groundbreaking enough to pass its own test of cool, the history of a concept we all think we know is cool enough to make a visit worthwhile.

American Cool is on display through September 7, 2014 at the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, D.C.