Toxic New Algae Species Discovered

Infections can cause lesions and potentially fatal complications, expert says.

A newly discovered species of algae can cause potentially deadly infections in people, a new study says.

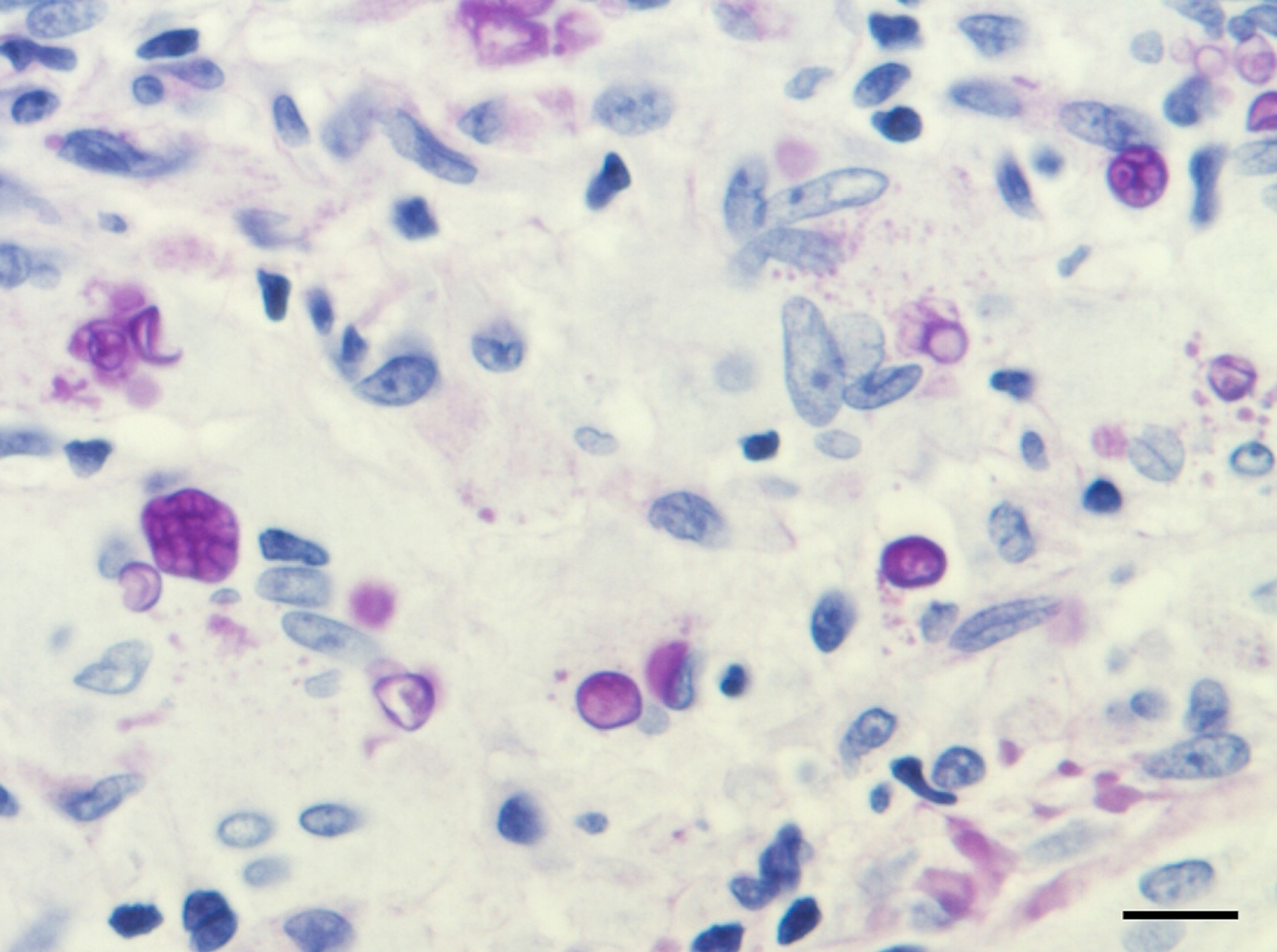

The new algae, Prototheca cutis, was discovered after scientists analyzed skin samples from a Japanese hospital patient, who had developed an ulcer as a result of the algae infection.

The researchers suspect P. cutis is found in soil and water everywhere on Earth, except Antarctica. Because the tiny organism is hardy enough to survive antiseptic treatments, such as chlorination, it thrives in sewage water and household waste—especially in rural areas.

The Japanese patient, who was successfully treated, is the only known P. cutis victim.

But study leader Koichi Makimura, a medical mycologist at Tokyo's Teiko University, suspects that the newfound species acts much like related types of harmful microalgae—single-celled organisms found in waters worldwide.

If so, P. cutis can enter an open wound—for example, through exposure to contaminated water—and create inflammations or ulcers in a person's arm, leg, or face. The lesions progress slowly, sometimes taking two weeks or more to develop, Makimura said by email.

Similar microalgae infections have also been reported in cattle, deer, dogs, and cats, he added.

(Related: "New, Deadly Cryptococcus Gattii Fungus Found in U.S.")

Rare Infection Lacks Effective Treatment

In severe cases, microalgae infections can progress into potentially fatal septicemia—microbes in the blood—or meningitis, an inflammation of the tissue around the brain and spinal cord.

Such reactions usually occur in weakened hospitalized patients, according to the study. (Explore the human body.)

Because microalgae infections are rare, treatment options are scarce, Makimura said. (Related: "Drug-Resistant Staph Infection Spreads to Gyms, Day Care.")

For now, antifungal medications are the only available drugs. Even though the algae is not a fungus, antifungals have been shown to cure 59 percent of patients with the most severe microalgae infections, he said.

Patients that can't be cured die from the most extreme infections, he said.

Still, most of the world's microalgae are "usually harmless," Makimura added, making the new species, P. cutis, an "important and interesting subject" of study.

Findings appear in the May issue of the International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology.