Who Was Saigo Takamori, the Last Samurai?

The stuff of legends and Hollywood movies, Japan's samurai are known for tradition and swordsmanship. But their last defender came to symbolize a conflict over modernization.

A leader of Japan’s 19th-century drive to modernize, and at the same time a defender of its ancient samurai values, Saigo Takamori's dramatic last stand embodied his nation’s identity crisis.

Samurai were a caste of warriors prevalent in Japanese society from the 12th to the 19th century. Respected for their military prowess, swordsmanship, and discipline, they valued honor, courage, and loyalty above all. Political change brought about the end of their era, but the samurai did not go down without a fight. They were led by Saigo Takamori, who both embraced and fought the forces of modernism and became one of Japan’s great national heroes in the process.

Foreign Influences

In 1852 Commodore Matthew Perry of the U.S. Navy embarked on a mission to open Japan to the United States and the rest of the world. In an effort to keep out foreign influences and protect its culture, Japan had been under self-imposed isolation. Faced with Perry’s warships, the Japanese saw they had no choice and opened their ports to the U.S. ships. Japan eventually signed the Treaty of Kanagawa, the first between the two nations.

The controversial treaty revealed weaknesses in Japan’s government, a military dictatorship known as the shogunate that had effectively ruled the nation as a feudal state since the early 17th century. Political revolution broke out in 1868, the shogunate fell from power, and Emperor Meiji took control. The capital moved from Kyoto to the old shogunal power center of Edo—renamed Tokyo (“the eastern capital”).

The Meiji Restoration, as it came to be known, was about much more than a change in the system of government. Its leaders believed that Japan could only resist outsiders if it could match them. Modernization would be the key to protect their nation. Two centuries of isolation had rendered the state vulnerable to the outside world. “Enrich the country, strengthen the army,” was the slogan of the Meiji restorationists. The new regime began dismantling the old feudal system and building a modern fighting force.

Not all Japanese, however, welcomed these dramatic changes. The Meiji reforms deeply split the samurai. Some supported this modern vision for Japan, seeing how it would help preserve national autonomy; but to other samurai, the tide of modernity threatened their very way of life. Saigo Takamori, a samurai hero who helped lead the Meiji revolt, came to embody the deep conflict between old ways and new advances.

Birth of a Samurai

Born in 1828, Saigo hailed from Satsuma (modern-day Kagoshima), a han (fief) in southwestern Japan. His family was of modest means but deeply proud of their samurai lineage. He grew into an imposing figure, standing six feet tall and weighing about 200 pounds.

Saigo was not only a skilled warrior but also dedicated to the ideas of neo-Confucianism and Buddhism. He became widely admired for his incorruptibility and piety. For instance, when his daimyo (lord) suddenly died, Saigo decided to follow the ancient practice of junshi, whereby after a lord’s death, a servant commits suicide. He and a friend jumped into a lake, and the current carried their bodies back to shore. His friend had drowned, but Saigo was revived. Each year, Saigo would think back on the event; on one occasion he wrote a Chinese poem to commemorate it: “Hand-in-hand, we leapt into the depths of the water . . . destiny thwarted my hopes and brought me back alive . . . Now the years have passed and I stand before your tomb, shedding vain tears.”

The new daimyo of Satsuma was suspicious of this austere samurai’s popularity and exiled Saigo to remote islands on two occasions. Saigo used these periods as opportunities to improve his calligraphy and Chinese poetry, practice sumo wrestling, and to reflect on how corrupt and unjust Japan’s shogunate system had become.

He was known for outbursts of misanthropy—“that herd of wild beasts who call themselves human beings”—yet he could also be modest and self-effacing. His ideal was to be “a man who is utterly unconcerned with his life, fame, rank or money.”

Saigo returned to Satsuma to play a leading role in the political and military struggles of the mid-19th century. In 1868 Saigo’s troops occupied Edo, defeating the shogunate forces. As part of the package of reforms later introduced by Meiji, Japan’s ancient feudal system of military government, bakufu, was abolished. The consequences of this reform would come back to haunt Saigo.

Cost of Modernization

Immediately after the reformation, Saigo went back to Satsuma, but in 1871 he returned to Tokyo as the head of the newly formed Imperial Guard. He felt out of step with the new ways in the capital. Despising the craze for Western fashion, he continued to wear the traditional dress of his region, shod in sandals or clogs. It is said that on one occasion, as he was leaving his office in the middle of a storm, he removed his shoes and began to walk barefoot, which led a guard to believe he was an intruder.

Saigo was also increasingly uneasy about the new political measures the government was introducing. In 1871 the han system was abolished, and feudal lands passed into state ownership. The former regional governors were granted lifelong stipends and new government positions.

Abolishing the han system had grave implications for the samurai. It meant the end of their way of life. The stipends paid to them by their formal lords disappeared. The creation of the Japanese Imperial Army and the introduction of military conscription removed the need for their military service. For many, poverty loomed.

The samurai felt their status and prestige shrinking, as though they were becoming common citizens on a par with peasants. Banning their distinctive chonmage topknot, an 1871 edict decreed they had to wear their hair in Western fashion. By 1876 they were banned from carrying their swords in public. These measures were unacceptable to those who had fought to end the shoguate.

Saigo understood that Japan’s modernization was inevitable, even desirable, but he could not betray those who had fought under him. In desperation, he backed war with Korea in 1873, in hopes of reviving the samurai spirit through combat. After his proposal was rejected, Saigo resigned and returned to Satsuma where he set up a military academy.

Many young samurai were attracted to Saigo’s school. By 1877 he had an estimated 20,000 students. The popularity of his school fueled government suspicion that Saigo wasn’t running a simple school; he was training an army to launch a rebellion. When the government tried to confiscate weapons from Satsuma’s arsenal in 1877, the samurai took up arms and did indeed rebel.

Glory in Defeat

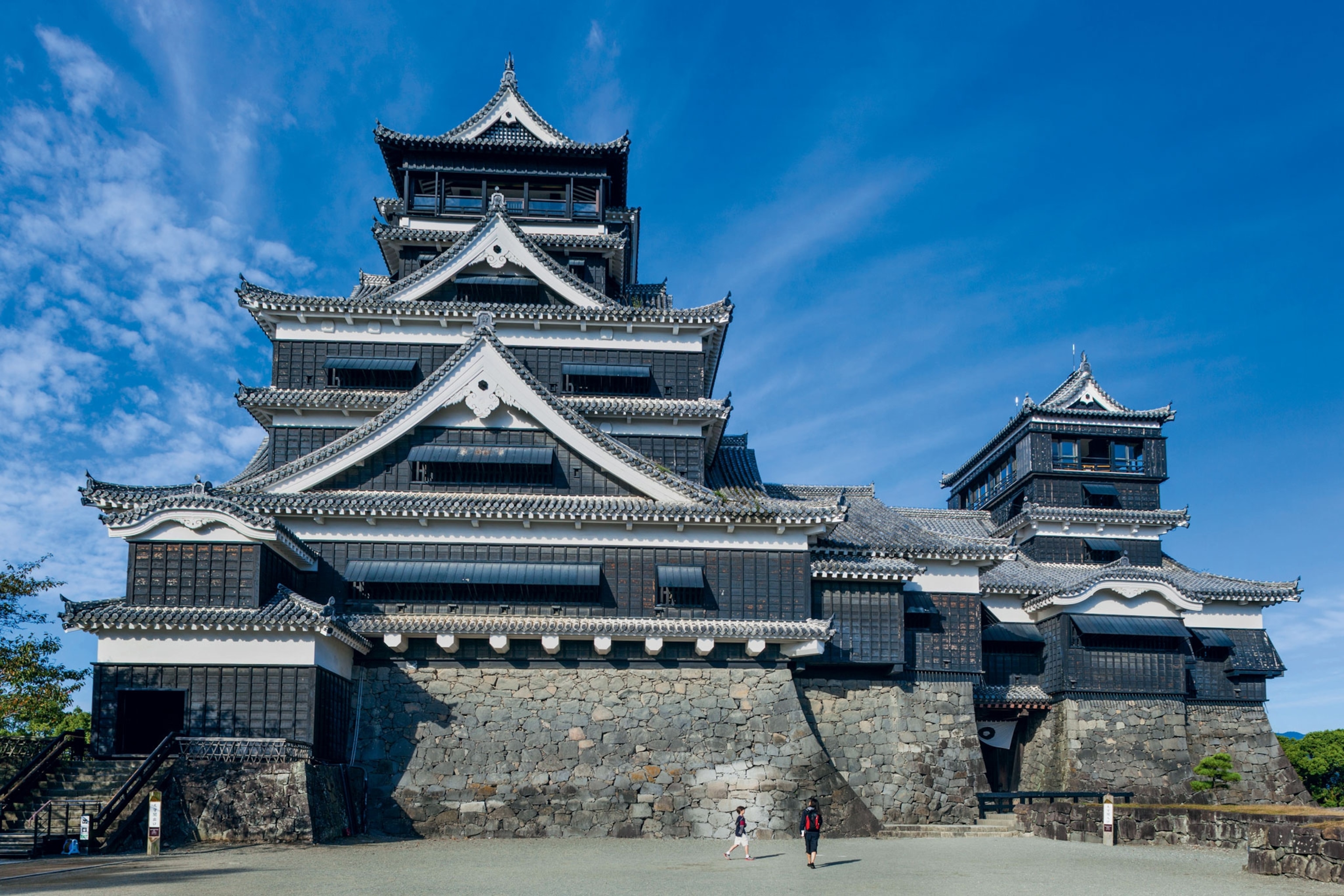

Saigo planned an attack on Tokyo, but his troops were rebuffed and withdrew to Satsuma, where they sought refuge on Mount Shiroyama. By September 22 they were surrounded. Saigo informed his troops that this would be their final battle and enjoined them to die bravely. He then decided to go and meet his destiny: Sources describe him as dressed in an austere yellow kimono, saber in hand. He charged down the hillside with a few last fighters. He was wounded by a bullet in his right thigh, felled by the modern army he had helped create.

According to tradition, he fell to the ground and told one of his fellow fighters: “Right here should do. Please do me the honor of decapitating me.” Although some dispute this theory, one account describes how he slowly sat up, looked in the direction of the Imperial Palace, solemnly gripped his dagger, and performed ritual disembowelment on himself—seppuku—before his head was cut off by a follower. The extent of the defeat suffered by the samurai cause was almost total. But his dignity and courage in facing the classic Japanese conflict between the quality of giri (duty) and ninjo (human instinct) has made him a national hero.