Why the life of Jack London was as wild as his books

He was the penniless itinerant who, after stints as a sailor, a pirate and a gold digger, became a literary star – before the excesses of adventure cut his life short.

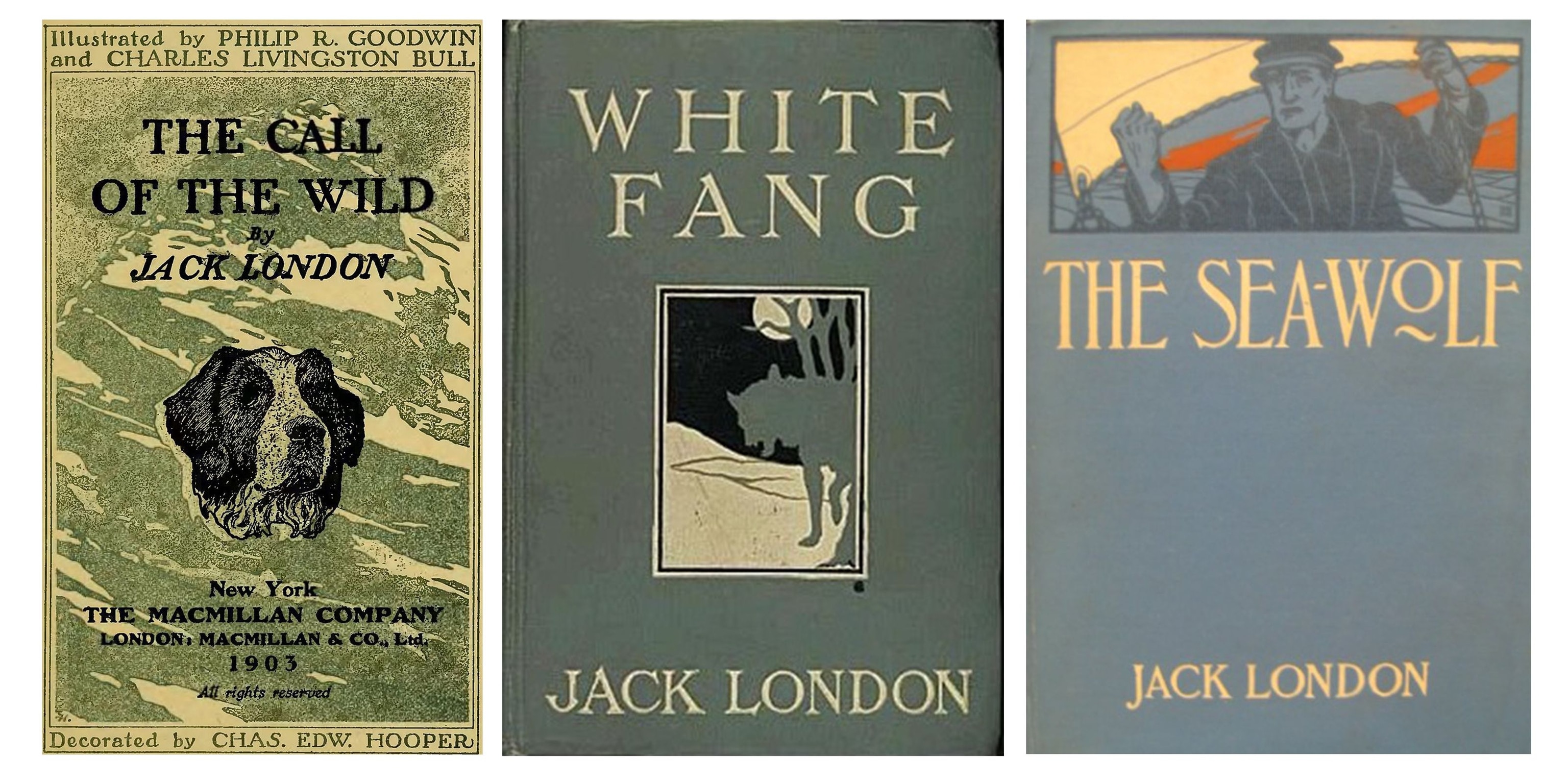

The Call of the Wild is a novel about friendship, loyalty and rediscovering the lure of primal nature and wilderness. It features the character of John Thornton—a Canadian gold hunter who befriends a dog named Buck against the elemental backdrop of the Klondike gold rush.

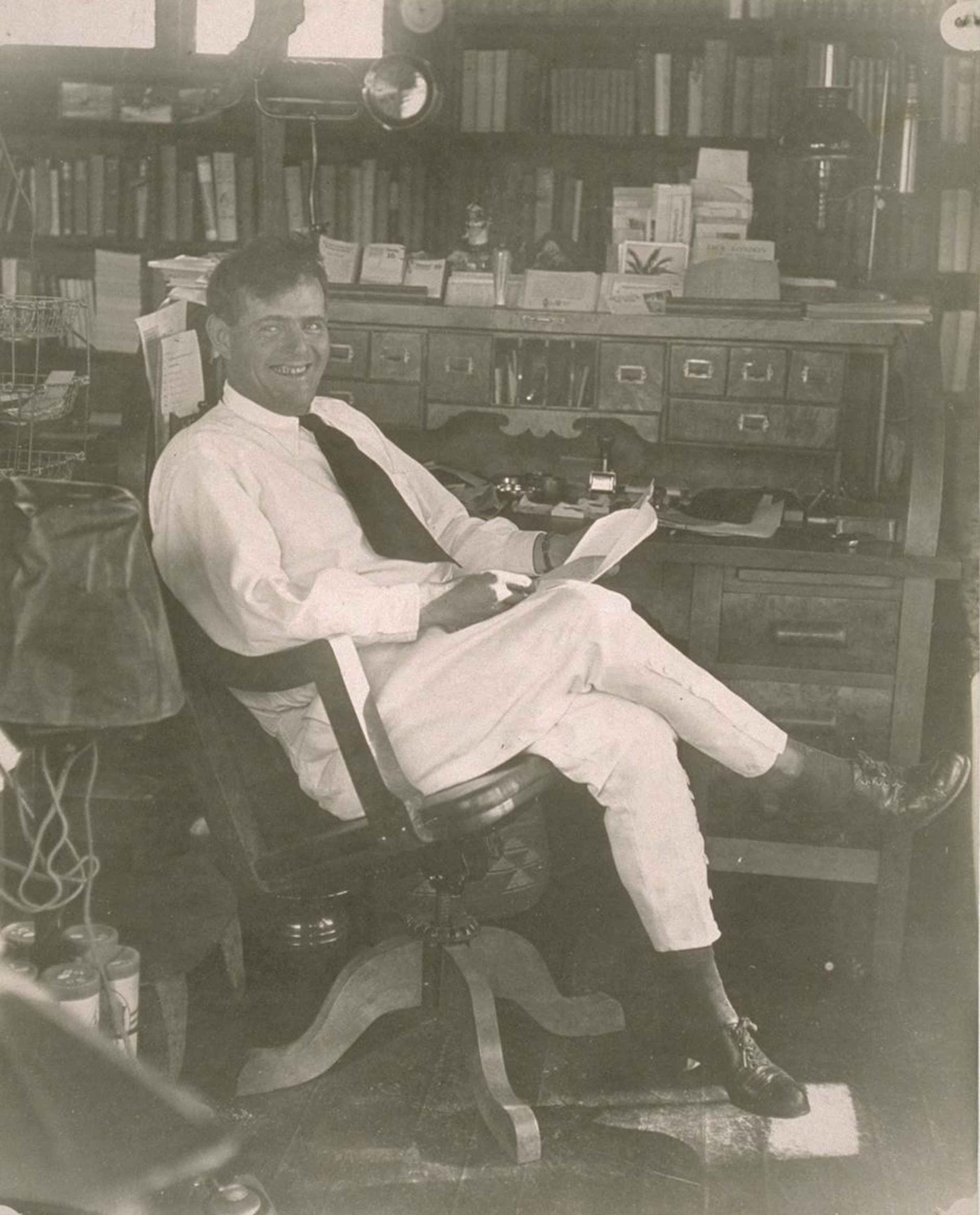

It was written in 1903 by Jack London—and is today considered amongst the greatest American novels of all time. The book’s success, along with its follow-up White Fang (1906) and a prolific canon spanning 50 books, made London one of America’s highest-paid and most widely-translated writers. Meanwhile, his charismatic personality and adventurous lifestyle made him one of the first literary celebrities.

But London’s own life journey from poverty to literati was unlikely, troubled, and short —ending in much-misreported circumstances at the age of 40.

Baptism of adventure

The man who would become Jack London was born in San Francisco as John Griffith Chaney, in 1876—the son of a music teacher-cum-spiritualist mother Flora Wellman, and a traveling astrologer father named William Chaney. The latter is alleged, as Chaney denied parentage and left before young John was born. Passed into the care of an African-American named Virginia Prentiss as his mother struggled with her mental and physical health, Wellman and her young son were later reunited when she married civil war veteran John London—and moved the family to Oakland, California.

Taking his stepfather’s last name (and modifying his first) London left school at 14 and began a series of grueling subsistence occupations in the San Francisco bay area. These included a stint as an oyster pirate—a crime punishable with a prison sentence —and another, ironically, with the government fish patrol.

This forced London to become a tenacious sailor, and in 1893 he signed on as an able-bodied seaman on the Sophie Sutherland, a seal-hunting ship bound for Japan via the wild northern waters of the Bering Sea. He was 17 years old.

Returning to America into the dissent of labor wars, and the depression that became known as the Panic of 1893, London joined the protest march of Coxey’s Army. This consisted of unemployed workers moving in groups across the country to Washington, D.C. to demand an expansion in infrastructure—and therefore jobs—for the masses. After being jailed for 30 days as a vagrant, London returned to California and briefly enrolled at the University of California, Berkeley, until he ran out of money. Then exciting news came in from the north.

The lure of the gold

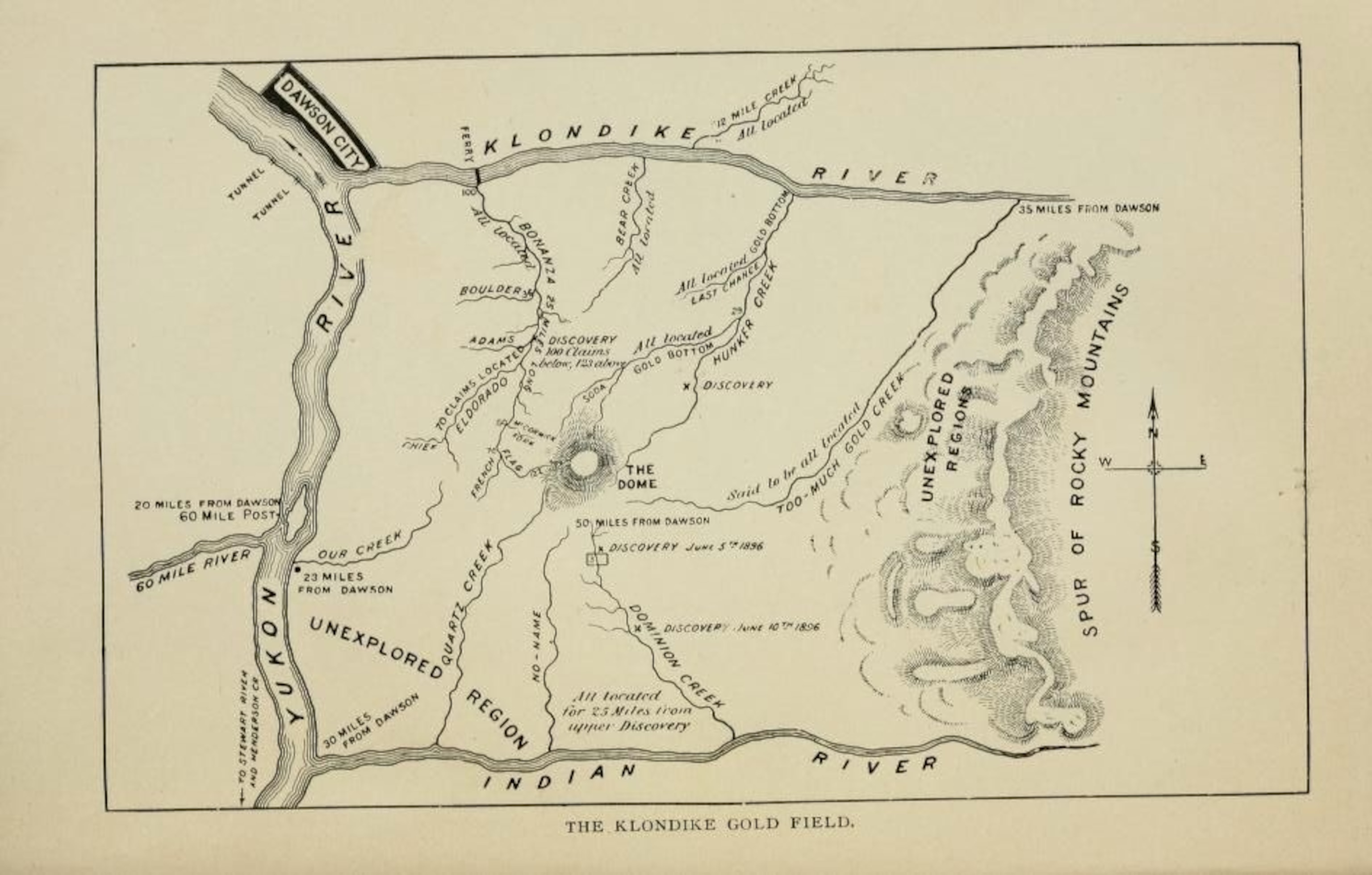

In August 1896 a group of miners struck gold in Rabbit Creek, near Dawson City in the Klondike region of Canada’s Yukon Territory. Over the next three years, an estimated 100,000 prospectors set off for the Yukon by boat from cities on America’s West, such as Seattle and San Francisco. Only 30,000 are said to have made it to the goldfields across the brutal backcountry—amongst them Jack London.

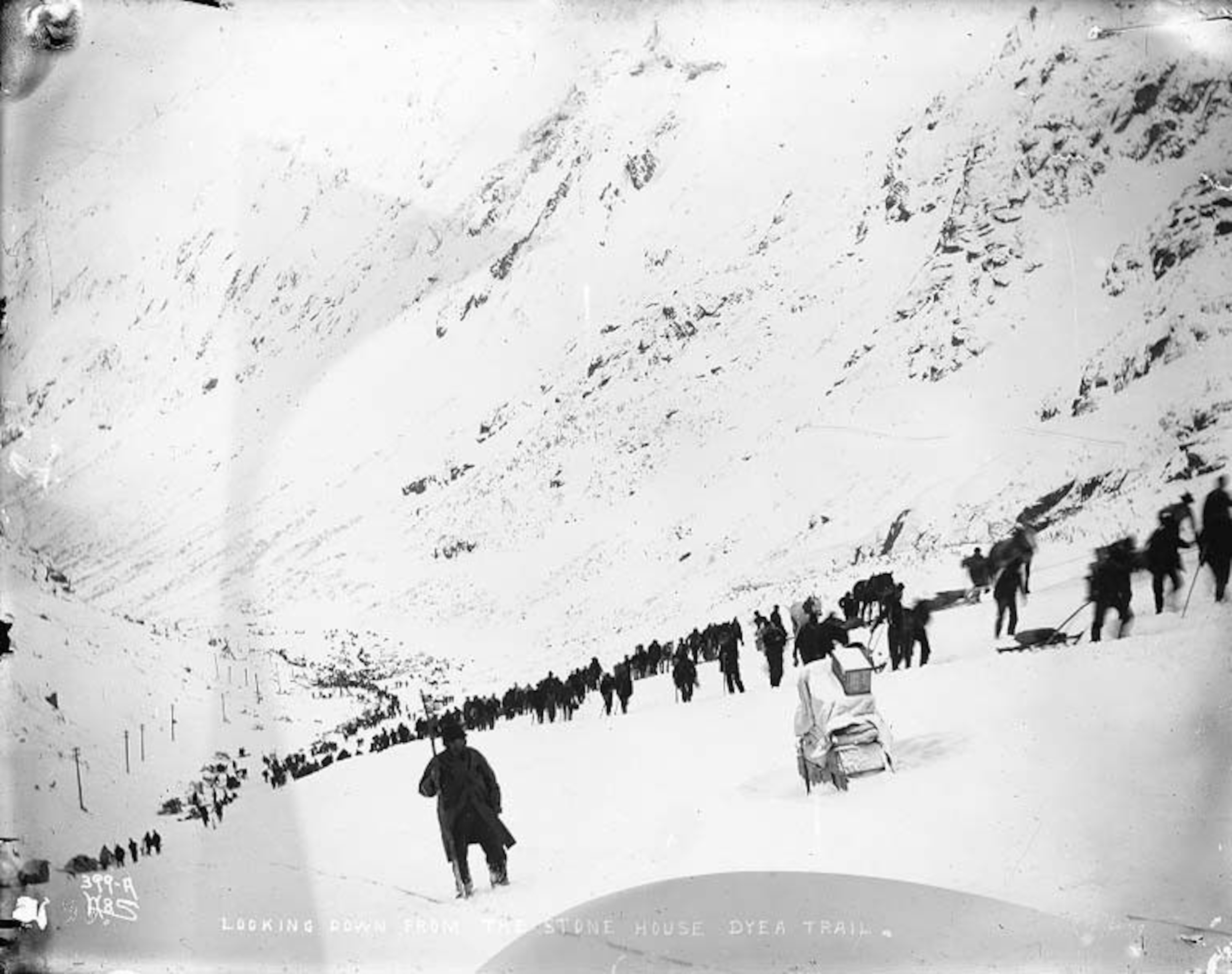

Conditions were desperate. Stories of malnutrition, drownings in quagmires under heavy loads, extreme cold and hunger-triggered insanity by Klondikers desperate to strike it rich feature in many accounts of the period. Many took up employment with so-called ‘Klondike Kings,’ who monopolised areas rich in finds, and paid prospectors a wage to line their own pockets with gold.

After landing in Alaska, Jack London and his band of well-supplied prospectors navigated a series of lakes and river rapids, through the Alaska Range to the Chilkoot Pass—where Alaska ended, and the Canadian Yukon began. This dreaded, snow-thick steep sometimes required up to 40 ascents and descents to move food and equipment to its top where a slum of exhausted Klondikers began to grow.

Staking out a 500ft area at the side of the Stewart River, Jack London returned to Dawson City to file his claim. His downtime in the smoky, character-rich saloons of the 'gold rush city' were a warm contrast to the hardships of digging for gold in a wretched, freezing riverbank—and it’s here the seeds were cast for many of the characters of the books to come. These included a St Bernard-collie mongrel named ‘Jack’ belonging to two brothers he had met, who’d allowed London to camp beside their cabin. The dog’s owner, Marshall Bond, would write of his tenant that he “had an appreciative and instant eye for fine traits, and honored them in a dog as he would in a man.”

Eventually a combination of malnutrition and lean pickings led London to return to California after 11 months in the Yukon. He later wrote ‘I brought nothing back from the Klondike but my scurvy’, though this wasn’t quite true. His intense experiences in Canada and his decision to escape the ‘work trap’ by trying to earn a living as a writer combined—yielding several short stories dealing with existential and elemental themes on the stage of the uncompromising far north. “It was in the Klondike that I found myself.” he later wrote. “There nobody talks. Everybody thinks. There you get your perspective. I got mine.”

Characters London met in the north became characters in his stories—and in 1903, the turn came for Marshall Bond’s dog. ‘Jack’ became ‘Buck,’ the stolen Californian mutt that travels north to work as a sled dog, and is the lead character in what would become London’s first great literary triumph. Buoyed by good reviews and sell-out copy sales, The Call of the Wild was published in 1903 to instant success.

‘Ahead of his time’

Jack London was married to teacher Bess Maddern in 1900, and the couple had two daughters. In 1904, London embarked on a sortie as a war correspondent, filing reports from the Japan-Russian conflict for the San Francisco Examiner. Traveling to Japan on the SS Siberia, London found himself in a cohort of hard-drinking journalists known as ‘the Vultures,’ which included correspondents from the New York Herald and The Times.

His dispatches were controversial, and were seen by some to fuel fear and bias against rising Asian powers against the west, and attest a racial bias in London himself—even white-supremacist sympathies. A committed socialist from his days in Coxey’s Army, London’s stances on race have been interpreted inconsistently, with leading biographer Earle Labor describing London’s views as ‘a bundle of contradictions.’

However, later analysis of London’s dispatches from the Japanese-Russian war by Daniel A. Métraux in the Asia Pacific Journal argued that London was in fact the opposite; a perceptive liberal who empathised with the underdog and prophesized later conflict. “A close examination of London’s writing shows… he was ahead of his time intellectually and morally,“ wrote Métraux, describing his dispatches from the war as “balanced and objective reporting, evincing concern for the welfare of both the average Japanese soldier and Russian soldier and the Korean peasant, and respect for the ordinary Chinese whom he met.“ London would later write the futuristic story The Unparalleled Invasion (1910), which depicted the annihilation of China by a malicious West. In her analysis of London’s short fiction, Jeanne Campbell Reesman described the story—set in 1975—as ‘a strident warning against race hatred and its paranoia, and an alarm sounded against an international policy that would permit and encourage germ warfare.’

London’s work both traversed and transcended his own experiences—with some of his most acclaimed work relatively obscure. “London wrote dozens of top-notch short stories. ‘A Piece of Steak,’ ‘Koolau the Leper', and ‘South of the Slot’ (all 1909) are three excellent examples,” says Kenneth Brandt, Professor of English at the Savannah College of Art and Design, and editor of The Call, the magazine of the Jack London Society. “He once claimed that The People of the Abyss (1903), an exposé of the impoverished conditions in London’s East End, was the favourite of his works. Posing as a homeless man, London went undercover to [research] the book first-hand.”

The call of the ocean

With a steady income and worldwide acclaim, London could afford to indulge two of his steering interests: the land, and the sea. Following the collapse of his first marriage in 1904, London had married Charmian Kittredge, and in 1906 commissioned a custom-designed 55ft ketch called the Snark—named after Lewis Carroll’s nautically flavoured nonsense poem. The construction of this boat illuminates London’s adventurous and ultimately unwise attitude towards investment: of the ballooning cost of the Snark—$30,000 versus an original budget of $7,000—in a San Francisco still reeling from the 1906 earthquake, London wrote simply “I signed the cheques and I raised the money.”

Despite the boat’s modest size, he intended to sail the Snark around the world on a multi-year expedition. An article in July 1907’s Popular Mechanics magazine reported that London was about to spend ‘seven years looking for trouble’ on the vessel, before adding that it was equipped with every modern convenience and ‘a small arsenal of shotguns, rifles, revolvers and one rapid-fire gun.’ He later penned an account of the voyage, The Cruise of the Snark (1911) – and his South Sea Tales (1911), a collection of short stories written about the voyage, is considered one of London’s finest works.

The tone of the Popular Mechanics story suggests the public persona of London as an extravagant, adventuring hell-raiser in the mould Ernest Hemingway would later fill. London was certainly adventurous, and not just in his investments: the first half of the Snark's voyage, from San Francisco to Hawaii, was a melee of contaminated fuel tanks, a leaking hull, storms, DIY dentistry, bad navigation and voyages into the territory of alleged cannibals. The adventure ended prematurely in Australia when London developed, as just one of a fiesta of ailments, yaws—a crippling skin condition that prevented him from his contractual writing duties aboard. Exhibiting fever, a sloughing of his skin, rapid thickening of his nails and all-over psoriasis, it was feared he had leprosy; five weeks in an Australian hospital were followed by five months convalescing in a hotel. Medical staff were stumped, and only a return to California cured him. London himself described it as a ‘happy, happy, voyage.’

‘A variety of identities’

London’s optimistic attitude towards the Snark's nautical escapades perhaps says a lot about his character as one who thrived on adventure and all its collective experiences, rather than one who went looking for trouble. “He wanted it all, craved a bunch of everything, and seemed able to inhabit a variety of identities at once: professional writer, gold rusher, socialist, sailor, bohemian, swashbuckler, political agitator, farmer, surfer, journalist. The list goes on,” says Kenneth Brandt. “London had an extremely fertile imagination and was remarkably energetic and efficient.”

Fever, a sloughing of his skin, rapid thickening of his nails and all-over psoriasis, it was feared he had leprosy. London himself described it as a ‘happy, happy voyage.’

His love of what he described as a ‘return to the soil’ led him to purchase, by piecemeal over the course of his career, what would become a 1400-acre swathe of land in Glen Ellen, California. Here he ran a farm, managed land and built ‘Wolf House,’ a grand 26-room property featuring a 760-ft library and built of local redwood and stone that was to be the home for London and his wife.

But London’s dream of a romantic and sequestered life in the house he hoped would ‘stand for a thousand years’ life was dealt a cruel hand on the night of August 22, 1913, when workers on the ranch noticed a glow in the sky. Wolf House was ablaze— and everything except the house’s stone walls was destroyed. The couple were due to move in imminently; arriving at the blaze by horseback, there was nothing they could do but watch.

The night had been hot, but calm—and the uncanny timing and no obvious cause led Charmian London to write that it was an ‘indisputable fact that it was set afire by some enemy.’ Many rumours circulated in the aftermath, and many suspects suggested, from disgruntled ranch hands, to resentful neighbors, to Charmian herself, shunned and aggrieved by her husband’s dedication to the build.

No cause for the fire was discovered until 1995, when an investigation by forensics analyst Bob Anderson pointed to self-heating and spontaneous combustion of a pile of cotton rags soaked in linseed oil—probably left by careless cabinet-makers—that likely led to the house’s loss.

The personal investment in the property, both financial and emotional, was considerable. Charmian wrote that the loss of the house ‘killed something in Jack.’

Cost of excess

London’s extravagance on his agricultural projects, and the construction—and destruction—of Wolf House, had put him under considerable financial pressure. This wasn't helped by the fact the insurance policies he had taken out fell woefully short of the property’s value.

His output was prolific; 49 books in 17 years, along with the many articles and short stories that comprised his journalism career, and one book completed posthumously. But despite his success, the scale of his lifestyle meant he remained permanently strapped for cash even before the loss of his property. It was reported in 1910 that London had sold his beloved Snark in Sydney to an Englishman for a mere $4,500—a fraction of its cost. And London's rigorous, self-imposed writing target of a minimum of 1,000 words a day was thought by many to be due to need, rather than desire, though it's little argued that London had any trouble hitting it.

In addition, by the time of the Wolf House fire, the author was already in fragile health. A lifelong smoker, the Klondike had dealt an early hammer-blow to his constitution. Like many gold rush prospectors, he suffered malnutrition and scurvy, losing his front teeth and enduring severe lower body pain. He recovered, but his further ailments in the South Pacific, along with a drinking habit nurtured aboard ships on cold seas and in the saloons of Dawson City all took their toll. It’s thought that the toxic mercury chloride he used to treat the yaws skin lesions, contracted while sailing on the Snark, may have caused the kidney disease that shortened his life. London died in November 1916 on his California ranch, aged 40.

Given the complicating factors of illness and fame, it wasn’t a straightforward death. Conflicting medical reports, vials of morphine with notes calculating an overdose, even whispers of deliberate poisoning distracted from the death certificate’s prosaic ruling of ‘uraemia following renal colic.’

As a result, rumours of suicide dogged Jack London’s legacy, and in some quarters dog it still. “'Suicidal drug overdose’ grabs more readers than ‘death from kidney disease,’” says Kenneth Brandt. “The suicide story packs even more sensation into an already hyper-romantic life story. Drama always wants more drama.“

Legacy of adventure

Jack London’s name today can be found in his books, landmarks, multiple organisations dedicated to his memory, and a State Historic Park on the site of his former ranch—where the ruins of Wolf House still stand. In the recent movie, Harrison Ford is the eighth actor to play John Thornton onscreen.

And while London’s work is sometimes described as a case of quantity over quality, his popularity was incontrovertible. At its best, many believe London’s work ranked amongst the literary greats—though it’s only in relatively recent years this has gathered appreciation. “The mid and later-20th century literary establishment favored the formal complexities of writers such as William Faulkner and T. S. Eliot over London’s direct, accessible style,” explains Kenneth Brandt. “More recently, though, scholarship on London has flourished as critics have become more interested in race, class, gender, environmentalism, and animal studies—subjects that London wrote about repeatedly.“

Critics aside, what London inarguably distilled was high adventure, in a way that continues to excite. As described by the late Pulitzer-winning journalist Tony Horwitz in the introduction to the 2002 edition of South Sea Tales, “when London’s stories click, we are utterly there—at the edge of the world and the limit of human endurance.”

This story was adapted from the National Geographic U.K. website.