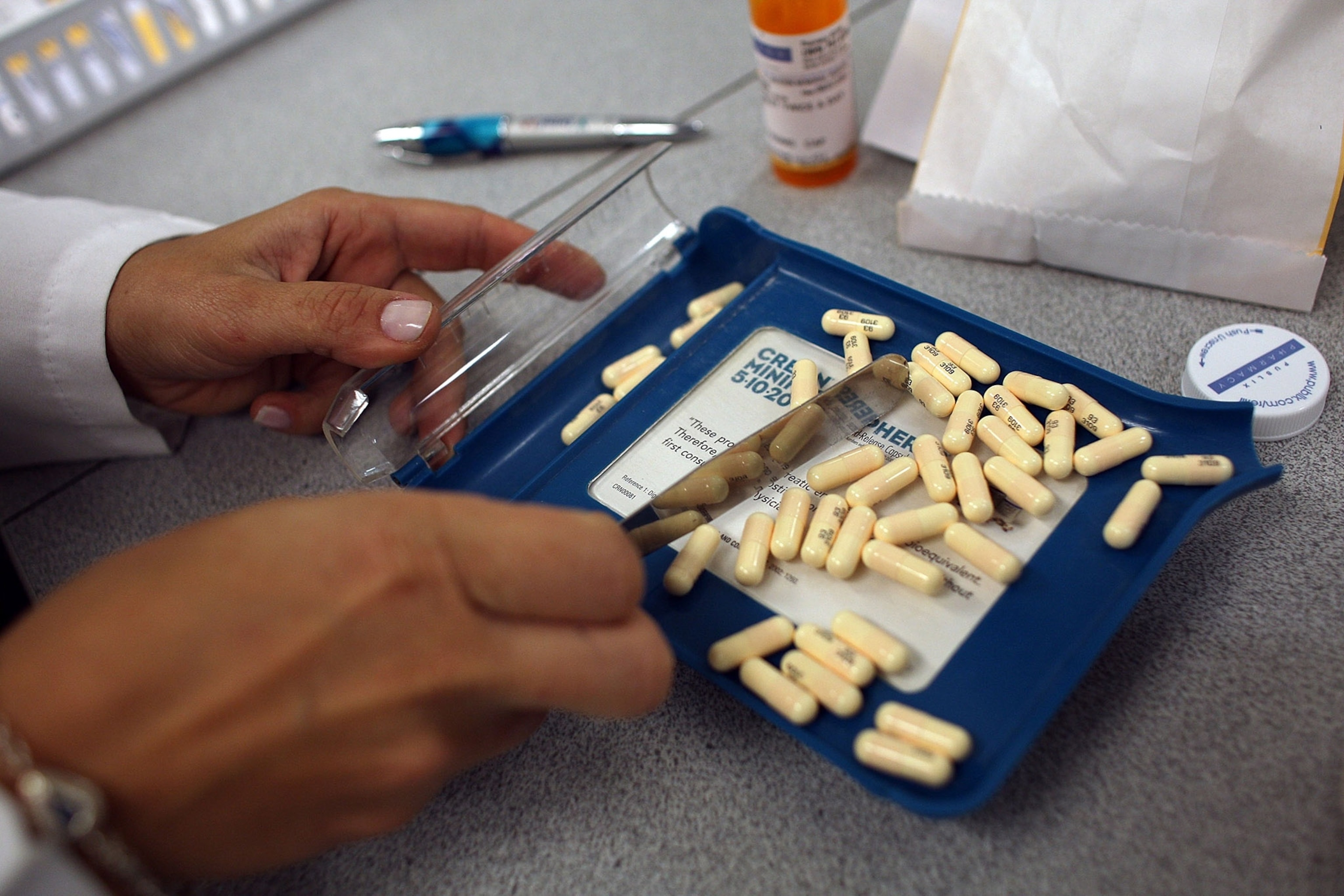

A Third of People Given Antibiotics Don't Need Them

Flu, STIs, and other ailments are being unnecessarily treated with the bacteria-fighting drugs—and patient demand is partly to blame.

It’s a stunning statistic.

Three-fourths of emergency room patients who are given antibiotics for a possible sexually transmitted infection don’t actually need them—because they don’t have the infection doctors think they have.

That finding, presented at a conference last summer by researchers from the St. John Hospital and Medical Center in Detroit, is one of several recent reports that say antibiotics are being used far more than necessary in medicine.

(Alligator blood may lead to powerful new antibiotics)

In fact, a third of antibiotic prescriptions written in medical offices are unnecessary, given for things such as viral infections that antibiotics can’t cure, according to a May report by physicians from around the country and from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, brought together by the Pew Charitable Trusts.

The same group found that half of the antibiotics prescribed to treat very common problems such as sore throats and ear infections shouldn’t be used because they’re “broad spectrum”—capable of killing many organisms and thus more likely than infection-specific “narrow spectrum” drugs to stimulate antibiotic resistance.

This, and many more pieces of research over the years, indicates a stubborn problem that no one is quite sure how to solve. While a slew of health organizations and national governments are all ringing the alarm about antibiotic resistance, the medical misuse and overuse that fuel its development just keep happening.

When More Isn’t Better

Medical use of antibiotics isn’t the only contributor to resistance, which, according to one estimate, kills 700,000 people around the world each year. Antibiotic use in livestock—by sheer tonnage far outweighing what goes into humans—plays a role as well. But since medical prescriptions are written by doctors, it seems fair to ask: Why can’t they stop?

“That is the million-dollar question,” says Lauri Hicks, a physician who leads the CDC’s Office of Antibiotic Stewardship. “This is really about behavior change, and behavior change is notoriously difficult. We have a public perception, even in the clinical world, that when it comes to antibiotics, more is better.”

That’s true in ER and doctor’s-office encounters and, according to newer research, seems to be true in hospitals as well. Other CDC researchers just reported that antibiotic use in U.S. hospitals didn’t change from 2006 to 2012, despite pressure to use the drugs less. In fact, use of last-resort antibiotics—those that need the most protection from resistance—went up.

There’s no shortage of information telling doctors that this is a bad idea. World Antibiotic Awareness Week recently highlighted the problem of resistance and recruited medical and health-care organizations to make public commitments to solve it. The CDC has been running its “Get Smart About Antibiotics” program since the 1990s.

Yet inappropriate prescribing has barely budged.

The Yelp Effect

In a just-published commentary in the journal JAMA Internal Medicine, two physicians from Harvard Medical School and its affiliated hospitals sound exasperated that this still goes on.

“The overuse of antibiotics is not a knowledge problem or a diagnostic problem,” Ateev Mahotra and Jeffrey Linder write. “It is a psychological problem. More specifically, there are strong factors pushing the physician toward prescribing an antibiotic and weaker factors pushing against.”

Hicks says the CDC’s studies of the problem persistently find several barriers. “There is a perception that the safer approach is to treat” even if a diagnosis is not pinned down, she says; and physicians may be worried that if they don’t write a prescription and a patient becomes seriously ill, a lawsuit will follow.

David Hyun, a pediatric infectious disease specialist who works in the Pew Trusts’ antibiotics project, adds that some physicians worry their health-care organizations will scold them if they take too long seeing patients—and explaining why an antibiotic is not needed almost always takes longer than writing a prescription.

But both experts agree that one factor influences antibiotic prescribing more than any other. “The overriding theme, in all the research that has been done, is patient satisfaction,” Hicks says.

Patients who believe they have an illness go to the doctor expecting a fix. They imagine that fix will be an antibiotic. When an antibiotic isn’t forthcoming, they feel the visit didn’t go as planned.

“There are basic social interactions between providers and patients,” Hicks says. “Most doctors want their patients to feel satisfied at the end of the visit.”

That realization turns the medical encounter around; instead of the doctor being the person with the power, it’s the patient, wielding the moral suasion of disappointment. While that’s probably always been the case, research now shows that another factor is increasing the pressure. Call it the Yelp effect.

“When I practiced at an academic children’s hospital, my outpatient[s] … were given surveys to score their experience with the visit and with myself as a provider,” Hyun says. “And those scores were taken into account internally when my employer did my performance review.”

With the rise of stand-alone medical offices—drop-in practices where someone can go without advance warning or a prior relationship—that pressure for good reviews has increased even more. “One of the most common phrases we hear in interviews is, ‘If I don’t give the antibiotic, they will go across the street to the urgent-care center and get their antibiotics there,’” Hyun said. “There’s an economic motivation. Physicians want to retain their patients.”

The Downsides of Antibiotics

Are there solutions? Hyun found that when he was able to spend time with his child patients and their parents, explaining why antibiotics weren’t the right approach, the parents were less likely to insist on a prescription. The CDC backs medical offices putting up posters and “commitment letters” that emphasize wanting to be conservative.

The agency is also asking physicians to stress to patients that antibiotics have downsides—not just the remote threat of antibiotic resistance but also the immediate risk of developing life-threatening C. difficile infections when antibiotics kill off bacteria in the gut.

“When we talk to patients about adverse events and antibiotics, they’re shocked; they didn’t know those existed and were upset providers had not discussed them,” Hicks says. “We have to get better at communicating the benefits and also the risks of antibiotics: that these are miracle drugs, but we should also be much more cautious using them.”