Space Rocks Delivered One-Two Punch to Ancient Earth

Scientists link a rare, double impact crater in central Sweden to a 470-million-year-old cataclysm in the asteroid belt.

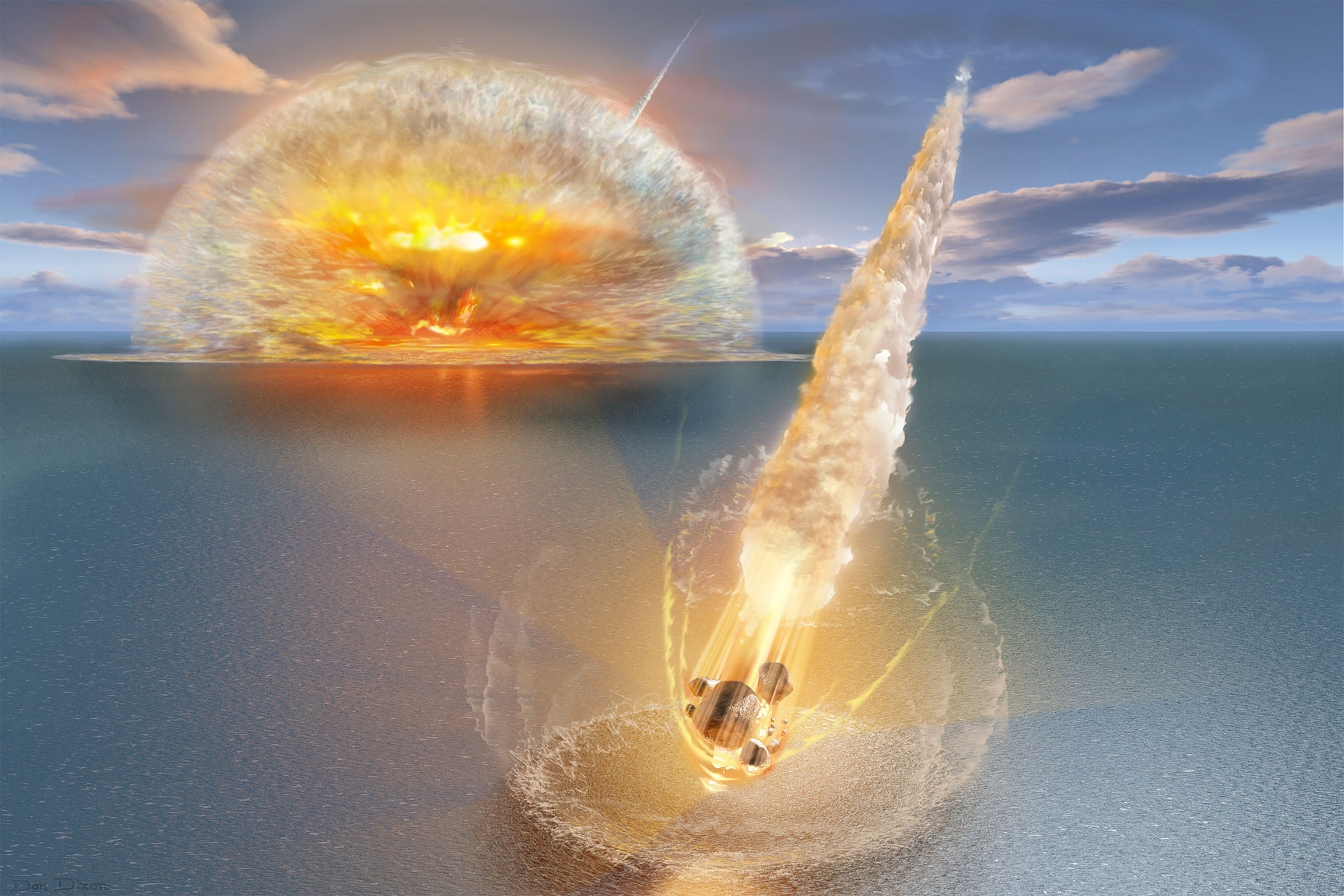

SAN FRANCISCO — Around 470 million years ago, what is now central Sweden was covered in a shallow, ancient sea inhabited by tiny, plankton-like organisms. The placid scene would soon be scarred by one of the largest cataclysms in the last billion years, scientists reported Monday.

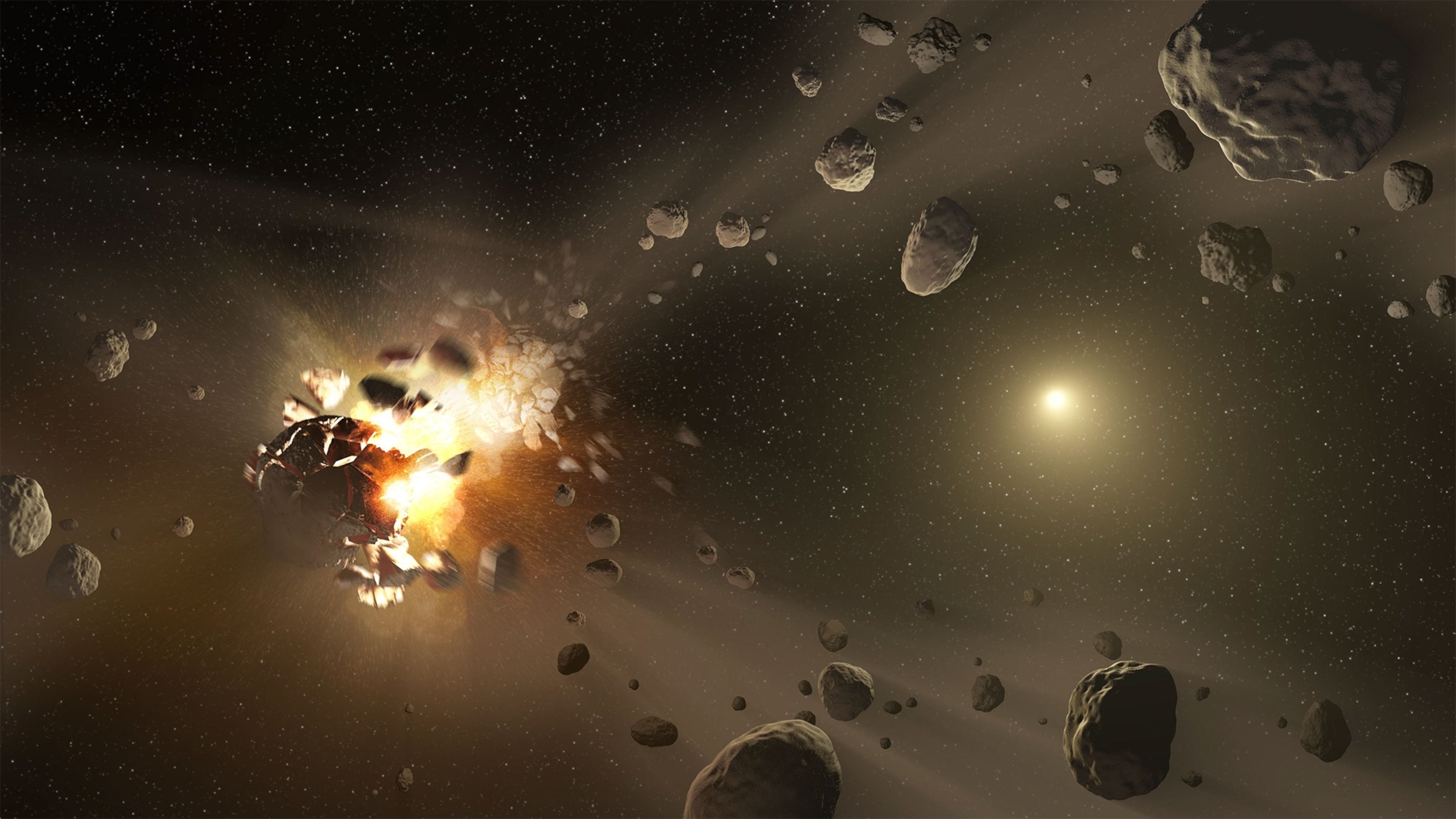

That's because far away, trouble was brewing. In the main asteroid belt, between Mars and Jupiter, two space rocks were about to collide. When they slammed together, the collision shattered a 200-kilometer-wide asteroid, sending fragments ricocheting through space—some of which headed right for planet Earth.

As they traveled through the inner solar system, a portion of these pulverized bits and pieces re-congealed, forming what's known as a rubble pile asteroid—a type of space object that is exactly what it sounds like. But this rocky swarm wasn't like most of the others: It had a small, orbiting companion.

And when that twosome finally plowed into the ancient Swedish sea after a 12-million-year journey, it left a distinctive double crater. Or rather, a double crater that would have been distinctive had the smaller of the two punches not remained hidden until just a few years ago.

"We are quite convinced that the two craters were formed at the same time," says Erik Sturkell of the University of Gothenburg, who presented the story Monday at the American Geophysical Union's annual meeting.

Double Whammy

Binary craters aren't exceptionally common on Earth, even though roughly 15 percent of asteroids in Earth-crossing orbits are thought to have a companion in tow. That’s because “getting two distinct nearby craters that are well dated has been hard to accomplish," says Bill Bottke of the Southwest Research Institute.

Today, these two 458-million-year-old craters—Lockne and Målingen—are set amidst forests and farmlands. Lockne, the larger of the two, is about 7.5 kilometers across and was created as the rubble pile asteroid collided with Earth. About 16 kilometers away is Målingen, which is just 0.7 kilometers across and made by the smaller companion.

Scientists aren't sure precisely how big the two asteroids were, but they estimate the bigger one was at least 600 meters across, and the smaller was at least 150 meters across. Rubble pile asteroids create craters that are a bit different than the scars left behind by dense, intact impactors.

"The fragments separate but maintain their trajectory," Sturkell explains. "The effect on the target area can be compared to that of a shotgun blast rather than a single rifle bullet—a shallow, widespread, but still coherent crater."

Cataclysmic Breakup

The fossilized remains of those hapless, plankton-like organisms helped the team determine how long ago planet Earth had gotten punched.

But, how did scientists link these craters with that 470-million-year-old cataclysm?

For starters, the asteroids that gouged these double pockmarks into Earth are a particular type of space rock called an L chondrite—something that is rich in olivine and relatively iron-poor. Sprinkled all over the planet are craters of similar ages, made from the same type of asteroid...and there are too many similarly aged craters, with similar fingerprints, to be explained by normal cratering rates.

In addition, more than 100 fossilized meteorites have been uncovered from Sweden, China, and Russia. These small, preserved fragments arrived on Earth around the same time, and all except one are L chondrites. What's more, the fragments bear the signature of an ancient collision that occurred about 470 million years ago—before they barreled into Earth.

The only way that pattern could emerge is if a mishap of cosmic proportions destroyed a parent space rock and sent shrapnel flying through the solar system.

"It probably went through a supercatastrophic disruption event," Bottke says, noting that, in addition to the cataclysmic breakup, research suggests the parent asteroid happened to be in a spot where gravitational nudges from Jupiter could efficiently send fragments flying toward Earth.

"A lot of this material was able to get to Earth very quickly," he says.

But not all the fragments left their home: Today, the shards from that collision that still live in the main belt are known as the Gefion family. "There is a lot of cool stuff related to this particular event," Bottke says. "The question is whether this event had other implications, say for life on Earth."

Follow Nadia Drake on Twitter and her blog on National Geographic’s Phenomena network.