Christmas Brings Millions of Filipinos the Joy of Homecoming

Every December overseas workers come back to the Philippines. We captured their reunions.

MANILA, PHILIPPINES — When Bernardita Lopez first left home to be a domestic worker in Hong Kong, she clung to one piece of advice from the Philippine government seminar for departing Filipinos: When you enter the airport, don’t look over your shoulder. Just keep heading straight. Moving forward will be hard enough, so don’t look back.

It’s the week before Christmas, and Bernardita, filled with anticipation, isn’t looking back—she’s arrived at Manila’s Ninoy Aquino International Airport, where her two brothers, Allen and Jepoy, are waiting to pick her up. As she emerges from immigration, she—and a throng of other jostling, excited homecomers—is greeted by carolers singing “Joy to the World.” On the ride home she gazes out the window—it’s 2 a.m., and Manila’s Christmas lights are all aglow.

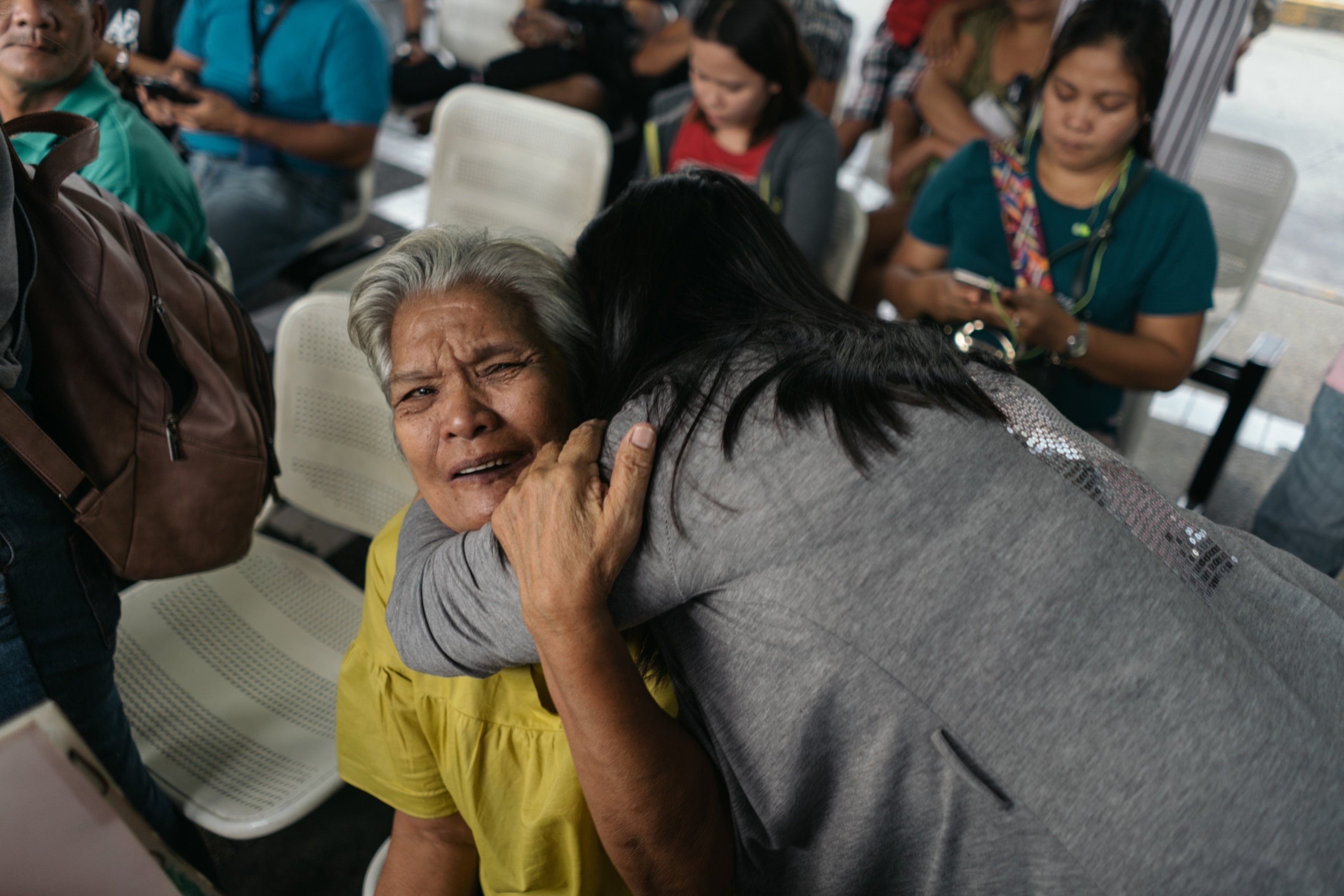

Each December about a million people land in Manila, many of them returning to savor precious time with family and friends. This year is no different: The airport is filled with family members crowding the display screens as they wait for the plane bringing their long absent mothers, fathers, sons, and daughters home. In the sea of welcome signs, a child holds up a homemade one: WELCOME BACK, MAMA! (Here's one mother's journey as an overseas Filipino worker.)

The diaspora, which former President Gloria Macapagal Arroyo called “our greatest export,” is home again.

About 6,000 people leave the island nation each day to seek opportunities across the globe. Filipino seafarers make up about a third of the world’s mariners. One-third of all foreign-born registered nurses in the United States come from the Philippines, and nearly one in four Filipino-born women employed in the U.S. is a registered nurse. Around the world Filipinos are singers, caregivers, laborers, domestic workers, engineers.

But when they come home at Christmastime, they’re bagong bayani—modern-day heroes. As one plane after another touches down in Manila, passengers burst into applause. They’re home—home to their warm, tropical Christmas, to Noche Buena (the Christmas Eve feast), to late-night ballads sung on karaoke machines. The returning heroes celebrate and are celebrated across the country—until once again it comes time to leave.

One in ten Filipinos now lives abroad. “Abroad” is a loaded word to Filipinos. Abroad is the people you miss, but it’s also your hope for the future. For the Lopez family, abroad is part of the fabric of their family. Bernardita is a registered nurse, but she’s worked as a domestic helper in Hong Kong for more than three years. Her brother Allen is a seafarer waiting to get on a ship. Her half-sister, Sane, went to Canada as a caregiver, and the youngest, Bernardita’s 20-year-old brother Jepoy, is studying to become a nurse; he too plans to go abroad to work. Their mother, Cristina, was babysitting in Canada where she died suddenly of a heart attack in May 2017.

Christmas in the Philippines is a rich mix of homegrown and colonial traditions, a time of hope and expectation. The season begins in September, and as December draws closer, Manila gets brighter. Parols, colorful lanterns symbolizing the star of Bethlehem, dot windows and streets. Churches are packed for the simbang gabi, a series of nine Masses that begin before dawn and culminate in the Christmas Eve crescendo of gift giving, singing, and feasting over lechon, or suckling pig. It’s believed that completing all nine Masses affords one a wish.

Bernardita’s first Christmas home was in December 2015. But the joy of that reunion was marred by the death of their father, Alberto, a jeepney driver, on Christmas Eve at the age of 56. This Christmas the family gathers around to open the balikbayan box she had sent home earlier. Balikbayan boxes are large cardboard boxes filled with anything from chocolate bars and sneakers to body lotion and Spam. (Balik means “return,” and bayan means “country.”)

Children grow up excited for the balikbayan box. They squabble over hand-me-downs from relatives abroad and take turns to see whose foot will fit which shoe. Years ago when ours was opened, I remember exclaiming, “It smells like America!”—long before I ever set foot outside the Philippines. In Bernardita’s home the mood is no different. The box sits in the middle of the room bearing a big red label from the courier that says: “We like to move it.”

In a church just north of Manila, a Christmas tree is hung with folded pieces of paper. They contain hand-written wishes that loved ones living abroad may be home again soon.

“My friends always say that going home to the Philippines is like pulling a thorn from your skin because you’re finally coming home,” Bernardita says. “But when you have to leave again, it’s like the thorn goes back in.”