Why Iceland wants its medieval skulls back

Crania from a Nordic 'golden age' sit in a Harvard museum basement, and now researchers on both sides of the Atlantic want to reunite them with their bodies.

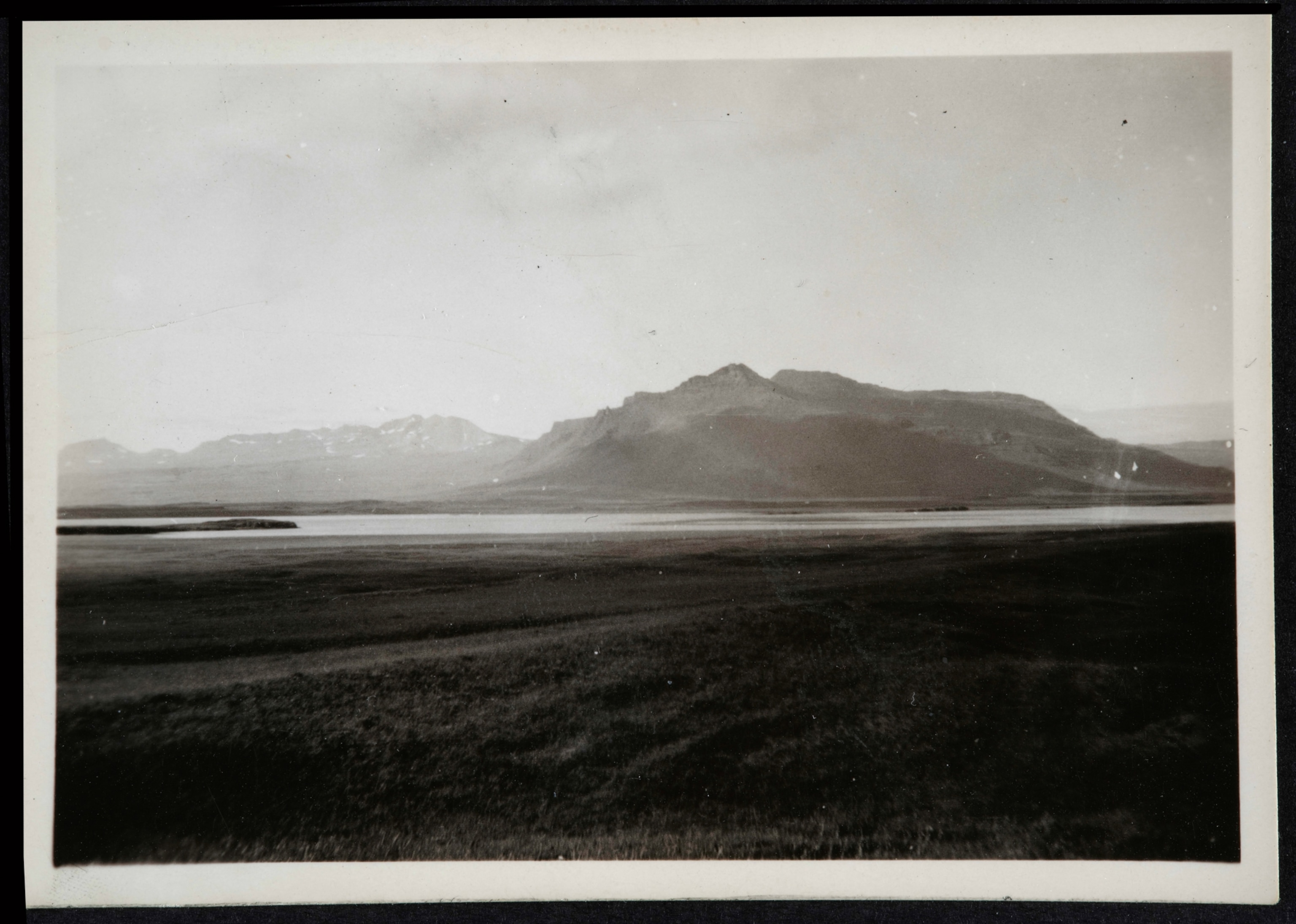

For nearly four centuries until around A.D. 1600, a community of Icelanders on the west coast buried their dead away from the mainland on the tiny island of Haffjarðarey. Centuries later, the relentless waves and rising sea levels that tugged at Haffjarðarey’s shores began to expose bones eroding from the island cemetery.

In 1945, that cemetery became the focus of what may have been the newly independent Republic of Iceland’s first emergency archaeology mission: to locate and excavate any remains of medieval Icelanders left on Haffjarðarey before they washed away for good. By most scientific measures the mission was successful, with the skeletal remains of at least 50 individuals identified, excavated, and removed from the island for study.

But there was one problem: most of the excavated bodies were missing their skulls.

Those missing skulls sit today in cardboard boxes on steel storage shelves in Harvard’s Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, where they were once an addition to the university’s eugenics pursuits, representing the supposedly “pure” Nordic Icelandic race among the museum’s vast collection of human remains.

Are museums celebrating cultural heritage—or clinging to stolen treasure?

Now, there’s interest by researchers in both Iceland and the U.S. to reunite Harvard’s skulls from Haffjarðarey with the rest of their bodies, located today at the National Museum of Iceland in Reykjavik. It’s not only good science, archaeologists argue, but also the morally and ethically right thing to do. But will the skulls remain in Cambridge, Massachusetts, separated by the Atlantic and decades of twisting history?

‘Prime harvest’ or ‘shameful act’?

Forty years before Iceland’s first archaeologists arrived to dig on Haffjarðarey, the young anthropologist Vilhjálmur Stefánsson led a Harvard expedition to the island. While Danish law in 1905 did not allow grave robbing in their colony of Iceland, Stefánsson secured permission from a local minister to collect skulls “disinterred by the sea.”

For Harvard, with its growing eugenics collection, Iceland was a time capsule for the Nordic “golden age.” It had been settled and subsequently cut off from Europe, preserving its "perfect" people in isolation. Stefansson in particular wanted to study local teeth; he'd heard Icelanders never got cavities because of their fish-based diet.

The Harvard team’s “prime harvest” collected more than five dozen human skulls in what Icelandic newspaper Ísafold called at the time a “shameful act,” accusing the team of acting without permission and under the cover of night. Before growing outrage could prevent their export, Stefánsson shipped the bones in four large crates to Cambridge on a steamer. At the Peabody Museum, the skulls of the anonymous medieval Icelanders became known as the Hastings-Stefánsson collection, named for the anthropologist and his student John Hastings, who helped him collect the remains from the sands of Haffjarðarey.

More than a century later, in 2015, graduate student Sarah Hoffman decided to study the Hastings-Stefánsson collection and stumbled on the existence of the rest of the bodies in Iceland after reading a reference to them in a bioanthropology paper. Hoffman, now a University of Buffalo anthropologist, later connected with archaeologist Adam Netzer Zimmer and Joe Walser, curator of physical anthropology at the National Museum of Iceland, and she was finally able to reunite the skeletal assemblage—at least on paper—for her 2019 PhD thesis. Her research revealed Haffjarðarey is one of the largest medieval-era archaeological sites in Iceland, with bones uniquely well preserved by the island’s sandy soil.

A population separated by an ocean

The geographic separation of the bones make the anthropologist’s work difficult. From the loose teeth and skulls in Harvard’s collection, Hoffman could use isotopic analyses to understand what the individuals ate and where they came from, but answering simpler questions like sex eluded her.

“I wish [the bones] could all be in one spot, from an archaeological collections perspective,” Hoffman says. “It’s so much easier to look at everything as one cohesive population as opposed to two separated by an ocean.”

The Haffjarðarey skulls alone were plenty useful for the scientific questions that early 20th century Harvard anthropologists like Stefánsson’s mentor Earnest Hooton worked on: categorizing and ranking “races” based on cranial measurements for eugenics. But they’re insufficient for contemporary research that focuses on characterizing the health and demographics of past communities, says Walser. Science reasons aside, he and other Icelandic scholars feel the skulls from Haffjarðarey should be returned on moral and ethical grounds.

Iceland was originally settled by the Norse and Celts and later controlled by Denmark, and thus has no Indigenous population. To Walser, that means there isn’t the same political urgency to repatriate the skulls compared to situations where a history of colonial oppression and looting is clear.

“So, instead, it’s simply a question of respect to the body and burial,” he says. “Should heads be separate from their bodies? I think this complexity for me boils down to that it just doesn’t seem right.”

Gísli Pálsson, professor emeritus of anthropology at the University of Iceland, agrees that cases where remains were taken from indigenous communities should be highest priority for international repatriation, but notes that the Haffjarðarey skulls were still collected in a colonial context. “I think they should end up in Iceland,” he says. “This is Icelandic heritage.”

Bringing the skulls ‘home’

In 2016 the National Museum’s head of collections reached out to the Peabody to start an initial conversation about repatriating the Haffjarðarey skulls. Harvard’s repatriations office shut down the discussion, claiming the museum’s focus on complying with the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA) prevented them from considering international repatriation requests. Discouraged, the Icelanders gave up.

NAGPRA requires American universities and museums to inventory human remains and funerary objects associated with federally recognized tribes and repatriate them in a timely manner when requested. Despite cases where the university has been criticized for moving slowly, Harvard has repatriated 43% its collection of Native American ancestral remains since the act was passed in 1990 and doubled the size of its office last year. But there’s no U.S. legal requirement to repatriate remains not covered by NAGPRA or to comply with requests from outside the country.

Jane Pickering, director of the Peabody, acknowledges the museum was focused solely on NAGPRA in 2016, but said things are “very different” today. In 2021, Pickering formally apologized for the Peabody’s role in colonialism and harm done to Indigenous communities. Harvard now has a steering committee on human remains, and the Peabody approved two cases of international repatriation of ancestral remains just in the last year, Pickering notes.

Repatriating the heads of Haffjarðarey

So, what would happen if Iceland’s National Museum made a formal repatriation request to Harvard today? The Peabody would investigate the provenance of the remains—the complex circumstances under which Stefánsson took the skulls—asking hard questions. “In this case there was local opposition,” Pickering notes. “It may have been permitted and legal, but does that make it right?”

Walser is also concerned about the safety of the fragile bones and whether the ethical imperative to return the remains outweighs the inherent risk of transporting them. Then it would be time to deal with practical concerns: the legal complexities and costs associated with moving human remains internationally from one museum collection to another.

"The National Museum of Iceland welcomes a conversation on the repatriation of the skeletal remains from Haffjarðarey,” says Harpa Þórsdóttir, director-general of Iceland’s National Museum, in a statement to National Geographic. “Ultimately, we want what is ethically best for the collection, while also considering the importance of their long-term preservation."

Iceland has a long history of successful repatriation. The sagas, hugely important cultural manuscripts on Icelandic medieval life and mythology, formed the foundation of Iceland’s case for independence, Pálsson notes. Denmark returned many of the saga manuscripts in a series of high-profile repatriations following Iceland’s independence. Some scholars are still pushing to get the rest back, to fill the newly opened Edda cultural center.

As repatriation gains steam in Iceland and globally, perhaps one day soon the Hastings-Stefánsson collection will return to Iceland, and the heads of Haffjarðarey will rejoin their bodies after more than a century apart.