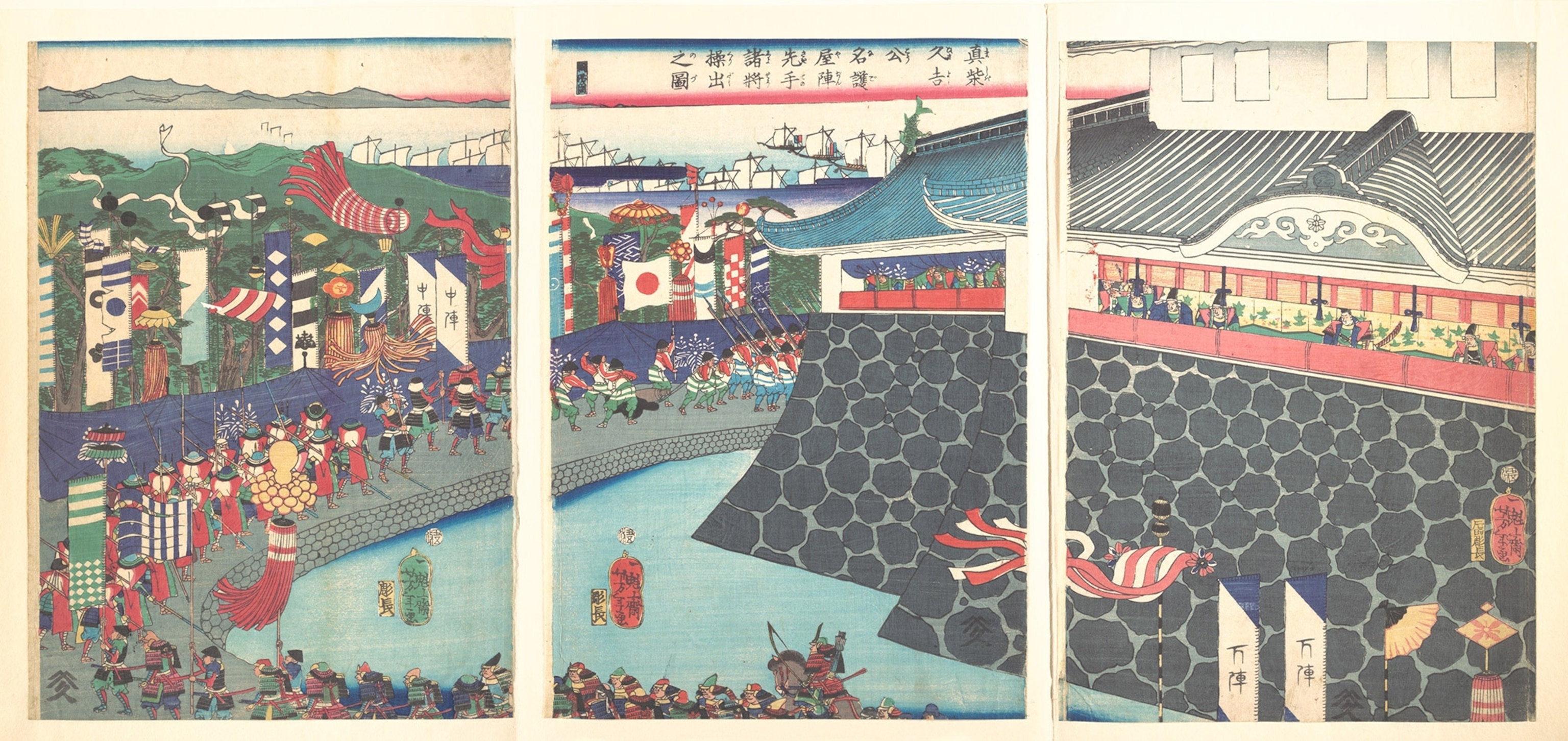

The three samurai who unified Medieval Japan

These shrewd leaders led their armies to multiple victories on the battlefield that put the island nation closer to unification after decades of political turmoil.

Starting in the late 12th century, Japan evolved into a feudal realm. While the emperor was the named head of state, military commanders known as shoguns were the de facto rulers. Serving their leader, local feudal lords, called daimyo, oversaw regional provinces. Each daimyo, who typically came from the samurai class, relied heavily on the elite, highly trained samurais, to defend his estates and expand his lands in exchange for their own property.

Eventually, rival daimyos brutally fought for control and dominance over Japan. Things reached a climax during the Sengoku period, also called the Warring States Period (1467–1573), which was a time of intense warfare and political turmoil. Over time, the daimyo became fewer in number, with field armies numbering tens of thousands of samurai warriors.

But it wasn’t until three indomitable daimyo, with the support of their samurai, ascended in succession above the fighting fray did Japan have a shot at unification. Here are the fascinating stories of Nobunaga, Hideyoshi, and Ieyasu.

Number one: Nobunaga

Oda Nobunaga (1534–1582) was a relatively obscure warlord who rose to prominence in the 1560s. Under cover of a thunderstorm, he staged a daring attack against rival daimyo Imagawa Yoshimoto, whose armies had paused in a narrow gorge known as Okehazama. His soldiers descended upon his enemy’s much larger forces and defeated them within 15 minutes. His reputation as a formidable leader was clinched.

Through a series of strategic family marriages and equally strategic battles, Nobunaga went on to consolidate control of many of his opponents’ territories. His armies, formerly split into diverse clan units, became a more centralized force with soldiers organized by function. Among them were warriors using a weapon new to Japan: the firearm.

Gun power

The first guns, long-barreled firearms called harquebuses, had arrived with shipwrecked Portuguese sailors in 1543. Japan’s skilled metalworkers rapidly deciphered them and began to produce arms for the warring daimyo. Quick to seize on this promising new invention, Nobunaga was the first to organize units equipped with muskets. In the 1575 Battle of Nagashino, his gunmen demonstrated their defensive value by destroying the enemy’s advancing cavalry from behind a palisade.

By 1582, Nobunaga had conquered central Japan and was attempting to extend his control over western Japan. In June that year, he sent troops to aid an ally, Toyotomi Hideyoshi. One of Nobunaga’s vassals, Akechi Mitsuhide, rebelled and attacked him within a temple in Kyoto. As the temple burned around him, the wounded Nobunaga committed seppuku (ritual self-disembowelment).

By the time of his death, Nobunaga had succeeded in bringing nearly half of Japan under his control.

Number two: Hideyoshi

Nobunaga’s assassin lasted approximately two weeks in power before he, in turn, was destroyed by Nobunaga’s ally Hideyoshi (1537–1598). This talented commander, the son of a woodcutter, added to Nobunaga’s territories in a series of bold battles through the 1580s. He was as shrewd in peace as in war. In 1588’s Great Sword Hunt, in which he aimed to disarm the peasantry, he confiscated swords from all non-samurai, claiming he needed to melt down the weapons to build a statue of the Buddha. This measure helped consolidate the power of the ruling class and reduce the possibility of uprisings. Powerful retainers, in addition, were “rewarded” for their service with lands far from their traditional centers of influence, further bringing most of the country under his control.

Destroying the castles of his more minor rivals, he went on to build several impressive castles throughout Japan, including Osaka Castle. This magnificent fortress served as his power base and a symbol of his authority. Hideyoshi’s castle-building projects contributed to the development of advanced architecture and engineering techniques.

Power vacuum

After two failed invasions of Korea in the 1590s (the Imjin War), Hideyoshi died in 1598, leaving behind a young son and a power vacuum. Rival forces faced off to seize control. The armies to the west, commanded by Ishida Mitsunari, gathered together to take on the forces to the east, commanded by Tokugawa Ieyasu, previously one of Hideyoshi’s most powerful retainers.

The two armies met at the village of Sekigahara, northeast of Kyoto. On a foggy, rainy October morning in 1600, they engaged in a huge field battle, with Ieyasu’s 89,000 men against Mitsunari’s 82,000. Loyalty, or its absence, eventually decided the conflict. Two of Mitsunari’s discontented daimyo had secretly told Ieyasu they would not obey their leader’s orders. When these troops failed to move on his commands, Mitsunari was forced to retreat, and Ieyasu claimed victory.

Number three: Tokugawa Ieyasu

With this triumph, Tokugawa Ieyasu (1543–1616) took control of Japan, and the powerless imperial court named him shogun (military dictator) in 1603—thereby officially ending the Warring States Period. He embarked on construction projects, including building a vast castle at Edo (later Tokyo).

In 1605, Ieyasu “retired,” handing off the reins of shogun to his son, Hidetada—in effect, serving notice that since the shogun in theory was the servant of the figurehead Japanese emperor, it was the House of Tokugawa that was Japan’s real dynasty.

One final push

Yet one threat still remained. Hideyoshi’s heir, Toyotomi Hideyori, now a young man, was ensconced in Osaka Castle, surrounded by retainers and masterless samurai. Looking for a pretext to attack him, Ieyasu claimed Hideyori had insulted his family in an inscription on a temple bell.

In the winter of 1614–15, the aging Ieyasu besieged the powerful castle. As in Sekigahara, he eventually overcame his enemies through trickery, in addition to force. During a truce, Ieyasu’s men filled in Osaka Castle’s protective moats and, lacking this defense, the castle fell to the enemy. The castle, Japan’s mightiest fortress, could fight off intense military force, but it couldn’t withstand the determined ruses of an old samurai. Hideyori and his family committed ritual suicide.

Ieyasu died the following year, but his legacy lived on until 1867 in the Tokugawa (or Edo) period of Japanese history. Ieyasu’s heirs established firm control over the formerly contentious warlords, and the country knew stability and economic growth.

A warrior's wardrobe

But just as important as their dress was a code of conduct known as bushido, the “way of the warrior.” This code required not only prowess with their weapons, but also stoicism, fearlessness, honor, and supreme loyalty to their commander. They were expected to be skilled at martial arts, poetry, calligraphy, and other cultural pursuits. The greatest samurais possessed both physical and intellectual prowess.

To learn more, check out Atlas of War. Available wherever books and magazines are sold.