George Steinmetz’s Eye From the Sky

What is it like strapping yourself into the equivalent of a leaf blower, getting a running start, then taking off into the air with a camera in your hand?

“You have 180-degree horizontal and vertical visibility and you’re going about 27 or 28 miles per hour. You don’t need a plexiglass windscreen in front of you. It’s kind of like you’re flying around on the edge of a spoon. For pictures, it’s the bomb.”

The first time George Steinmetz took his flying machine (a motorized paraglider manufactured in Germany, to be precise) out for an assignment, it was in the Sahara Desert to photograph a volcanic crater about eight miles in diameter, which required he fly up to almost 6,000 feet. “I took off at sunrise, just when there was enough light to see, and I just went full throttle for about an hour until I basically ran out of gas,” he tells me during a recent phone call. “I was really nervous up there … It was really quite petrifying. And I thought wait a minute, I’m up here, I’m really determined to get this picture, so I better take the f-ing picture! If you’re going to die, at least get the picture first. Don’t die for nothing!”

He found that once he focused on taking pictures, he stopped thinking about dying and calmed down. “When I get up there,” he says, “I find whenever I get into a situation, taking pictures is very helpful because it helps me think about things I can control.”

I couldn’t help but wonder whether such moments are a source of exhilaration on the level of the thrill-seeking seen in adventure sports, or an inhibition.

Neither. “I fly for pictures,” he says. “If I don’t have a camera I don’t go flying. If I can get the place better from a hill, or a helicopter, or a plane I’ll do that. There are some kinds pictures you can’t get any other way…I am a cold-blooded pragmatist in the field.”

Steinmetz has had his share of unscheduled landings—17 stitches after hitting a tree on takeoff in China; run-ins with the locals—stone-throwing women in a village in Yemen; ridicule—a cadre of Sudanese soldiers hired to protect him instead laughing, “We were hired to protect you and you are trying to kill yourself!”; and even arrest—the much-publicized incident near a Kansas cattle feed lot for the May issue of National Geographic.

But these are far outweighed by the moments of beauty, wonder, and satisfaction from capturing scenes that few—other than birds— get to see. He describes a moment in the Sahara desert. He had been shadowing a caravan of several hundred camels for several days, trying to get the shot he wanted, until one morning he decided to go for another fly.

“I looked on the horizon and there was another caravan coming the opposite way. So I was able to get these two enormous caravans passing each other. I had been flying over the camels for days and they didn’t care about me at all,” (Steinmetz tells me that sometimes the sound of his paraglider is enough to get some of the more flighty animals running, a fact which he sometimes, very judiciously, might use to his advantage) “I was able to get this really rare moment. That kind of thing doesn’t exist anymore, the caravans are kind of dying. I was able to get this retina to brain shock where you are seeing something really fabulous that you’ve never seen before. As a photographer I live for those moments.”

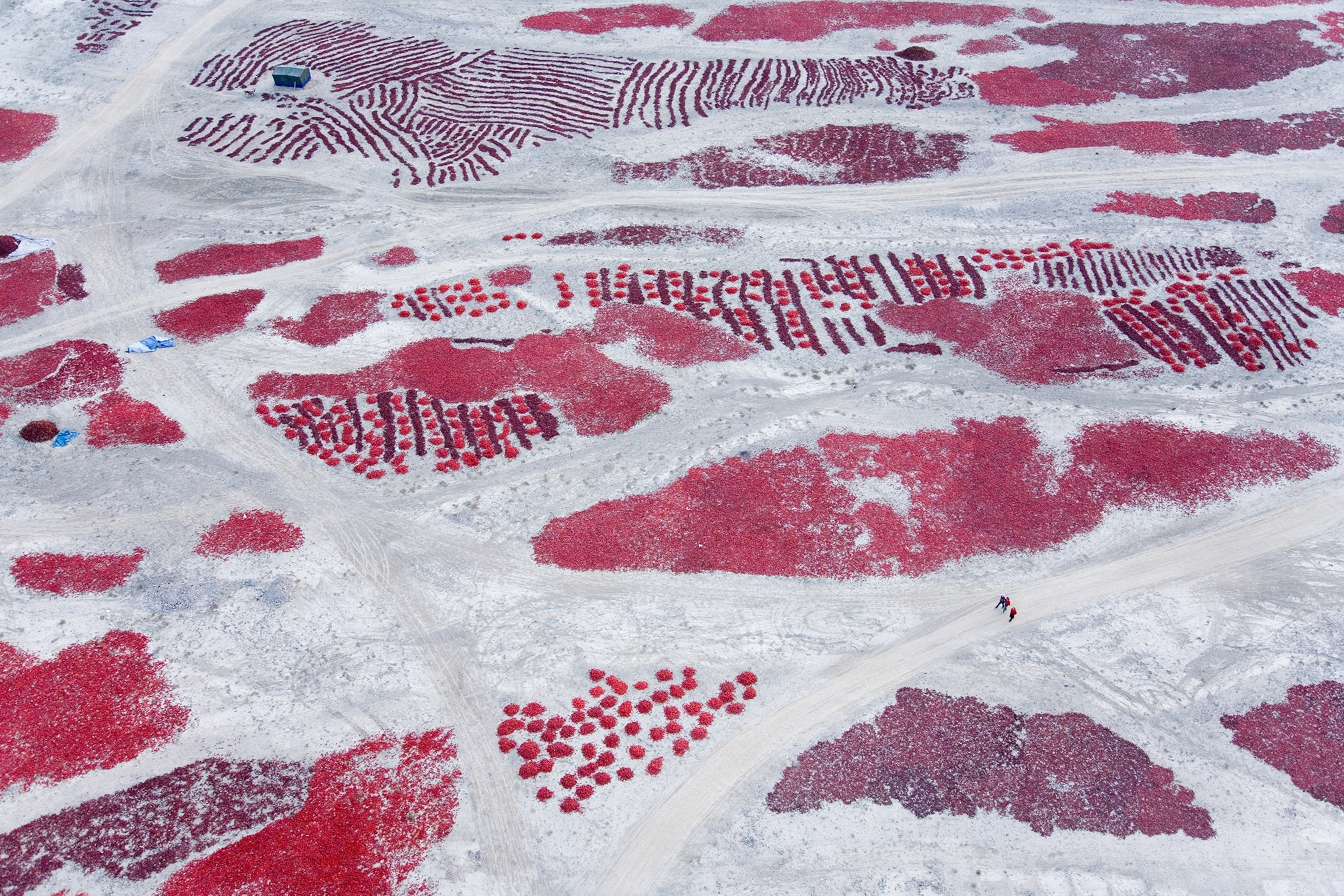

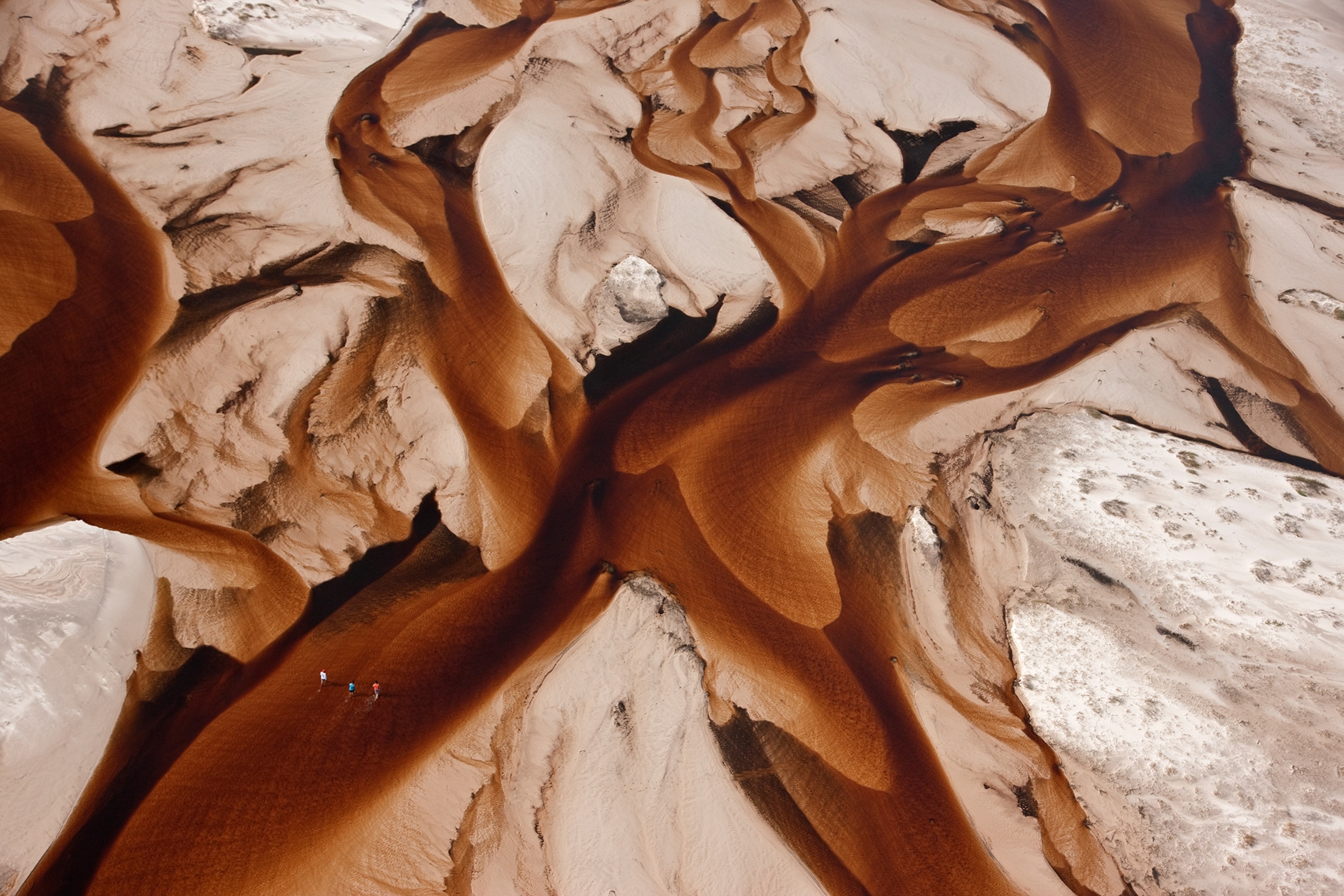

The middle altitude of 100-500 feet, just below helicopter range, is where Steinmetz prefers to hang out: “You are seeing [the land] more obliquely, so you see the 3-D relationship. It’s the perfect mix where I can see the gross pattern—the infinite skyline or the mountains in the distance but also people and what they are doing.” He describes it as “street photography from the sky.”

Steinmetz strongly believes his pictures must tell a story of what’s happening below, either of the people or the landscape. Having studied geophysics at Stanford, “I have a pretty good understanding of the fundamentals of geomorphology, the forces that shape the earth, and in the air I’ll try to find the position in the sky and the time of day that renders that most cleanly and aesthetically. I want to take really fabulous pictures but [have] those pictures decode the landscape for the viewer. You want to look at spatial relationships—to have the tongue of the glacier in the foreground and you see it winding back into the mountains, and the light is just right. A picture has to tell a story.”

“What I love to do is take pictures of things that people haven’t ever seen before,” he continues. “If I’m sitting next to someone on an airline and they open up the magazine and say “Wow look at that!” that makes my day.”

Listen to Steinmetz talk about what inspires him as a photographer. You can also learn more about Steinmetz on his website.