1 of 18

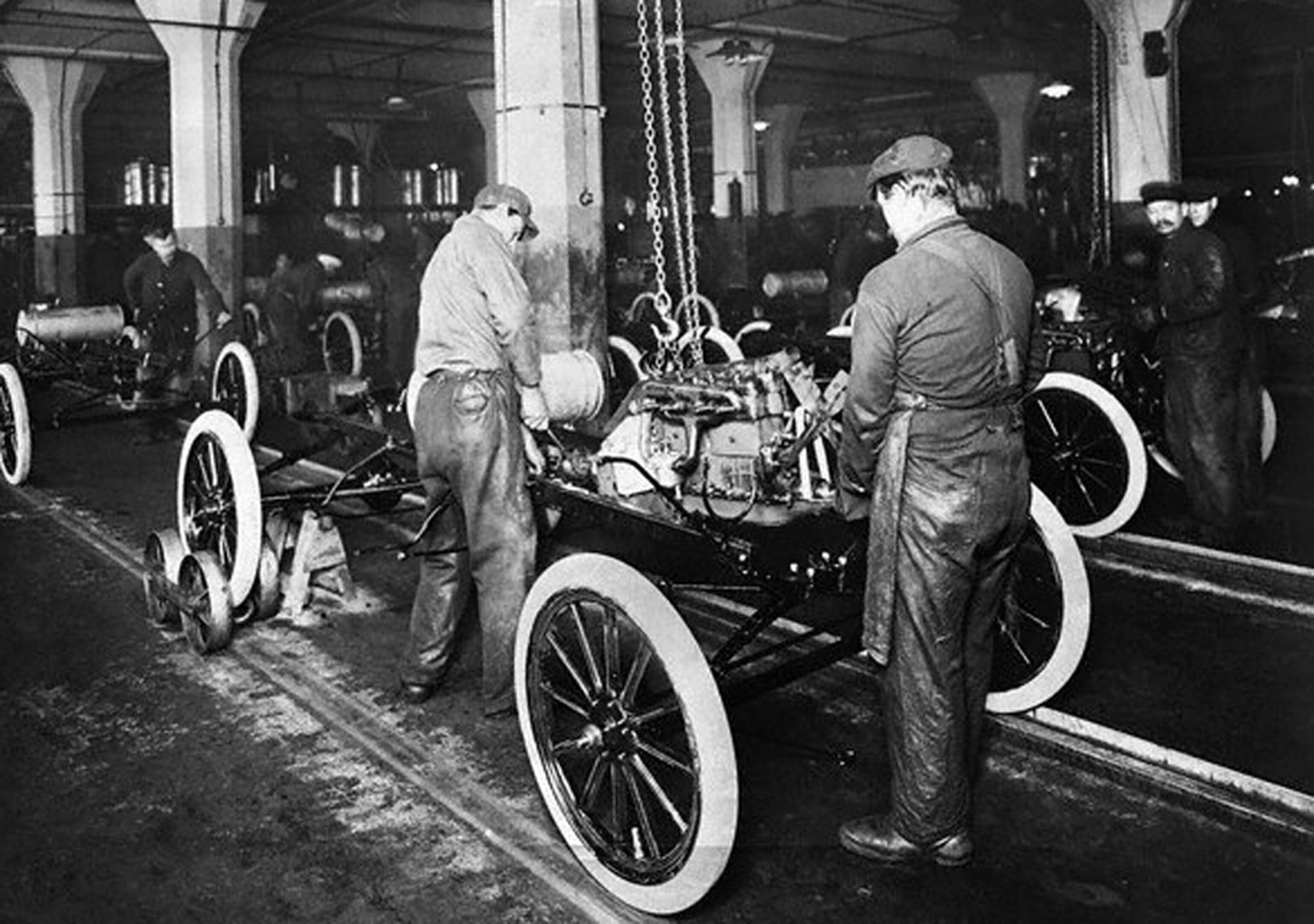

1803 Steam CarriageFew inventions have shaped more facets of modern life than the car. We spend hours behind the wheel each week, we live in cities and suburbs built around the automobile, and most painfully, we burn money as quickly as the fuel ignites in our engines.Global economic woes are holding oil prices in check as the Memorial Day weekend approaches in the car-centric United States, where the kickoff of summer driving season typically leads to a surge in prices at the pump. But whether gas prices rise or fall in coming weeks, the world happens to be focused as never before on improving the fuel efficiency of automobiles.(Related Quiz: What You Don't Know About Cars and Fuel)The European Union's 2020 goal that automakers achieve a fleet average equivalent to 64.8 miles per gallon (27.6 kilometers per liter), is the most ambitious, followed by Japan's, at 55.1 mpg (23.4 km/l) and China's, at 50.1 mpg (21.3 km/l), according to the International Council on Clean Transportation. This summer in the United States, the Obama administration is expected to finalize fuel economy and emission standards that call for phase-in to a fleet-wide average of 54.5 mpg (23.2 km/l) by 2025. That will mark quite a step up, as the most recent available worldwide data shows cars averaging 29 mpg (12.3 km/l), according to the Global Fuel Economy Initiative (GFEI).Nations are seeking to address not only the fuel cost to motorists, but the price the planet is paying for dependence on oil, and a sense that too much of this resource is being wasted in inefficient internal combustion.But today's global demand for more efficient cars follows two centuries of shifting attitudes toward fuel-guzzling vehicles. Fuel economy was hardly a priority in the early days of automotive innovation. "What was important was just getting the thing to run at all," Leslie Kendall, curator of the Petersen Automotive Museum in Los Angeles, said in an interview.The London Steam Carriage depicted here, built in 1803 by a Cornish mine engineer and former steam engine repairman named Richard Trevithick, used steam under high pressure to fire pistons. The high-pressure steam engine could be made more portable and powerful than the dominant low-pressure steam engines at the time, but the vehicle remained expensive to operate compared to horse-drawn carriages.According to Kendall, sharing the road with Trevithick's contraption—a "belching, snorting thing"—would have been terrifying for horses and people alike, though its top speed was only 10 miles per hour.(Related: Global Personal Energy Meter)—Josie Garthwaite This story is part of a special series that explores energy issues. For more, visit The Great Energy Challenge.

Illustration from SSPL/Getty Images

Pictures: Cars That Fired Our Love-Hate Relationship With Fuel

Today’s global demand for more efficient cars follows two centuries of shifting attitudes toward fuel-guzzling vehicles, from Model T to Rambler, from Hummer to Prius.

Published May 26, 2012