Is Deepwater Drilling Safer, 5 Years After Worst Oil Spill?

Deepwater drilling is increasing in the Gulf. Oil companies say it’s safer now, but critics say spills are inevitable.

One mile underwater in the Gulf of Mexico, trawling in darkness and near-freezing temperatures, car-size robots do more than shoot video of crabs, eels, and sea cucumbers: They also might help prevent oil spills. These subsea robots now carry tools that can seal a well within 45 seconds.

“We’re becoming a second fail-safe,” says Kevin Kerins, senior vice president of Houston-based Oceaneering, which has about 80 remotely operated vehicles monitoring Gulf wells. In a test offshore Angola last year, Kerin says the ROVs quickly sealed a well in mile-deep seas.

Five years ago, when disaster struck in the Gulf, these robots, lacking high-flow pumps, couldn’t do that. On April 20, 2010, about 50 miles off Louisiana, an explosion on the Deepwater Horizon rig killed 11 workers and triggered the worst oil spill in U.S. history. The blowout preventer, a key safety device that sits atop a well and is designed to seal it in an emergency, failed to activate. For 87 days, until BP’s Macondo well was capped, more than 100 million gallons of oil gushed into the Gulf.

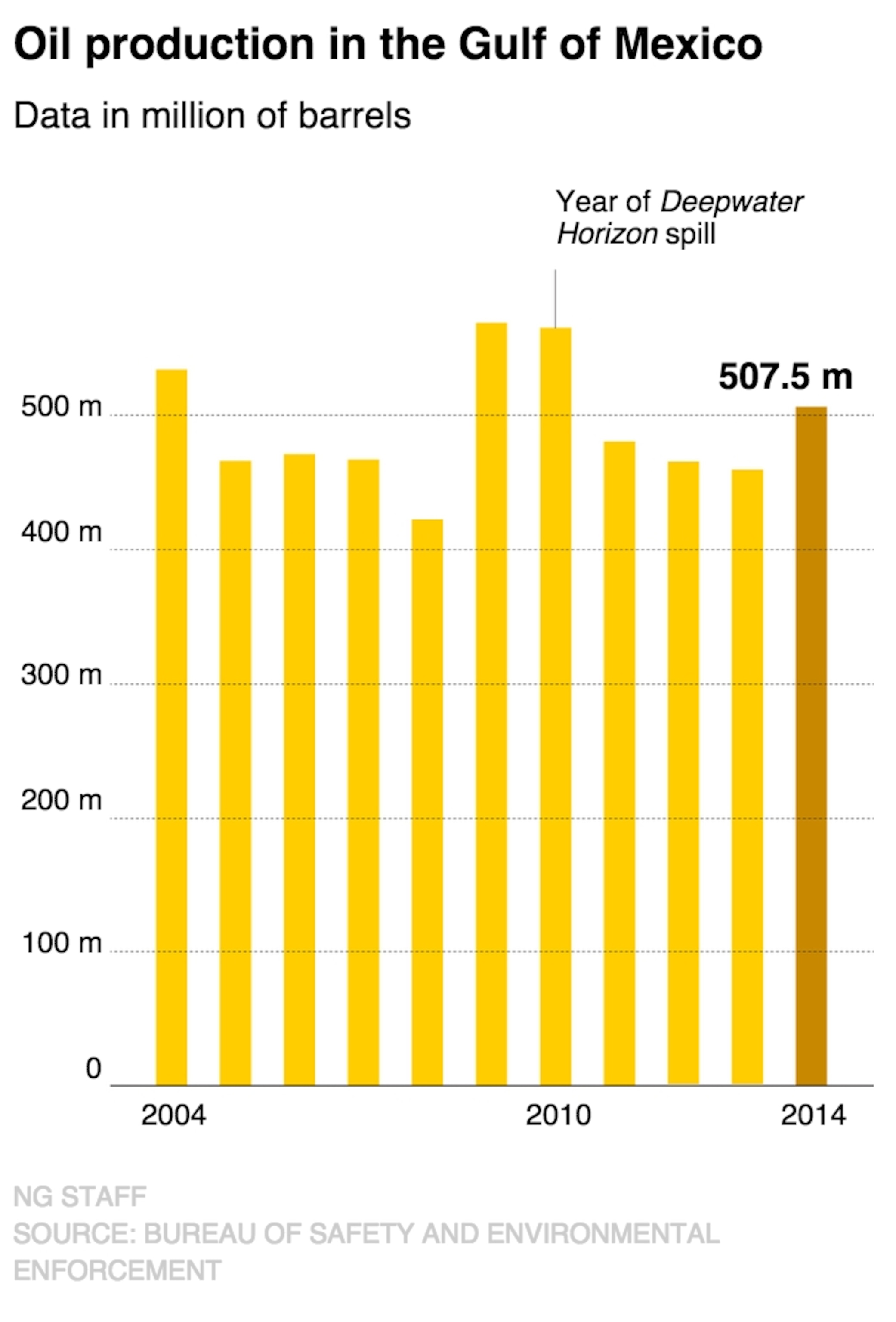

After a six-month U.S. ban on deepwater drilling and a slew of technological and regulatory changes, business is back in the Gulf—with an increasing share of drilling occurring in deep waters at least 500 feet (132 meters) below the surface.

“Can an accident happen again? Of course it can, because we’re going down deeper and deeper,” says Charles Ebinger, an energy expert at the Brookings Institution, a Washington-based think tank. However, he expects future accidents will not be as serious as the 2010 disaster because of recent safety measures.

Last week, the Obama administration proposed new rules for offshore oil and gas rigs that would require more testing, monitoring, and backup equipment for blowout preventers.

BP and other oil companies say deepwater drilling is safer now. Many industry watchers and environmental groups agree, but given the push toward ultradeep Gulf wells drilled a mile or more underwater, they say it’s still not safe enough.

“I don’t have any doubt it’s safer than before, but you can’t eliminate risks in operations like this,” says Michael Bromwich, who led the Interior Department’s newly created agency to regulate the industry after the Gulf spill. “Anytime you go deeper, the technological risks increase.”

Mile-plus Deep Drilling

The blowout preventer on BP’s Macondo well failed to stop oil rushing up from the well, which was drilled 13,362 feet (4,073 meters) into the seabed. When the rig sank two days later, the pipe connecting the rig to the blowout preventer collapsed, according to a ruling last year by Federal Judge Carl Barbier.

BP was declared grossly negligent, with the judge citing the company’s cost-cutting steps. Lesser blame was assigned to Transocean, which owned the rig but leased it to BP, and Halliburton, which did the well’s cement work.

The Macondo well wasn’t unusually deep then or now. In fact in 2009, in another BP field in the Gulf, the Deepwater Horizon rig had drilled in 10,000 feet (3,048 meters) of water and to total depths of about 35,000 feet (10,668 meters).

Most of BP’s current Gulf drilling—by three of its four major rigs: Atlantis, Thunder House, and Na Kik—occurs in water at least a mile deep. Other companies, including Chevron and ExxonMobil, also are drilling deep.

Of the 83 working rigs last year in the Gulf, the Interior Department says 63 operated in deep water—a sharp increase from the 14 rigs that drilled in deep water five years ago.

“The data that we have shows that the rig count in deep water, which is where the real opportunities are, are on the rise,” Abigail Hopper, director of Interior’s Bureau of Ocean Energy Management, told a U.S. House panel in March.

These deep wells are now yielding more oil. BP says it produced 252,000 barrels per day in the Gulf last year, up from 189,000 in 2013. Total Gulf production also rose in 2014, after declining for three straight years following the BP spill.

Plunging oil prices might not curb this uptick in deepwater drilling. Despite falling from about $100 per barrel in September to $50 now, the U.S. government expects the increase to continue through 2016 because of the long time lines of deepwater Gulf projects. Five such projects began in the last three months of 2014 and another 13 are expected in the next two years, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration. The Gulf will account for about 16 percent of total U.S. oil production this year. BP says deepwater wells are expected to generate about half of its operating cash in 2020.

Nevertheless, Kerins, whose company makes undersea robots, says the market is slowing. “Contracts are being canceled,” he says, as the oil industry looks to reduce costs. Federal data indicate the slowdown, though, is occurring in shallow-water projects—not in deep production wells.

Safety Changes Follow BP Spill

Major oil companies banded together after the 2010 spill to create the Marine Well Containment Company and the Helix Well Containment Group, which have a readily deployable system for capping wells and capturing oil. They issued new or revised industry standards for well design, blowout preventers—including the well-sealing robots—and worker training.

“There are dozens of ways we’ve improved safety over the last five years,” says BP spokesperson Geoff Morrell. He notes training with high-tech drilling simulators and 24/7 onshore monitoring of well operations. BP now requires subsea robots that quickly activate blowout preventers in an emergency.

“Shell* monitors its nearly 300 wells and 11 rigs in the Gulf with a team of 18 engineers and other specialists and advanced computer programs that run 180,000 checks a day," says company spokesperson Kimberly Windon.

The Interior Department stepped up oversight of the industry. It dissolved the Minerals Management Agency, which had been collecting leasing revenue from the industry while also regulating it, and instead created separate agencies, including the BOEM and the Bureau of Safety and Environmental Enforcement.

Interior has issued new rules for the casing and cementing of wells, hired more federal inspectors, and mandated safety management systems as well as independent testing of blowout preventers.

A new oil industry group, the Center for Offshore Safety, reported in an audit that participating companies in 2013 reported no fatalities, loss of well control, or oil spills greater than 10,000 gallons.

“People understand the risks and the hazards,” says Center for Offshore Safety Executive Director Charlie Williams. Better training and enhanced standards have made the industry “even safer than before,” he says.

Concerns Linger About Deepwater Drilling

“We’ve heard that story before,” says David Guest, managing attorney in the Florida regional office of the environmental group EarthJustice.

Guest says the industry touted safety changes after the 1969 Union Oil spill near Santa Barbara, California, and the massive 1979 Ixtoc I blowout in the shallow waters of Mexico’s Bay of Campeche.

“It’s inherently risky business,” Guest says of ultradeep drilling, noting the total darkness and extreme high pressures of working a mile or more underwater in the middle of the ocean.

Earlier this month, in an eerie reminder of the Deepwater Horizon blast, an explosion and fire occurred on another rig in the Gulf of Mexico, killing four people and injuring as many as 16 others. Mexico’s state-run oil company, Pemex, which owns the rig, reported no evidence of a major oil spill.

We really can’t say we’ve done everything to prevent this from happening again.Bob Deans, Spokesperson, Natural Resources Defense Council

“We really can’t say we’ve done everything to prevent this from happening again,” says Bob Deans, a spokesperson for the Natural Resources Defense Council and co-author of the 2010 book, “In Deep Water: The Anatomy of a Disaster, the Fate of the Gulf, and Ending Our Oil Addiction.”

Deans says Congress hasn’t passed a single bill to improve industry safety since the Deepwater Horizon spill, and the Obama administration, despite giving Shell preliminary approval to resume Arctic drilling, hasn’t finalized its new blowout preventer rule.

Also, he notes that the oil industry’s new capping stack was tested at 6,900 feet (2,103 meters) underwater even though some drilling occurs at 10,000 feet (3,048 meters). In addition, it would take at least a week for the capping stack to plug a blown-out well, says Marine Well Containment Company CEO Don Armijo.

Deepwater drilling still relies on the same underlying technology and a skilled workforce, says Paul Bommer, who holds the Chevron lectureship in petroleum engineering at the University of Texas at Austin. “It’s still a people business,” Bommer says.

The industry may become complacent again, warns Bromwich, the former U.S. regulator who now runs a crisis-response consulting firm. He worries that lower oil prices will force cost-cutting measures. When budgets are tight, “training is the first thing to go.”

Bromwich sees a “constant stream of technological innovation” yet wonders just how effectively some of these devices—such as the well-sealing robots—would perform in a real emergency.

*Shell is sponsor of National Geographic’s Great Energy Challenge initiative, which explores energy issues. National Geographic maintains autonomy over content. For more, visit The Great Energy Challenge.