1 of 8

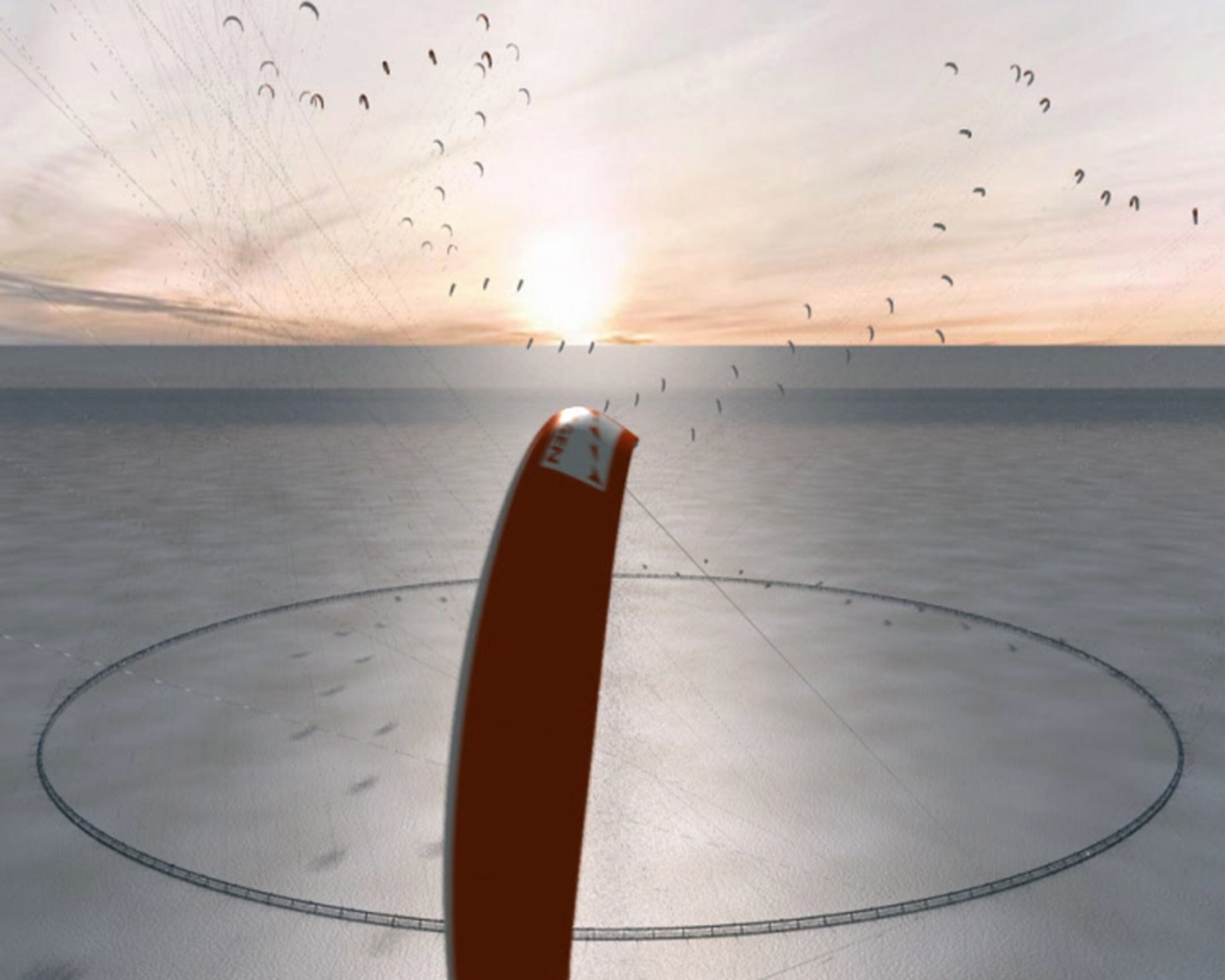

Photograph courtesy Makani Power

Pictures: Flying Wind Turbines Reach for High-Altitude Power

Airborne wind energy pioneers are trying to harness the potential of high-altitude breezes, which have enough force—a new study reckons—to power all of Earth's energy needs.

Published September 25, 2012