Finishing TouchesDrill manager Dennis Duling signs a particle-detecting sensor, part of the newly completed IceCube Neutrino Observatory, in Antarctica in December 2010.

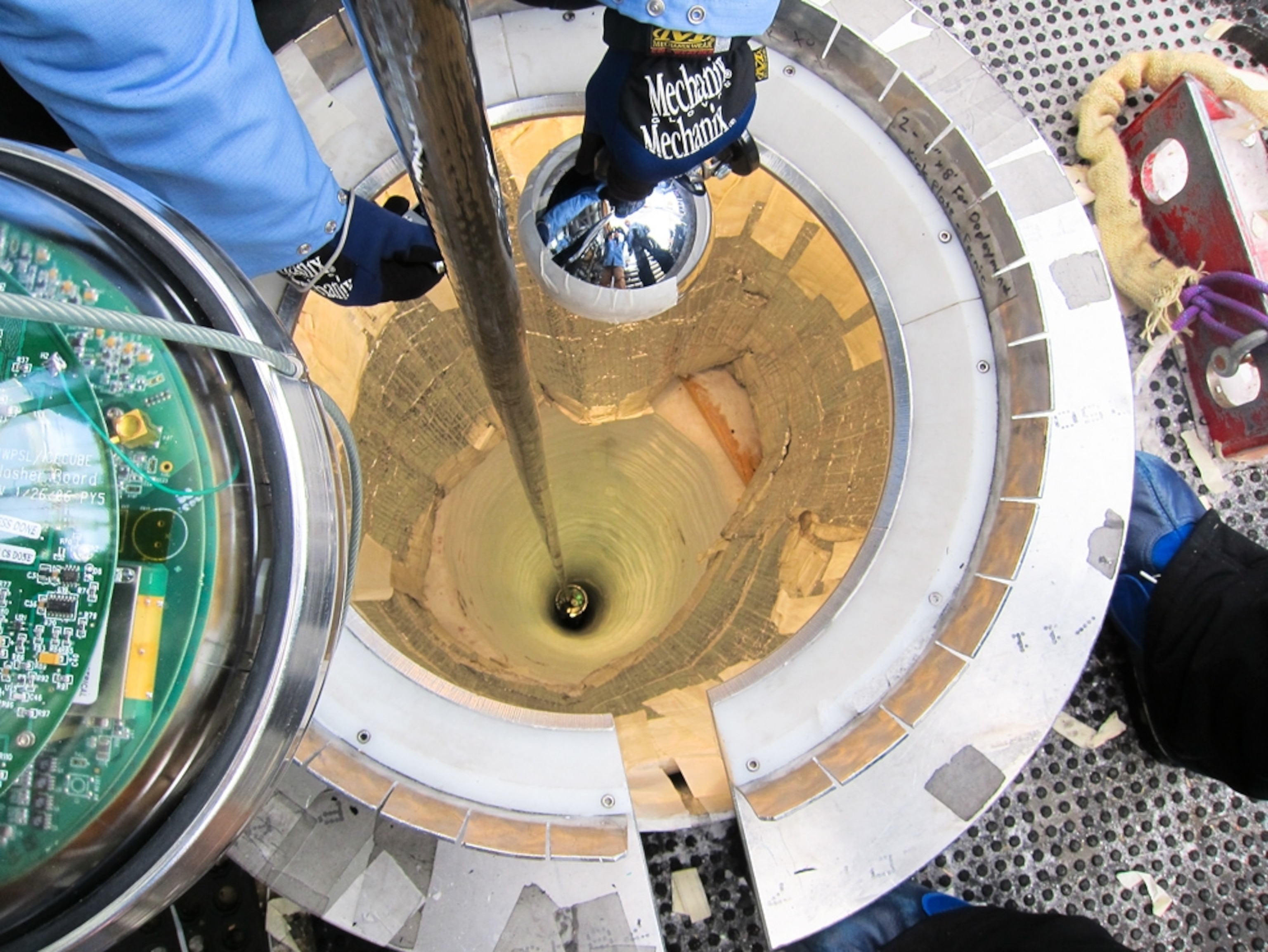

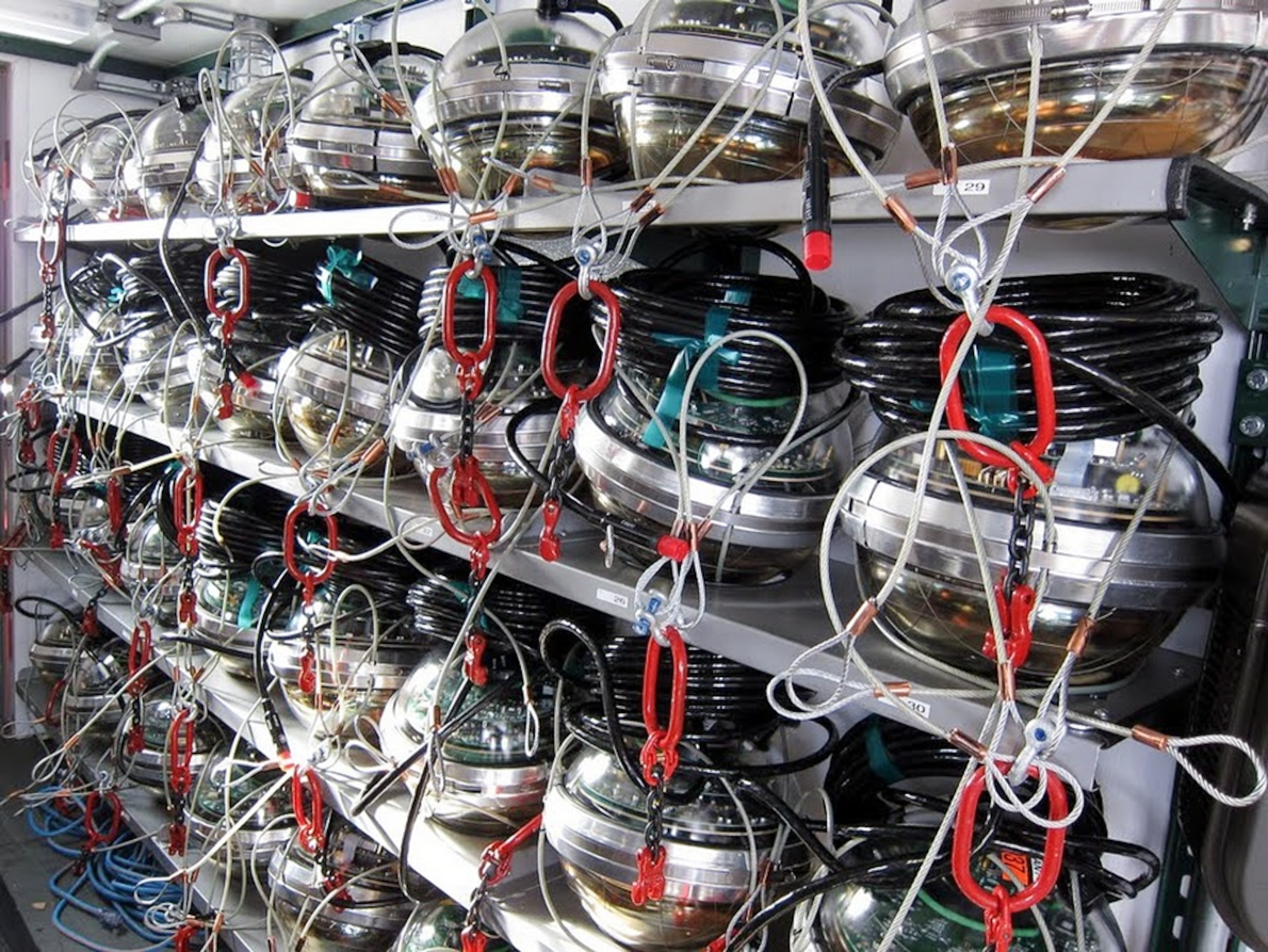

Situated at the geographic South Pole, the U.S. $279 million observatory—the largest of its kind—will search for neutrinos, mysterious subatomic particles that can travel through almost any type of matter. Neutrinos are born of some the universe's most violent events, such as star explosions, gamma ray bursts, and cataclysmic phenomena involving black holes and neutron stars, according to the IceCube website.Echoing some undersea neutrino observatories, IceCube is made of up 86 sensor-equipped cables that snake down ice holes as deep as 1.5 miles (2.5 kilometers). The cables are linked to a surface laboratory.(Related: "Particles Larger Than Galaxies Fill the Universe?")"The advantage of ice is that you can walk on your experiment," said Francis Halzen, a physicist at the University of Wisconsin at Madison and principal investigator for the IceCube project, which is funded by the U.S. National Science Foundation (NSF).Because the detectors will be frozen into the ice, scientists were able to place the surface-based data-acquisition electronics and computers right on top of the detector, Halzen said. In water, it's more difficult: Equipment must be more sophisticated and continuously fight a hostile environment of deep ocean water, for instance.For IceCube, "all we do is build a sensor, freeze them in, and [the sensors] live forever. It did turn out to be simple." —Christine Dell'Amore, with reporting by Catherine Ngai

Situated at the geographic South Pole, the U.S. $279 million observatory—the largest of its kind—will search for neutrinos, mysterious subatomic particles that can travel through almost any type of matter. Neutrinos are born of some the universe's most violent events, such as star explosions, gamma ray bursts, and cataclysmic phenomena involving black holes and neutron stars, according to the IceCube website.Echoing some undersea neutrino observatories, IceCube is made of up 86 sensor-equipped cables that snake down ice holes as deep as 1.5 miles (2.5 kilometers). The cables are linked to a surface laboratory.(Related: "Particles Larger Than Galaxies Fill the Universe?")"The advantage of ice is that you can walk on your experiment," said Francis Halzen, a physicist at the University of Wisconsin at Madison and principal investigator for the IceCube project, which is funded by the U.S. National Science Foundation (NSF).Because the detectors will be frozen into the ice, scientists were able to place the surface-based data-acquisition electronics and computers right on top of the detector, Halzen said. In water, it's more difficult: Equipment must be more sophisticated and continuously fight a hostile environment of deep ocean water, for instance.For IceCube, "all we do is build a sensor, freeze them in, and [the sensors] live forever. It did turn out to be simple." —Christine Dell'Amore, with reporting by Catherine Ngai

Photograph courtesy J. Haugen, NSF

Photos: Huge Observatory 1.5 Miles Deep in Antarctic Ice

Just completed deep under South Pole ice, the world's largest neutrino observatory is set to search for clues to cosmic mysteries.

Published January 7, 2011